If the world's smallholder farms used sustainable and regenerative agricultural practices, they could bring us 53% of the way to meeting the United Nations’ net-zero carbon goals.

A hillside slashed and burned, degrading the soil, destroying wildlife habitats and releasing carbon stores into the atmosphere. Adam Cohn CC 1.0

This past February, I worked alongside Sustainable Harvest International (SHI) and their field trainers in Penonome, Panama. SHI is a non-profit organization that opened its doors in 1997 and operates predominantly in Central America, addressing slash-and-burn agriculture, rural poverty, and their connection to climate change.

The Link Between Slash and Burn Agriculture and Rural Poverty

Slash-and-burn agriculture is practiced by 500 million farmers globally. In fact, 20%-30% of deforestation is estimated to be caused by it, directly resulting from a lack of educational opportunities and resources. Similarly, 3.1 billion people worldwide live in poverty, many starving on land ready and available to be farmed. Looking at these issues as one, we’re faced with poverty in rural places and environmental degradation being unavoidably and intrinsically linked.

A smallholder farmer raises fish and livestock or cultivates crops in a limited capacity. In the developing world, a smallholder farm is typically family-owned, and most cultivate less than 5 acres of land. If all 6 million smallholder farmers had the knowledge and training to implement regenerative and sustainable techniques, they wouldn’t have to worry where their next meal was coming from or if their land was healthy enough to be passed from generation to generation. Farmers would no longer have to walk miles to find ground healthy enough to plant for a single season, forced to move further to the following plot the following season. They would have enough food to sustain their families and communities during, for example, a global pandemic—and sell their organic produce at the market for a living wage. Their food would double as medicines, healing bodies from the inside out and healing the soil at once.

What if being able to farm this way simultaneously drew 6 billion tons of carbon from the atmosphere into nutrient-rich soil—the equivalent of shutting down every coal mine? Then, imagine it only costs ~$5,000 for a smallholder farmer to experience and create this transformation.

Many farmers are left with some of the most difficult to cultivate land. They take advantage of the mountainous terrain with terracing. Raeann Mason

Even in the dry offseason, a skilled farmer tends to crops growing on a lush, terraced hillside. Raeann Mason.

Sustainable Harvest International

This is where Sustainable Harvest International comes in. It began as Florence Reed’s dream to mobilize her knowledge, and the knowledge of others, to heal our planet and its people and reverse the effects of climate change through agriculture. As of today, more than 3,200 farmers have been through the SHI program, planting over 4M trees, regenerating over 26K acres of previously degraded land, and building more than 2K clean wood-conserving stoves. And they’re only just getting started. SHI is working tirelessly to scale its programming; by 2030, its goals are to

transform 1 million farms

plant 1 billion trees

sequester 18 million tons of CO2

regenerate 8 million acres of land

achieve food security for 5 million people

I learned quickly that SHI isn’t interested in promises of “going net zero” or slowing the rate at which the atmosphere is warming through offsets. Instead, they work directly with smallholder farmers to prevent more destruction and undo the damage already done in their lives, their land, and the planet’s climate; their work goes beyond sustainability— it’s regenerative.

Sustainable Harvest International’s Field Trainers demonstrate how to use the wind to separate rice husks. Raeann Mason.

A farmer explains how his terraces are braced with grass to prevent runoff. Raeann Mason

How It Works

With Sustainable Harvest International (SHI), farmers commit to learning new methods and receive hands-on tactical training and education. Each program phase lasts around one year, taking 4-5 years and ~$5,000 to complete. SHl hires local field trainers with sustainable and regenerative agroforestry training, local history and insight, and agricultural experience.

