A decades-old conflict in Central Africa threatens to reignite in full, with worldwide implications.

Read MoreHow King Leopold’s Colonial Legacy Still Haunts the Congo Today

Occupied by Belgians for almost 80 years, the effects of colonization still resonate in the Democratic Republic of the Congo decades after independence.

A refugee center in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. United Nations Photo. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

As the leader of the small European country of Belgium in the 1880s, King Leopold II did not have much political clout with his fellow European statesmen. He wanted more political power so he achieved this by gaining personal control of a vast swath of Central Africa, which became the Congo Free State. King Leopold ruthlessly subjugated the local populations of the region in order to extract as much raw materials such as ivory and rubber as possible, committing human rights violations in the process. It was not until 1902 when Joseph Conrad published the novel Heart of Darkness criticizing Leopold’s administration of the Congo and in 1904 when Edmund Dene Morel published a report detailing the atrocities in the Congo did Western public opinion turn against King Leopold, who was forced in 1908 to relinquish control of the Congo Free State to the Belgian government.

Today, those atrocities committed by King Leopold and the Belgians are still felt by the area, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The relationship that the Belgian colonial administration espoused was one of paternalism, where the Congolese were treated like children, which resulted in them unprepared for self-determination. When the DRC gained independence in 1960, it plunged into a state of sporadic political conflicts due to the dictatorship of Mobutu Sese Seko that lasted until the 1990s. The peace that ended that drawn out conflict only lasted a short time, and violence soon erupted again.

Currently, the eastern region of the country is held by at least 122 rebel groups, with the legitimate government struggling to control the region. That has caused more than 5 million people to be displaced between 2017 and 2019 and an additional 72,000 and counting since May 2022, with many fleeing areas controlled by rebel groups. Many areas receiving refugees are overwhelmed and do not have the proper infrastructure to support them.

The almost incessant warfare since independence may seem unconnected to the legacy of imperialism, but that is not the case. The seeds for the present political instability were sowed when the Congo was under Belgian rule. The Congo is a region with vast natural resources, from ivory and rubber of old to the mineral wealth of today. The abundance of raw materials and resources was exactly why Congo was colonized. When the borders of Africa were carved up by European powers, no regard was made to the various tribes already living in the area. Some groups of people were divided between different countries, and enemy tribes sometimes found themselves within the same domain. When the DRC gained independence, the various tribes were not united, leading to no coherent vision for the future of the country, thus sowing political instability.

In addition, since the purpose of the Congo Free State was solely to enrich King Leopold and later Belgium, there was no effort to develop a political or academic class among the local population. As such, at independence, there was no model of self-governance to follow after decades of infantilization by Europeans. That caused Mobutu Sese Seko to take advantage of the power vacuum and install himself dictator for more than 30 years.

The international response to the violence in the DRC has deprived the country of even more of its sustenance. International companies are refusing to do business with the DRC due to its human rights violations, depriving many of the mining jobs that they depend on. In order to survive, those people end up joining rebel groups, further perpetuating the violence.

The cycle of violence that started with Belgian occupation did not end in the 1990s. Subsequent leaders of the DRC used violence to consolidate their rule, since that was the only method they ever experienced. But, efforts have been made to ensure a sustainable future. The UN is stepping in by giving the DRC a peacebuilding fund to provide services to ex-rebels to reintegrate into their communities and to support over 300 women miners to better manage their sites and defend their rights. UNICEF also supports school reopenings, an essential indicator of peace. By prioritizing the reopening of schools in conflict zones, UNICEF ensures peaceful coexistence after prolonged conflict. The outside aid that the DRC is receiving gives local communities the agency to control their future.

To Get Involved

Cordaid is one organization providing humanitarian aid to the region. Another organization working to improve conditions by enabling local communities to form cooperatives that can successfully sustain peace in the communities in the DRC is Peace Direct.

Bryan Fok

Bryan is currently a History and Global Affairs major at the University of Notre Dame. He aims to apply the notion of Integral Human Development as a framework for analyzing global issues. He enjoys hiking and visiting national parks.

