Visiting a country during a cultural festival can be an amazing experience. Once travel resumes, plan a trip to one of these top festivals in Asia. From the Bali Kite Festival to the Desert Festival of Rajasthan, and learn of many more.

Read MoreComfort or Cruelty? The Buried Truth of Imperial Japan’s Sexual Slavery

Thousands of women were forced to work in “comfort stations” during World War II and their persistent fight for justice continues today.

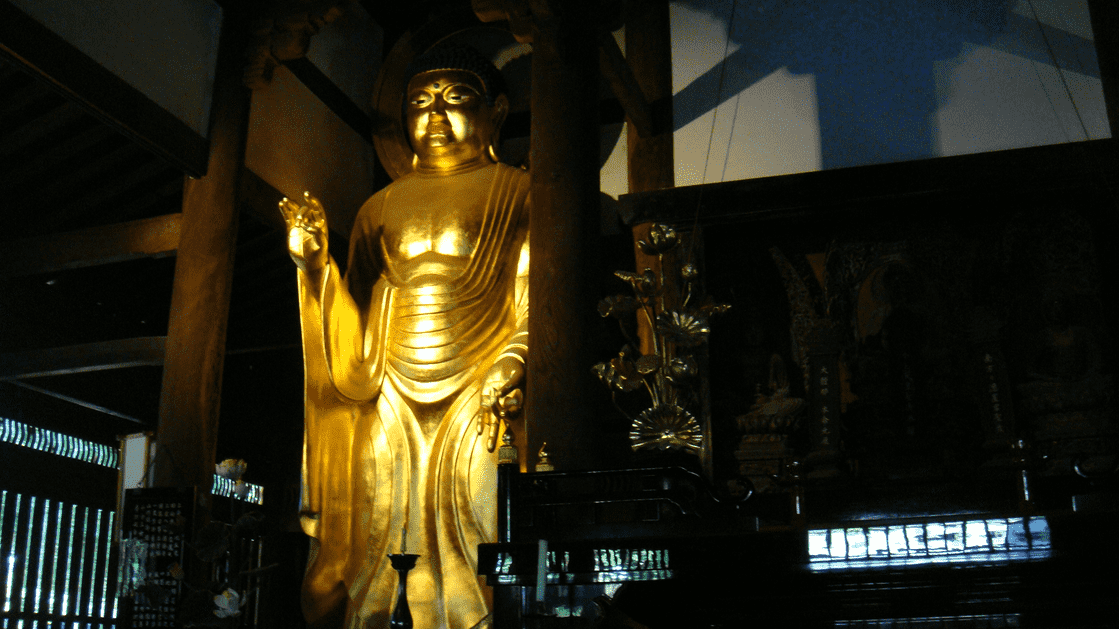

A statue commemorating the Korean victims of comfort stations. Hossam el-Hamalawy. CC BY 2.0.

During World War II, the Japanese Imperial Army kidnapped and coerced tens of thousands of women into sexual slavery, placing them into discreetly named “comfort stations.” Since then, the Japanese government has gone to great lengths to obscure this history, relenting to a few petitions for justice only conditionally. As the 80th anniversary of World War II’s conclusion approaches, some victims feel that further reparations are needed.

Between 1932 and 1945, some 400 “comfort stations” were set up for Japanese soldiers across Asia. The term “comfort station” was essentially a euphemism for brothel, established by Emperor Hirohito in an effort to prevent rape and sexual diseases and to preserve Japan’s global image. The number of stations expanded after the 1937 Nanjing Massacre, where the world was shocked to hear of the widespread sexual violence from Japan’s army. As such, these stations were presented as a tolerable alternative, with the women employed in them being participating sex workers. In reality, these operations were a lot more heinous.

The “employment” of these women and girls was overwhelmingly coercive and forceful in nature. Many of the victims from Korea struggled financially and were lured to comfort stations under the false pretenses of a better job. Others were threatened with violence and intimidated into the role. In colonies like Taiwan (Taiwan was a Japanese colony from 1895 to1945), they were explicitly forced into such labor while other women were forced to work in hospitals and kitchens. Once deployed, these women and girls were treated like military equipment, systematically shipped, administered and assaulted. They endured physical pain, sexual disease, pregnancy and brutal violence if they refused to comply.

Given the effort to obscure this history, accurate statistical information is hard to find. No official survey or report was ever done to uncover exactly how many women and girls were implicated in the violence. Researchers estimate that the number could include up to 400,000 individuals, with the majority hailing from Korea and China. They also estimate that only around 10% of victims survived till the end of World War II.

For decades, the Japanese government denied that such “comfort stations” ever existed, destroying any official documents that remained. It wasn’t until the 1990s that the issue was widely acknowledged.

In 1991, victims began to come forward with their stories. They filed a class-action lawsuit against the Japanese government, demanding: a formal apology, reparations, official investigations into the crimes, revisions to school history textbooks and the construction of a memorial. The following year, a Japanese historian uncovered documents proving that the Imperial Army had in fact established and operated the alleged comfort stations. As a result, Prime Minister Miyazawa issued a formal apology and investigation in 1993.

Since then, a myriad of other testimonies, stories and lawsuits have come out. While Japan asserts that their reactions have been sufficient — pointing particularly to their 1993 apology and 2015 reparations agreement for Korean victims — a majority of survivors are not satisfied and have expressed distrust. As part of the 2015 agreement, for example, South Korean women had to promise not to publicly criticize the Japanese government. With Japan’s efforts appearing to hinge on a desire to obscure the past, the women instead seek a sincere apology and further remembrance.

The issue is still a point of contention, with Japan continuing attempts to conceal the details as families of victims issue further lawsuits. As the tension persists, it raises important questions about how to effectively memorialize the experiences of these victims and ensure that such history is never repeated.

Isabella Feraca

Isabella is a junior at Carnegie Mellon University studying professional writing and music technology. In her free time, she can be found reading, making music, and playing shows with her band around Pittsburgh.

The Truth about Geisha Tourism in Japan

Japan’s geisha have survived war and the turn of the century — unruly travelers may be the dying art’s final blow.

A geisha-in-training looks out at Gion, Kyoto. Satoshi-K. CC BY 2.0

With her milky-white oshiroi, silky kimono and glossy bouffant, the geisha’s dramatic flair has left a lasting impression within the cultural imagination of Japan. Geisha, Japanese female entertainers, are regarded as icons of their country’s rich artistic heritage — it’s often said they exist in a sphere separate from the rest of us, in the dreamy, gossamer “flower and willow world.” However, from serving as factory workers during World War II to being popular (and controversial) visitor attractions today, there’s more than meets the eye to these revered performers, and they’ve come a long way from their medieval origins.

“Japanese women in reading and writing” by Katsukawa Shunshō. The New York Public Library. CC0

In Japanese, the word “geisha” literally translates to “art person.” Indeed, traces of the geisha tradition can be traced back as early as Japan’s Heian period in 794, when the country began to place a larger emphasis on poetry and beauty. This newfound appreciation for the fine arts set the aesthetic stage for the geisha’s forerunner, the courtesan, to come onto the scene. Courtesans were female performers well-versed in song, dance, conversation — and sex. Sex work proliferated throughout Japan as men illicitly sought connections outside of their wives, who were still held to Confucian ideals of virtue and modesty. In the 1600s, however, the ruling samurai outlawed prostitution to “clean up” Japanese society, confining sex work to “yūkaku,” or “pleasure houses.” But boxing courtesans out of mainstream society did not kill the industry — rather, consolidating these trained performers gave rise to a new, distinct culture of art and ceremony.

Yūkaku evolved into spaces of entertainment, with women increasingly making their trade in song, dance and music rather than sex. A former prostitute first called herself a “geisha” around 1750, and many women followed suit. It is important to note that although many (both consensually and nonconsensually partook in sexual exchanges, geisha were not sex workers then and are not today. Geisha instead focused on being entertaining hostesses and conversationalists for their upper-echelon clientele and adept in traditional arts like the tea ceremony, calligraphy and flower arranging.

The increasing popularity of geisha persisted well into the 19th century as the profession organized into a highly structured working class involving exclusive apprenticeships and patronages. Training started at a young age, as early as six years old (some children were sold by their parents to geisha houses or “okiya”). Girls spent years as “maiko,” or geisha-in-training, rigorously learning the traditional arts before making their debut. Old-fashioned courtesans declined in popularity as wealthy men increasingly found company in geisha, whose public perception became glamorized as a result. Until World War II.

Like nearly every aspect of Japanese life, the geisha industry was irreversibly changed by WWII. After leaving to aid in the war effort, many “maiko” did not return to their “okiya” after the war, instead choosing to remain in their industrial jobs. With the onset of WWII, becoming a geisha was no longer a girl’s only way out of poverty. Geisha dispersed, and the few that remained grew increasingly protective over their traditions. Some aspects of the trade changed — the training age was raised from six to 16, for example. But this general reclusion from Westernization and modernity contributed to geishas’ decline in the mid-20th century as men shifted their preference to other female entertainers like models and bar girls. But geisha remain popular among travelers, even receiving a popularity boost among Western audiences from Arthur Golding’s (in)famous 1998 novel “Memoirs of a Geisha.”

