Thousands of women were forced to work in “comfort stations” during World War II and their persistent fight for justice continues today.

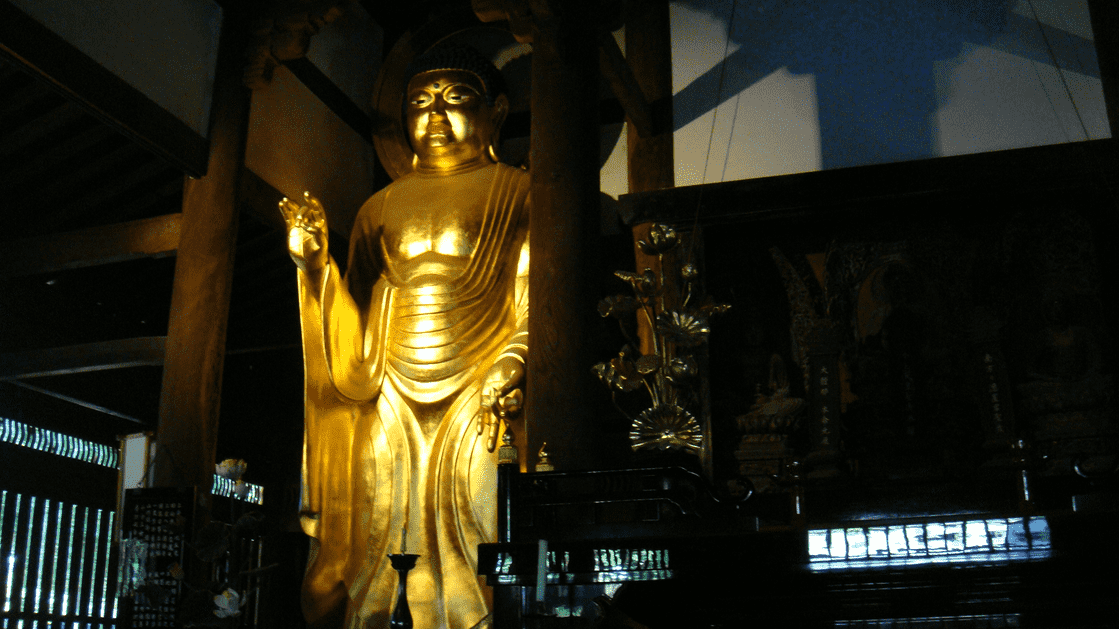

A statue commemorating the Korean victims of comfort stations. Hossam el-Hamalawy. CC BY 2.0.

During World War II, the Japanese Imperial Army kidnapped and coerced tens of thousands of women into sexual slavery, placing them into discreetly named “comfort stations.” Since then, the Japanese government has gone to great lengths to obscure this history, relenting to a few petitions for justice only conditionally. As the 80th anniversary of World War II’s conclusion approaches, some victims feel that further reparations are needed.

Between 1932 and 1945, some 400 “comfort stations” were set up for Japanese soldiers across Asia. The term “comfort station” was essentially a euphemism for brothel, established by Emperor Hirohito in an effort to prevent rape and sexual diseases and to preserve Japan’s global image. The number of stations expanded after the 1937 Nanjing Massacre, where the world was shocked to hear of the widespread sexual violence from Japan’s army. As such, these stations were presented as a tolerable alternative, with the women employed in them being participating sex workers. In reality, these operations were a lot more heinous.

The “employment” of these women and girls was overwhelmingly coercive and forceful in nature. Many of the victims from Korea struggled financially and were lured to comfort stations under the false pretenses of a better job. Others were threatened with violence and intimidated into the role. In colonies like Taiwan (Taiwan was a Japanese colony from 1895 to1945), they were explicitly forced into such labor while other women were forced to work in hospitals and kitchens. Once deployed, these women and girls were treated like military equipment, systematically shipped, administered and assaulted. They endured physical pain, sexual disease, pregnancy and brutal violence if they refused to comply.