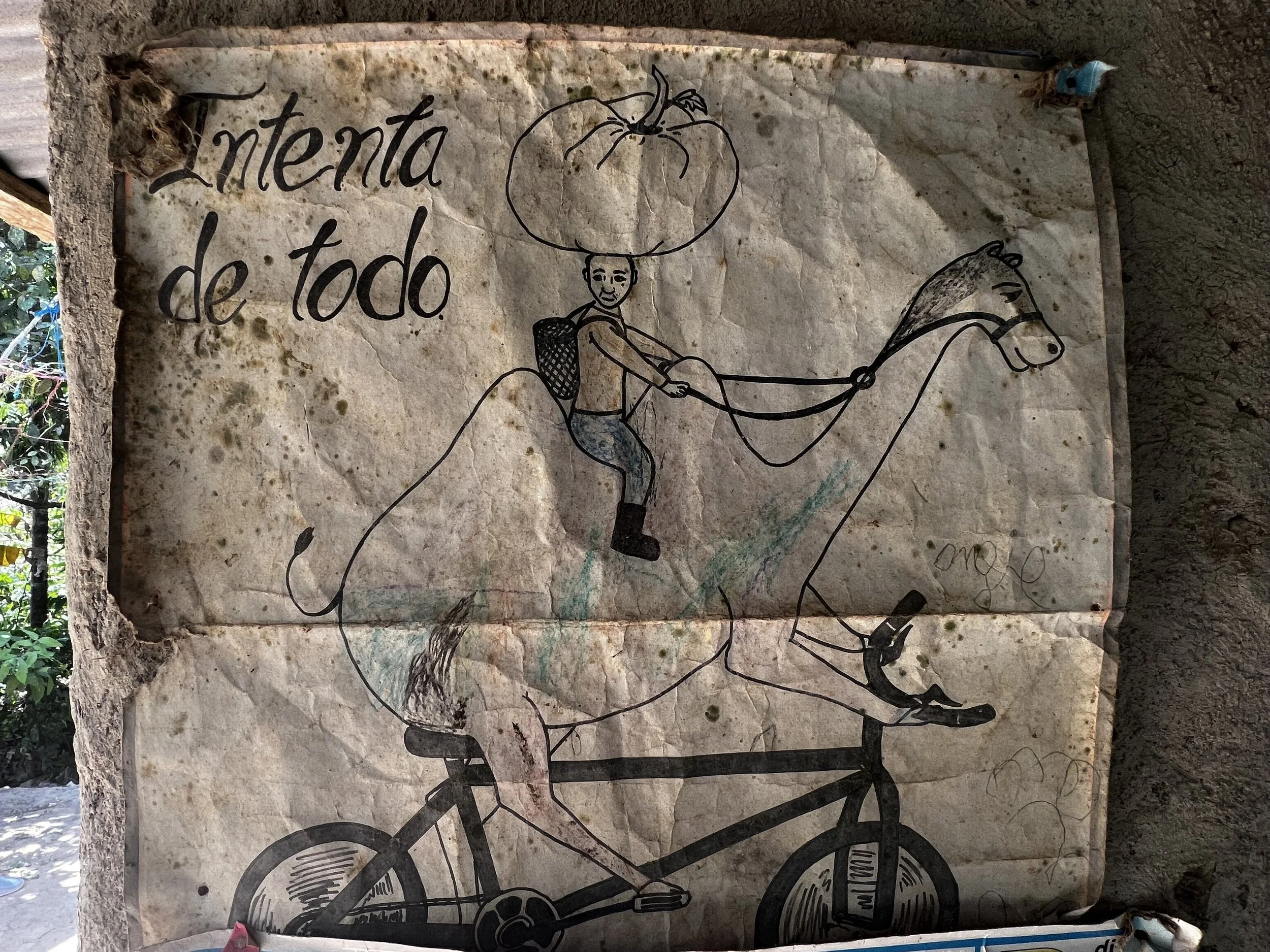

A farmer shares the pictures she drew of her farm in the present day compared to what she hopes her farm will look like by the end of the program. Image courtesy of Sustainable Harvest International.

The Phases

During phase one, farmers and field trainers dream together, planning and plotting how much of their land they’re willing to commit to learning new techniques, discussing long-term goals and drawing a picture of what they hope their degraded land will look like by the end of the program. I was so moved by the hope these colored-pencil drawings provide, and when the program is over, they stand as a testament to the process—how much work it took and how effective it was.

Phase two is about learning new practices, focusing on health and nutrition for the body and the soil. Many of the people I met were subsistence farmers, which means they were growing food to meet their immediate needs to survive; no working farm=no food. When we talk about making changes in our life for the sake of our planet—riding a bike to work, ditching single-use plastics—most of us aren’t faced with the fear that if it doesn’t work out, our ability to survive, for our families to survive, is at risk. This is why when I say these smallholder farmers are the closest people I’ve met to real-life superheroes, I’m not exaggerating. They’re willing to put it all on the line to make a change, not just for themselves but for you and me. Despite years of slash-and-burn tradition and generations of methods passed down, they’re choosing to take the risk on something unknown. They’re choosing to heal our planet. Witnessing this posture of vulnerability, I was forced to grapple with the level of my own (un)willingness to sacrifice and risk-take for the sake of humanity and our shared planet.

A farmer cuts the stalk of a plantain tree for composting. Raeann Mason

Farmers in Panama learn to make “ensalada de vegetales,” in English, “vegetable salad,” which is nutrient-dense compost. Raeann Mason.

I was also struck by SHI’s commitment to maintaining and supporting farmer autonomy, allowing them to choose the type of crops to grow throughout the program. All the farms I visited had a different layout, each an oasis of its own right, with different visions and hopes to meet the families’ needs. Farmers are trained to understand the adverse effects monocropping has on biodiversity and are eager to grow crops ranging from cacao trees, pigeon pea shrubs, herbs and spices, peppers, cucumbers, rice, coffee, yucca, yams, plantains and so much more. One farm, in particular, was set in the trees, a forest of life-giving foods hidden in plain sight, masked by the assumption that farms don’t look like rainforests.

