In their fight over marginalized peoples and access to rare minerals, the Congolese military and Rwanda-backed rebels risk triggering a broader regional war in southeast Africa.

Read MoreChild Slavery in Congo’s Cobalt Mines

The world’s high demand for cobalt mining has led to the exploitation of child labor in the Congo.

Read MoreWhy You Should Care About the War in Eastern Congo

A decades-old conflict in Central Africa threatens to reignite in full, with worldwide implications.

Read MoreGeneration Z Quits Vaping for the Congo

Rampant child labor in the Congo has ignited an ethical social movement among Generation Z.

Child Mining in Kailo, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Julien Harneis. CC BY 2.0

Many young people have recently decided to quit vaping, not because of health risks like their parents with smoking but to instead protest child labor in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Since gaining its independence in 1960, the DRC has experienced persistent hostilities in its Eastern provinces. In the last six weeks alone, violence in the North Kivu province has displaced more than 450,000 people. The intensification of violence has additionally resulted in devastating impacts on the lives of children, who have been forced into child labor.

Based on statistics from the Bureau of International Labor Affairs in 2022, 17.4% of children aged 5 to 14 in the DRC are working full-time. This includes over 40,000 child laborers toiling in cobalt mines in one province alone, according to UN agencies. The work that the children do is divided into multiple activities, including but not limited to agriculture, industry and services. The categorical worst form of child labor is forced mining. As a country that holds more than 50% of the world’s cobalt reserves, the DRC is a global leader in its production in artisanal mines. However, as a result of the nation’s poverty rates, child labor is common in this sector and deemed a necessity. Impoverished parents who can not afford to send their children to school have them contribute to the household by working. Even with the DRC Child Protection Code of 2009 that provides “free and compulsory primary education,” there is not enough government support and funding to take this financial responsibility off of parents. In 2022, the DRC made minimal advancements in efforts to eliminate child labor in its worst forms, causing Gen Z to take matters into its own hands.

Gen Z, characteristically hooked on vaping, has decided to quit the habit to stand in solidarity with those working in the DRC. The movement initially began on TikTok and has since spread, condemning vapes not for the cost or risks, but for their materials. Vapes have lithium-ion batteries that are made of raw minerals, including cobalt. As demand for vapes and other lithium containing products grows, there will be a greater need for lithium production, exacerbating existing problems for the mining industry and its workers. Already, the conditions for workers in the mines are harsh. Of the 255,000 Congolese citizens mining cobalt, 40,000 are children in the country’s southeast who dig all day in mines with small shovels or their bare hands for searing-hot stones. Children excavate materials in ditches or rivers where they have to haul the metal that they find. This work in a mine can last up to 12 hours each day to earn only between one and two dollars. For an industry that was estimated at USD 15.97 billion in 2022 and is anticipated to grow 6.2% from 2023 to 2030, child laborers are earning significantly less than those industries that they produce cobalt for. Glencore, the largest cobalt-producing company, achieved a total production of 25,320 metric tons in 2021 and is estimated to be worth nearly $68 billion. In 2022, Glencore’s annual revenue amounted to just under $256 billion, the highest of any mining company in the world.

Gen Z has seemed unmoved by the health risks associated with vaping, but have taken up the call for social justice very seriously. A number of users have taken to TikTok to call attention to the humanitarian crisis in the Congo and how the West’s demand for cobalt has resulted in a massive increase in child labor. Whether it has been Gen Zers announcing their own decision to quit vaping or spreading information about the emergency in the hopes of influencing others, the movement has certainly gained traction. Amid concerns about the environment and material waste in landfills, users have reshaped the conversation to show how scrapped product only perpetuates demand. An estimated 150 million vapes are being disposed of in the United States each year, with two-thirds of 15–24 year old users placing them straight into the trash, despite the devices’ reusable batteries. This has contributed to the billions of dollars in funding for unnecessary mining, causing those online to call for collective action to stop and consider the ethical implications of their purchase. Much of the conversation has shifted into the interconnectedness of consumerism and its impact on vulnerable workers.

