The Republic of the Congo’s world-famous fashionistas strut through the streets of Brazzaville wearing outfits from Europe’s most revered designers. But to sapeurs, their fashion savvy is not just style but a lifestyle.

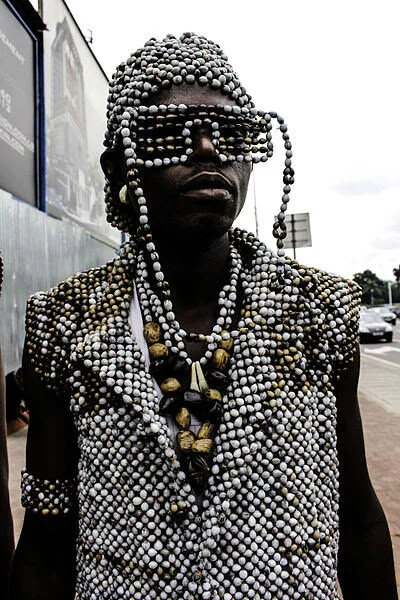

A sapeur in his Sunday best. ilja smets. CC BY-ND 2.0.

Maxime Pivot makes all the ladies scream. Men call him the pride of the town. Children follow him wherever he goes. The Republic of the Congo has never seen a more dashing, debonair, sharp-dressing gentleman. As a modern-day dandy in the streets of Brazzaville, he is a painterly splash of Congo couture amid near-universal penury. He boasts a double-breasted red suit, a pearl-white shirt, pitch-black sunglasses and a pink bowtie, an outfit to amaze the prim and plebeian alike. Rather than envy, his panache inspires pride. Some may call his focus on fashion amid staggering poverty vain, but really, he is preserving a decades-long tradition. He is a sapeur.

That means that he is a member of the Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes—La Sape for short. In English, it translates to the Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People. Every weekend, he and his fellow dandies meet to compare outfits from the hottest European designers, trade notes on color combinations and revel in the pomp of haute couture. They smoke, they dance and they conversate. They escape the squalor in which so many Congolese live—when sapeurs dress up, they feel like the richest men in the world.

No, they are not rich. Quite the opposite. By day, sapeurs are chefs, mechanics, electricians, craftsmen, businessmen, handymen, journeymen, or any other kind of blue-collar worker. 70 percent of people in the Republic of the Congo live in poverty, and most sapeurs are included in that number. What distinguishes them is not wealth but aesthetic distinction, good taste, and a deep knowledge of the latest fashion trends. They aspire to look like a million bucks, not spend it.

The street is a catwalk. Jean-Luc Dalembert. CC BY-SA 4.0.

The tradition began during the Congo’s colonial period. Congolese servants, tired of wearing their Belgian and French colonizers’ secondhand clothes, began saving their wages and purchasing the latest clothes for European dandies. After serving in the French army during World War II, Congolese soldiers returned home bringing closets-worth of European suits, shirts, ties, shoes and accessories. By the time the central African nation gained independence in 1960, many Congolese elites were making pilgrimages to Paris to rack up designer clothes for their wardrobes back home. Although they were accused of relying on white, “Western” traditions, most sapeurs insist on their artistic independence. As Papa Wemba, one of La Sape’s earliest celebrities, said, “White people invented the clothes, but we make an art of it.”

However, investing in clothes instead of, say, property or livestock can be difficult to justify in one of the poorest parts of the world. Many sapeurs hide their expensive lifestyles from relatives to avoid endangering family ties. If a cousin learns that their family member would rather buy an Armani suit or Weston shoes than help put food on the table, they may feel betrayed and break off relations. Furthermore, the wives of sapeurs tend to bear the brunt of the sapeur lifestyle far more heavily than their husbands, as they suffer the financial cost without being able to revel in high fashion.

European style, African art. Opencooper. CC BY-SA 4.0.

La Sape is overwhelmingly male. Overwhelmingly, but not entirely. As the tradition evolves, more women are staking their claim as sapeuses. They, too, don designer suits from Versace, Dior and Yves Saint Laurent and develop mannerisms and gaits to build a persona around their clothes. Even children are beginning to partake in the sapeur culture. Many worry that Congolese tailors lack apprentices to carry on the tradition, so the sight of a child strutting down the streets of Brazzaville in an Armani suit assures them that the legacy of La Sape will continue.

In fact, Maxime Pivot established an organization, Sapeurs in Danger, to preserve the tradition of La Sape, which he asserts is not just about fashion but also is a way of life. When committing to the lifestyle, sapeurs adopt a code of conduct which Ben Mouchaka, another famous sapeur, summed up in 2000. He calls it the Ten Commandments of Sapeology.

1- Thou shalt practise La Sape on Earth with humans and in heaven with God thy creator.

2- Thou shalt bring to heel ngayas (non-connoisseurs), nbéndés (the ignorant), and tindongos (badmouthers) on land, under the earth, at sea and in the skies.

3- Thou shalt honour Sapeology wherever thou goest.

4- The ways of Sapeology are impenetrable for any Sapeologist who does not know the rule of 3: a trilogy of finished and unfinished colours.

5- Thou shalt not give in.

6- Thou shalt demonstrate stringent standards of hygiene in thy body and clothes.

7- Thou shalt not be tribalistic, nationalist, racist or discriminatory.

8- Thou shalt not be violent or insolent.

9- Thou shalt abide by the Sapelogists’ rules of civility and respect thy elders.

10- Through prayer and these 10 commandments, thou, as a Sapeologist, shall conquer the Sapeophobes.

Maxime Pivot aims to pass down the tradition of La Sape to any man, woman, or child willing to devote themselves to the lifestyle. He operates a school of La Sape where he teaches aspiring sapeurs how to combine colors tastefully and craft a swaggering gait. His classes teach that La Sape needn’t sap their wallets. As the sapeur life and style spread, he hopes that dandies will don local brands, not just expensive European ones.

Innovating a classic style. Makangarajustin. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Then, La Sape could be truly independent from European designers. Fashion trends have been increasingly moving in that direction, thanks to Maxime Pivot’s efforts, especially now that La Sape has moved into the mainstream. Every August 15, the Republic of the Congo’s independence day, sapeurs march alongside the military, indigenous tribes and even the President in the largest parade of the year. Their flashy clothes and sauntering stride draw cheers from the crowd. Their tradition provides an example of how the country can emerge from an oppressive European past and spring into a liberated African future.

Michael McCarthy

Michael is an undergraduate student at Haverford College, dodging the pandemic by taking a gap year. He writes in a variety of genres, and his time in high school debate renders political writing an inevitable fascination. Writing at Catalyst and the Bi-Co News, a student-run newspaper, provides an outlet for this passion. In the future, he intends to keep writing in mediums both informative and creative.