Cemented as a piece of cultural iconography of the Inuit Peoples, "Nanook of the North" exemplifies how art and exploitation can coexist.

“Nanook” Harpoon Scene, Musee McCord Stewart, CC0.

A series of onscreen intertitles dash and dance across the screen at the start of director Robert Flaherty’s 1922 documentary "Nanook of the North." Viewers are told of the harsh cold in Eastern Canada's Ungava Peninsula and, more specifically, the difficult process of filming under these conditions. Soon, a man with a fur coat and weathered skin occupies the screen, making direct eye contact with the camera as wind ruffles the fur of his coat. His name is Nanook—or so we are told.

"Nanook of the North" is one of the most cited and celebrated films in history; it is a staple in movie buffs’ collections and academic classrooms alike. And, the film was one of the first twenty-five films to be chosen for the Library of Congress’s national film registry. The film centers on a man named Nanook and his family as they hunt and live in the freezing temperatures of Eastern Canada through both summer and winter. Critics and historians alike have deemed Nanook the “original” documentary film for its then-groundbreaking ethnographic preservation and depiction of Inuit life and culture. Perhaps just as importantly, Flaherty himself has gone down in history as a legendary dramatist and pioneer of the documentary genre.

"Nanook of the North" original promotional poster. Wikimedia Commons. CC0.

Years later, however, the film is now shrouded in mystery, infamy and controversy. Although "Nanook" is groundbreaking, it is also misunderstood by many. Careful watchers will spy an explanation in one of the first intertitles that Nanook was a composite character created by Flaherty to typify his perception of Inuit life. For much of the twentieth century, people considered the portrayal to be both real and accurate. But, as the film itself makes clear, Nanook and his entire on-screen family were characters. The character of Nanook is played by a man named Allakariallak, and his “wife” Nyla is actually a woman named Alice. The suspenseful harpoon hunting scenes and costuming of the characters is both dated and staged.

Despite being well-received upon its release and celebrated continuously since, "Nanook of the North" is both fabricated and anachronistic. Some modern theorists question if the film should even be considered a documentary at all. But, at the same time, documentary film is not solely the reflection of reality and preservation of truth; many documentaries today are simply a depiction of the filmmaker’s worldview and are similarly underlined by personal bias. And, consequently, Nanook is a reflection of Flaherty's bias and life experiences. Flaherty’s father was a mining engineer and geologist, and his mother encouraged Flaherty’s flair for the arts. Moreover, while growing up in Iron Mountain, Michigan near the border of Canada, Flaherty interacted with American traders and trappers as well as Indigenous peoples who also lived near or on the United States-Canada border. His childhood perception of these peoples frame the plot and characterization of Nanook’s family as well as the traders they meet, which were inaccurate by the time of the film’s 1922 release. Flaherty frames himself as an explorer and discoverer when, in reality, by 1922 many Inuit people already used rifles and incorporated western clothing into their outfits. In short, Flaherty’s depiction of Nanook and his family is a romanticized depiction of Inuit culture and life.

Robert J. Flaherty. Arnold Genthe. CC0.

But, in a pre-internet age, the audience had no idea that these images were manipulated and romanticized — they had no way of doing their own research because there were few if any realistic depictions of Inuit life in readily available media. What resulted was “Nanookmania,” a craze among viewers that resulted in the appropriation of Inuit culture. And, although one could make the argument that Flaherty had no idea that this popularity would ensue, he took steps to market the film to profit from the inaccurate portrayal of these people. The fur company Revillon Freres sponsored Flaherty’s film, which featured Nanook and his family in outdated fur coats, as well as a large display of fur pelts at trading post scenes. In many ways, this inaccuracy was an early form of product placement.

“Nyla,” pictured in a fur. Musee McCord Stewart. CC0.

Beyond the marketing and fictional construction of characters in "Nanook of the North", many of the directorial choices both romanticize and exotify the Inuit actors featured in the film. The intertitle cards declare that Nanook and his family are “kindly, brave, and simple,” perpetuating the stereotype that Inuit people are an unintelligent yet loveable people and thereby infantilizing them.

