Photographer Laura Grier shares her adventures through Bosnia, Croatia, Montenegro and more.

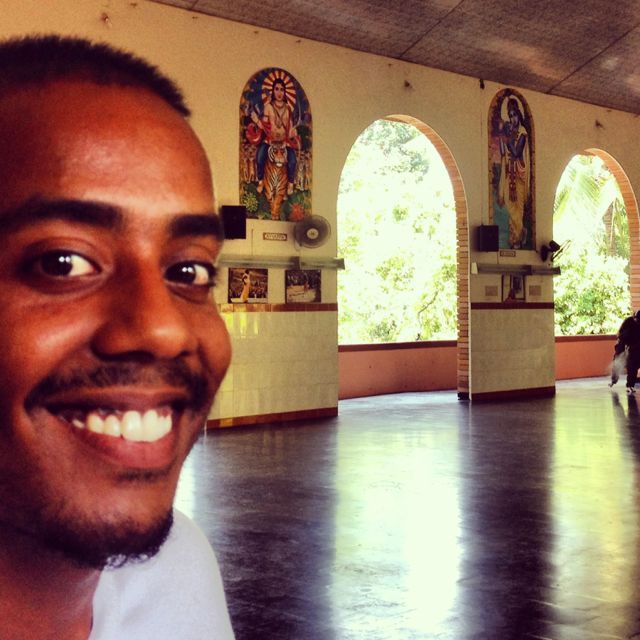

Macedonia. Laura Grier.

Imagine hitting the road with your best friends, traveling through the breathtaking Balkans, in the heart of the former Yugoslavia. A journey through some of the most stunning landscapes in Europe, this epic road trip was also a personal milestone for me as I celebrated visiting my 100th country along the way.

Although many Americans don’t often travel to this part of the world, Eastern Europe is a hidden gem — safe, welcoming and incredibly affordable. Crossing borders was a breeze, even though we didn’t speak the local languages. Everywhere we went, from bustling cities to quaint villages, we were greeted with warm smiles and genuine hospitality.

The mix of rich history, mouth-watering food and awe-inspiring nature made my trip unforgettable. Whether exploring medieval fortresses perched on cliffs, wandering through picturesque towns, or relaxing by crystal-clear lakes, every moment offered a new adventure. A must-visit destination for any adventurous traveler, this beautiful and often overlooked part of the world is a treasure trove of experiences waiting to be discovered.

1. Bosnia

Mostar Bridge:

The iconic Stari Most, or Mostar Bridge, is both a stunning example of Ottoman architecture and the site of a centuries-old tradition. As a rite of passage in Bosnia, young men often gather on the bridge to prove their bravery by diving 70 feet into the Neretva River which runs below.

Jajce:

The town of Jajce, with its picturesque waterfalls and medieval charm, looks like something out of a fairy tale. Perched high up on a hill between the crossroads of two rivers, this enchanting walled city is also the birthplace of Yugoslavia, making the village as historically significant as it is beautiful.

2. Macedonia

Lake Ohrid:

Lake Ohrid, one of Europe's oldest and deepest lakes, cradles the ancient city of Ohrid. Believed to be the oldest human settlement in Europe, archaeological evidence suggests that the area has been inhabited for over 7,000 years. One of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Europe, the town itself dates back to at least the 4th century BCE. Featuring serene waters and historic sites, Ohrid is truly a gem amongst UNESCO World Heritage sites.

Bay of Bones:

The Bay of Bones is an extraordinary archaeological site that reconstructs an ancient lake settlement from 1200 B.C.E. The floating village, resting upon Lake Ohrid, offers a glimpse into the life of Macedonia's earliest inhabitants. The actual ruins of the original settlement lie underwater, just beneath the recreated floating village. You can even book a snorkeling or scuba tour to explore them up close!

Matka Lake:

Located in Macedonia’s Matka Canyon, Matka Lake is a haven for nature lovers and adventurers alike. Beyond crystal-clear waters and dramatic cliffs, this stunning natural gorge is also home to hidden caves and medieval monasteries, making it a must-visit in Macedonia. You can hike up the nearby mountain to visit the church at the top and then hike back down to swim and do watersports in the lake. However, it’s important to remember that the water temperature can be as cold as 48 degrees Fahrenheit depending on the season. The lake's cool temperature is due to the depth of the canyon and the icy waters from nearby underground springs, making it feel more like a polar plunge!

3. Croatia

Plitvice Lakes:

Visiting Plitvice Lakes National Park feels like stepping into a fantasy, with its breathtaking wonderland of cascading waterfalls, lush greenery and mesmerizing turquoise lakes. This UNESCO World Heritage site is Croatia's natural treasure, captivating visitors with its otherworldly beauty. Plitvice is home to 16 interconnected lakes, each more stunning than the next. I was obsessed with the beautiful neon green moss that covered everything around them.