Report Finds W.H.O. Workers Sexually Exploited Women During Ebola Mission

Women were sexually exploited and abused by aid workers in order to obtain or keep jobs during the Ebola Crisis in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

A young girl washes her hands at a checkpoint at the border between Uganda and the DRC. UK Department for International Development. CC BY 2.0

According to a report commissioned by the agency’s head, World Health Organization workers sexually abused women while in the Democratic Republic of the Congo to aid the Ebola outbreak from 2018 to 2020. The report found that 83 people participated in the abuse, and in 21 cases, those involved were confirmed to be WHO officials. The investigation started in September 2020 when The New Humanitarian and the Thomas Reuters Foundation published a report investigating abuse claims. The report found that 31 out of 50 women interviewed reported abuse and exploitation from men working for the WHO. In response, leadership in the World Health Organization ordered an independent commission to investigate. After working in Beni, one woman interviewed by the commission stated, “To get ahead in the job, you had to have sex … Everyone had sex in exchange for something. It was very common.” In addition, women reported that they were sexually harrassed and faced exploitation in order to keep their jobs, get paid or get a promotion. In some cases women were dismissed from their jobs when they refused to have sex with supervisors.

The commission established that the majority of the victims were already vulnerable because of precarious social and economic status, and women with more education and economic power were less vulnerable to abuse. The report found that there was a “systematic tendency to reject all reports of sexual exploitation and abuse unless they were made in writing”. While the WHO has training in place to prevent sexual abuse, the report found that training for employees did not happen until November 2019, months after the outbreak had been declared an emergency. Only 371 out of 2,800 workers attended the training. Additionally, men make up the vast majority of employees during the crisis, averaging 73.4% overall. The report cites that men held 77.49% of leadership positions and 91.52% of operations support and logistic positions.

The WHO was not the only organization accused of abuse, The New Humanitarian’s investigation found that there were allegations against workers at World Vision, Unicef and Alima, among others. Additionally, the investigation found that underreporting was prevalent in these cases, with one woman stating, “Why would you even ask if I reported it?” The New Humanitarian found that many women were unaware of how to report abuse or exploitation at all. Most aid agencies claimed they had received no reports of abuse, and the WHO stated they had received only a small number of complaints. Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the Director-General of the WHO, apologized to victims and said it was his top priority to hold perpetrators accountable during a press conference after the report’s publication.

Dana Flynn

Dana is a recent graduate from Tufts University with a degree in English. While at Tufts she enjoyed working on a campus literary magazine and reading as much as possible. Originally from the Pacific Northwest, she loves to explore and learn new things.

Congo Couture: “Sapeurs” Bring Europe’s Designer Fashion to Central Africa

The Republic of the Congo’s world-famous fashionistas strut through the streets of Brazzaville wearing outfits from Europe’s most revered designers. But to sapeurs, their fashion savvy is not just style but a lifestyle.

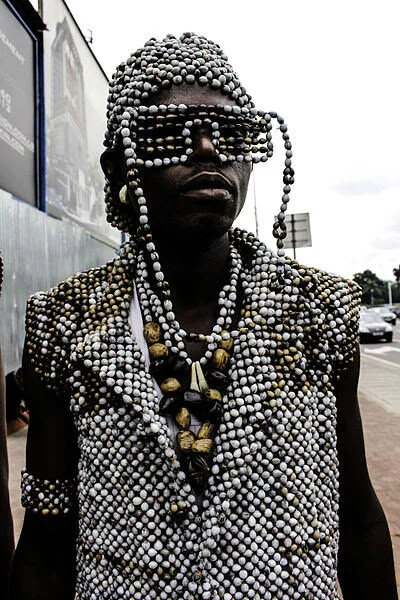

A sapeur in his Sunday best. ilja smets. CC BY-ND 2.0.