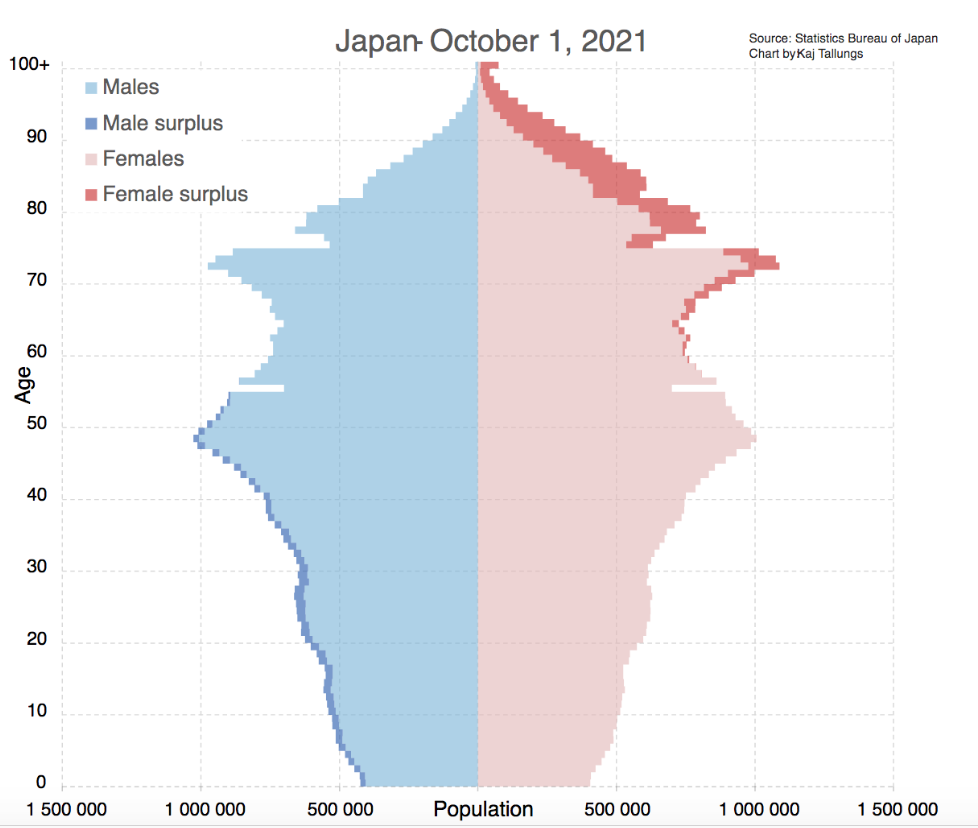

Given the effort to obscure this history, accurate statistical information is hard to find. No official survey or report was ever done to uncover exactly how many women and girls were implicated in the violence. Researchers estimate that the number could include up to 400,000 individuals, with the majority hailing from Korea and China. They also estimate that only around 10% of victims survived till the end of World War II.

For decades, the Japanese government denied that such “comfort stations” ever existed, destroying any official documents that remained. It wasn’t until the 1990s that the issue was widely acknowledged.

In 1991, victims began to come forward with their stories. They filed a class-action lawsuit against the Japanese government, demanding: a formal apology, reparations, official investigations into the crimes, revisions to school history textbooks and the construction of a memorial. The following year, a Japanese historian uncovered documents proving that the Imperial Army had in fact established and operated the alleged comfort stations. As a result, Prime Minister Miyazawa issued a formal apology and investigation in 1993.

Since then, a myriad of other testimonies, stories and lawsuits have come out. While Japan asserts that their reactions have been sufficient — pointing particularly to their 1993 apology and 2015 reparations agreement for Korean victims — a majority of survivors are not satisfied and have expressed distrust. As part of the 2015 agreement, for example, South Korean women had to promise not to publicly criticize the Japanese government. With Japan’s efforts appearing to hinge on a desire to obscure the past, the women instead seek a sincere apology and further remembrance.

The issue is still a point of contention, with Japan continuing attempts to conceal the details as families of victims issue further lawsuits. As the tension persists, it raises important questions about how to effectively memorialize the experiences of these victims and ensure that such history is never repeated.

Isabella Feraca

Isabella is a junior at Carnegie Mellon University studying professional writing and music technology. In her free time, she can be found reading, making music, and playing shows with her band around Pittsburgh.