Despite being protected within the Indian constitution, hijra communities experience persecution. Their colonies are often sites of abuse and poverty, yet serve as the only space in Indian society for their identity.

Image by Carol Foote

India’s third gender includes a few different groups, but the most common are the hijras. The hijra identity is complex; some are born male but dress in traditionally feminine ways, some are born intersex, some seek gender reassignment procedures, and some choose to be castrated as an offering to the Hindu goddess of chastity and fertility, Bahuchara Mata, granting them their religious powers. Outsiders tend to associate them as transgender, but Indian society considers them to be the third gender — not male, not female, not transitioning. The one defining characteristic of hijras is that they leave their homes from a young age to become a part of the hijra community, where they teach their lessons in secret. These communities exist on the outskirts of society, where they are often shunned by their families and at the mercy of police authorities.

Image by Carole Foote

For centuries, trans, intersex and genderqueer individuals abandoned by their families have been initiated into the hijra community by gurus within the system. From the age of 12 or 13, hijras trade their relationships with their families for a relationship with a guru who takes on the role of of parent, teacher and boss. The gurus are expected to teach each hijra the chela, or the disciple, in the hijra way of life. This includes learning their rituals, how to manage a household and how to make a living. Gurus are expected to treat the hijras like their children, but their ability to dictate how a hijra works, what they earn and even who they see maintains a hold over their lives that many activists consider a systemic form of bonded labor.

Image by Carol Foote

These communities operate within a pyramid system where the “chelas,” or the hijra students, are divided into hierarchies by their work. At the top of the pyramid are the senior-most chelas, who sing and dance. Below them are the chelas who beg and collect alms in exchange for blessings at events. And lastly, at the bottom of the chela pyramid are the sex workers. In addition to their work, chelas are expected to take on chores that serve their guru. Regardless of how a hijra earns their money, a portion of it will go to their gurus.

Image by Carol Foote

The founder of online transgender community Transgender India, Neysara, told NewsNewslaundry,aundry, an independent news media company in India, that the hijra community is “not a child-friendly place equipped to handle trauma.” She went on to say that, “What is vulnerable is trafficable and most that join are disenfranchised.” Neysara recalled turning to the hijra community at a time when she was young and scared. “When my family was trying to honor-kill me, I sought the hijra jamaat for help. They outright told me that I [...] could only stay with them if I do sex work and earn for them.” Honor killings are committed by a male family member seeking to protect the dignity of their family against someone they believe has brought them shame. It was sex work or death.

Image by Carol Foote

Hijras have been a part of Indian life for more than a thousand years. Evidence of their existence within Hindu society can be found inside holy texts like the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, where Arjuna became the third gender. Throughout South Asian history, third-gender people have often held positions of high power. For example, during the Mughal Empire in the 15th to 19th centuries, Hindu and Muslim rulers were considerate advocates of the third gender, and many rose to significant positions, even serving as the sexless watchdogs of Mughal harems. In Hinduism, their high regard is marked by their loyalty to Lord Rama, when hijras waited at the edge of the forest for 14 years until he returned to Ayodhya after being exiled.

Image by Carol Foote

The hijras’ religious backgrounds tend to center around traditions that blend Hinduism and Islam. The practice of removing genitalia is something stigmatized in a normal Indian community, however, it’s this act that is the source of their sacred power and legitimizes their role in society. According to tradition, when a hijra is castrated their genitalia is offered to the Hindu Mother Goddess, Bahuchara Mata. The Mother Goddessworks alongside Muslim saints to transform the sacrifice of their ability to procreate into the power to bestow fertility and good luck onto others. The hijras give blessings at births and weddings to grant new couples and their newborn children fertility and prosperity. Intersex people, transgender women and infertile men are considered to be called upon by the goddess to become a hijra. Should they ignore the call, it is believed that they will pay the price of being impotent for the next seven lives they have on Earth.

Image by Carol Foote

The castration surgery is performed by a guru and takes place without an anesthetic. The operation is illegal and life-threatening and has led some Indian regions to consider offering a medical alternative free of charge. However, because of tradition, the sacred sacrifice is performed in absolute secrecy and never spoken of. Following the surgery, new hijras recover in semi-seclusion and eat a special diet for 40 days. Afterward, they conduct a special ceremony where they're dressed as brides and blessed with the power of Bahuchara Mata. From this moment on, they are given new names and new identities. Articles in the India Times and India Today have reported how this system has been forced upon young and at-risk men, who are then pressured into prostituion and homosexuality.

Image by Carol Foote

Even though hijras were treated with respect for thousands of years, much of their societal downfall can be attributed to Hinduism’s encounter with colonialism. The British colonized most of South Asia in the 19th and 20th centuries, and their Christian beliefs did not prepare them for their confrontation with the third gender. In 1871, the British named all hijras hereditary criminals and ordered authorities to arrest them. The law gave police the power of increased surveillance over the community, who went as far as to compile registers of hijras. A historian named Dr. Jessica Hinchy told BCC that, "Registration was a means of surveillance and also a way to ensure that castration was stamped out and the hijra population was not reproduced."