Maxime Pivot makes all the ladies scream. Men call him the pride of the town. Children follow him wherever he goes. The Republic of the Congo has never seen a more dashing, debonair, sharp-dressing gentleman. As a modern-day dandy in the streets of Brazzaville, he is a painterly splash of Congo couture amid near-universal penury. He boasts a double-breasted red suit, a pearl-white shirt, pitch-black sunglasses and a pink bowtie, an outfit to amaze the prim and plebeian alike. Rather than envy, his panache inspires pride. Some may call his focus on fashion amid staggering poverty vain, but really, he is preserving a decades-long tradition. He is a sapeur.

That means that he is a member of the Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes—La Sape for short. In English, it translates to the Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People. Every weekend, he and his fellow dandies meet to compare outfits from the hottest European designers, trade notes on color combinations and revel in the pomp of haute couture. They smoke, they dance and they conversate. They escape the squalor in which so many Congolese live—when sapeurs dress up, they feel like the richest men in the world.

No, they are not rich. Quite the opposite. By day, sapeurs are chefs, mechanics, electricians, craftsmen, businessmen, handymen, journeymen, or any other kind of blue-collar worker. 70 percent of people in the Republic of the Congo live in poverty, and most sapeurs are included in that number. What distinguishes them is not wealth but aesthetic distinction, good taste, and a deep knowledge of the latest fashion trends. They aspire to look like a million bucks, not spend it.

The street is a catwalk. Jean-Luc Dalembert. CC BY-SA 4.0.

The tradition began during the Congo’s colonial period. Congolese servants, tired of wearing their Belgian and French colonizers’ secondhand clothes, began saving their wages and purchasing the latest clothes for European dandies. After serving in the French army during World War II, Congolese soldiers returned home bringing closets-worth of European suits, shirts, ties, shoes and accessories. By the time the central African nation gained independence in 1960, many Congolese elites were making pilgrimages to Paris to rack up designer clothes for their wardrobes back home. Although they were accused of relying on white, “Western” traditions, most sapeurs insist on their artistic independence. As Papa Wemba, one of La Sape’s earliest celebrities, said, “White people invented the clothes, but we make an art of it.”

However, investing in clothes instead of, say, property or livestock can be difficult to justify in one of the poorest parts of the world. Many sapeurs hide their expensive lifestyles from relatives to avoid endangering family ties. If a cousin learns that their family member would rather buy an Armani suit or Weston shoes than help put food on the table, they may feel betrayed and break off relations. Furthermore, the wives of sapeurs tend to bear the brunt of the sapeur lifestyle far more heavily than their husbands, as they suffer the financial cost without being able to revel in high fashion.

European style, African art. Opencooper. CC BY-SA 4.0.

La Sape is overwhelmingly male. Overwhelmingly, but not entirely. As the tradition evolves, more women are staking their claim as sapeuses. They, too, don designer suits from Versace, Dior and Yves Saint Laurent and develop mannerisms and gaits to build a persona around their clothes. Even children are beginning to partake in the sapeur culture. Many worry that Congolese tailors lack apprentices to carry on the tradition, so the sight of a child strutting down the streets of Brazzaville in an Armani suit assures them that the legacy of La Sape will continue.

In fact, Maxime Pivot established an organization, Sapeurs in Danger, to preserve the tradition of La Sape, which he asserts is not just about fashion but also is a way of life. When committing to the lifestyle, sapeurs adopt a code of conduct which Ben Mouchaka, another famous sapeur, summed up in 2000. He calls it the Ten Commandments of Sapeology.

1- Thou shalt practise La Sape on Earth with humans and in heaven with God thy creator.

2- Thou shalt bring to heel ngayas (non-connoisseurs), nbéndés (the ignorant), and tindongos (badmouthers) on land, under the earth, at sea and in the skies.

3- Thou shalt honour Sapeology wherever thou goest.

4- The ways of Sapeology are impenetrable for any Sapeologist who does not know the rule of 3: a trilogy of finished and unfinished colours.

5- Thou shalt not give in.

6- Thou shalt demonstrate stringent standards of hygiene in thy body and clothes.

7- Thou shalt not be tribalistic, nationalist, racist or discriminatory.

8- Thou shalt not be violent or insolent.

9- Thou shalt abide by the Sapelogists’ rules of civility and respect thy elders.