Two geisha with a businessman. Herb Gouldon. CC0

There are still dozens of geisha districts, or “hanamachi,” across Japan that travelers can visit to experience traditional geisha entertainment and hospitality. In Tokyo, travelers can sample sake and listen to a “samisen” performance, while in Niigata, they can watch “geigi” dancing. But recently, geisha have called out visitors for overstepping boundaries, citing predatory behavior ranging from unsolicited photography to sexual harassment. As a result, Japan’s geisha mecca, Gion, banned non-residents from parts of the region this past March.

“There will be a fine of 10,000 yen [$67 USD]” for nonresidents caught wandering Gion’s streets, Kyoto district official Isokazu Ota told the Associated Press. “Kyoto is not a theme park.”

As COVID precautions have been lifted over recent years, it’s as if people have forgotten how to act now that they can travel again. Several countries have reported instances of traveler misbehavior since easing travel restrictions. Some popular destinations have even implemented tourist bans of their own. However, Japan’s situation is unique as the misbehavior concerning geisha is rooted in a historic misconception laden with sexist undertones.

Geisha are not sex workers. This widespread misunderstanding largely originates from World War II, as men returned home and spoke of their dalliances with “geisha girls.” Given that geisha were and are prohibited from offering sexual services, these men were likely talking about prostitutes and not actual geisha. But by conflating geisha with sex workers, these men began a lasting hypersexualization of geisha, degrading the women and debasing their culture in one fell swoop. Although some geisha did have sexual relationships with their clientele — both by choice and coercion — the misconception that all geisha did so still persists. These lingering sentiments contribute to the harmful thinking and behavior seen today, with visitors believing that it’s okay to treat geisha like zoo animals because they exist to please others, specifically men.

In truth, there has been debate in recent years surrounding the sustainability of Japan’s geisha industry regarding its perceived incompatibility with feminist ideals. Some argue that geisha entertainment is contingent on the male gaze and that its business model is thus outdated and problematic.

“I had clients slip their hands through the side openings of my kimono to fondle my breasts, and when in private rooms they’d open the hems of my kimono so as to touch my crotch. ” ex-geisha Kiritaka Kiyoha wrote on X. “When I told the house mother about these incidents, she directed her anger at me, saying I was at fault.”

When considering their job description at face value, geisha are not inherently feminist. They wear intricate makeup, they learn art and conversation — all to please men. While there may be a self-empowerment aspect to it, they are ultimately catering to and capitalizing off of male interests. But therein lies the paradox: they are capitalizing. Geisha are some of Japan’s most financially independent women. Yes, perhaps this independence wouldn’t be possible without men there to buy their company, but geisha represent a distinctly female tradition of economic self-sufficiency, a feminist ideal some Western countries are still aspiring toward.

Of course, as Kiyoha reminds us, geisha being a time-tested practice doesn’t justify the predatory behavior that props it up: “I would like you to consider if [abuse and harassment] is truly what one would call traditional culture,” she continued on X.

Gion’s traveler restriction is intended to protect geisha and restore dignity to their traditions, but there’s also a fear that it will expedite what many view as the dwindling profession’s inevitable extinction. It’s estimated a mere 1,000 geisha are still practicing in Japan, a far cry from its pre-WWII peak of 80,000. This steady decline, coupled with the bans, leaves many wondering where geisha and their dying art go from here.

“I don’t want the geisha occupation to disappear,” Kiyoha said, but “the industry should rebuild, oriented in a better direction.”

Geisha walks through Kyoto. Tawatchai Prakobkit. CC BY 2.0

Geisha are enigmatic by design, and it is crucial that the public remain interested in the culture and history underlying their time-honored trade. But more than relics of a bygone era, geisha are cultural guardians, and they are people. If/when travel to geisha districts opens back up, it is important to remember that their shroud of mystery is not an invitation for travelers to poke and prod and investigate — there are ways to learn about the culture without violating these women’s boundaries.

Bella Liu

Bella is a student at UC Berkeley studying English, Media Studies and Journalism. When she’s not writing or working through the books on her nightstand, you can find her painting her nails red, taking digicam photos with her friends or yelling at the TV to make the Dodgers play better.

Matcha's Roots: The Legacy of Japan's First Tea Tree

Explore Shofuku-ji, Japan’s oldest Zen temple, where the legacy of the first tea tree still thrives.

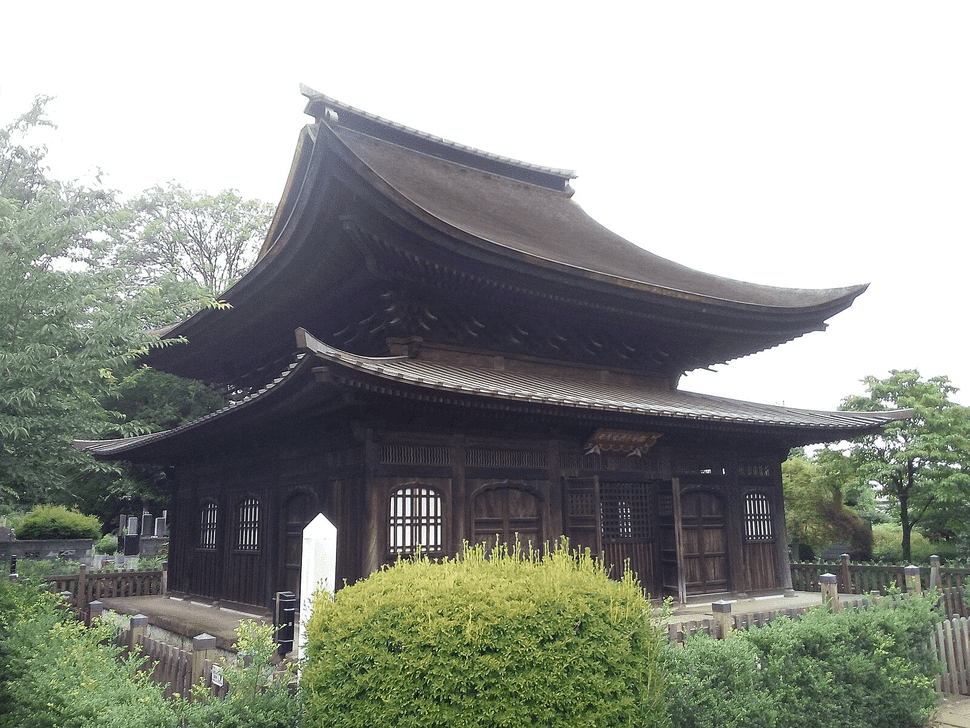

Shofuku-ji Temple. N yotarou. CC BY-SA 4.0

At the end of an unassuming street in Fukuoka, Japan stands the Shofuku-ji Temple. Its ancient grounds are a testament to centuries of cultural and spiritual history, particularly to the evolution of matcha, Japan’s iconic powdered green tea. Matcha is made from specially grown and processed tea leaves. The process begins with shading the tea plants several weeks before harvest to boost chlorophyll levels, resulting in its vibrant green color. The leaves are then carefully picked, steamed to stop oxidation, dried, and ground into a fine powder using traditional stone mills. Matcha's popularity outside Japan, especially in the U.S., experienced a surge in the early 21st century due to a growing interest in health and wellness globally. Its high antioxidant content, culinary versatility, and cultural appeal contributed to its widespread adoption in cafés and homes worldwide.

Shofuku-ji Temple was founded in 1195 CE by the Buddhist priest Myōan Eisai, who is often credited with introducing Zen Buddhism to Japan. However, Eisai’s cultural influence extends beyond religion. Chinese legend dates the invention of tea to around 2737 BCE in ancient China. From China, the beverage was brought to Japan by a mission of monks, including Eisai, returning from a pilgrimage in 1191 CE. Upon arriving in Japan, Eisai cultivated the tea seeds in the Iwakamibo gardens of Ryozen-ji Temple, Saga.

Shofuku-ji Temple Pond. Mark Pegrum. CC BY 2.0

These seeds, which produced the first tea plants in Japan, became the foundation of what is now known as matcha. The plant that stands at Shōouku-ji today, often referred to as "Japan’s First Tea Tree," is a direct descendant of those original plants, a living monument to the history of Japanese tea culture.

When Eisai brought the tea seeds to Japan, he was not merely bringing a new beverage, he was introducing a practice that would become integral to the Zen way of life. The preparation and consumption of matcha evolved into a ritualized practice that aligned perfectly with the principles of mindfulness and presence central to Zen.

Buddha Statue. David McKelvey. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Referred to as “the way of tea,” the preparation of tea developed into an exercise of Zen devotion that honored the beauty which can be discovered in an otherwise flawed world. Author and tea expert Solala Towler has said: “It is a ceremony that takes the simple art of drinking tea to a sacred level, where the host and the guests share a moment of worship of the simple art of preparing and drinking of tea together, elevating them to a level of purity and refinement.”

