For several days, Ernesto Guevara, Che’s son, had been leading a group of eight on a motorcycle tour around Cuba. The escapade was filled with the island’s usual mild chaos and misadventures, which Ernesto had tackled with dry humor. “Some of the potholes out here have names,” he said of the decaying country roads. “They’ve been here for so long people are fond of them. They’re like pets.” But he grew quiet as we began to explore Santa Clara, the provincial city that encapsulates Che’s short, operatic life and helped turn him into one of the most recognizable—and yet, little-known—figures of the modern era.

As every Cuban school kid knows, Santa Clara was the site of Che’s greatest victory during the Cuban revolutionary war of 1956-9. It was then the crossroads of the island’s transportation system and a key strategic goal in the armed rebellion led by Fidel Castro against the U.S.-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista. The Argentine-born Che (whose real name was Ernesto; Che is Argentine slang for “pal” or “buddy”) had joined the uprising as a medic, but rose through the ranks to become Fidel’s most trusted field commander. In the last days of December 1958, Che led 340-odd guerrillas—mostly men, but also a few women, including Che’s future wife—from the wild Escambray Mountains into the flat, exposed sugar country of central Cuba, to take on some 3,500 of Batista’s soldiers in Santa Clara.

Pausing at the city’s revered battle sites, we spotted bullet holes on the walls of a hotel in the plaza and tried to imagine the house-to-house fighting, when residents made Molotov cocktails for the feisty rebels to use against army tanks and invited them into their homes to help outwit an enemy force ten times their number. On December 29, Che used a tractor to tear up rail tracks and overturn an armored military train, seizing weapons and dozens of prisoners. The demoralized army abandoned Santa Clara to the guerrillas—and a turning point in the revolt. When news of the defeat reached Havana, Batista made plans to escape. Early on January 1, 1959, he left a New Year’s Eve party to climb into a DC-4 aircraft with a handful of his cronies and fled the island for the Dominican Republic.

Today, The “Tren Blindado,” or Armored Train, is preserved as a monument to the revolution, complete with a museum inside the carriages and shops across the street selling Che T-shirts. Ernesto Jr. slipped past, trying to avoid attention. Now age 54, he is a little portly and has silver flecks in his hair, but he is without doubt his father’s son; in fact, he looks, one imagines, much as Che himself would have looked had he lived to middle age.* He remains as awed as any other Cuban at his father’s victory against the dictator’s massive war machine; most of Che’s men were no older than college kids, and many were in their teens. “They were all crazy!” Ernesto said. “They were just a bunch of young guys who wanted to get rid of Batista at any cost.”

Next we drove to Santa Clara’s other great attraction: the Che Guevara Mausoleum, where Che’s remains are interred. The setting has a vaguely Soviet feel. Looming over the blocklike concrete structures is an enormous bronze statue of Che, instantly recognizable in his loose-fitting fatigues, beret and scrappy beard. He is holding a rifle and gazing implacably into the future—an ever-youthful, ever-handsome image that is echoed on propaganda posters in every corner of Cuba, usually accompanied by Che’s revolutionary slogan, ¡Hasta La Victoria Siempre! “Always Towards Victory!”

After the group parked their Harleys, Ernesto led us past the crowd of tourists and through a side entrance. A flustered attendant, clearly dazzled by Ernesto’s celebrity, showed us into a salon to sit on brown vinyl sofas beneath a painting of Che on horseback. The group under Ernesto’s wing—four German bikers, one Swede, an English couple and one American, a retired schoolteacher from Connecticut, as well as myself—were all brought sweet Cuban coffee and given a crisp political briefing: “This memorial was built as a tribute from the people of Santa Clara to the man who set them free,” the attendant said. “The mausoleum opened in 1997, the 30th anniversary of Che’s murder,” she said, and added that the date of his last battle, October 8, is still celebrated every year in Cuba as “The Day of the Heroic Guerrilla.”

She asked us to sign the guest book. I penned a note in Spanish for the whole Harley group, signing it La Brigada Internacional, “The International Brigade,” a joking reference to leftist foreign volunteers in the Spanish Civil War. Ernesto, however, had grown increasingly somber. When it came time to enter the mausoleum itself, he made his apologies. “I’ll wait for you outside,” he muttered. “Es demasiado fuerte. It’s too charged.”