10- Through prayer and these 10 commandments, thou, as a Sapeologist, shall conquer the Sapeophobes.

Maxime Pivot aims to pass down the tradition of La Sape to any man, woman, or child willing to devote themselves to the lifestyle. He operates a school of La Sape where he teaches aspiring sapeurs how to combine colors tastefully and craft a swaggering gait. His classes teach that La Sape needn’t sap their wallets. As the sapeur life and style spread, he hopes that dandies will don local brands, not just expensive European ones.

Innovating a classic style. Makangarajustin. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Then, La Sape could be truly independent from European designers. Fashion trends have been increasingly moving in that direction, thanks to Maxime Pivot’s efforts, especially now that La Sape has moved into the mainstream. Every August 15, the Republic of the Congo’s independence day, sapeurs march alongside the military, indigenous tribes and even the President in the largest parade of the year. Their flashy clothes and sauntering stride draw cheers from the crowd. Their tradition provides an example of how the country can emerge from an oppressive European past and spring into a liberated African future.

Michael McCarthy

Michael is an undergraduate student at Haverford College, dodging the pandemic by taking a gap year. He writes in a variety of genres, and his time in high school debate renders political writing an inevitable fascination. Writing at Catalyst and the Bi-Co News, a student-run newspaper, provides an outlet for this passion. In the future, he intends to keep writing in mediums both informative and creative.

A health worker walking outside of the ALIMA Ebola Treatment Center in the Democratic Republic of Congo in January 2019. World Bank Photo Collection. CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Congo Faces New Ebola Outbreak Amid Global Pandemic

The World Health Organization has called on the international community for financial support and aid in combating the latest Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo. This latest outbreak was announced by the country’s government on June 1 and has seen 56 cases reported in the Equateur province, a region which has been a hot spot for the disease in recent years.

Ebola is a deadly disease with outbreaks occurring primarily in Africa. In humans, the virus can be caused by one of four virus species: Ebola virus, Sudan virus, Tai Forest virus and Bundibugyo virus. The virus spreads through direct contact with organic matter from infected humans and animals. Common symptoms include fever, aches, weakness, fatigue, abdominal pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, and hemorrhaging, bleeding and bruising.

This latest outbreak comes as the 11th in a long line of Ebola outbreaks in the Congo since the disease was first discovered in 1976. A couple of weeks ago, the WHO celebrated the end of the country’s 10th outbreak, which began in August 2018. That Ebola outbreak was the deadliest recorded in the DRC and second worst in history, seeing 2,280 deaths.

According to The New York Times, the WHO has gathered $1.75 million to combat the outbreak, but this funding would only last the organization for a couple more weeks. Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, the WHO’s regional director for Africa, called for additional funding to be allocated toward vaccinations, testing and treatment, as well as contact tracing and health education resources.

“Responding to Ebola in the midst of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is complex, but we must not let COVID-19 distract us from tackling other pressing health threats,” Dr. Moeti said. “The current Ebola outbreak is running into headwinds because cases are scattered across remote areas in dense rainforests. This makes for a costly response as ensuring that responders and supplies reach affected populations is extremely challenging.”

Dr. Moeti also stated that over 12,000 people living in the Equateur province had been vaccinated since the outbreak was first reported in June.

WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus echoed Dr. Moeti’s sentiments in a recent news release on the situation.

“This is a reminder that COVID-19 is not the only health threat people face,” Dr. Ghebreyesus said. “Although much of our attention is on the pandemic, WHO is continuing to monitor and respond to many other health emergencies.”

This call for funding follows a challenging six months for the organization, as the WHO has partnered with global leaders to combat the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

While much of the world has been supportive of the organization, the United States has been an exception. President Donald Trump pulled the country out of the WHO in late May over concerns about Chinese influence, with the withdrawal going into effect on July 6, 2021. The U.S. is the organization’s single largest financial contributor, having provided over $400 million in 2019.

President Trump has not publicly commented on this latest Ebola outbreak. While the U.S. directed $21 million in aid through the U.S. Agency for International Development for the 10th outbreak in 2019, it is unclear whether the country will direct any funding toward this latest outbreak’s relief efforts.

