While wealthy nations and corporations benefit from the shift to renewable energy, the poorest and most disenfranchised communities are left to suffer the consequences.

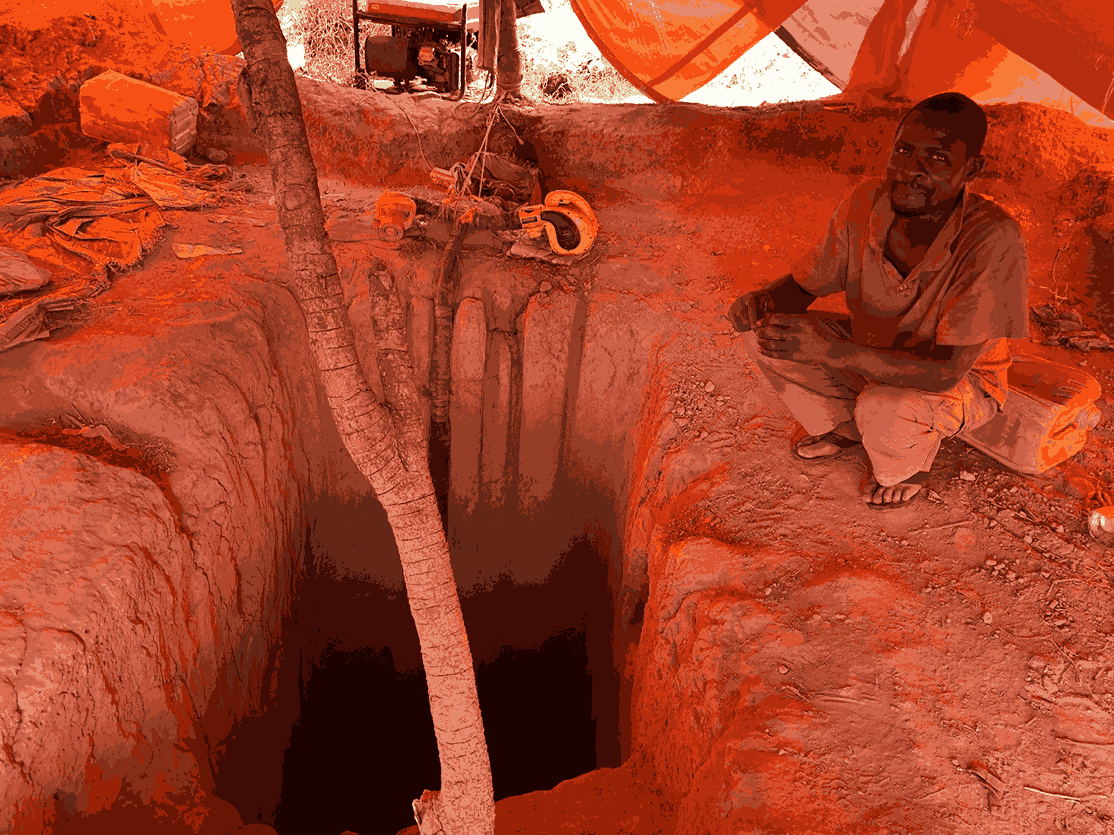

Cobalt Mine. Afrewatch. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

As the demand for renewable energy increases, industrialized countries are racing to obtain metals like lithium, cobalt, zinc, manganese and nickel. These metals are used to make batteries, solar panels and wind turbines—technologies that will ideally enable a transition away from fossil fuels. However, procuring and processing the materials necessary to support these sustainable infrastructures comes with a price that is often overlooked: the human and environmental toll of mining these resources is anything but sustainable for communities worldwide.

Continents rich in these resources— like Africa, Latin America, and Asia—are facing a surge in mining activities, which has in turn led to widespread human rights violations and environmental degradation, particularly among Indigenous communities. According to the Transition Mineral Tracker, there have been 631 human rights abuse allegations against companies involved in the extraction of transition minerals between 2010 and 2022, with 46% of the allegations originating in South America.

Lithium Mine in Argentina. EARTHWORKS. CC BY-NC 2.0

Human Rights Watch has documented a litany of abuses in mining sectors, from child labor and hazardous working conditions to chemical pollution and forced displacement. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is the world's biggest producer of cobalt, a critical component of lithium-ion batteries, which power everything from electric vehicles to smartphones. Child labor remains an issue in the DRC, with more than 40,000 children working in the hazardous conditions of the Katanga province’s cobalt mines, according to data from the United Nations.