Dubrovnik:

Dubrovnik, often called the "Pearl of the Adriatic," is a city where history comes alive. With ancient stone walls, charming streets and panoramic views of the sparkling sea, this medieval city is a stunning blend of ancient architecture and vibrant culture. In Dubrovnik, "Game of Thrones" fans will recognize numerous filming locations from the series, such as King's Landing. Walking through the town’s streets might just feel like stepping into Westeros!

Split:

In Split, the past and present beautifully collide. Once the site of a Roman emperor's palace, Split is a vibrant blend of ancient history and modern life. With its sprawling complex of ruins, the UNESCO-listed Diocletian's Palace forms the heart of this bustling coastal city. The narrow streets are interconnected and labyrinthine — you will need to allow yourself time to get lost and discover hidden bars and restaurants, some of which haven't changed in centuries!

4. Montenegro

Tara Canyon:

Tara Canyon, the second deepest canyon in the world, is one of Montenegro's most jaw-dropping natural wonders. With dense forests and a crystal-clear river carving through the rugged landscape, the site is a dream come true for adventurers and nature lovers. The Tara River is known as the "Tear of Europe" because of its pure, drinkable waters. If you're into white-water rafting, this canyon also offers some of the best in Europe!

Kotor:

Visiting Kotor felt like time-traveling to the medieval past. Nestled between dramatic mountains and the shimmering Bay of Kotor, the town is a popular stop on European cruises. While it seems impossible for the narrow bay to accommodate cruise ships, these boats nonetheless manage to bring in thousands of tourists. You can spend the day kayaking out to churches on tiny islands, exploring caves, getting lost exploring the cobblestone streets, and visiting impressive fortifications dating back to the Venetian era.

5. Slovenia:

Predjama Castle:

A medieval fortress built into the mouth of a cliff cave, Predjama Castle is truly a sight to behold. This marvel of engineering holds a Guinness World Record as the largest cave castle in the world (which I didn't know was even a thing)! I love exploring secret passageways and caves and was fascinated when I discovered that the castle’s secret hidden tunnel was used by Erasmus of Lueg to sneak out and bring in supplies during a siege. Exploring this castle felt like diving straight into an “Indiana Jones” movie!

Slovenia’s Coastline:

Slovenia’s spectacular coastline may be small, but it packs a punch with its crystal-clear waters and pristine white pebble beaches. It is truly a hidden gem, perfect for those looking to escape the crowds. Piran, a charming coastal town, is often compared to Venice for its Venetian-style architecture and stunning views of the Adriatic Sea.

Slovenia as "Narnia":

If you've ever dreamed of stepping into a fairy tale, then Slovenia is the place for you. The country’s enchanting landscapes, rolling hills and ancient forests are so magical that they served as a backdrop for "The Chronicles of Narnia" films. Driving through Slovenia, every turn reveals a new and breathtaking scene. It felt like Narnia came to life — and I never wanted to leave!

6. Serbia:

Fields of Sunflowers and Agriculture:

Who knew that Serbia was a land of endless sunflower fields and rich agriculture? When I first drove into Serbia, I couldn’t help but feel like I was in the Midwestern United States. Northern Serbia, with its flat terrain, was once an ancient seabed, which is why the soil is so nutrient-rich. This makes it perfect for growing crops that stretch as far as the eye can see, creating stunning golden landscapes in the summer.

Belgrade:

Serbia’s capital, Belgrade, is a city with a rich and tumultuous history. Its most famous landmark, the Belgrade Fortress, has stood the test of time, watching over the Sava and Danube rivers. This fortress has seen everything from medieval battles to World War II skirmishes. Today, it’s a beloved park and museum, offering panoramic views of the city and a peek into the hidden tunnels and bunkers used during World War II. The underground armory inside the castle was even converted into a popular underground disco tech in the ’90s. I love how this region of the world has embraced its tumultuous past and incorporated it into modern life in creative ways.