The government of the DRC has established policies related to child labor, but a lack of regional scope has hindered their effects. The National Sectoral Strategy to Combat Child Labor in Artisanal Mines and Artisanal Mining Sites was developed to eradicate child labor in mines by 2025. Its strategy aims to strengthen laws, promote responsible sourcing and improve child protection measures. Additionally, the Child Labor Monitoring System was launched to identify and remove children from mines. These efforts seek to raise awareness of child labor at its worst form and empower communities to stop these practices. However, the government of the DRC does not currently have policies to address the issue of child labor at a regional level, making it unlikely that the mining sector will be much changed. However, because the internet has emerged as a powerful tool for social change, Gen Z hopes to take advantage of it to boycott human rights abuses. By leveraging social media to create changes in their own behavior, the youth aim to limit the ability of companies to compromise human rights for a profit.

Mira White

Mira is a student at Brown University studying international and public affairs. Passionate about travel and language learning, she is eager to visit each continent to better understand the world and the people across it. In her free time she perfects her French, hoping to someday live in France working as a freelance journalist or in international affairs.

Report Finds W.H.O. Workers Sexually Exploited Women During Ebola Mission

Women were sexually exploited and abused by aid workers in order to obtain or keep jobs during the Ebola Crisis in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

A young girl washes her hands at a checkpoint at the border between Uganda and the DRC. UK Department for International Development. CC BY 2.0

According to a report commissioned by the agency’s head, World Health Organization workers sexually abused women while in the Democratic Republic of the Congo to aid the Ebola outbreak from 2018 to 2020. The report found that 83 people participated in the abuse, and in 21 cases, those involved were confirmed to be WHO officials. The investigation started in September 2020 when The New Humanitarian and the Thomas Reuters Foundation published a report investigating abuse claims. The report found that 31 out of 50 women interviewed reported abuse and exploitation from men working for the WHO. In response, leadership in the World Health Organization ordered an independent commission to investigate. After working in Beni, one woman interviewed by the commission stated, “To get ahead in the job, you had to have sex … Everyone had sex in exchange for something. It was very common.” In addition, women reported that they were sexually harrassed and faced exploitation in order to keep their jobs, get paid or get a promotion. In some cases women were dismissed from their jobs when they refused to have sex with supervisors.

The commission established that the majority of the victims were already vulnerable because of precarious social and economic status, and women with more education and economic power were less vulnerable to abuse. The report found that there was a “systematic tendency to reject all reports of sexual exploitation and abuse unless they were made in writing”. While the WHO has training in place to prevent sexual abuse, the report found that training for employees did not happen until November 2019, months after the outbreak had been declared an emergency. Only 371 out of 2,800 workers attended the training. Additionally, men make up the vast majority of employees during the crisis, averaging 73.4% overall. The report cites that men held 77.49% of leadership positions and 91.52% of operations support and logistic positions.

The WHO was not the only organization accused of abuse, The New Humanitarian’s investigation found that there were allegations against workers at World Vision, Unicef and Alima, among others. Additionally, the investigation found that underreporting was prevalent in these cases, with one woman stating, “Why would you even ask if I reported it?” The New Humanitarian found that many women were unaware of how to report abuse or exploitation at all. Most aid agencies claimed they had received no reports of abuse, and the WHO stated they had received only a small number of complaints. Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the Director-General of the WHO, apologized to victims and said it was his top priority to hold perpetrators accountable during a press conference after the report’s publication.

Dana Flynn

Dana is a recent graduate from Tufts University with a degree in English. While at Tufts she enjoyed working on a campus literary magazine and reading as much as possible. Originally from the Pacific Northwest, she loves to explore and learn new things.

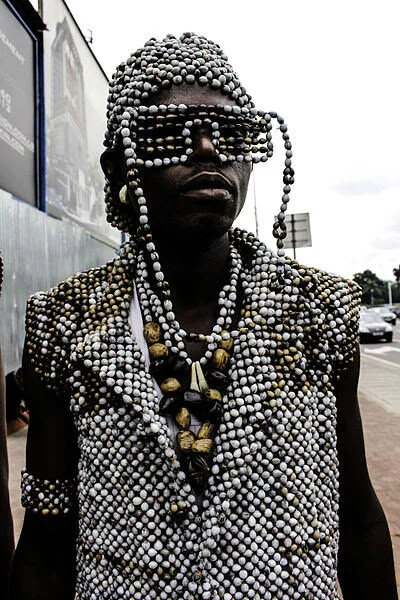

Congo Couture: “Sapeurs” Bring Europe’s Designer Fashion to Central Africa

The Republic of the Congo’s world-famous fashionistas strut through the streets of Brazzaville wearing outfits from Europe’s most revered designers. But to sapeurs, their fashion savvy is not just style but a lifestyle.

A sapeur in his Sunday best. ilja smets. CC BY-ND 2.0.