Chocolate growing, hidden in plain sight. Raeann Mason

Coffee harvest. Raeann Mason

Phase three shifts gears from subsistence farming and scales to commercial education and training, which centers on environmental stewardship. Here again, I saw how SHI goes above and beyond the work of typical non-profits. Farmers find themselves with an abundance to sell, and the focus on land restoration and conservation begins to turn the heads of neighboring farmers. The farm starts to take care of itself, money earned allows farmers to thrive, and regenerative practices keep the soil nutrient dense for every growing season. Many farmers will choose a select few crops to grow commercially beyond what they grow for themselves. I saw lots of coffee being produced for this, but instead of a flat field of endless rows of coffee under manufactured shade, the crop was planted alongside plantain trees and corn, scattered about the farms and tucked within treelines; everything felt native.

Phase four is all about business development and micro-finance. The farms I worked on in phase four allowed me to listen and learn in the place of laborious volunteer work. Farmers have been relishing the benefits of adopting regenerative practices during this phase. Their history with the land, the tactical support and guidance of SHI’s field trainers, and the confidence from seeing the literal fruit of their labor meant as a volunteer, there was little I could bring to the table aside from profound respect. There’s an indescribable excitement on farms in this phase, or perhaps it’s being able to sense the weight of living in survival mode lifted.

An SHI stove featured in a farmer’s kitchen set up next to the typical stove, which is the pile of rocks in the lower right corner. Raeann Mason

Demetrio dries coffee beans in the sun. Raeann Mason

In phase five, farmers reach that inevitable state of being a community leader and graduate from the program. Graduation is more of a celebration than a formal affair because by now, the farmers and SHI field trainers are like family—bonding through fear, hope, sweat, body aches and success, freedom and trust hard earned. Some farmers go on to work for SHI as field trainers, and others are hired as consultants within their own communities because their farms can be sustained with much greater ease, while others become the experts in their communities which neighbors look to for advice.

Volunteers take a break from leveling a rice paddy. Kate Herndon.

While most of my time with SHI was spent getting my hands dirty on projects like terracing and planting rice paddies, there was one farm I visited that graduated from the program a decade ago. It was time to size SHI up against the truest test: time. Too often, I see organizations with good intentions come in like a storm, ask people to radically change their methods, and dash once the program is over. But a decade later, Demetrio, the field trainers, and even the founder of SHI, Florence Reed, greeted each other as old friends on a farm resembling a lush oasis or eco-wildlife resort. Demetrio has become so successful with his farm that he’s now hired as a consultant in surrounding communities. He’s a true testament to the effectiveness of the SHI program—friends, community members, and SHI field trainers consider him a bit of a legend because he has been able to grow strawberries on his farm in the mountains of Penonome—something considered impossible for that region. He also attested that during the last government-led health audit, his family walked away with a clean bill of health while neighboring farmers practicing monocropping and slash-and-burn techniques were hit with an onslaught of diagnoses and medications to manage due to a lack of nutrition; an issue SHI trained farmers don’t have to face to the same degree.

Farmers are trained to take advantage of their hilly plots of land by growing tilapia-fertilized and terraced rice paddies. Raeann Mason.

In fact, SHI offers more than tactical agricultural training. Aside from their commitments to climate action and ending and preventing poverty and hunger, SHI is committed to clean water access and sanitation. Many homes utilize unsafe, life-threatening cooking stoves. SHI has worked to increase the life expectancy of women by implementing a safer cooking stove that ultimately requires fewer resources. They also build composting latrines that provide cleaner, eco-friendly, and agriculturally beneficial alternatives to burying human waste. One farm learned to harvest clean, fresh spring water from the mountain top. Another family shared that what they learned about microfinance allowed them to spearhead a community funding program, training other farmers to manage their commercial endeavors and providing grants to help them get started.

An inevitable ripple effect is occurring in Central America, one that you can only understand by listening and learning. It’s always a humbling experience when someone signs up to volunteer, gets their hands dirty, does back-breaking work, and then has the luxury to leave that work behind. But in a more nuanced way, I understand it’s not volunteer work that is planting the seeds of healing, that it’s these smallholder farmers who are genuinely risking it all, making the lifestyle changes and healing the planet by their own hands. So what can we do to support them?

To Get Involved:

There are several ways to support the efforts of SHI. You can start by sharing this article in your network to help spread awareness. Most importantly, there are several ways to donate, including signing up for their Legacy or Sustainer giving programs. You can even see the impact of your donation and travel to a program site in Central America. They offer career opportunities and internships; you could join their mailing list here. Remember, it only costs $1,000 per year, for only 4-5 years, to completely transform a farmer's life and improve the health of our planet.

Raeann Mason

Raeann is the Content and Community Manager at CATALYST, an avid traveler, digital storyteller and guide writer. She studied Mass Communication & Media at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism where she found her passion for a/effective journalism and cultural exchange. An advocate of international solidarity and people's liberation, Raeann works to reshape the culture of travel and hospitality to be ethically sound and sustainable.