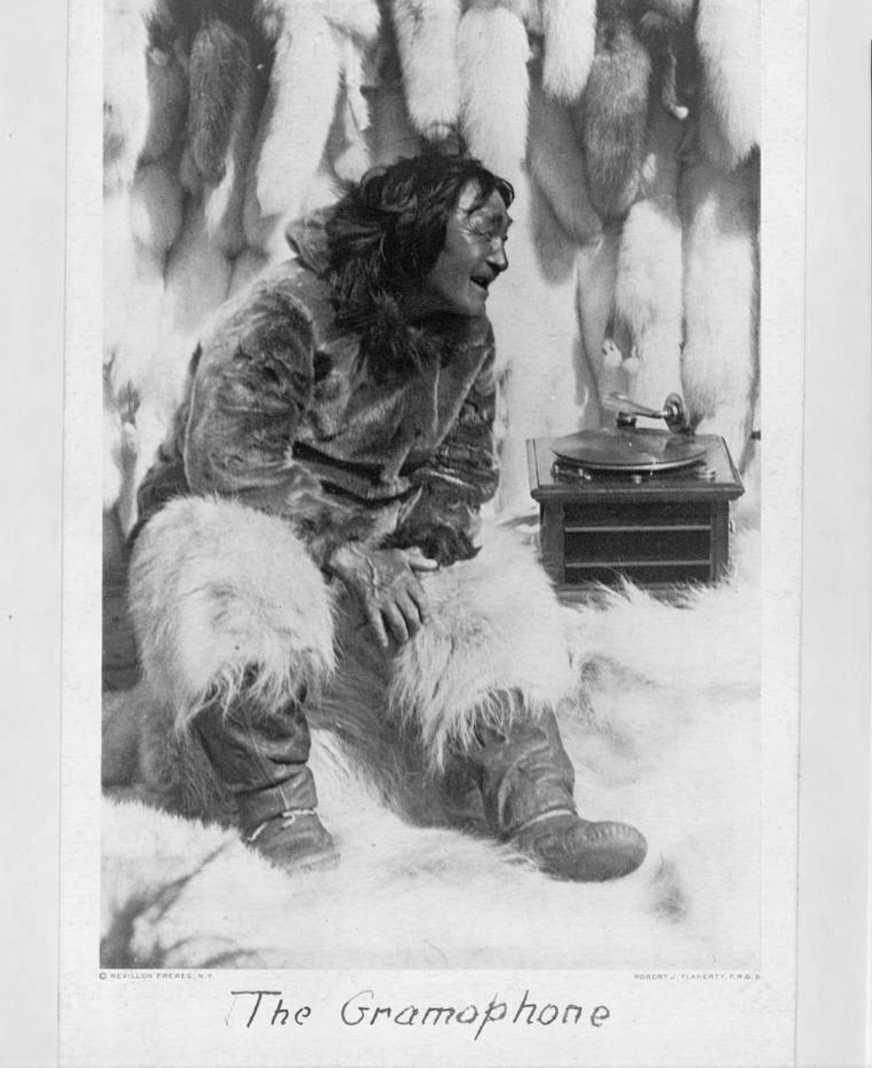

Moreover, in a scene at the trading post, when one of Nanook’s children eats too much biscuit with lard, a white trader feeds the child castor oil and, miraculously, the child is better instantaneously. This scene exalts western medicine and, in turn, harmfully glorifies western ideals and technology. Additionally, while at the trading post Nanook, a grown man, plays with a record player, biting the vinyl and laughing. This scene not only makes a joke out of Nanook’s supposed unfamiliarity with that piece of technology, but also infantilizes him in the same vein as the stereotypical descriptions of the family at the beginning of the film.

The infamous Gramophone scene. Library of Congress. CC0.

Although "Nanook of the North"will forever be considered one of the first documentaries and a dramatic feat by director Robert Flaherty, it is important to note the inaccuracies and misappropriation that riddles the film. Primarily, the movie is a representation of Flaherty’s limited interactions with Inuit peoples, informed by his childhood memories. As "Nanook" lives on in infamy, it is crucial to acknowledge the drawbacks — intentional and not — in Flaherty’s directorial approach.

Carina Cole is a media studies student with a concentration in creative writing at Vassar College. She is an avid journalist and occasional flash fiction writer. Her passion for writing overlaps with environmentalism, feminism, social justice, and a desire to travel beyond the United States. When she’s not writing, you can find her meticulously curating playlists or picking up a paintbrush.