The Jizōdō at Shōfuku-ji. MomoyamaResearch. CC BY-SA 4.0

The word matcha comes from the Japanese verb “matsu”, (to rub or to daub) and “cha” , (tea). In its early form, matcha was consumed as a medicinal drink. Eisai himself wrote about the health properties of tea in his book “Kissa Yojoki” (“Drinking Tea for Health”), where he extolled the virtues of tea for both body and mind.

Eisai believed that tea could cure physical ailments and enhance mental clarity and spiritual well-being, making it an ideal companion for Zen meditation. He realized that drinking matcha improved his meditation sessions by producing a state of calm alertness, likely a product of the cognition-boosting interaction between matcha’s caffeine and L-theanine. Caffeine, a natural stimulant, provides an energy boost. However, caffeine alone can sometimes lead to jitters, increased heart rate, or anxiety. L-theanine, an amino acid found in tea leaves, counters this with its calming effect on the brain. It promotes the production of alpha waves, which are associated with a relaxed yet alert mental state.When consumed together in matcha, caffeine and L-theanine synergize to create a balanced effect.

Shofuku-ji Temple. David McKelvey. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

For centuries, the practice continued to spread throughout Japan, dispersing throughout all levels of society. Today, the matcha tea ceremony provides an opportunity for intellectual exchange, the sharing of knowledge and the continuity of tradition.

As was written in a collection of essays entitled “The Book of Tea” by Okakura Kakuzo, one of the first Japanese to advocate for the art of tea drinking, “Those who cannot feel the littleness of great things in themselves are apt to overlook the greatness of little things in others,” a sentiment that ties humility in oneself to the appreciation of others and their work, tea among them.

A Sanmon at Shofuku-ji Temple. STA3816. CC BY-SA 3.0

Today, Shofuku-ji Temple remains a serene sanctuary where visitors can connect with the historical and spiritual origins of matcha. The temple grounds, with their carefully maintained gardens and ancient structures (including a Buddhist temple, a kitchen, a Zen hall, a bell tower, a sun and moon garden, a records hall, and more) provide a peaceful setting for reflection upon the past. Visitors can appreciate the tea plant, a living link to Japan’s first tea plants, and the enduring legacy of Eisai’s contributions to Japanese culture.

Generally, Shofukuji Temple is not open to the public. If you are visiting as a group, you must apply one month in advance and receive permission from the temple, even if you just wish to tour the grounds. The application and a guide to the grounds can be found on the temple’s website. The temple is a nationally designated historic site that protects cultural assets and the continuation of the Zen tradition, so visitors are asked to proceed quietly and with care. Visitors may also be asked for a contribution to help protect and restore cultural properties. Applications received less than one month in advance will not be accepted.

GETTING THERE

Shofukuji Temple can be reached in a short walk from Gion Station and a 15-20 minute walk from Hakata Station in Fukuoka. Fukuoka is the sixth largest city in Japan and offers a variety of hotels and transportation methods for visitors.

Rebecca Pictairn

Rebecca studies Italian Language and Literature, Classical Civilizations, and English Writing at the University of Pittsburgh. She hopes to one day attain a PhD in Classical Archeology. She is passionate about feminism and climate justice. She enjoys reading, playing the lyre, and longboarding in her free time.

A Trip Through the Past: Japan’s Living Heritage on Sado Island

The historical music, performing arts and cuisine are kept alive on a tiny resort island off the Japanese coast.

A Noh performance onstage on Sado Island. Yoshiyuki Ito, CC BY-SA 3.0

Feudal Japanese history gave rise to one of the most fascinating cultures in the world. Decades of relative isolation on the islands of Japan allowed for a completely unique society to blossom, and the resulting art, music and performance is incredible to behold. Although the world has largely moved on from the 18th century, there are still small pockets of society that try to keep those cultures alive. And there is no better place to see Japan as it once was than on Sado Island.

Sado Island was not always beautiful. In the beginning, it was used as a prison colony for political exiles from nearby Japan. Around 1601, however, the territory's rulers discovered a massive vein of gold running through the island. This naturally led to a gold rush, which jump started the population of Sado. The mine lasted for over 400 years, closing at last in 1989. After this, the population began to decline, and now the island has gone from a mining hub to a lush resort.

Today, Sado is a massive cultural hotspot. Throughout history, Sado Island was a crucial trading base on the way to Osaka—this resulted in a huge number of cultures leaving their mark on the land over centuries. Ancient Buddhist shrines and feudal Japanese temples share space across the island, as architecture from all eras fills in the gaps.

The city of Shukunegi, for instance, has been around for over 400 years—it was constructed during the beginning of the Edo era in the 1600s. Many of the buildings were actually built from wood and stone brought by or recycled from the trading ships themselves. Many of these structures are still standing today, packed tightly together to form blocks of houses.

However, the heart of Sado’s cultural preservation comes in the form of its performing arts and music. Noh, a traditional style of Japanese theater, is typically performed in shrines, with the audience sitting outside around bonfires. The stages are open on three sides, with the back featuring a painted image of pine trees. The lead performer typically wears a mask, fashioned after the leading characters of the play (although they are also used to denote spirits and demons). There is nothing in the world quite like Noh, and Sado Island is one of the best places to watch these magnificent performances in person.

Another example of classic Japanese culture on Sado Island is onidaiko, which literally translates as “demon drumming”. These performances include masked dancers and the famous music of Japanese taiko drumming, which was traditionally used to ward off negative energy and spirits during rice harvests. Taiko is most prominent during the Earth Celebration, which takes place in the middle of August every year and lasts for three days of music, performances, and culture. The Sado Island Taiko Centre, where visitors can see taiko drumming year-round, is home to two of the biggest taiko drums in the world.

In addition to its vibrant culture and rich history, Sado Island is a simply gorgeous natural vista. It boasts over 170 miles of coastline, with everything from nearly 100-foot cliffs and volcanic rock walls to lovely beaches. The island is also home to a wide variety of rare plants and animals, including the toki, also called the crested ibis, an extremely rare bird that has become the unofficial mascot of Sado. Even if you’re more in the market for nature than culture, there’s an incredible amount of both to be found on Sado.

Sado has a large number of hotels all over the island, ranging in price from $99 to $500. The island is a wonderful travel destination year-round, but the best time to go is mid-August in order to catch the Earth Celebration.

Ryan Livingston

Ryan is a senior at The College of New Jersey, majoring in English and minoring in marketing. Since a young age, Ryan has been passionate about human rights and environmental action and uses his writing to educate wherever he can. He hopes to pursue a career in professional writing and spread his message even further.

A Festival of Flight: Explore Japan’s Hamamatsu Kite Festival

Join more than 1.5 million people in May to celebrate the Hamamatsu Kite Festival.

Kites flying during the Hamamatsu Kite Festival. Shizuoka Prefectural Tourism Association. CC BY-SA 2.1 JP

The origins of the Hamamatsu Kite Festival date back more than 450 years. In Japan, kites have been used for both practical and celebratory purposes for over 1,000 years. During the Edo era, kites were flown to celebrate the birth of a first-born son. This tradition then developed into the Hamamatsu Kite Festival where all children are celebrated.

At the beginning of May during Golden Week, Hamamatsu’s skies are filled with over 100 vibrant, traditional kites. The designs of the kites in the Hamamatsu Kite Festival symbolize children and traditions from each town in the district of Hamamatsu. The kite fliers then partake in an aerial battle, attempting to sever each other's kite strings.

As dusk falls, the festivities move from the beach to the city center where the streets come alive with dance and musical performances featuring bells and drums. The traditional music follows nearly 100 artfully decorated floats as they travel through the streets of Hamamatsu. The floats carry children in customary clothing and are pulled by cheering adults with lanterns and flags in hand.

Some floats are over 100 years old, and travelers can learn about their history at the plaza between the JR-Hamamatsu and Shin-Hamamatsu train stations where a few floats are displayed throughout the day. There are three parade routes, so for those hoping to see all the floats it is recommended that they choose a different route each night.

The location of the kite battles on the Pacific coastline allows travelers easy access to other nearby marvels, such as one of three of Japan’s major sand dunes. The Nakatajima Dunes, known as a famous hatching ground for loggerhead sea turtles, can be found near the kite battles, and are surrounded by coastal forests.

Not only home to its eponymous Kite Festival, the city of Hamamatsu is a destination known for its diverse landscapes and impeccable craftsmanship. Along with the coastline, Hamamatsu boasts mountains, a river and Lake Hamana, the birthplace of Japan’s eel-farming industry. Energetic travelers can participate in many activities at Lake Hamana, including windsurfing, swimming and biking.

Nature lovers will feel right at home among thousands of plant species at the Hamamatsu Flower Park. History buffs can learn about the city’s musical history at the Hamamatsu Museum and explore Hamamatsu Castle.

Hamamatsu is easily accessible from Tokyo. Travelers can take a bullet train from Tokyo Station to Hamamatsu Station in as little as 100 minutes.

Madison Paulus

Madison is a student at George Washington University studying international affairs, journalism, mass communication, and Arabic. Born and raised in Seattle, Washington, Madison grew up in a creative, open-minded environment. With passions for human rights and social justice, Madison uses her writing skills to educate and advocate. In the future, Madison hopes to pursue a career in science communication or travel journalism.

