With psychedelic drug reform still underway, research indicates that microdosing may be useful for medical and therapeutic treatment.

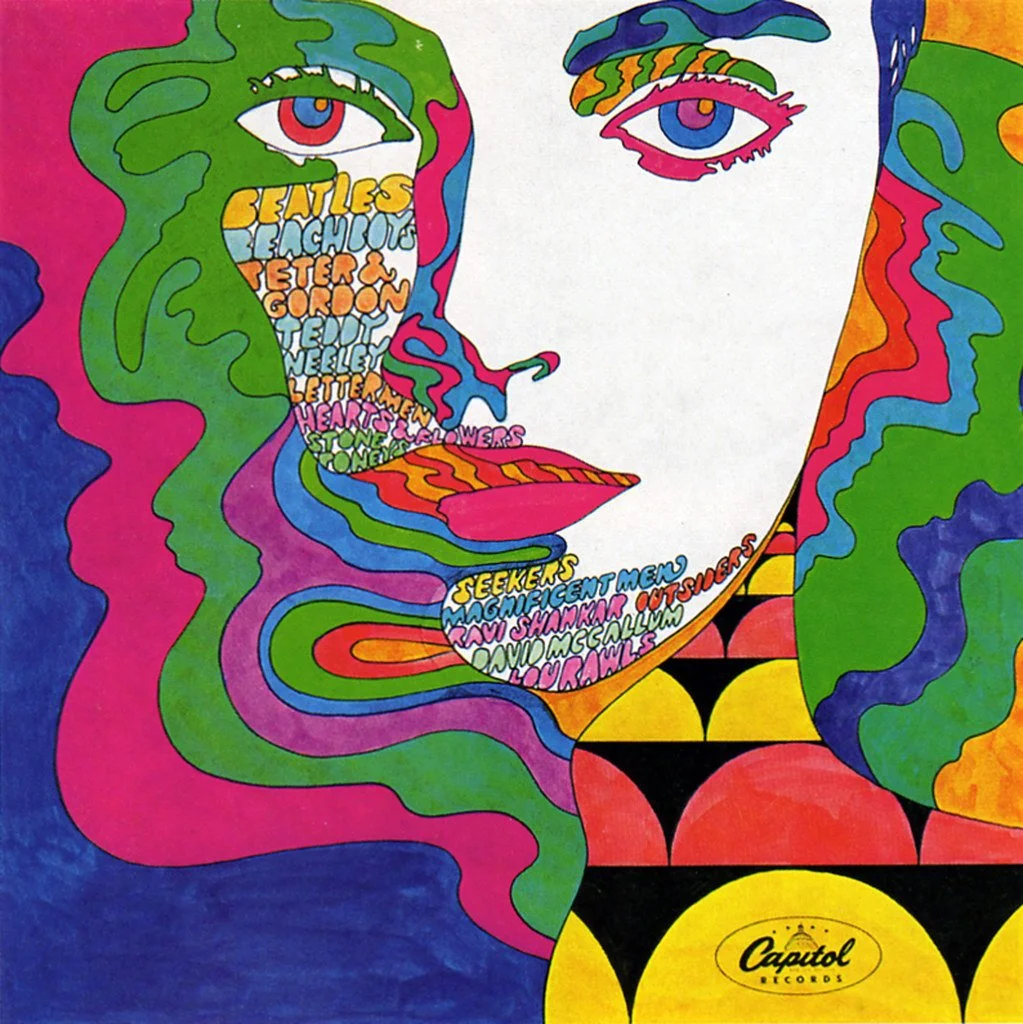

Capitol Records Cover. Daniel Yanes Arroyo on Flickr. CC BY-NC 2.0

In the 1960s, psychedelic drugs became central to counter cultural identity, as they were believed to expand human consciousness and helped inspire the era’s writing, art and music scene. Their acceptance only went so far, however, the war on drugs led to the ban of psychedelic drug use in 1968. These drugs include psilocybin mushrooms (magic mushrooms), MDMA (ecstasy, molly), and LSD (acid). But recent studies show that psilocybin may be used to treat alcohol and tobacco dependence, as well as mood disorders like anxiety, depression and OCD. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has already declared psilocybin as a “breakthrough therapy,” with growing evidence for its efficacy in treating cases of depression that have proven resistant to psychotherapy and traditional antidepressants.

Psilocybin mushrooms. Mushroom Observer on Wikipedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0

Some argue that the legalization of psychedelic drugs would be positive, with regulated companies outcompeting the black market and manufacturing safer drugs (e.g., there would be little risk of products being laced with fentanyl). The status of drug policy reform varies across the U.S. Some states—including Washington, Texas and Connecticut—are actively studying the medical effects of psilocybin. In California, several cities, including Oakland, Santa Cruz, Arcata, Berkeley and San Francisco, have already passed resolutions to decriminalize the possession of psychedelic drugs, excluding peyote. The use of peyote in Native American ceremonies and sacraments is protected under the First Amendment of the Constitution as a form of Free Exercise of Religion. Despite this, the supply of Peyote is severely limited, to the point of being listed as vulnerable to extinction on the IUCN Red List. In several states, including New York, Florida and Utah, legislators have introduced bills to legalize psilocybin for clinical use that ultimately failed to pass. Psychedelic drugs remain illegal under the Controlled Substances Act at the federal level in the U.S.

Legislation varies even more worldwide, but many countries have less stringent laws than the United States. In Australia, MDMA and psilocybin may be prescribed for PTSD for depression. In the Bahamas and British Virgin Islands, psilocybin is legal to possess but not to sell. In Mexico, citizens cannot be prosecuted or charged if psilocybin is used for spiritual or religious purposes. Most of Europe has either decriminalized or deregulated aspects of the use or trade of psychedelic drugs, including countries like Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. The definition of “decriminalization” varies, but usually implies that one can possess a certain amount of a substance avoiding fines or other penalties, despite it being illegal.

While concerns regarding the safety of psychedelic drugs are and will continue to be raised, statistics show that emergency room visits related to psilocybin and LSD are infrequent. Legalizing psychedelic drugs would signify for advocates a stride toward personal autonomy, enabling individuals to make informed choices about what they put in their bodies. This shift mirrors a growing global interest in investigating the therapeutic and medical potential of psilocybin, prompting a reevaluation of 20th century policies.

Agnes Moser Volland

Agnes is a student at UC Berkeley majoring in Interdisciplinary Studies and minoring in Creative Writing, with a research focus on road trip culture in America. She currently writes for BARE Magazine and Caravan Travel & Style Magazine. She is working on a novel that follows two sisters as they road trip down Highway 40, from California to Oklahoma. In the future, she hopes to pursue a career in journalism, publishing, or research.