Japanese birth rates are falling exponentially, and it could have major effects on the country’s economy.

Harajuku District in Japan. @paulkrichards. Instagram

Many around the world consider Japan a futuristic country, a view drawn from its creative technology and its unique culture. A popular destination for tourists all around the world, this East Asian country makes up 1.6% of the world’s population with its approximately 125 million residents.

However, this number is set to rapidly decline as Japan teeters on the precipice of a population crisis. Its Prime Minister has issued a dire warning, saying that the country is “on the brink of not being able to maintain social functions” due to the falling birth rate. Japan has one of the highest life expectancies in the world, which means that most will grow old and require care from others, but the workforce is shrinking as aren’t enough young people to fill the gaps in Japan’s stagnating economy.

Why is this? To use simple terms, Japanese people are having fewer babies. Women are postponing their marriages and rejecting traditional paths to focus on their professional lives, and the percentage of women who work in Japan is now higher than ever. However, there are also fewer opportunities for young people, especially men, in the country’s economy. Since men are still widely viewed as the breadwinners of the family, a lack of good jobs would also mean the men would avoid having children — and settling down — knowing they can’t afford it. With Japan’s high cost of living, it adds more reason for couples to steer clear of having a family.

The problem has only gotten worse since the Covid pandemic. In 2021, the birth rates in Japan declined to around 805,000 — a figure that was not expected until 2028. With much of the population choosing to focus on their careers instead, this number will only continue to fall.

In the early stages of the pandemic, there were jokes circulating that the lockdowns would cause another baby boom. However, the opposite came true. Japan experienced a reduction in birth rates, as well as other countries such as Taiwan and China — to an estimated 1.07 children per woman.

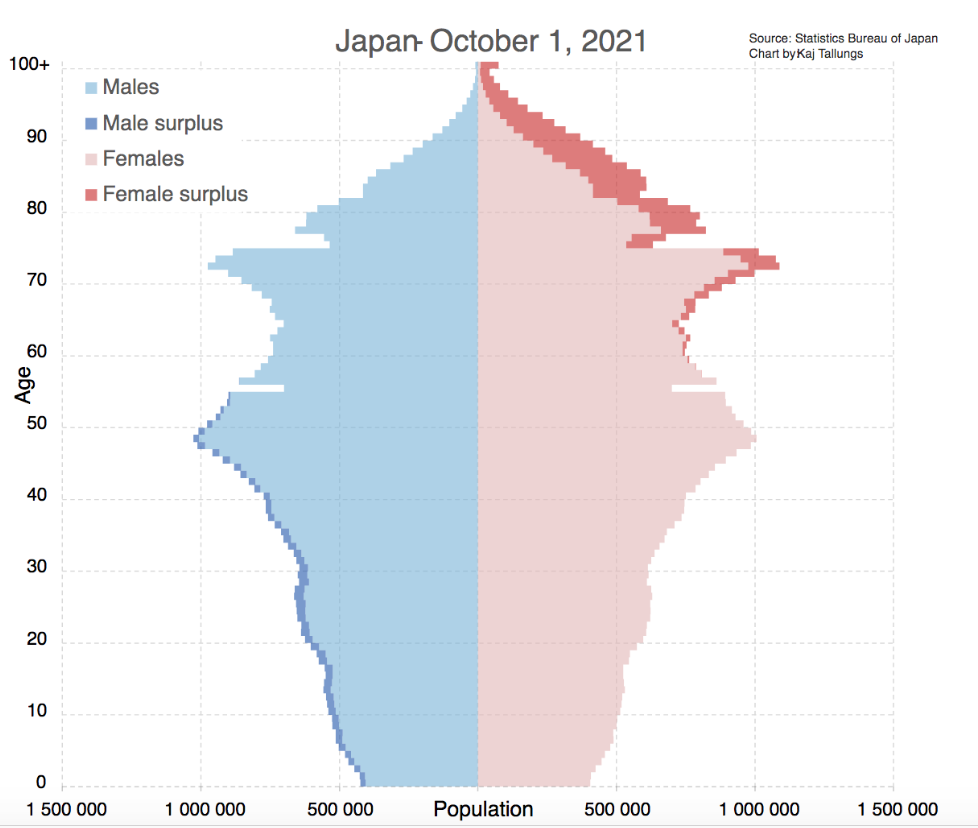

Japan’s population pyramid in October 2021. Kaj Tallungs. CC BY-SA 4.0

There are more and more elderly people in the country and not enough working-age adults to support them. The economy is at risk. But Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida promises to combat the low birth rate.

With Japan “standing on the verge of whether we can continue to function as a society,” Kishida urges the national government to focus on policies regarding children and ramp up child-related programs, saying it “cannot wait and cannot be postponed.” He wants the government to double its spending on child-related programs and in April, he will launch a new Children and Families government agency to help in the endeavor.

This agency will unify policies across multiple government ministries to better deal with issues that concern children, such as declining birth rates, child poverty, and sex crimes. Kishida has plans to double the budget if necessary, without elaborating.

In the mid 1990s, the Japanese government launched a series of programs addressing their country’s low fertility, hoping to provide parenting assistance through increasing provision of childcare services and advocating for a better work-life balance. And in the 2010s, fertility policies were incorporated into Japan’s macroeconomic policy, national land planning, and regional and local planning.

Despite all these efforts, however, Japan’s goal to boost population remains unsuccessful. By forming the new agency, Kishida hopes these problems will be taken more seriously.

One thing remains clear, though — Japan is facing a population crisis. And if birth rates keep falling, the country’s economy will struggle under its effects.

Michelle Tian

Michelle is a senior at Boston University, majoring in journalism and minoring in philosophy. Her parents are first-generation immigrants from China, so her love for different cultures and traveling came naturally at a young age. After graduation, she hopes to continue sharing important messages through her work.