The bikers entered the dark, temperature-controlled shrine, where an eternal flame was flickering over Che’s tomb. One of the walls was taken up by the crypts of Che’s fellow guerrillas who died with him in Bolivia, each one remembered with a red carnation, replaced daily. A reverent silence fell over the group as the attendant told the gloomy saga of the “three dozen compañeros” who fought alongside one another in the cold, faraway Andes. “Che could not rest while there was injustice still in the world,” she said—a platitude, maybe, but there was some truth in it.

Though Cuba is celebrated for its vintage cars, at Chacón 162, a bar in Old Havana, the vibe is all about old motorcycles, including a vintage Harley donated by Ernesto. (Lisette Poole)

We filed into an attached museum, which told the story of Che’s extraordinary life, starting with his childhood in the Argentine city of Rosario in the 1940s and his move as a medical student with matinee idol good looks to Buenos Aires. On display were his favorite books, including Don Quixote; his bombilla, the bulb-shaped pot from which he drank his Argentine tea, maté; and an asthma inhaler. There were also images from Mexico City in 1955, where the peripatetic Che met Fidel, an idealistic young lawyer-turned-revolutionary, at a dinner party. The two had opposite personalities—Che a soulful, poetic introvert, Fidel a manically garrulous extrovert—but possessed the same revolutionary zeal. Che signed on as medic for Fidel’s mad project of “invading” Cuba to overthrow Batista. On December 2, 1956, he, Fidel and 80 armed men landed on the island secretly by boat—a near-disastrous experience that Che later described as “less an invasion than a shipwreck.” And yet, within 25 months, the odd couple were in control of Cuba, with Che given the job of overseeing the execution of Batista’s most vicious thugs.

Alongside the images of Che the conquering warrior were startling snapshots from his lesser-known existence in the 1960s—as a family man in Havana. Soon after the 1959 victory, he divorced his first wife, a Peruvian activist named Hilda Gadea, to marry his wartime sweetheart, Aleida March. The couple had four children: Aleida (who was given the Russian nickname Alyusha), Camilo, Celia and Ernesto. The last photograph, blown up to poster size, was the most startling and intimate. It showed Che cradling a month-old baby with a bottle of milk as one of his daughters looks on. The official saw me staring. “That’s Ernestito,” she said quietly: “Little Ernest.”

* * *

The vision of Che the revolutionary is so familiar—his raffish, beret-clad visage reproduced on coffee cups and college dorm silk-screen prints around the world—you forget he had any other existence. “The most striking thing about Che is that he had a private life at all,” says Jon Lee Anderson, author of Che: A Revolutionary Life. Che would write tender poetry for his wife, and when he departed for the Congo in 1965, left tape recordings of his favorite romantic verse, including Pablo Neruda’s Goodbye: Twenty Love Poems. He also left a letter for his four children to be opened and read only in the case of his death.

Such domestic details have no part in the official Che iconography, Anderson adds, because propagandists thought such tenderness would undermine his reputation as a selfless revolutionary martyr. “Che could do no wrong,” he says. “By the 1990s, he was a cardboard cutout without any flesh and blood.”

That began to change with the publication in 1995 of The Motorcycle Diaries, a travel memoir Che had written when he was an unknown 23-year-old, about his epic 1952 jaunt with a friend from Buenos Aires along the spine of the Andes, in part on a rusty, wheezing motorbike they dubbed La Poderosa (“The Powerful One”). The bike actually breathed its last gasp in Chilean Patagonia, forcing the pair to hitchhike most of the way. But the disarmingly frank opus also revealed Che’s inner journey from a shy, lovelorn and self-absorbed middle-class student to a man who passionately sympathized with oppressed people all over Latin America. It became an international best seller, in part because his youthful, Kerouac-esque bravura prefigures his dashing, man-of-action future. Its reach increased exponentially in 2004 when a film version was released starring the doe-eyed Gael García Bernal, fixing the vision of Che and his two-wheeled adventures in pop culture for the 21st century. So when I heard that Che’s youngest son was an avid Harley-Davidson fan leading “Poderosa Tours” around Cuba, the prospect was compelling, to say the least.

Michael Laverty, whose company Havana Strategies has been running high-end educational trips from the United States to the island for over a decade, suggested that I take my time asking Ernesto about his notorious lineage: “He doesn’t like all the commercial stuff around his father. Most of the time, he can go into a bar and not be recognized.”