Maxime Pivot makes all the ladies scream. Men call him the pride of the town. Children follow him wherever he goes. The Republic of the Congo has never seen a more dashing, debonair, sharp-dressing gentleman. As a modern-day dandy in the streets of Brazzaville, he is a painterly splash of Congo couture amid near-universal penury. He boasts a double-breasted red suit, a pearl-white shirt, pitch-black sunglasses and a pink bowtie, an outfit to amaze the prim and plebeian alike. Rather than envy, his panache inspires pride. Some may call his focus on fashion amid staggering poverty vain, but really, he is preserving a decades-long tradition. He is a sapeur.

That means that he is a member of the Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes—La Sape for short. In English, it translates to the Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People. Every weekend, he and his fellow dandies meet to compare outfits from the hottest European designers, trade notes on color combinations and revel in the pomp of haute couture. They smoke, they dance and they conversate. They escape the squalor in which so many Congolese live—when sapeurs dress up, they feel like the richest men in the world.

No, they are not rich. Quite the opposite. By day, sapeurs are chefs, mechanics, electricians, craftsmen, businessmen, handymen, journeymen, or any other kind of blue-collar worker. 70 percent of people in the Republic of the Congo live in poverty, and most sapeurs are included in that number. What distinguishes them is not wealth but aesthetic distinction, good taste, and a deep knowledge of the latest fashion trends. They aspire to look like a million bucks, not spend it.

The street is a catwalk. Jean-Luc Dalembert. CC BY-SA 4.0.

The tradition began during the Congo’s colonial period. Congolese servants, tired of wearing their Belgian and French colonizers’ secondhand clothes, began saving their wages and purchasing the latest clothes for European dandies. After serving in the French army during World War II, Congolese soldiers returned home bringing closets-worth of European suits, shirts, ties, shoes and accessories. By the time the central African nation gained independence in 1960, many Congolese elites were making pilgrimages to Paris to rack up designer clothes for their wardrobes back home. Although they were accused of relying on white, “Western” traditions, most sapeurs insist on their artistic independence. As Papa Wemba, one of La Sape’s earliest celebrities, said, “White people invented the clothes, but we make an art of it.”

However, investing in clothes instead of, say, property or livestock can be difficult to justify in one of the poorest parts of the world. Many sapeurs hide their expensive lifestyles from relatives to avoid endangering family ties. If a cousin learns that their family member would rather buy an Armani suit or Weston shoes than help put food on the table, they may feel betrayed and break off relations. Furthermore, the wives of sapeurs tend to bear the brunt of the sapeur lifestyle far more heavily than their husbands, as they suffer the financial cost without being able to revel in high fashion.

European style, African art. Opencooper. CC BY-SA 4.0.

La Sape is overwhelmingly male. Overwhelmingly, but not entirely. As the tradition evolves, more women are staking their claim as sapeuses. They, too, don designer suits from Versace, Dior and Yves Saint Laurent and develop mannerisms and gaits to build a persona around their clothes. Even children are beginning to partake in the sapeur culture. Many worry that Congolese tailors lack apprentices to carry on the tradition, so the sight of a child strutting down the streets of Brazzaville in an Armani suit assures them that the legacy of La Sape will continue.

In fact, Maxime Pivot established an organization, Sapeurs in Danger, to preserve the tradition of La Sape, which he asserts is not just about fashion but also is a way of life. When committing to the lifestyle, sapeurs adopt a code of conduct which Ben Mouchaka, another famous sapeur, summed up in 2000. He calls it the Ten Commandments of Sapeology.

1- Thou shalt practise La Sape on Earth with humans and in heaven with God thy creator.

2- Thou shalt bring to heel ngayas (non-connoisseurs), nbéndés (the ignorant), and tindongos (badmouthers) on land, under the earth, at sea and in the skies.

3- Thou shalt honour Sapeology wherever thou goest.

4- The ways of Sapeology are impenetrable for any Sapeologist who does not know the rule of 3: a trilogy of finished and unfinished colours.

5- Thou shalt not give in.

6- Thou shalt demonstrate stringent standards of hygiene in thy body and clothes.

7- Thou shalt not be tribalistic, nationalist, racist or discriminatory.

8- Thou shalt not be violent or insolent.

9- Thou shalt abide by the Sapelogists’ rules of civility and respect thy elders.

10- Through prayer and these 10 commandments, thou, as a Sapeologist, shall conquer the Sapeophobes.