Japan’s Population Crisis Hits a Record Low

Japanese birth rates are falling exponentially, and it could have major effects on the country’s economy.

Harajuku District in Japan. @paulkrichards. Instagram

Many around the world consider Japan a futuristic country, a view drawn from its creative technology and its unique culture. A popular destination for tourists all around the world, this East Asian country makes up 1.6% of the world’s population with its approximately 125 million residents.

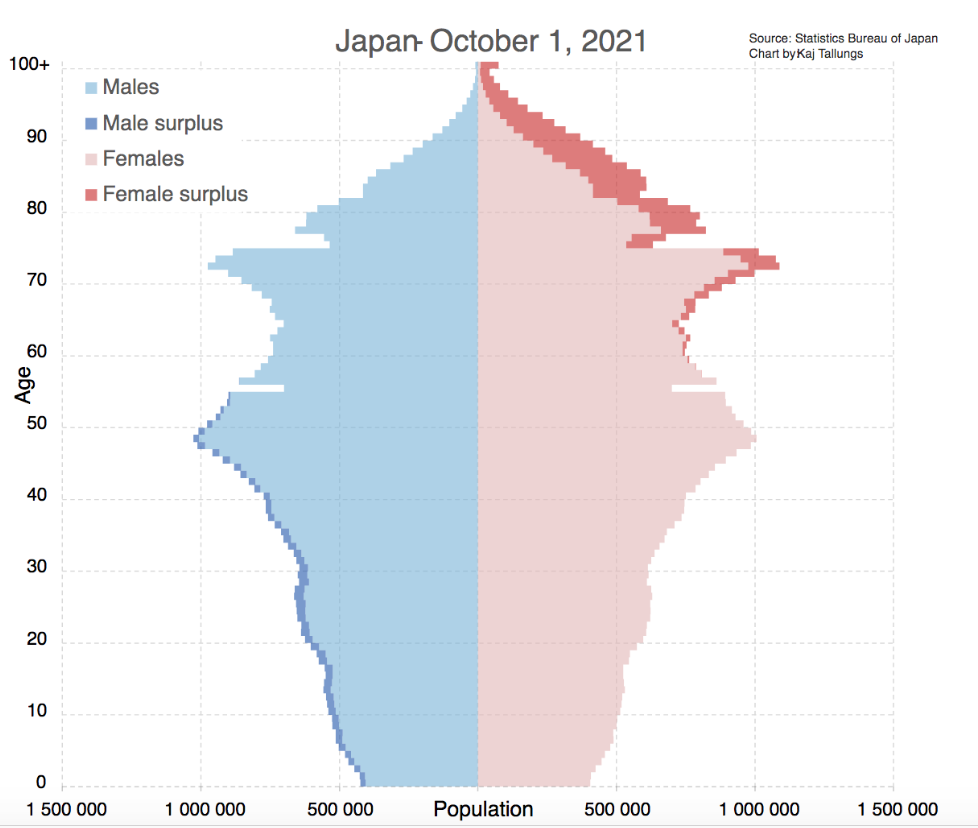

However, this number is set to rapidly decline as Japan teeters on the precipice of a population crisis. Its Prime Minister has issued a dire warning, saying that the country is “on the brink of not being able to maintain social functions” due to the falling birth rate. Japan has one of the highest life expectancies in the world, which means that most will grow old and require care from others, but the workforce is shrinking as aren’t enough young people to fill the gaps in Japan’s stagnating economy.

Why is this? To use simple terms, Japanese people are having fewer babies. Women are postponing their marriages and rejecting traditional paths to focus on their professional lives, and the percentage of women who work in Japan is now higher than ever. However, there are also fewer opportunities for young people, especially men, in the country’s economy. Since men are still widely viewed as the breadwinners of the family, a lack of good jobs would also mean the men would avoid having children — and settling down — knowing they can’t afford it. With Japan’s high cost of living, it adds more reason for couples to steer clear of having a family.

The problem has only gotten worse since the Covid pandemic. In 2021, the birth rates in Japan declined to around 805,000 — a figure that was not expected until 2028. With much of the population choosing to focus on their careers instead, this number will only continue to fall.

In the early stages of the pandemic, there were jokes circulating that the lockdowns would cause another baby boom. However, the opposite came true. Japan experienced a reduction in birth rates, as well as other countries such as Taiwan and China — to an estimated 1.07 children per woman.

Japan’s population pyramid in October 2021. Kaj Tallungs. CC BY-SA 4.0

There are more and more elderly people in the country and not enough working-age adults to support them. The economy is at risk. But Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida promises to combat the low birth rate.

With Japan “standing on the verge of whether we can continue to function as a society,” Kishida urges the national government to focus on policies regarding children and ramp up child-related programs, saying it “cannot wait and cannot be postponed.” He wants the government to double its spending on child-related programs and in April, he will launch a new Children and Families government agency to help in the endeavor.

This agency will unify policies across multiple government ministries to better deal with issues that concern children, such as declining birth rates, child poverty, and sex crimes. Kishida has plans to double the budget if necessary, without elaborating.

In the mid 1990s, the Japanese government launched a series of programs addressing their country’s low fertility, hoping to provide parenting assistance through increasing provision of childcare services and advocating for a better work-life balance. And in the 2010s, fertility policies were incorporated into Japan’s macroeconomic policy, national land planning, and regional and local planning.

Despite all these efforts, however, Japan’s goal to boost population remains unsuccessful. By forming the new agency, Kishida hopes these problems will be taken more seriously.

One thing remains clear, though — Japan is facing a population crisis. And if birth rates keep falling, the country’s economy will struggle under its effects.

Michelle Tian

Michelle is a senior at Boston University, majoring in journalism and minoring in philosophy. Her parents are first-generation immigrants from China, so her love for different cultures and traveling came naturally at a young age. After graduation, she hopes to continue sharing important messages through her work.

Why Japanese Fruit Is So Expensive

Japan places cultural importance on giving fruit gifts, leading to the cultivation of impressive fruits that can cost over $100

Square Watermelon. Joi Ito. CC BY 2.0.

In most parts of the world, fruit is a relatively common food, located in every grocery store and eaten as a healthy snack. However, fruit in Japan is expensive, much more than most would expect. Every piece of fruit is carefully grown and so much importance is placed on this that a single piece of fruit can cost over $200.

Of these expensive fruits, melons are the most famous. Many watermelons are grown in the shape of a cube, though known as square watermelons, and others a heart. Square watermelons were originally developed to make it easier to store them, but they are still watermelons. Yubari melons are also extremely costly, well-known for their sweetness, texture and aroma. They are known as the most expensive fruit because in 2010, a pair of them were sold for $45,000 to a melon-flavored mineral water company celebrating their 10th anniversary. Muscat grapes are also very popular, each one large, plump and shiny. However, the Ruby Roman grapes are even more special. These are grown only in Ishikawa, one of Japan’s prefectures, and a single one of these grapes can cost 2,500 yen (about $18). They are easily the most expensive grapes in the world, but they are also the largest, with each grape as big as a ping pong ball. Though these grapes are also classified into superior, special superior and premium, only 1-2 bunches of grapes are considered premium per year. In 2020, a premium group of Ruby Roman grapes sold for $12,000. Another popular and expensive fruit is the Japanese strawberry. Amao strawberries, grown in Fukuoka, cost around $7 per kilogram, but they are roughly 4-5 times the size of normal strawberries. Hatsukoi no kaori, or white jewel strawberries, are 3 times the size of a regular strawberry, but a singular one of them will cost $10. This is because of the unique color that they are famous for. Hatsukoi no kaori are white strawberries with red seeds, hence the name “white jewel”.

White Jewel Strawberry. Jed Schmidt. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

These impressive fruits are expensive for a reason. There is a lot of careful cultivation by the farmers who grow them so that the fruit turn out perfectly. Each farmer has their own way of meticulously taking care of their fruit plants. Some will pollinate each flower by hand, others have hats for their fruit in order to prevent sunburn and the rest will grow the plant so that each branch or vine only has one fruit. This way, all the nutrients in the plant are directed towards that particular fruit.

Display of Expensive Fruit. The Tronodon. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

In addition, fruit-giving is an important part of Japanese culture. The seasons play a large cultural role, and fruit represents them because different fruits thrive better during different times of the year. It allows people to experience and appreciate what each season has to offer, from the colors of the fruit, to their aroma and, of course, taste. Beyond that, since fruit is edible, it doesn’t clutter people’s houses. Also, since the fruit is a gift, it has to look perfect. They cannot have blemishes or other imperfections, which is why so much labor and dedication is devoted to growing each luxury fruit.

Katherine Lim

Katherine is an undergraduate student at Vassar College studying English literature and Italian. She loves both reading and writing, and she hopes to pursue both in the future. With a passion for travel and nature, she wants to experience more of the world and everything it has to offer.

Macaque Monkeys Attack in Yamaguchi, Japan

Macaque monkeys, previously peaceful residents of Yamaguchi, Japan, began targeted attacks in July.