Each of Che’s four children with Aleida have dealt with their famous lineage in different ways. Alyusha, now 58, became a doctor. In the 1980s, she volunteered for duty when Cubans were militarily involved in Nicaragua and Angola, and since then she has worked around the developing world on Cuban medical aid projects. The second daughter, 56-year-old Celia, is a marine biologist and now works at the Havana Seaquarium specializing in seals and porpoises.* She keeps her distance from the Che connection. Che’s sons, Camilo, age 57, and Ernesto, faced more of a psychological burden, according to Anderson: “I always felt that Che was such a massively iconic figure, it must be very difficult to be his son—to look like him and not be him.” Camilo practiced as a lawyer and (like his father) dabbled in photography; he now helps manage the Che Guevara Study Center opposite their family home in Havana. But it is Ernesto whose filial link has now become most explicit. What that meant I hoped to discover after I met up with the biker tour group in the lobby of the Melia, a stark state-run hotel that looms over the Malecón, Havana’s seafront promenade.

Hell’s Angels they were not. Like many Harley fans today, they were older, affluent and a little stout. Soon we were all corralled by Ernesto’s biking partner and best friend, Camilo Sánchez, a wiry figure with a silver goatee whose father had been killed in Bolivia with Che. The trip’s organizer was a tiny, animated Cuban woman named Ina, who kept los chicos, the boys, on schedule. Ernesto called her mi comandante, a reference to the top rank in Fidel’s rebel army.

Ernesto, we soon found, was not entirely anonymous. As we stood by the Harleys in the hotel driveway (sometimes I rode with Ernesto, other times I followed the group in a car), he was stopped by some older Cubans who asked to take a photo with him. Ernesto amiably posed with them. “There’s no harm in it,” he shrugged. “It’s like Havana Hollywood!”

German bikers ready to hit the road. Tony Perrottet

As Ernesto climbed onto his black Harley, he put on a shiny new German Army-style silver safety helmet, provoking teasing from his friends. “Looks like you made friends with Hitler!” Ina laughed. “You terrorist!” Before setting off, Ina gave the bikers a briefing on the island roads. “You have to look out for cows, goats, dogs, cats and drunken Cuban people!” she warned. “Pay attention! We forgot to bring the body bags!”

Within an hour, the motorized traffic of Havana had given way to push bikes and mule carts. While Havana is no longer “stuck in the 1950s,” as the cliché about Cuba goes, the countryside has an undeniably retro air: Weather-beaten men in straw cowboy hats and women in snow-white frocks stopped to stare as we roared through crumbling villages under the beating tropical sun. At roadside rest stops for guava juice or fresh coconuts, the patter betrayed little reverence for Che’s illustrious bloodline. Ina had addressed Ernesto as gordito, “little fatty,” a term of endearment. “Ernestito is not as tall as Che was,” she explained. “He’s got his father’s face and his mother’s body. She was a bit short and chubby, even when she was young. You see the photos!” Far from taking offense, Ernesto laughed indulgently: “I used to be handsome, a real Brad Pitt-ito!”

Having written a book about the Cuban Revolution, I was a little star-struck myself and lapped up shreds of Guevara family gossip. Ernesto talked about his efforts to get his mother to retire as director of the Che Study Center: “She’s 85 years old and still working. I say to her, ‘Enough already!’ But that’s what happens with the generation of the revolution. They keep working until they literally can’t get out of bed. They think it’s a mission.” There were stray references to his father, even about his romantic life. “The whole world wishes that Che had hundreds of novias, girlfriends,” he said. “In reality, he only had two, the poor guy: his two wives.” He then dropped his voice to offer the opposite view. Che was always surrounded by female admirers, he noted; in 1959, dozens of Cuban mothers and their daughters lined up to meet him every day, forcing him to barricade his office door to keep them at a distance. One famous photo shows a trio of French female journalists hovering around Che, all clearly enraptured. “When Che first went to Africa, the party officials called up Fidel and said, ‘Why did you send us this womanizer?’” he laughs.

Yet Ernesto seemed uncomfortable talking seriously about his family. He stuck to generalities, and always referred to his father in the third person, “Che.” Then, after dinner on our first night in Trinidad, an exquisitely intact Spanish colonial town 200 miles southeast of Havana, we repaired to a nearby open-air bar where two of Ernesto’s musician friends were playing jazz. Ernesto immediately relaxed. Soon he was playing air guitar and scatting to his favorite songs, while he and Camilo knocked back glasses of aged rum and chomped cigars.