Image by Carol Foote

Even though the law was repealed once India regained its independence, 200 years of stigmatization took a toll. Today, hijras are almost always excluded from employment and education outside of their religious roles. They are often stricken by poverty and forced to resort to begging and prostitution. Most are victims of violence and abuse, harassed by police and refused treatment in hospitals.

Image by Carol Foote

In a step forward, India’s Supreme Court officially recognized hijras as a third gender in August of 2014, in a law that ordered the government to provide third gender people with quotas in jobs and education. The ruling came just six months after the Supreme Court’s decision to re-criminalize homosexual acts through the reversal of a 2009 Delhi High Court order.Despite being legally recognized and protected under the Indian Constitution, the court’s choice meant that hijras would be breaking the law if they participated in consensual homosexual relations.

Image by Carol Foote

As Neysara told NewsLaundry, “without trans representation, laws made by cis people for the ‘other’ can be damaging.” Prior progress gained seemed to be lost in 2019 when activists protested the Transgender Persons Act. According to Ajita Banerjie, a Delhi-based gender and sexuality rights researcher, this “set the whole movement back by a decade.”

Image by Carol Foote

Today, as many as half a million members of the Indian hijra community live within the guru-chela system. Despite facing discrimination, abuse and living on the margins of society, the community continues to “remain a visible presence in public space, public culture, activism and politics in South Asia," Dr. Jessica Hinchy told BBC. On a high note, NewsLaundry says that policy-led interventions have been advocated by stakeholders in the system, with the mission to integrate “trans folks into mainstream society to reduce and ultimately end their dependency on this system, if not the system itself.”

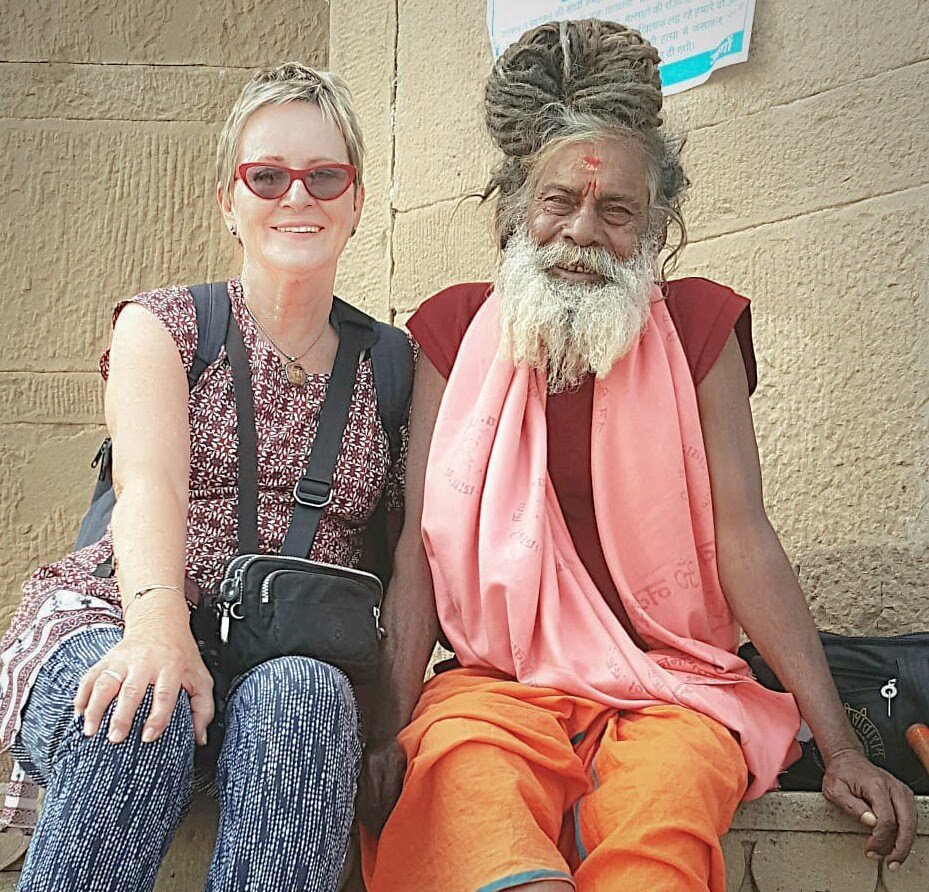

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER:

Carol is based in Queensland Australia and has always been drawn to street photography, searching out the most colourful and quirky characters in her own environment. After studying documentary photography at college, she travelled to Yunnan, China to photograph the wide diversity of ethnic minorities in the region. However, over the past five years, her focus has shifted to Tibet, Nepal and India. As someone who has always been drawn to unique and different cultures, the regions rich heritage and local traditions make it a haven for her style of photography.

Claire Redden

Claire Redden is a freelance journalist from Chicago, where she received her Bachelor’s of Communications from the University of Illinois. While living and studying in Paris, Claire wrote for the magazine, Toute La Culture. As a freelancer she contributes to travel guides for the up and coming brand, Thalby. She plans to take her skills to London, where she’ll pursue her Master’s of Arts and Lifestyle Journalism at the University of Arts, London College of Communication.