The WHO is expected to continue Ebola relief operations within the Equateur province for the foreseeable future, as governmental agencies such as the United Nations have directed additional funding to the organization. However, it is unclear how long this funding will last and how the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic will complicate these relief measures.

Jacob Sutherland

is a recent graduate from the University of California San Diego where he majored in Political Science and minored in Spanish Language Studies. He previously served as the News Editor for The UCSD Guardian, and hopes to shed light on social justice issues in his work.

Congolese overlook the site of a copper mine in the country’s Haut-Katanga province. Fairphone. CC BY-NC 2.0

Coronavirus—the Newest Excuse for Miners’ Mistreatment in the Congo

In the far south of the Democratic Republic of Congo lies the Copperbelt, a region that leads Africa in copper production and accounts for 70% of the world’s cobalt supply. The area’s mines play a key role in supplying the world with electrical wires and the batteries found inside smartphones and electric cars.

The Congo’s Copperbelt is also a region of severe worker mistreatment. Miners, often children, receive around $1 a day as they toil in shafts prone to collapse for long hours. This occurs while cobalt’s market price hovers at nearly $30,000 per ton.

As COVID-19 ravages Africa, copper and cobalt mines in the Congo have adjusted by instituting harsh rules to curb the virus’s impact on their production levels. The mines’ provisions have, unsurprisingly, not been in workers’ favor. The adjustments, confirmed by workers and union representatives, include:

· Mandatory confinement at mine sites, 24 hours per day, or risk losing employment

· Extended shifts without receiving additional pay

· Inadequate food and water rations

· Overcrowded sleeping arrangements and unsanitary toilet and hand-washing facilities

· Limited or nonexistent communication about the confinement’s duration or future COVID-19 measures

The response to allegations of further worker mistreatment in the Congo has been immediate. Eleven human rights groups, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, sent a letter to 13 mining corporations across the region setting standards for worker treatment.

“We believe that companies around the world will be remembered,” the letter states, “by how they treat their workers during these challenging times. At a minimum, companies should not require workers to be held in mandatory confinement under threat of unemployment, should provide adequate personal protective equipment and access to water and sanitation facilities for all workers, and employ social distancing measures at all times.”

Whether the suggested guidelines will be followed in the Copperbelt remains to be seen. Mining titans Glencore, Eurasian Resources Group, Chemaf, Huayou Cobalt and Ivanhoe Mines declined to immediately respond to requests for comment.

Workers shovel copper into railway cars at a processing plant in Lubumbashi, from where it will be sent abroad. International Labour Organization ILO. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Pressure has been mounting on copper and cobalt producers – and their recipients – for years. International Rights Advocates, a human rights lobbying group, filed suit against Apple, Google, Microsoft, Dell and Tesla in December 2019 accusing them of “knowingly benefiting from” the use of child labor at Congolese mines. While the companies restated their commitment to “only sourcing responsibly-produced materials,” very few tangible steps have been taken.

The problem, then, continues today. Though Apple revealed its full list of cobalt suppliers upon request, many major companies cannot verify that their supply chains are free of worker mistreatment. Faced with slim human rights pressure from buyers and a generally impoverished workforce, most cobalt and copper producers feel little incentive to change. Their COVID-19 response so far stands as only the most recent example.

Accountability remains the first step toward ending the mistreatment of Congolese miners. Supply chain traceability alone could prevent companies from buying minerals unearthed by unprotected workers facing mandatory confinement. A positive step came in late May when Huayou Cobalt, China’s top producer, agreed to temporarily stop sourcing cobalt from the informal sector “until relevant standards can be recognized and supported by the whole industry.”

While this step is welcome, much more can be done. COVID-19’s spread complicates mines’ production efforts, but by no means necessitates mandatory confinement, threats to employment, and steep cuts to health and wellness standards. Groups such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and Rights and Accountability in Government are working to fight against worker mistreatment, and this letter is just the first move.