Japanese macaque. Zweer de Bruin. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

The city of Yamaguchi, Japan boasts historic temples, invaluable art, stunning gardens and macaque monkeys. Macaque monkeys have lived in highly populated areas of Japan since as early as the 1600’s, and up until recently, Japanese macaques have had very few concerning interactions with people.

However, since July 8th, more than fifty people in Yamaguchi have been attacked by the monkeys. City officials and experts say nothing like this has ever happened, and they even initially thought it was only one crazed monkey committing all of the attacks. But even after the monkey in question was euthanized, the attacks continued, leading the city to realize that an entire band of monkeys had inexplicably started attacking humans after years of peaceful coexisting. Fortunately, as of late July, no serious injuries have occured, but city officials have taken to tranquilizing threatening macaques, as they are not deterred by food or traps.

What makes these unprecedented attacks even more puzzling is the fact that they seem very coordinated, with an explicit goal, even if that goal is unclear to the people of Yamaguchi. While minor injuries have resulted from the attacks, some of the attacks appear to be attempted kidnappings. Additionally, the monkeys began by targeting primarily young children and older women. While over the past few weeks they have begun attacking adult men as well, these demographics are so specific that it begs the question: what is their intent? Unfortunately, no one knows yet.

A mother in Yamaguchi recalls a monkey having broken into her home, and attempting to drag her child away. She noted that the monkey tried to take the child with it. The monkeys have been entering homes, and even lurking outside of nursery schools. While there have been occasional macaque attacks in the past, they primarily live in harmony with humans, and a planned effort like this is unprecedented.

Two Japanese macaques. Etsuko Naka. CC BY 2.0.

In terms of the history of Japanese macaques, as noted they have lived in Japan since as early as the 17th century. They are also incredibly intelligent animals, making the decision of the Yamaguchi officials to euthanize one a difficult call. Macaques have opposable thumbs and even sometimes walk on two legs. They are known for doing very human-like activities, such as bathing and relaxing in groups in hot springs in Japan. This habit, as well as the habit of washing their food in the ocean, was learned behaviors within the group, and previously, scientists thought only humans passed traditions and behaviors through generations.

Despite the monkey attacks, which will hopefully come to an end soon, Yamaguchi has many sites to visit and a fascinating history. It is known for its temples, such as the Rurikoji Temple and Joeiji Temple. It is also a coastal town known for having high quality seafood and sake, which is perfect for travelers interested in food. Additionally, Yamaguchi is a very historic area, as the city contributed to the overthrow of the feudal era in Japan in the late 1800’s.

Tokoji Temple in Yamaguchi, Japan. Yoshitaka Ando. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Ultimately, Yamaguchi, Japan is a beautiful and historic city which is currently experiencing turmoil at the hands of macaque monkeys. Officials hope that the situation will be resolved soon, and once it is, consider adding Yamaguchi to your travel list.

Calliana Leff

Calliana is currently an undergraduate student at Boston University majoring in English and minoring in psychology. She is passionate about sustainability and traveling in an ethical and respectful way. She hopes to continue her writing career and see more of the world after she graduates.

7 Famous Trees of The World

Today, trees face threats such as deforestation, habitat reduction and fires fueled by climate change. Despite it all, these seven tree species continue to symbolize the lands they call home.

Forest in Italy. Giuseppe Costanza. CC0 1.0

As urbanization and overpopulation fuel clearcutting around the globe, these trees stand in their own glory. Granted protection status, having festivals in their honor and attracting admirers from around the world, this is a list of trees that have made a name for themselves and their roots.

1. Baobabs, Madagascar

The Avenue of Baobabs. Zigomar. CC BY-SA 2.0

For many, the Avenue of Baobabs is the first thing that comes to mind when they hear the word "Madagascar." Approximately 50 baobab trees line the dusty road and surrounding groves between Morondava and Belon'i Tsiribihina. Endemic to the island, the trees are referred to as "renala," or "mother of the forest," by locals. The avenue has gained international fame, attracting crowds during sunset and became the first protected natural monument in Madagascar in 2007 when it was granted temporary protection status.

2. Yucca Trees of Joshua Tree State Park, California, USA

YuccaTree in Joshua Tree State Park.Esther Lee. CC BY 2.0

The yucca trees, for which California's Joshua Tree State Park was named, got the nickname “Joshua” from a band of Mormons traveling from Nebraska. The lunar desert climate is ideal for yuccas, which have grown adapted to storing water inside their trunks and twisted branches. They are said to be able to survive on very little rainfall a year, but if the weather happens to bring rain in the spring, the yuccas will give thanks with a sprout of flowers.

3. Cherry Blossoms, Japan

Cherry blossoms at Mount Fuji. Tanaka Juuyo. CC BY 2.0

The cherry blossom, or sakura, is considered the national flower of Japan. Hanami, the Japanese custom of enjoying the flowers, attracts locals and visitors to popular viewing spots across the country during the annual Cherry Blossom Festival. Peak bloom time depends on the weather, and the cherry trees have been flowering earlier and earlier each year due to climate change. On average, the cherry trees reach peak bloom in mid to late March and last around two weeks.

4. Jacaranda Trees, Mexico City, Mexico

Jacaranda trees. Tatters. CC BY-NC 2.0

Every spring, the already vibrant streets of Mexico City are lined with the jacaranda's violet bloom. President Álvaron Obregón commissioned Tatsumi Matsumoto, an imperial landscape architect from Japan, to plant the trees along the city's main avenues in 1920. Matsumoto was the first Japanese immigrant to come to Mexico, arriving a year before the first mass emigration in 1897 and staying until his death in 1955. Today the jacarandas are considered native flowers and symbolize international friendship.

5. Rubber Fig Trees, Meghalaya, India

Double-decker living roots bridge. Ashwin Kumar. CC BY-SA 2.0

Widely considered the wettest region in the world, villagers of the northeast Indian state of Meghalaya are separated by deep valleys and running rivers every monsoon season. The living roots bridges are handmade by the Khasi and Jaintia people with the aerial roots of rubber fig trees. The bridges grow strong as the tree's roots thicken with age, holding more than 50 people and lasting centuries if maintained. The double root bridge, pictured above, is almost 180 years old, stands at 2,400 feet high and suspends 30 meters in length.

6. Argan Trees, Morocco

Goats in an Argania tree. remilozach. CC0 1.0

Built to survive the Saharan climate, Argan trees are endemic to southwestern Morocco. Their scientific name, Argania, is derived from the native Berber language of Shilha (also known as Tashelhit). The trees grow fruits used to make argan oil, an ingredient found in many beauty products. Rights to collect the fruit are controlled by law and village traditions, while several women's co-operatives produce the oil. Goats are frequently photographed climbing argan trees and help in the production process by eating the nuts, leaving the vitamin-rich seeds for the locals to collect.

7. Trees of the Hoh Valley, Washington, USA

Trees in Hoh Valley. James Gaither. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

On the Pacific side of the Olympic Mountains in the Hoh Rainforest, lush yellow and green moss covers some of North America's giants, including the Sitka Spruce, Red Cedar, Big Leaf Maple and Douglas Fir. As a result of the area's average 140 inches of rainfall per year, the moss is not only enchanting but beneficial. Moss plays an essential role in supporting the forest's biodiversity; like a sponge, it decays, absorbs and finally releases nutrients for the trees’ roots to feed off.

Claire Redden

Claire is a freelance journalist from Chicago, where she received her Bachelor’s of Communications from the University of Illinois. While living and studying in Paris, Claire wrote for the magazine, Toute La Culture. As a freelancer she contributes to travel guides for the up and coming brand, Thalby. She plans to take her skills to London, where she’ll pursue her Master’s of Arts and Lifestyle Journalism at the University of Arts, London College of Communication.

Shohei Ohtani pitching in Sapporo. Scott Lin. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Baseball: A Japanese Pastime

America, over the years, has given a lot of cultural significance to the sport of baseball. We place it alongside apple pie and fireworks in the grand list of material symbols of our country. Not only that: baseball, over the years, has often reflected our country’s struggles back at us. It’s confronted discrimination in Jackie Robinson, and labor disputes with Curt Flood. It’s helped heal us, as well. Mike Piazza’s post-9/11 home run brought more joy to New York than anything that followed during the War on Terror.

But baseball is also of waning interest to many Americans. The sport is long, with games usually clocking in over three hours long. It also doesn’t market itself very well. Some of the greatest of all time are playing right now, but has any non-baseball fan heard of Mike Trout, Jacob DeGrom, or Shohei Ohtani? Likely not. The sport isn’t going away anytime soon, but there’s no doubt baseball’s cultural significance is declining in America. Fortunately, that isn’t the only place the sport is cherished.

Baseball was introduced to Japan during the late 1800s by way of an English professor from Maine named Horace Wilson. It didn’t take long for the sport to become a national pastime; professional leagues have existed since 1936, and the country’s national high school baseball championship, Summer Koshien, began in 1915. Today, baseball is Japan’s most popular sport; an almost bizarre outcome considering the existence of nationally-developed sports like sumo and globally adored sports like soccer.