Maxime Pivot aims to pass down the tradition of La Sape to any man, woman, or child willing to devote themselves to the lifestyle. He operates a school of La Sape where he teaches aspiring sapeurs how to combine colors tastefully and craft a swaggering gait. His classes teach that La Sape needn’t sap their wallets. As the sapeur life and style spread, he hopes that dandies will don local brands, not just expensive European ones.

Innovating a classic style. Makangarajustin. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Then, La Sape could be truly independent from European designers. Fashion trends have been increasingly moving in that direction, thanks to Maxime Pivot’s efforts, especially now that La Sape has moved into the mainstream. Every August 15, the Republic of the Congo’s independence day, sapeurs march alongside the military, indigenous tribes and even the President in the largest parade of the year. Their flashy clothes and sauntering stride draw cheers from the crowd. Their tradition provides an example of how the country can emerge from an oppressive European past and spring into a liberated African future.

Michael McCarthy

Michael is an undergraduate student at Haverford College, dodging the pandemic by taking a gap year. He writes in a variety of genres, and his time in high school debate renders political writing an inevitable fascination. Writing at Catalyst and the Bi-Co News, a student-run newspaper, provides an outlet for this passion. In the future, he intends to keep writing in mediums both informative and creative.

Conflict Zones Through The Lens of Marcus Bleasdale

“This is an exciting time for digital storytellers.”

Truer words have never been spoken. But in the spirit of the commencement of this year’s Social Good Summit, it should be noted that these storytellers also hold a great responsibility to the masses. As a distinguished photographer, Marcus Bleasdale embodies this sense of responsibility in his coverage of conflict areas around the world through the medium of his trusted camera lens. Over the past 15 years, the region of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has captured his steady attention.

Throughout his time working within the DRC, Bleasdale has gained a first-hand perspective into a nation that, while rich in minerals, has been coerced into a haunting reality of violence, disease, poverty and profound injustice. Children are stripped of their adolescence, forced into militant lives plagued by mindless violence at the behest of their devious superiors. Families are torn apart, displaced, and involuntary bare witness to the perils of life within the misleading comfort of their own backyards.

More

As the conflict within the borders has continued to run its rampant course over the past 15+ years, 2 million Congolese natives have been displaced, 40,000 women fall victim of sexual violence annually, and over 5.5 million deaths have been recorded as a result of rampant disease, and violence throughout the region. In his Keynote adderess to the Social Good audience, Bleasdale stressed that these are simply the statistics; his images however, are what interpret the reality.

An important distinction however, is how Bleasdale goes about creating a narrative of an area so riddled by conflict for decades. He goes into depth about how he works to construct such a narrative in saying:

“For me, I’m trying to engage in order to enhance the narrative that I’m trying to tell. There are many different aspects of the story to engage with - the mind, the child soldiers, the sexual violence, displacement, horrific health issues that have spread through the DRC. I have to touch on each one of those in each unique situation to try and engage with a subject in a way that will truly hone the message that this should stop.”

He delves deeper in his philosophy toward photojournalism in conflict areas, stating, “Every image cannot be misery, and should not be so difficult to look at that you want to turn away. You have to also try to look for the beauty, and the hope, to show the opportunity that is available that has not necessarily been seized.”

Having covered the Democratic Republic of Congo for more than 15 years now, Bleasdale’s knowledge and wisdom towards his craft should be respected. As for his advice for the brave soul aspiring to photojournalism of this nature; one word came to mind, patience.

“Everything takes time, especially when working within the areas I have. In relation to my work in the DRC, you can’t tell that story in a week, a month. I’ve been telling that story for 15 years now and still I don’t think it’s finished, because it’s still going on.“

An award-winning photographer who has been heralded by the US House of Representatives, The United Nations and the House of Parliament in the UK, Bleasedale will undoubtedly continue to be a respected voice within the realm of photography, specifically within regions of conflict.

He can be followed on twitter @marcusbleasedale.

ANDREW BRIDGE @Bridgin_TheGap

Andrew is Editor-in-Chief of CATALYST's Social Good Summit Daily, and Managing Editor of CATALYST. He is a global enthusiast with a passion for the road less traveled. As a frequent collaborator with World Hip Hop Market and Nomadic Wax, Andrew has worked with numerous socially conscious artists from around the world in the pursuit of inspiring cultural understanding and exchange through entertainment. This fascination with the world at large has taken him to over 20 countries (so far) through studying, volunteering, and writing about his travels, with no signs of slowing.