Zoe Lodge

A look into the history and consequence of removal practices against indigenous Australian youth, the “Stolen Generation.”

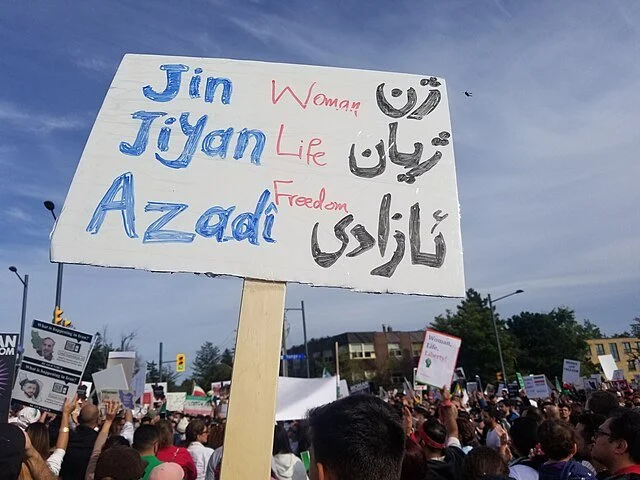

Indigenous Australian children. Mark Roy. CC BY-SA 2.0.

From the early 20th century until as late as the 1970s, Australia carried out a government-sanctioned campaign that forcibly removed Indigenous children from their families in a bid to assimilate them into white society. While much global attention has focused on the legacy of boarding schools for Indigenous children in North America, similar practices were inflicted on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples under British colonial rule, often with the encouragement of the Roman Catholic Church and other Christian institutions. These efforts left generational scars, contributing to the systemic inequality and social fragmentation that persist into the modern day.

This dark chapter in Australian history is commonly referred to as the “Stolen Generation.” According to a report conducted by the U.S. Department of the Interior, which investigated comparable initiatives across the globe, roughly one in three Indigenous children in Australia were forcibly taken from their homes between 1910 and 1970. These children were placed in church- and state-run institutions or sent to live with white families that exemplified Western values, where they were stripped of their language, culture and identity. The underlying goal, both ideological and colonial, was to “civilize” these children by erasing their cultural roots and integrating them into a white-dominated society.

These practices were grounded in a racist belief system that deemed white Australian culture, rooted in Western European culture, inherently superior. Authorities at the time regarded the removal of Indigenous children as a moral duty and a practical solution to what was referred to as “the Aboriginal problem.” In reality, the result was a trauma that has rippled through generations. Children taken from their families frequently endured physical and emotional abuse, neglect, and, in many cases, sexual assault. They were often treated as cheap labor and denied access to adequate education and healthcare.

Although Australia never formally established a network of Indigenous boarding schools akin to those in the U.S. and Canada, the assimilationist mission was no less destructive. Despite making up only about 6% of Australia’s youth population, Indigenous children account for almost 50% of those in out-of-home care, which includes placement in foster care, group homes and with kinship carers. This gaping disparity emphasizes the lasting effects of these programs, leaving First Nations people to deal with dislocation, cultural loss and intergenerational trauma.

In recent years, the Australian government has taken steps to acknowledge and atone for these policies. A national apology was issued in 2008, followed by reparations exceeding $375 million for surviving members of the Stolen Generation. Additionally, individual states have contributed over $200 million in compensation funds for those affected. However, many argue that financial reparations, while important, cannot undo the profound harm caused by decades of systemic cultural erasure and displacement.

Australia’s history with its Indigenous populations is not unique. As the DOI report highlights, these tactics of domination and forced assimilation are not isolated but part of a broader colonial pattern seen across Canada, the United States and New Zealand. These initiatives, driven by the dual forces of governmental policies and religious institutions, sought to erase Indigenous culture in favor of Eurocentric ideals. From the earliest boarding schools in the United States and Canada to parallel programs in Australia and New Zealand, the common thread was the colonial power’s blatant disregard for the autonomy, culture and humanity of Indigenous communities, particularly through religious messaging and values. These institutions inflicted lasting harm, not only by physically removing children from their homes and subjecting them to abuse but also by obliterating the cultural traditions and languages that sustained Indigenous identities for generations.

GET INVOLVED:

One of the primary organizations focused on bringing justice to the First Nations people of Australia is ANTAR, which offers several ways to get involved, raise awareness and contribute to justice for the Indigenous people of Australia. Locals can volunteer with the organizations, and citizens worldwide can contribute to fundraising efforts or participate in global education and awareness campaigns. Other organizations with similar missions include Pay the Rent, IWGIA and the Aboriginal Legal Service.

Zoe Lodge

Zoe is a student at the University of California, Berkeley, where she is studying English and Politics, Philosophy, & Law. She combines her passion for writing with her love for travel, interest in combatting climate change, and concern for social justice issues.