But the popularity of baseball in Japan would be diminished if it weren’t for the homegrown players who have starred overseas. The first Japanese player to play in the MLB was a pitcher, Masanori “Mashi” Murakami, who debuted in 1964. Murakami wasn’t an elite player, and was even forced to return to Japan after two years due to his restrictive contract, but his appearance in the bigs opened the floodgates for others to make America’s game their own.

The first bona-fide Japanese star was pitcher Hideo Nomo. In 1995, Nomo’s first year in Major League Baseball, he posted a league-leading 11.1 strikeouts per nine innings to go alongside a 2.54 ERA (ERA stands for earned run average, or the average number of runs allowed every nine innings. Anything under 4 is considered good. Under 3? Great.) His rookie season is his best known (“Nomo fever” was said to have hit LA), but Nomo went on to have an excellent career, eventually retiring in 2008 after 323 games, 1918 strikeouts, and 2 no-hitters.

A fan holds a “Japan National Team” baseball flag at the World Baseball Classic. Steve Rhodes. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

There is also the case of Ichiro Suzuki, who with his illustrious career and unique style of play became one of the most well-loved baseball players of the 21st century. Ichiro had exceptional speed, stellar defense, and a superhuman ability to take care of his body, but he was best known for what he did with the bat in his hands. Ichiro’s approach was simple: he would slap the ball around the field, and beat out singles and doubles. He rarely walked or hit for power, but was so talented at this contact-oriented approach that it didn’t matter. It was primordial baseball planted firmly into the twenty-first century, and it worked. In 2004, Ichiro broke the single-season hit record, a record that had stood for 84 years and seemed all but unbreakable with how the game had changed. The principles of hitting have strayed from Ichiro’s even further since then; it’s not unlikely that Ichiro’s grand total of 262 hits in 2004 will stand until the earth is swallowed by the sun.

There’s only one active player who has a chance of topping Ichiro in the Japanese pantheon of stars, and his case is being made this very season. He’s a 27-year-old, currently having not just the best-ever season by a Japanese player, but possibly the best-ever season by anyone.

To explain Shohei Ohtani, one must first note that over its 150-year history professional baseball has become more and more a sport of specialization. Teams today might feature hitters who only hit against left-handed pitching, and speedsters who rarely start but are used late in games as pinch runners.

Ohtani is the one man who breaks up modern baseball’s prime order. He is a pitcher who hits; it’s as simple as that, really. Baseball players have long been separated into hitters and pitchers. Hitters don’t pitch (not seriously, anyway), and pitchers don’t hit (at least, not well; perhaps the best example of baseball’s specialist tendencies is how pitchers haven’t cared about being able to hit for a hundred years, despite the fact that half of the league still requires them to on a regular basis). But Ohtani plays both roles.

That in itself is historic. No player has been both a MLB pitcher and a lineup regular since Babe Ruth, who served the role in 1919. But here’s the kicker—Ohtani is really, really good at both his positions. He has hit 44 home runs while pitching to a 9-2 recond and a 3.36 ERA so far this season. Those are elite statistics, better than Ruth’s 1919 numbers. The value of one man bringing a season of premier pitching and hitting to his team is hard to quantify. But the case can be made that Ohtani’s 2021 season is the greatest of all time, at least so far. There’s no doubt the man is a one-in-a-million player, a gift from the baseball heavens. By coming from Japan, he also represents a nation that may lead in taking the sport forward.

This year, Japan beat the United States to win the gold medal in Olympic baseball. The victory, though marred by the fact that the best players from both countries stayed home, represented another step up the baseball ladder for Japan. As baseball exits America’s zeitgeist, it continues to grow in the island nation. The NPB’s level of play is going up—it’s still behind the major leagues, but not by a massive amount. Even more important is fan interest. In 2019, the last full season of the NPB, the league’s total attendance numbers grew to second in the world across all professional sports leagues.

As more stars are born and made, Japan’s baseball legacy will only continue to grow. Who knows? Maybe in a century, Japan will have come so far that baseball fans will diminish the careers of MLB stars like Trout, DeGrom, and Ohtani. They can’t be that good, the fans will say. They were playing in the United States.

Finn Hartnett

Finn grew up in New York City and is now a first-year at the University of Chicago. In addition to writing for CATALYST, he serves as a reporter for the Chicago Maroon. He spends his free time watching soccer and petting his cat.

Beyond Ice Cream, 7 Frozen Treats From Around the Globe

Ice cream is an ancient dessert, dating back to the second century B.C.. Since that time, countries around the world have developed their own versions of ice cream, from Indian kulfi to Ecuadorian Helado de paila.

Turkish dondurma is often served on a plate. tuhfe. CC BY 2.0

Ice cream is one of the most popular desserts in the United States. 6.4 billion pounds of ice cream were produced in the US in 2019 alone., The International Dairy Foods Association reports that, on average, each American consumes over 22 pounds of ice cream and other frozen desserts annually. But ice cream is not an American invention. The frozen dessert dates back to the second century B.C., when records show that leaders like Alexander the Great enjoyed ice and snow flavored with honey or nectar as a delicacy. Ice cream as we know it today likely derives from a recipe collected from the Far East by Italian explorer Marco Polo in the 16th century.

The ancient confection made from snow or ice flavored with honey, nectar, or fruit is present in historical records from around the world. While in England and America this treat evolved into the milk and cream based ice cream which we know today, other countries developed different versions of frozen desserts. Here are 7 frozen treats from around the globe, all impacted by the cultures that created them.

1. Dondurma, Turkey

Dondurma—the Turkish word for “freezing,” and sometimes referred to as Turkish ice cream—is often eaten with a knife and fork. Dondurma differs from American ice cream in several ways, the most obvious being the texture. While American ice cream is soft and creamy, dondurma is stretchy, chewy and does not melt easily, hence why it is most often served on a plate with a knife and fork. Dondurma is made from a milk and sugar base and added Arab gum, or mastic, a resin that gives the ice cream its chewiness. In addition to mastic, dondurma is thickened with salep, a flour made from the root of a purple orchid which grows in the mountains. The creation of dondurma is credited to the town of Kahramanmaraş, located at the foot of the Ahir Mountain in southern Turkey. The town has been producing dondurma for over 150 years, but the origins of the treat date back even further. Over 300 years ago, the people of the area mixed clean snow from the mountain with molasses and fruit extracts, creating an early form of ice cream. Today, dondurma is frequently served sprinkled with pistachios and can be found at restaurants as well as street vendors, where it is served in cones.

Colorful mochi ice cream. jpellgen (@1179_jp). CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

2. Mochi Ice Cream, Japan

Traditionally a dessert sold and eaten during the Japanese New Year, mochi has recently soared in popularity, especially in the United States. The term mochi refers to a unique Japanese delicacy dating back to 794 A.D., which is made from sticky rice dough. In Japan, mochi is most often enjoyed in small, round balls filled with red bean paste—a treat known as daifuku. In ancient times, mochi was made to be presented as an offering to the gods at temples and was also served to the Emperor and other nobility. Although mochi itself has been around for centuries, mochi ice cream was not developed until the 1980s. And, despite its Japanese roots, mochi ice cream is actually an American invention. It was created by Frances Hashimoto and her husband, Joel Friedman, who ran a Japanese-American bakery in Los Angeles during the 1980s. During a trip to Japan, the couple was inspired by the traditional daifuku to create their own mochi treat using ice cream. Today, mochi ice cream is sold at almost all major grocery stores and is available in a wide variety of flavors, like green tea, chocolate, mango and red bean.

Chocolate, Kesar, and Mango flavored kulfi. richardclyborne. CC BY 2.0

3. Kulfi, India

While often categorized as an Indian ice cream dish, kulfi is denser and creamier than ice cream, more closely resembling frozen custard. Kulfi is made from boiling milk until it solidifies, which is called khoa. Sugar is then added to the milk and the mixture is flavored as desired, typically using natural flavoring ingredients. Popular kulfi flavors include saffron, pistachio, mango, avocado and cardamom. After the kulfi mixture is flavored, it is poured into molds and frozen until the treat has set. Kulfi is thought to have originated in northern India during the 16th century Mughal Empire. Traditional desserts in that area already included condensed milk, and the Mughals added pistachios and saffron for flavoring and then froze the mixture in metal cones using a combination of ice and salt, giving rise to the kulfi dessert served today. Kulfi is popular not only in India but in Bangladesh, Myanmar, Pakistan and the Middle East as well. The dish can also be found in many Indian restaurants around the world.