Ernesto Guevara jamming at a bar in Trinidad. Tony Perrottet

Ernesto opened up about his singular childhood, which was shaped by Cold War politics. After the 1959 victory, Che traveled the world constantly, making lengthy trips to the USSR, Africa and Asia, and was away at a leftist conference in Algeria when Ernesto was born in 1965. At home in Havana, the austere and disciplined Che worked long hours, six days a week, first as the head of the National Bank and then as minister for industry. On his day off, he volunteered as a laborer in the cane fields, a nod to Mao’s China. The only time for his children was late Sunday afternoons. But the absences were taken to another level in 1965, when Che tired of his office job and decided to return to the field as a guerrilla. Ernesto was 6 weeks old when Che vanished to the Congo. Aleida wrote offering to join him there; he shot back angrily that she should not play on his emotions: “Love me passionately, but with understanding; my truth is laid out and nothing but death will stop me.” After the uprising in the Congo failed, Che slipped back into Cuba. Ernesto was just an infant. His mother took him to meet Che in a clandestine guerrilla training camp.

The most surreal family gathering came in mid-1966, when Che had assumed the disguise of “Ramón,” a bald, aging Uruguayan businessman, so he could travel the world incognito, under the nose of the CIA. He was forced to maintain this fake identity when he met the four children in a safe house in Havana. The scene was “especially painful,” Aleida later wrote: Alyusha, then 6, saw how fondly the “family friend,” Ramón, looked at her. “Mommy,” she said, “that man is in love with me!” Che soon left for the Andes. “There are days when I feel so homesick,” he wrote to Aleida, lamenting “how little I have taken from life in the personal sense.”

The letter he left for his children to read after his death is more political than paternal. “Grow up to be good revolutionaries,” he writes. “Remember that the Revolution is what is important and that each one of us, on our own, is worthless.”

Advance word of Che’s execution in Bolivia was passed by Cuban intelligence services to Fidel, who called Aleida back from a work stint in the countryside to give her the grim news personally. Ernesto was only 2 at the time, Alyusha 8, Camilo 4 and Celia 3. A million Cubans gathered for an all-night vigil for Che in Havana’s Plaza of the Revolution. The family watched it on television, lacking the strength to appear in person. Haunting photographs of the dead Che lying Christ-like on a concrete washbasin in the hospital laundry of the village where he was killed also circulated. Devotion to Che was cultlike. In Italy, a left-wing businessman began making silk-screen prints of Che in his starred beret, from a photo taken by Alberto Korda at a rally in 1960. Across Cuba, heroic posters proliferated. “Growing up, I saw my father’s face everywhere,” Ernesto recalls. “I don’t remember a time when I wasn’t surrounded by photos of him. It wasn’t like I had to ask, ‘Who is this?’ Che was always there, all around me.”

Supporters rallied around the children, with many of Che’s family and friends from Argentina moving to Havana. They were also looked after by “Uncle” Fidel. In some ways, growing up within a Socialist system meant they were treated like other kids. “We went to the same schools as everyone else, we had contact with everyone,” Ernesto insists. In the 1970s, with the Sovietization of Cuba, Ernesto attended the Escuela Ciudad Libertad (“Liberty City School”) and the Lenin Vocational School. Nonetheless, he was something of a celebrity. “Teachers said we looked exactly the same, Che and I,” he admitted later to me. “It was a bit complicated. I had a different experience to the other school kids, for good and for ill,” he adds. “I was a bit isolated. If I was good, one group hated me, if I was bad, another group hated me.”

“All of the [Guevara] children had a hard time,” Anderson says. “They struggled to escape from their father’s shadow.” It’s a situation that Che himself had anticipated in an eerily prescient short story titled “The Stone,” which he had written in the Congo in 1965 after learning about his mother’s death. In it, Che ponders his mortality and even imagines his corpse being displayed, as it was in Bolivia. He also predicts that his sons would feel a “sense of rebellion” against his posthumous fame: “I, as my son, would feel vexed and betrayed by this memory of I, the father, being rubbed in my face all the time.”

* * *

Like many Habaneros in the golden age of Soviet support, when sugar subsidies propped up Cuba’s economy, Ernesto traveled to Moscow for college. “I arrived in winter,” he recalls of his time there in the 1980s. “The cold was punishing! When I first saw snow, I was like: What the hell? Some days it was minus 40 degrees, and the darkness seemed to last for three or four months. But I liked the idiosyncrasy of Moscow. The city was full of Cubans, and we got together for fiestas.”

