The Berlin Wall spent decades as a symbol for ideological division, but has become an outlet for personal expression.

Thierry Noir’s heads at the East Side Gallery. Paul VanDerWerf. CC by 2.0.

Visually, the East Side Gallery in Berlin, Germany is a vast edifice of technicolor concrete. Although only fragments of the original 96 mile (155 kilometer) wall remain, the sections that still stand are striking. From the flashes of aquamarine and mustard yellow featured in Thierry Noir’s iconic cartoon heads to the dark spray paint outlining miscellaneous graffiti, the murals are simultaneously imposing and welcoming. But the gallery's importance runs deeper than its appearance; decades of history and political turbulence echo through its fallen walls.

When fully intact from 1961 until 1989, the Berlin Wall separated East Berlin from West Berlin; both halves were located well within East German territory, making West Berlin a NATO exclave in the Eastern Bloc. Prior to the wall's construction, emigration to West Germany by skilled workers, professionals, and intellectuals threatened East Germany’s economy. A few years after World War II, East Germany was constituted as a communist state controlled by the Soviet Union, while West Germany was formed out of the French, British and American occupation zones. The wall became a physical symbol of the Cold War: a division not only of Europe geographically, but also the global ideological divide between communism and democracy.

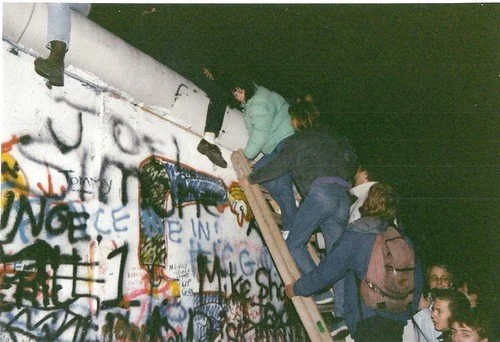

In the midst of longstanding Soviet de facto control of East Berlin, in 1985 then-Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev introduced the reform policies of glasnost (“openness”) and perestroika (“restructuring”), referring primarily to freedom of expression and economic reform, respectively. This decision, coupled with the growing number of protests sweeping across multiple Soviet republics, created a breaking point that eventually erupted into mass action. On November 9th, 1989, East German spokesman Günter Schabowski announced that East Germans would be free to travel into West Germany, starting immediately. In reality, travel was supposed to commence the following day, with regulations to prevent complete freedom of movement. But it was too late for regulations, and the crowds of people from East Germany immediately began to climb and even physically break down the wall.

The fall of the Berlin Wall, 1989. Gavin Stewart. CC by 2.0.

Because of the long period of repression associated with the barrier, one might assume that civilians who had lived on either side would want nothing to do with it ever again. But in 1990, just months after the Wall fell, some of the most famous murals of the Berlin Wall were painted (some of the preserved graffiti, including Thierry Noir’s brightly-colored heads, was created even before the Wall fell). With a newfound sense of freedom, people found their voice through art and created pointed political, social and cultural commentary.