Different flavors of Italian gelato. arsheffield. CC BY-NC 2.0

4. Gelato, Italy

Gelato is an Italian delicacy which differs from traditional American ice cream in its silky, creamy texture, as well as being denser. Gelato and American ice cream both contain milk and cream, but authentic gelato uses more milk than cream and does not usually contain egg yolks, which are a common ingredient in many ice creams. Gelato typically contains less butterfat as well, which makes the flavors more intense. It is also served at a temperature 10-15 degrees warmer than ice cream, so it melts more easily in one’s mouth. Modern gelato dates back to the Renaissance when Cosimo Rugierri, an alchemist, created a dessert from fruit, sugar and ice that delighted the powerful Medici family in Florence. Other accounts of modern gelato credit architect Bernardo Buontalenti, who is said to have prepared an ice cream dish from milk, egg yolks, wine, fruit and honey and served it to King Charles V of Spain. Whatever its origins, gelato quickly spread out of Italy, becoming a delicacy in other countries as well. Until 1686, however, gelato was mainly served in private residences of the wealthy, as ice and salt were expensive. Then, Italian Francesco Procopio Cutò opened a cafe in Paris where he sold gelato to the public. Since then, gelato has become a wildly popular treat that can be found on nearly every street in Italy and in restaurants and shops around the world.

5. Helado de paila, Ecuador

Helado de paila, literally “ice cream from a pot,” is a sorbet-like treat from Ibarra, Ecuador. The story goes that, 122 years ago in Ibarra, a teenage girl named Rosalía Suárez had nothing to give her friend as a 15th birthday gift. So, she decided to make her a dessert. Rosalía and a friend put natural fruit juice in a container and placed it on a wooden tray, where the container was surrounded by ice and straw to preserve it. They began to spin the container and beat the fruit juice, which turned into a form of ice cream. Rosalía perfected her recipe by adding sugar to the fruit juice and salt to the ice and began to sell her ice creams. Today, helados de paila are prepared in a way very similar to the technique that Rosalía Suárez first used. A blend of fruit and sugar is poured into a wooden bowl sitting in a larger bowl, or paila, which is already prepared with a layer of straw and a layer of ice and salt. The fruit mixture is stirred and eventually cools into the creamy helado de paila. Popular flavors include strawberry, blackberry, coconut, tree tomato and passionfruit.

Spaghettieis is made to look like a bowl of spaghetti. Joshua Shapiro. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

6. Spaghettieis, Germany

This popular German sundae is made from vanilla gelato, strawberry sauce and white chocolate shavings. The dish sounds innocuous enough, but what makes this treat unique is its presentation: the sundae is made to look just like a bowl of spaghetti. Spaghettieis was invented in 1969 by Dario Fontanella, whose father had moved from Northern Italy to Mannheim, Germany, in the 1930s. In an attempt to honor his Italian roots at the German ice cream parlor his family owned, Fontanella decided to create a bowl of spaghetti entirely from ice cream. Spaghettieis is made by putting vanilla gelato through a chilled spaetzle press (a machine to make German egg noodles) to achieve the spaghetti-noodle shape. The gelato is then topped with strawberry sauce to mimic tomato sauce, and shaved white chocolate curls to mimic parmesan. Apparently, when spaghettieis first began being served at ice cream parlors, it made children cry in disappointment that they were being served pasta rather than a dessert. Despite its tearful start, the dessert is widely popular today. Fontanella never patented his creation, so a variation of spaghettieis is served at nearly every ice cream parlor in Germany.

7. Akutaq, Alaska

Named after the Inupiaq word for “to stir,” Akutaq is an Indigenous Alaskan treat made by mixing fat, oil, berries and sometimes water or fresh snow together into a sweet dessert with a whipped texture. While berry-based akutaq is more similar to an American sorbet, there are also meat-based akutaqs in which the fat and oil are mixed with ground caribou or dried fish to create a more salty, gamey and savory dish. Traditionally in indigenous communities, the dish was made by women after the first catch of a polar bear or seal, and shared with members of the community. Akutaq varies by region depending on what types of flora and fauna are available to add. Indigenous people near the Alaskan coast used saltwater fish, while those inland used freshwater fish, and those in the north used bigger game like caribou, bear and musk-ox. Indigenous Alaskans have been making akutaq for thousands of years. Up until the 20th century, indigenous Alaskans held akutaq cooking contests during annual trade fairs, where members of various communities would compete to create new flavors. While akutaq can still be found today, in modern recipes the traditional caribou fat and seal oil are often replaced with Crisco and olive oil.

Rachel Lynch

Rachel is a student at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY currently taking a semester off. She plans to study Writing and Child Development. Rachel loves to travel and is inspired by the places she’s been and everywhere she wants to go. She hopes to educate people on social justice issues and the history and culture of travel destinations through her writing.

Amid Pandemic, Japan Faces an Epidemic of Loneliness

Japan has a Minister of Loneliness to address skyrocketing rates of suicide and isolation, some stemming from COVID-19 among other reasons. The elderly and hikikomori, modern day hermits, seem most affected.

Read MoreA tunnelbana train in Stockholm. Tony Webster. CC BY 2.0.

10 Metro Systems Around the World to Ride in Your Lifetime

Metro systems exist on every inhabited continent on the planet, being as unique in comparison to one another as are the diverse cultures and communities they serve. Some are highly efficient at moving people from point A to point B, others are rooted in the history of the local community and a few even serve as living art galleries that are ever-expanding. Here is our guide to the 10 must-visit metro systems to ride on in your lifetime.

1. Tunnelbana, Stockholm, Sweden

Serving 100 stations throughout the region, Stockholm’s Tunnelbana, which translates to “tunnel railroad,” is one of the newer metro systems in Europe, opening its first line in 1950. What makes the Tunnelbana unique is that it is considered to be the world’s longest art gallery, featuring an extensive collection of art made by over 150 artists.

2. Buenos Aires Underground, Argentina

The Buenos Aires Underground, known locally as Subte, is the oldest underground railway system in the Southern Hemisphere, dating back to 1913. The system hones in on its historic origins by providing both historic and modern train cars and stations which are spread out across its seven lines.

3. Seoul Metropolitan Subway, South Korea

Featuring 22 lines spread across 728 stations that serve both the heart of the city and rural communities, the Seoul Metropolitan Subway is one of the longest systems in the world. Opening its doors in 1974, Seoul's subway continues to grow, with several line extensions slated to open throughout the decade.

The iconic London Underground sign in front of Big Ben. Defence Images. CC BY-NC 2.0.

4. London Underground, UK

The oldest underground railway in the world, the London Underground began operation in 1863 and has since grown to serve 270 stations. Known in London as “the Tube,” the metro system provides easy access to neighborhoods throughout Central and Greater London, as well as connections to a slew of airports and other transit systems.

A Berlin U-Bahn train in a station. Michael Day. CC BY 2.0.

5. Berlin U-Bahn, Germany

Famous for its eye-catching yellow trains, the Berlin U-Bahn is one of the oldest and largest metro systems in Europe. The system had been partly severed in two parts during the Cold War due to the divide between East and West Berlin. Today it boasts 10 lines serving 173 stations, with an annual ridership of around 553.1 million.

A graffitied metro car in Athens passes in front of the Acropolis. Tim Adams. CC BY 2.0.

6. Athens Metro, Greece

Like Stockholm’s Tunnelbana, the Athens Metro serves as both a rapid transportation system and an extensive museum. In the system’s Syntagma Metro Station is a handful of the nearly 30,000 artifacts from the classical Greek, Byzantine and Roman periods which were excavated during the construction of new system lines in the 1990s.

Two trains in Tokyo pass over one another. David Gubler. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

7. Tokyo Metro, Japan

Offering seamless transitions between its stations and those of its counterpart, the Toei Subway, the Tokyo Metro is considered by many to be one of the best metro systems in the world for both convenience and cleanliness. Serving 180 stations across 9 lines, the Tokyo Metro has continued to expand as the city has grown to be the largest by population in the world.

An MTR train in Hong Kong. David Leo Veksler. CC BY 2.0.

8. Mass Transit Railway, Hong Kong

The Mass Transit Railway is a heavily-riden transit system serving Hong Kong Island, Kowloon and the New Territories, with a daily ridership of over 4.9 million. The transit system has a world-renowned reputation for being clean, affordable and reliable, as well as for offering free WiFi at all of the system’s stations.

The lights of a Paris Metro train passing over a bridge. Luc Mercelis. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

9. Paris Metro, France

The Paris Metro is a cultural landmark of the city, with stations highlighting the unique Art Nouveau architecture style. It is one of the densest metro systems in the world, consisting of 136 miles of track connecting 304 stations . The Paris Metro is also one of the busiest, being the second most traveled in Europe and tenth in the world.

A Soviet-era metro station in Moscow. Tarnya Hall. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

10. Moscow Metro, Russia

An extensive metro system with stations highlighting Cold War-era architecture, the Moscow Metro is the busiest system in Europe, serving 2.5 billion riders annually. The system has 241 stations and has connections to other transit systems like the Moscow Central Circle, Moscow Central Diameters and Moscow Monorail.

Jacob Sutherland

Jacob is a recent graduate from the University of California San Diego where he majored in Political Science and minored in Spanish Language Studies. He previously served as the News Editor for The UCSD Guardian, and hopes to shed light on social justice issues in his work.

5 Famous Japanese Flowers and Their Cultural Significance

Japan is home to many incredible feats of nature, but arguably one of the most beautiful parts of Japan’s landscape is its flowers—many of which can only be found in Japan.