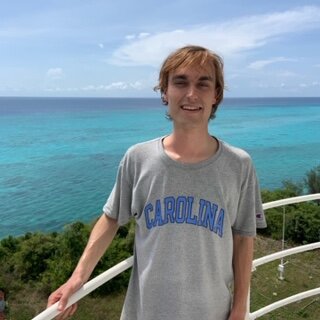

Stephen Kenney

is a Journalism and Political Science double major at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He enjoys sharing his passion for geography with others by writing compelling stories from across the globe. In his free time, Stephen enjoys reading, long-distance running and rooting for the Tar Heels.

I am Congo

Get to know the Congo before you walk through the streets yourself. In this immersive experience, you'll see the vast forest of the congo, the countries colorful style, and break taking shots of life in the city. As part of the "I am" series, videographers spent time in the Congo meeting local artisans, traders and musicians. Their experience, laid out for you here.

Conflict Zones Through The Lens of Marcus Bleasdale

“This is an exciting time for digital storytellers.”

Truer words have never been spoken. But in the spirit of the commencement of this year’s Social Good Summit, it should be noted that these storytellers also hold a great responsibility to the masses. As a distinguished photographer, Marcus Bleasdale embodies this sense of responsibility in his coverage of conflict areas around the world through the medium of his trusted camera lens. Over the past 15 years, the region of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has captured his steady attention.

Throughout his time working within the DRC, Bleasdale has gained a first-hand perspective into a nation that, while rich in minerals, has been coerced into a haunting reality of violence, disease, poverty and profound injustice. Children are stripped of their adolescence, forced into militant lives plagued by mindless violence at the behest of their devious superiors. Families are torn apart, displaced, and involuntary bare witness to the perils of life within the misleading comfort of their own backyards.

More

As the conflict within the borders has continued to run its rampant course over the past 15+ years, 2 million Congolese natives have been displaced, 40,000 women fall victim of sexual violence annually, and over 5.5 million deaths have been recorded as a result of rampant disease, and violence throughout the region. In his Keynote adderess to the Social Good audience, Bleasdale stressed that these are simply the statistics; his images however, are what interpret the reality.

An important distinction however, is how Bleasdale goes about creating a narrative of an area so riddled by conflict for decades. He goes into depth about how he works to construct such a narrative in saying:

“For me, I’m trying to engage in order to enhance the narrative that I’m trying to tell. There are many different aspects of the story to engage with - the mind, the child soldiers, the sexual violence, displacement, horrific health issues that have spread through the DRC. I have to touch on each one of those in each unique situation to try and engage with a subject in a way that will truly hone the message that this should stop.”

He delves deeper in his philosophy toward photojournalism in conflict areas, stating, “Every image cannot be misery, and should not be so difficult to look at that you want to turn away. You have to also try to look for the beauty, and the hope, to show the opportunity that is available that has not necessarily been seized.”

Having covered the Democratic Republic of Congo for more than 15 years now, Bleasdale’s knowledge and wisdom towards his craft should be respected. As for his advice for the brave soul aspiring to photojournalism of this nature; one word came to mind, patience.

“Everything takes time, especially when working within the areas I have. In relation to my work in the DRC, you can’t tell that story in a week, a month. I’ve been telling that story for 15 years now and still I don’t think it’s finished, because it’s still going on.“

An award-winning photographer who has been heralded by the US House of Representatives, The United Nations and the House of Parliament in the UK, Bleasedale will undoubtedly continue to be a respected voice within the realm of photography, specifically within regions of conflict.

He can be followed on twitter @marcusbleasedale.

ANDREW BRIDGE @Bridgin_TheGap

Andrew is Editor-in-Chief of CATALYST's Social Good Summit Daily, and Managing Editor of CATALYST. He is a global enthusiast with a passion for the road less traveled. As a frequent collaborator with World Hip Hop Market and Nomadic Wax, Andrew has worked with numerous socially conscious artists from around the world in the pursuit of inspiring cultural understanding and exchange through entertainment. This fascination with the world at large has taken him to over 20 countries (so far) through studying, volunteering, and writing about his travels, with no signs of slowing.