India is now the fourth country to land on the moon, and its lunar rover is making some big waves in space exploration.

The Chandrayaan-3 lunar exploration craft was launched from the south of India on July 14. Sky News. CC BY-SA-NC 2.0

On August 23, the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) landed its Chandrayaan-3 craft near the moon’s south pole, marking both the country’s first ever moon landing and the world’s first on that specific lunar region. Not only has this achievement finally placed India among the ranks of other space exploring nations, but has also made it one of only four countries to land a craft on the moon. The location of the craft’s landing near the unexplored south pole is significant given the multiple failed attempts by other nations to do just that in the past and stake a claim to lead future research in the area. Chandrayaan-3’s successful landing will hopefully cement the credibility of the ISRO on the international playing field and allow for continued collaboration with other foreign space agencies. During its two-week lifespan, the rover investigated the existence of frozen water deposits beneath the surface of the moon, and has made a number of surprising discoveries that orbiting crafts were unable to.

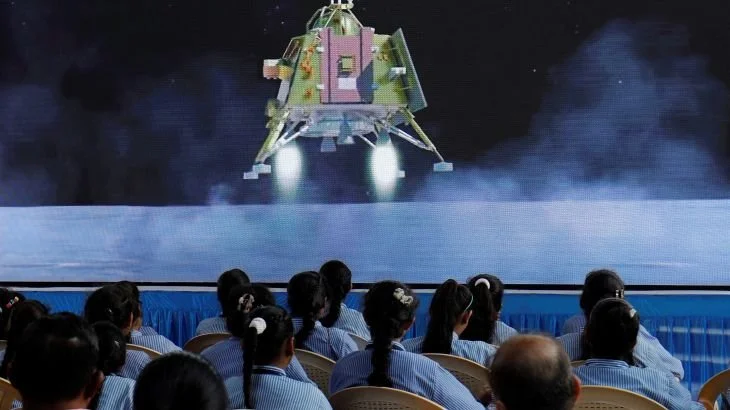

A digital rendering of the Chandrayaan-3 craft and its lunar rover. NDTV. CC BY-NC 2.0

While India’s space program was first established in 1962, it took another decade or two for the ISRO to really pick up steam. Many of the first projects involved sending satellites up into Earth’s orbit in order to map and survey the country from above, bringing telemedical and communication services to communities in remote regions. Chandrayaan, a Sanskrit term meaning “mooncraft,” is the name of India’s lunar exploration program, which made its debut between 2008 and 2009 with the Chandrayaan-1 lunar space probe, which found water deposits on the moon using various mapping techniques and reflection radiation. The next craft, launched in 2019, was comprised of an orbiter, moon lander and rover, and was actually intended to be the first to land on the south pole of the moon, but after successfully entering lunar orbit, the ISRO lost communication with the landing craft and rover before touchdown.

Chandrayaan-3 is therefore the culmination of more than a decade of scientific research and technological development and is undoubtedly the crown jewel in India’s space program. The probe was launched on July 14 from Sriharikota Range, the country’s largest launch site located in the southern state of Andhra Pradesh, and successfully touched down on the moon on August 23. Unlike its recent predecessor, the Chandrayaan-3 traveled without an orbiter module, further cementing its intention to land on the moon and conduct experiments in situ. Additionally, while this craft was unambiguously an Indian project and creation, some of the technology on board resulted from various collaborations between the ISRO, NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA), proving once again the importance and benefits of scientific collaboration.

Students in India watch a video explaining the lunar mission. Al Jazeera. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Aside from proving that landing on the south pole of the moon is indeed possible, the information sent back by the Chandrayaan-3 rover has already resulted in some groundbreaking discoveries about the moon. One such finding has to do with understanding the temperature of lunar soil, an important factor when considering building long-lasting structures or even settlements on the moon. The Indian rover is equipped with a temperature probe that can reach nearly four inches (10 cm) beneath the surface, and found that the temperature drops 140ºF (60ºC) at a depth of just roughly 3.14 inches (8 cm). This has provided an updated and more accurate reading as compared to the data currently in use from NASA’s 2009 Lunar Reconnaissance mission, which lacked precision because it was an orbiter and therefore not actually on the lunar surface. Another interesting discovery took place in the form of a series of strange vibrations detected by the rover’s seismograph: scientists have suspected it as being a minor moonquake, although further exploration and longer-term observations would need to confirm this.

While these scientific discoveries are of course extremely significant and promising for the future of lunar exploration and research, the Chandrayaan-3 project also set a historic precedent in terms of the budget they used to complete this mission. The ISRO has a long held reputation amongst international space research circles for their ability to work on limited funds, at least compared to other major space exploration agencies. NASA, for example, has a $25.4 billion budget for the current fiscal year, while the ISRO received a measly $1.5 billion from the Indian government for the fiscal year ending this March by comparison. If that wasn’t enough, the ISRO actually spent 25% less than what it had been allocated. The Chandrayaan-3 mission cost a total of $74.3 million USD, ironically less than half of the budget that director Christopher Nolan had to make Interstellar, his award winning film about space travel.

The actual Chandrayaan-3 craft before it was launched into space. The Week. CC BY-SA 2.0

In addition to finally taking its place amongst the other lunar landing nations, Chandrayaan-3 has opened countless doors for both the ISRO and the space exploration community as a whole. Going forward, the example that this mission has set with regards to the resources it used as well as through the international collaboration it benefitted from. The moon’s south pole has now been unequivocally proven accessible and investigable, new information about lunar composition has been brought to light, and like all other missions into space, has helped to deepen our understanding of both the universe and ourselves.

Tanaya Vohra

Tanaya is an undergraduate student pursuing a major in Public Health at the University of Chicago. She's lived in Asia, Europe and North America and wants to share her love of travel and exploring new cultures through her writing.