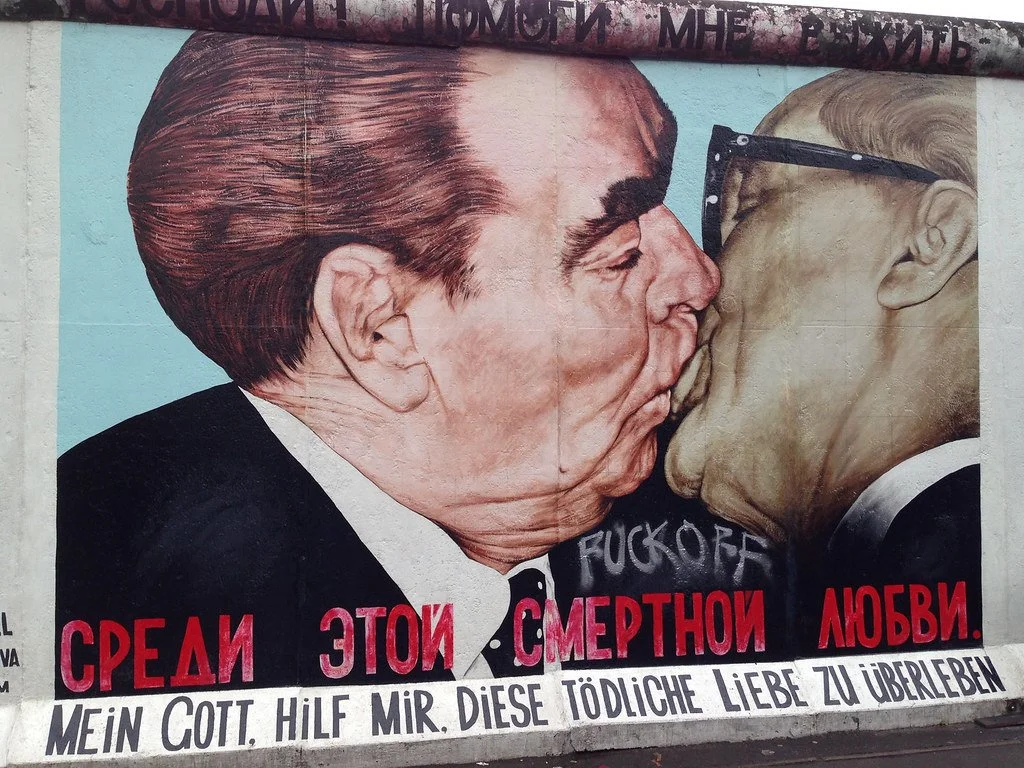

Arguably the most famous of these works is Dmitri Vrubel’s “My God, Help Me to Survive this Deadly Love.” Commonly referred to as “Fraternal Kiss,” Vrubel’s piece depicts East German leader Erich Honecker and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev kissing. The kiss between the two socialist leaders was a rare, but not unknown greeting — often socialist leaders would kiss each other thrice on each cheek after embracing and, at special events, would kiss on the mouth to demonstrate solidarity and brotherhood.

The Brezhnev-Honecker mural was based on a real photograph of the event taken by Regis Bossu eleven years earlier, in 1979. The kiss took place after an economic agreement between the USSR and German Democratic Republic (the formal name of communist East Germany). The image was famous when it was originally taken, but Vrubel’s artistic rendering took its notoriety to new, unforeseen heights.

“My God, Please Help Me Survive this Deadly Love.” Andy Hay. CC by 2.0.

Although Vrubel’s iconic piece is perhaps the most recognizable mural, much of Berlin’s wall art would not have been painted without the help of Kani Alavi. Alavi was an organizer of the East Side Gallery, which invited artists from around the world to paint and express their reflections on the Cold War ideological divide and personal experiences. Alavi’s own visual contribution, “It Happened in November,” is a synthesis of personal experience and political commentary. The Berlin Wall consisted of two distinct walls separated by a gap for maximum security, and Alavi’s mural depicts thousands of faces walking between them on the day it came down. Alavi had viewed this scene personally from his apartment overlooking Checkpoint Charlie, which was the best-known border crossing between East and West Berlin.

“It Happened in November.” Fraser Mummery. CC by 2.0.

Alavi also directly helped inspire another of the most notable murals, the “Berlin Wall Trabant” by artist Birgit Kinder. Supposedly, Alavi told Kinder to paint anything she wanted on the wall, but she hesitated for a moment. It was only when she looked at her East-German manufactured Trabant car that she felt inspired. She began painting her car forcefully bursting through the wall, symbolizing the city’s escape from Soviet rule. Close observers will note that the license plate reads “Nov 9-89,” which is the day the Berlin Wall fell.

“Berlin Wall Trabant.” Judith. CC BY-NC 2.0.

When the wall fell, and the Soviet grip on East Germany loosened, creativity flowed. Artists visually translated their newfound freedom onto a canvas that had once held them captive. Their murals symbolized the reclamation of power by East Berlin’s formerly oppressed inhabitants. And with this somewhat-unlikely canvas they were able to recount their lived experience and depict the conflict and compromise of the world around them, concretely living in vivid color, forever.

Carina Cole

Carina Cole is a Media Studies student with a Correlate in Creative Writing at Vassar College. She is an avid journalist and occasional flash fiction writer. Her passion for writing overlaps with environmentalism, feminism, social justice, and a desire to travel beyond the United States. When she’s not writing, you can find her meticulously curating playlists or picking up a paintbrush.