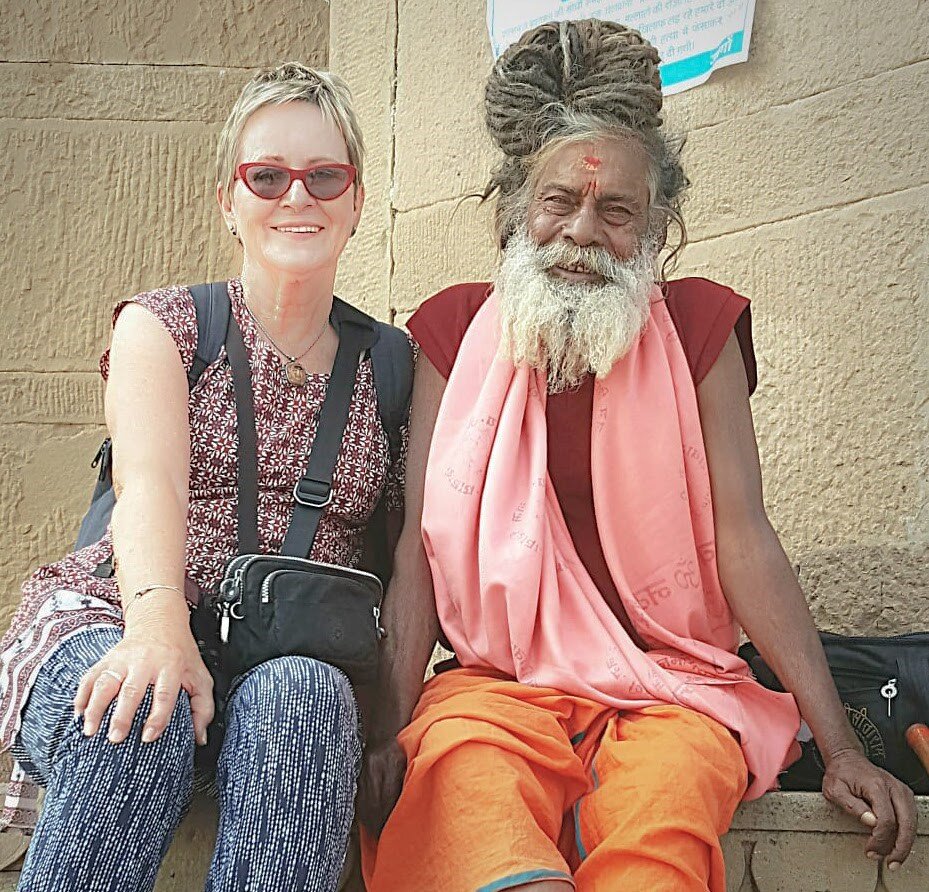

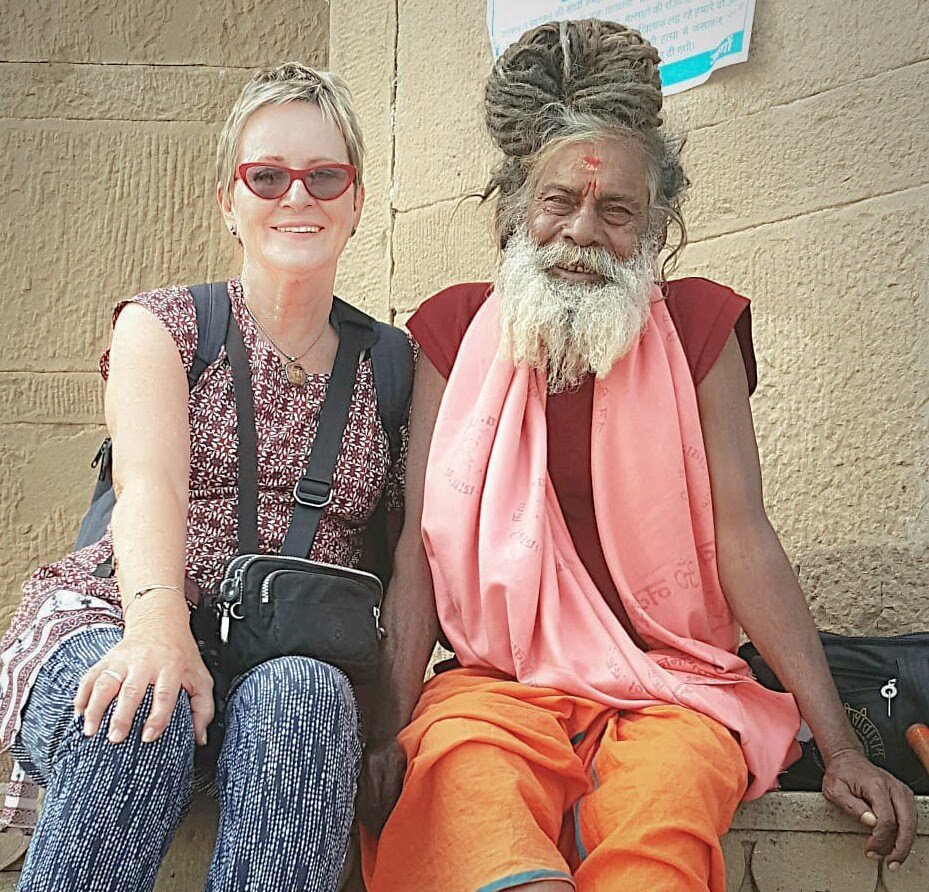

Laura Grier

Laura is a dynamic Adventure Photographer, Photo Anthropologist, Travel Writer, and Social Impact Entrepreneur. With a remarkable journey spanning 87 countries and 7 continents, Laura's lens captures both the breathtaking landscapes and the intricate stories of the people she encounters. As a National Geographic artisan catalog photographer, Huffington Post columnist, and founder of Andeana Hats, Laura fuses her love for photography, travel, and social change, leaving an impact on the world.