Sakura and Mt. Fuji. Skyseeker. CC BY 2.0.

Flowers are national symbols of Japan. They represent specific emotions or sentiments and are often given as gifts to express unspoken feelings. In Japan, flowers communicate emotions in place of words; the Japanese “say it with flowers.” The Japanese proverb, “Iwanu ga hana 言わぬが花,” literally translates as “not speaking is the flower.” It means that some things are better left unsaid. This language of flowers is called “Hanakotoba,” with each flower conveying a very specific meaning and sentiment in Japanese culture. This tradition stems from Japan’s strong ties to Buddhism, which teaches the value of appreciating the present moment and connecting with nature. Below are five famous and culturally important Japanese flowers.

Lacecap Hydrangea. Ali Eminov. CC BY-NC 2.0.

1. Lacecap Hydrangea

Hydrangea macrophylla is a species of flower in the Hydrangeaceae family, native to Japan. There are many components to this plant, but they all come together to form one beautiful flower. The flowers are white and purple with four wide petals and small blue bulbs in the center—a feature of regular hydrangeas. In the middle of these flowers is a bunch of smaller blooms in shades of blue, purple and green. The flowers on the outside grow into large petals, while the bunch in the center remains as smaller flowers and buds. The Japanese name for this flower is Gaku, meaning “frame,” and representing the formation of the flower. In Hanakotoba, hydrangeas represent pride; this flower is gifted to someone the giver is proud of.

A red-veined cardiocrinum cordatum flower. Peganum. CC BY-SA 2.0.

2. Cardiocrinum cordatum

Cardiocrinum cordatum is a species of flowers in the lily family that is native to Japan and specific Russian islands. This flower resembles a lily, but its leaves are different in that they are shaped like a heart. The pale green flower blooms to the side, and is often used ornamentally due to its large, showy leaves. In Hanakotoba, white lilies represent purity and chastity.

Ranunculus japonicus flowers. Greg Peterson. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

3. Ranunculus japonicus

Also known as the Japanese Buttercup, this flower is a perennial from the family Ranunculaceae and is of Chinese and Japanese origin. Mainly growing in mountains and fields from Hokkaido to Okinawa, the Japanese Buttercup is an abundant, wild grass. In terms of appearance, these flowers are a bright yellow, with five rounded petals and a ring of yellow fringe around the small green bulbs in the center. According to the Japanese meaning, its leaves resemble horse hoofprints in the grass. Although very small, these flowers are bright and bring happiness to those who see them.

Japanese Apricot (Plum Blossom). Toshihiro Gamo. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

4. Prunus mume

Also known as Ume or Japanese apricot, these blossoms are from an East Asian and Southeast Asian tree species in the Armeniaca section of the genus Prunus (plums). They grow on the branches of the Japanese apricot tree and are incredibly fragrant with the smell of sweet honey. These flowers are also edible and make for stunning houseplants with their beautiful color and texture. The blossom’s buds are a dark pink, but they eventually bloom into a light pink when fully grown. In Japanese culture, this plant represents elegance, faithfulness and pure heart.

Camellia sasanqua, a November treat. Vicki DeLoach. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

5. Camellia sasanqua

Sasanqua is a species of Camellia native to both China and Japan, although it mostly grows in southern Shikoku, Kyushu and farther islands such as Okinawa. These bright pink and red flowers wilt one petal at a time, blooming from the end of autumn into the winter. In Hanakotoba, these flowers signify being in love or perishing with grace. Symbolizing the union between two lovers in the Chinese meaning, the delicate camellia petals represent the woman while the green leaves on the stem represent the man who protects her. The two components join together, even after death.

RELATED CONTENT:

VIDEO: Savor Japan’s Deep-Fried Maple Leaves

VIDEO: Bloom: Japan

VIDEO: Enter Kenya’s Rose Oasis

Isabelle Durso

Isabelle is an undergraduate student at Boston University currently on campus in Boston. She is double majoring in Journalism and Film & Television, and she is interested in being a travel writer and writing human-interest stories around the world. Isabelle loves to explore and experience new cultures, and she hopes to share other people's stories through her writing. In the future, she intends to keep writing journalistic articles as well as creative screenplays.

The departures board at the TWA Flight Center in New York. Wally Gobetz. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Stuck at Home? Try These 5 Virtual Travel Experiences

With uncertainty surrounding the pandemic’s end, many sustainable travelers are unsure of when they will be able to venture back out into the world. Sustainable travel is rooted in the idea that one’s trip leaves a positive impact on the community visited, and the risk of spreading COVID-19 to remote communities around the globe directly interferes with this principle.

However, many sustainability and social action travel companies have pivoted from in-person travel to offer a variety of virtual experiences which connect travelers with communities they would otherwise be unable to visit. Likewise, a number of tourism organizations, tech developers and travel lovers have created their own virtual travel offerings. This allows communities around the globe which have traditionally been reliant on tourism to maintain economic sustainability during this period of uncertainty. Here is our guide to five organized virtual travel experiences that you can do from the comfort of your home.

1. Learn to Prepare Mexican Salsas with ExplorEquity

A variety of salsas. Chasing Donguri. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Salsa is synonymous with Mexican cuisine. The delicious topping for chips, tortillas, tacos, burritos and enchiladas can trace its origins back to the Aztec, Mayan and Incan empires. Later popularized in Mexico and the United States throughout the 20th century, the salsa we know today can be made from combining an endless variety of ingredients. Given the regionality of Mexico’s cuisine, the country continues to innovate the popular dish in local restaurants, cafes, bars and homes.

With this unique virtual experience from ExplorEquity, travelers will learn to make a green creamy salsa, a red molcajete salsa and salsa macha. Led by chef Natalia from Mexico City, this virtual experience is perfect for salsa amateurs and connoisseurs alike. Each of the three recipes yields two servings, making this the perfect class to take with friends and family. ExploreEquity’s “Learn to Cook Mexican Salsa” class costs $39 per person and is generally offered every few weeks.

2. Practice Yoga in Sri Lanka, India and Portugal with Soul & Surf

A person practicing yoga on a beach in India. Dennis Yang. CC BY 2.0.

The origins of yoga date back thousands of years, but the practice is most commonly associated with Hinduism as one of its six orthodox philosophical systems. While still commonly associated with India, which is home to the world’s largest Hindu population, yoga over the past few decades has gained worldwide popularity for its physical benefits and meditative and spiritual components.

Soul & Surf, a wellness travel company operating in India, Sri Lanka and Portugal, offers travelers at home a unique opportunity to practice yoga with teachers from around the globe. Unlike other virtual yoga opportunities which generally consist of an archive of prerecorded sessions, Soul & Surf’s at-home yoga experience involves videos that are created and uploaded on a weekly basis, allowing travelers at home to connect with their teachers and destinations around the globe. Soul & Surf’s at-home offerings are continuous, and are sold as subscriptions for around $33 a month.

3. Break Bread with a Faraway Family Through Two Point Four

A family sharing a meal in Mozambique. WorldFish. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

One of the biggest casualties of sustainable travel throughout the pandemic has been the ability to connect with communities around the globe on a one-on-one basis. These intimate connections help to build lasting relationships, provide an opportunity for a mutual sharing of cultures, and foster a greater understanding and appreciation for the depth and complexity of the global community.

Two Point Four, a family-focused experiential travel company, has created a solution to allow intimate global connections to be made without risk of the virus’s spread. Through a free survey, the company will connect family travelers with others around the globe to facilitate community-building. Using a series of group calls, travelers will be able to learn from local guides and travel experts, break bread with other families, and allow folks to support one another on the issues of travel, sustainability and curiosity as the pandemic continues. What you do on the call is entirely up to you and the folks on the other end of the line—feel free to share favorite travel stories, have a meal together or discuss your lived experiences. The calls are free and vary in length based on the availability of the traveler and the other family or travel expert.

4. Explore the Natural Beauty of Chile with Chile 360

Amalia Glacier, Chile. Phil Parsons. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Chile is one of the most beautiful countries in the world. The 2,653 mile ribbon-shaped country, which hugs the western edge of Argentina, is home to countless climates and cultures, offering travelers to the country a unique experience. Visitors can wander the Atacama in the north, the world’s driest desert, or the fjords and glaciers common throughout Chile’s southernmost regions. Santiago, the nation’s capital, is a cosmopolitan metropolis offering a wide variety of experiences, cuisines and cultural attractions.

While travel to the country may not be possible for most due to the pandemic, the Image of Chile Foundation, a private nonprofit which works closely with the Chilean government to promote tourism in the country, has released an app called Chile 360 which provides users with the opportunity to explore Chile’s vast natural and cultural heritage. Travelers stuck at home can visit the turquoise waters of Patagonia’s Torres del Paine, explore the Rano Kau volcano on Easter Island, and get up close with the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, a famous national landmark in the nation’s capital. The app is free and currently available on the Apple and Google app stores.

5. Visit Kyoto’s Historic Geisha District with Ken’s Tours Kyoto

Cherry blossoms in the Gion neighborhood of Kyoto, Japan. Trevor Dobson. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.