These children, victims of trafficking and of necessity, are subjected to horrendous conditions, including frequent mine collapses and prolonged exposure to toxic dust. Their work is grueling, often lasting for 12 hours a day, with little to no protective gear. Some children work with their bare hands. Many suffer from chronic health problems, such as respiratory issues and musculoskeletal disorders, as a result of the substandard working conditions.

Cobalt Mining Site. Fairphone. CC BY-NC-SA

Adults suffer in the mines as well, laboring in slave-like conditions. Cobalt mining tunnels often reach lengths and depths far greater than the legal maximum of 98 feet, an already dangerous level. Poor regulation, governance and lack of incentive to adhere to the law means tunnels can reach lengths of up to 295 feet, a level that threatens extreme risk of collapse, landslides and death for miners.

Conditions underground are hot and dusty, as miners rely on generators for oxygen during their 12-hour shifts, six days a week. Though cobalt is toxic to touch and breathe, miners are constantly exposed to the substance. Exposure to polluted water and air can lead to several health problems, including respiratory illnesses, skin conditions and even cancer. In some mining areas, the rate of birth defects and infant mortalities has increased, raising alarm among local and international health organizations.

Cobalt Miners in the DRC. The International Institute for Environment and Development. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The environmental impact of mining is another major concern. The mining industry has ravaged the landscape of the DRC. Millions of trees have been cut down and the air surrounding the mines is hazy with dust and grit. The mining process often involves the use of hazardous chemicals to separate the desired minerals from the ore. These chemicals can seep into the soil and water, contaminating local water supplies and agricultural land. “In this stream, the fish vanished long ago, killed by acids and waste from the mines,” one Congo resident reported of his childhood fishing hole. In some cases, mining operations have dried up rivers and lakes, devastating local ecosystems and the livelihoods of those who depend on them.

The expansion of mining activities often causes the displacement of entire communities, whether by pollution or force. Data from the Business & Human Rights Resource Center points to widespread violations of Indigenous peoples’ rights—such as forced relocation, water pollution and denial of access to traditional land—as well as attacks on human rights defenders and workers’ rights abuses. In countries like Indonesia, Peru, Columbia and Bolivia, mining operations have displaced Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands. These displacements not only disrupt the social fabric of communities but also erode cultural identities that are deeply tied to the land.

In many cases, those who resist displacement or speak out against mining abuses face retaliation. In Indonesia, local officers were accused of breaching police ethics through the use of intimidation tactics, carrying around weapons to compel people to leave their ancestral village. There have been numerous reports of police violence and arbitrary arrests of activists who oppose mining projects. In Colombia, a mine was built within the sacred territory of the Embera people, without any consultation with Indigenous locals. The community faced forced displacements, the territory was militarized, and leaders who spoke out about human rights violations became targets of harassment.

As the demand for green energy continues to rise, companies that rely on these materials must ensure that supply chains are free from exploitation. This includes due diligence, supporting fair labor practices, and investing in cleaner and more sustainable mining technologies. Governments also have a role in regulating the mining industry and protecting the rights of vulnerable communities. Stronger international regulations, greater transparency and accountability are essential in preventing abuses and ensuring that the beneficiaries of the green energy transition are not limited to corporations.

GET INVOLVED

GoodWeave: Founded in 1994 by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Kailash Satyarthi, GoodWeave is a leading nonprofit organization in the fight to stop child labor in global supply chains. The institution partners with companies and local producer communities to bring visibility to hidden supply chains, protect workers’ rights, provide assurance that products are free of child or forced labor, and support exploited children.

Good Shepherd International Foundation: Good Shepherd International Foundation works to support women, girls and children living in vulnerable and impoverished conditions. They protect and promote the rights of people affected by poverty, human trafficking, child labor, and other human rights violations in over than 30 countries.

Global Witness: Global Witness works to hold companies and governments accountable for ecological destruction and the failure to protect human rights. The organization campaigns to end corporate complicity in environmental and human rights abuses, end corporate corruption, hold companies in the natural resource sector to the law, and protect activists standing up to climate-wrecking industries.

Rebecca Pitcairn

Rebecca studies Italian Language and Literature, Classical Civilizations, and English Writing at the University of Pittsburgh. She hopes to one day attain a PhD in Classical Archeology. She is passionate about feminism and climate justice. She enjoys reading, playing the lyre, and longboarding in her free time.