Ernesto studied law but never used his degree. Returning to Cuba at age 25, he joined the armed forces with his childhood friend Camilo Sánchez, and after training as commandos, the pair went to fight in Angola in 1987, then Nicaragua. In the mid-1990s, while in his 30s, Ernesto transferred to the security unit assigned to protect Cuban officials. The sanctification of Che, already underway, went into an even higher gear following the collapse of the Soviet Union, which plunged Cuba into an economic crisis—food and fuel rationing, malnutrition, and increasing isolation due to the ongoing U.S. trade embargo. Government propaganda spotlighted Che’s self-sacrifice. Meanwhile, Ernesto tried to live a normal life. He married and had a daughter and a son, also named Ernesto, who is now 22 and the only male of Che and Aleida’s ten grandchildren. In 2002, Ernesto married his second wife, the Greek-born Maria Elena Giokas, with whom he has two daughters, ages 15 and 5.

For Ernesto to be leading motorcycle tours named after his father’s bike raises questions a Freudian might have a field day with. But he rejects any psychological explanation as simplistic. “In truth, my love of bikes was not from a need for connection with Che,” he says. “It just seemed natural. All the kids in Havana were doing it. I also went into the commandos,” he adds, “but it wasn’t because my papa was a guerrilla leader. I went to Angola out of a sense of duty, like any young man in Cuba would have.”

Ernesto got his first Harley as a teen, he says—naturally, at the same time as his sidekick Camilo. They sped around Havana even before they had licenses, and became expert at repairing the machines. The Harley connection is not as eccentric as one might think in the shadow of U.S.-Cuban tensions, Ernesto points out. Before the revolution, every police officer in Cuba rode a Harley, which created a reservoir of spare parts.

Ernesto on his Harley. Tony Perrottet

He and Camilo had longed dreamed of leading bike tours, but getting up-to-date Harleys seemed fanciful given the trade embargo. Then, in 2011, the Cuban government encouraged limited entrepreneurship to stimulate the moribund Socialist economy. By 2015, the future seemed auspicious: President Obama normalized U.S.-Cuban diplomatic relations and eased travel restrictions, bringing a flood of U.S. visitors. With funding from a friend and investor in Argentina, Ernesto arranged for a dozen shiny new Harleys to be shipped from the U.S. factory to Cuba via Panama. Poderosa Tours was a hit, and Ernesto now leads up to 15 tours a year. Even the tightening of the embargo by President Trump in 2019 has made little dent in their popularity, since Americans are still able to get travel visas to Cuba through a dozen different categories.

* * *

We proceeded into the Escambray Mountains on the south coast, the city of Santa Clara, and finally the beach-fringed island of Cayo Santa Maria on the north. This last was the most relaxing stretch for biking. The cay is reached by the best road in Cuba, a meticulously engineered causeway that runs arrow-straight for 30 miles across 54 bridges spanning islets and reefs. Potholes are rare, so the bikers could open up the throttles.

Soon we were rumbling back into Havana, where I had one final mission: to meet Ernesto’s older brother Camilo in the former Guevara family residence. Most of its rooms now serve as offices for the Che Guevara Study Center, built across the street in 2002. (I had asked Cuban officials to meet Che’s widow, Aleida March, but got nowhere; a shy and private woman, she has always stayed out of the limelight.) I had read that Che’s small study is preserved in the old house as a shrine, and is still filled with his annotated books and with souvenirs from his international travels, including a bronze statue of “the New Soviet Man”—all exactly as they had been the day he left for Bolivia in 1966.

I took a cab to Nuevo Vedado, an upscale suburb, and entered the former Guevara residence, an Art Deco structure painted a cheerful blue and shaded by bougainvillea, with geometric colored windows. Wearing his long hair tied back in a ponytail, loose cotton trousers, leather sandals and an arty silver thumb ring, Camilo resembled a Hollywood producer on vacation. We sat down next to a bust of Che and chatted about recent events, particularly the tightening of the U.S. trade embargo and the confusing restrictions on travel from Americans.

Camilo was more outspoken than Ernesto had been. “We are entirely unsurprised,” he declared. “It’s the same imperial American approach. There is no forgiveness for Cuba! The idea that one little island can stand up to the empire, to resist the waves of U.S. influence crashing over Latin America, cannot be pardoned.” After an hour or so of such haranguing, he apologized that the study center was closed for renovations due to a 2018 flood. When I asked if I could go upstairs and peek into Che’s study, Camilo froze: “Oh, no, you need proper credentials for that.” He said I would have to return to New York, secure a journalist’s visa and a Cuban press pass.

The study seemed harder to get into than the Vatican. Still, a month later, I dutifully returned with expensive visa and credentials in hand. This time, Camilo was happy to show me around the center, whose mix of concrete and wood gives it a vaguely Pacific Northwest air. The space was currently being used as a children’s day care facility, but barring more natural disasters, in 2020 it will display unseen family artifacts, photos and home movies. It will also house Che’s personal archive, including such treasures as the typed manuscript of The Motorcycle Diaries and a copy of his original war diary from Bolivia, which was smuggled out of the Andes on microfilm in 1967. The center continues to produce Che texts with an Australian publisher, Ocean Books. But it remains wary of outside researchers. “Some historians set out to deliberately denigrate Che’s personality,” Camilo said. “They are fantasists! They come in here looking for documents that don’t exist. But history is not a chunk of meat that you can grind up and turn into chorizo!”

When I asked him about Che’s legacy, Camilo launched into a speech whose passionate socialism and critique of unbridled capitalism would have impressed Fidel. “Che’s life gives us hope,” he said. “It was an act of solidarity with his fellow human beings. People have forgotten today that to be human is to be part of the human race. We’re not elephants, tigers or lions that can face the world alone. We need to work collectively to survive. The planet today is being destroyed. It’s not volcanoes or earthquakes that are doing it. We are doing it ourselves! The world can be a better place. And human beings have to fight for that!” Consumerism is part of the problem, he said. “Life has to have some meaning. What is the point of spending your days on an enormous sofa, in an enormous house, surrounded by televisions? You’re going to die anyway! In the end, what did you leave? People are losing the capacity to change. It’s a lack of imagination.”

Finally, I asked Camilo to show me the shrine I had set my heart on—Che’s study. His face froze again. “It will not happen.” he said. “It’s locked with three keys.”

I was taken aback. The visa and press credentials were not going to help: The resistance to me seeing it ran deeper.

But perhaps that’s as it should be, I suddenly realized. Their father had been for so long the world’s collective property—his life poked and prodded, his every written word pored over, his mausoleum in Santa Clara a tourist attraction visited daily by busloads of people—that the family might want to keep one place private, just for themselves.

Sensing my disappointment, Camilo led me into the courtyard and pulled back a plastic drop sheet to reveal Che’s 1960 Chevrolet Impala. The sleek, emerald green vehicle, with the E and O missing from the silver-lettered brand name across the hood, exuded historic charm. Next to it was another relic: a rickety-looking, military-gray motorbike—the replica of La Poderosa used in The Motorcycle Diaries film. The producers had given it to Che’s old traveling companion, Alberto Granado, who died in 2011 and willed it to the center, Camilo explained. They were reasonable consolation prizes for not getting into the study, I thought. Che’s real car and a movie prop—the perfect balance of history and myth for his memory today.

As for me, I’d read volume after volume about Che’s peculiar character while researching my book on Cuba, studying his mix of romanticism and icy calculation, his monkish self-discipline, his caustic humor and infuriating moralizing. But learning about his family life had added another dimension, and an extra level of sympathy. Che followed his revolutionary mission with a determination that impressed even his many enemies, but he also wrestled with inner doubts, and knew what he was sacrificing. Writing to his wife from the Congo, he apologized to her for sometimes seeming a “mechanical monster.” And yet, the image that lasted from the trip was from the museum in Santa Clara, where the photograph showed Che smiling as he fed the baby Ernesto with a milk bottle. It’s a contradiction the kids have had to make their peace with. I thought of what Ernestito had told me with a shrug: “Che was a man. You can see the good and the bad.”

Tony Perrottet is the author of six books, most recently ¡Cuba Libre!: Che, Fidel and the Improbable Revolution That Changed World History (Penguin Random House).

Find out more about the book here.

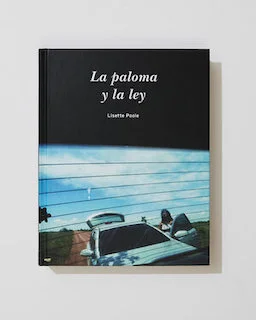

Lisette Poole is a Cuban-American photographer and the author of the book "La paloma y la ley" (The Dove and the Law), the bilingual, photo-illustrated story about two women's journey from Cuba to the US through 13 countries for 51 days. The book was released in October 2019 with Red Hook Editions, now available here.