Coober Pedy is a small desert town in Australia where the entire population lives in underground homes. With outside temperatures hovering over 100 degrees, residents made permanent homes in the cooler temperatures of old mine shafts.

Into the Outback

An epic and ancient landscape, deeply entwined with the artistic, musical, and spiritual traditions of Indigenous Australians, the Outback is one of the largest remaining, intact natural areas on Earth. A cultural, ecological, and geological wonder, I explore and capture these vibrant regions on foot and from the air.

Known for its Aboriginal peoples and its vast, ancient landscapes, the Outback is an incredibly special place for me. I think that once you get that distinctive red dust in your blood it never comes out.

My roots are deeply connected to the rural areas of western Queensland and from a very young age, the never-ending expanse of inland Australia has been something that has captivated me. Ever since I can remember, we would take long road trips out to a family-run cattle station, and there was always this great sense of wonder and adventure. In the Outback, you can travel for days in any direction and stumble across places that are unique, untouched, and rarely visited. It was on these early trips that I fell in love with the bush, the people, and its landscape. I’ve never stopped venturing back.

Pannawonica Hill, near the small town of Pannawonica, a tiny iron-ore mining settlement in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. // © Dan Proud

Drawn to remote, wide open spaces, to the dusty and the desolate, I have found that there are countless unique rocky outcrops and ridges to explore. From the arid and ancient regions of Kimberly and Pilbara in Western Australia, to the rugged, weathered peaks and dramatic rocky gorges found in the Flinders Ranges of South Australia, to the red centre and Australia’s most famous monolith, Uluru — it is not only the sheer size of the Outback that is astounding (it could encompass almost all of Europe), it is also home to some of the world’s most spectacular and untouched landscapes. Over the past few years, I’ve been lucky enough to photograph, film, and fly over these regions — both in light aircraft, and more recently, with drones.

The West MacDonnell Ranges, known as the West Macs, seen from the air. Found in Australia’s Red Centre, west of Alice Springs. // © Dan Proud

Deeply entwined with the landscape itself are the artistic, musical, and spiritual traditions of the Indigenous Australians, among the longest surviving cultural traditions in human history. Some 30,000 to 70,000 years ago — many millennia before the European colonisation that would come to threaten and profoundly disrupt many Aboriginal communities — the first inhabitants of Australia arrived from the north, making them amongst the world’s earlier mariners. They spread throughout the landmass, surviving even the harsh climatic conditions of the Last Glacial Maximum.

Evidence of ancient Aboriginal art is found all over the Outback, most notably at Uluru and Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory. An impressive sandstone rock formation, Uluṟu — as it called by the Pitjantjatjara Anangu, the Aboriginal people of the area — or Ayers Rock, still holds great sacred and cultural significance for the local indigenous population. Appearing to change color at different times of year, this natural monolith is quite magnificent as it glows a deep red or purple at sunrise and sunset.

Uluru, or Ayers Rock, the huge sandstone monolith in Australia’s Red Centre, glows deep red at sunset. // © Dan Proud

It was only in 1606, little over four centuries ago, that the first known European landing was made by Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon on the western shore of Cape York, in Queensland. This discovery was closely followed by that of Dirk Hartog, another Dutch explorer, who sailed off course during a voyage in 1616 and landed on what is now known as Cape Inscription, thus discovering the coast of Western Australia.

For many decades to come, the true extent of the continent would not be known, and with the exception of further Dutch visits to the west, Australia remained largely unvisited. Although a number of shipwrecks are evidence that other Dutch and British navigators did encounter the coast during the 17th century, usually unintentionally, it would be over 150 years before the crew of HMS Endeavour, under the command of British explorer Lieutenant James Cook, sighted the east coast of Australia in 1770 and Europeans widely came to believe that the great, fabled southern continent existed.

Trees in stark contrast with the vibrant orange of Uluru, or Ayers Rock. // © Dan Proud

Running in parallel ridges to the east and west of Alice Springs, through Australia’s Red Centre, lie the East and West MacDonnell Ranges, also known as the Macs. Most people imagine the Outback to be completely flat, but these mountains run for more than 600 kilometres and in places reach heights of over 1,500 metres. Formed 300 to 350 million years ago, folding, faulting, and erosion have since shaped the Macs to form numerous narrow gaps and gorges, and they contain many areas of cultural significance. Seen from the air, their undulating and intricate rock formations are spectacular.

The West MacDonnell Ranges seen from the air, in Australia’s Red Centre, west of Alice Springs. // © Dan Proud

Weather patterns in the Outback are also something that surprises many people. While often envisaged as a uniformly arid area, the Outback regions stretch from the northern to southern Australian coastlines, and encompass a number of climatic zones — including tropical and monsoonal climates in northern areas and temperate climates in the southerly regions. At times, dramatic dust and thunder storms roll in, soaking the dry ground and often causing flash flooding. Witnessing these storms is an incredible experience.

Dust and thunder storm meet near the tiny settlement of Innamincka, Southern Australia. Situated on the banks of Cooper Creek, it is surrounded by the Strzelecki, Tirari and Sturt Stony Deserts. // © Dan Proud

Reflecting its wide climatic and geological variation, the Outback contains a number of distinctive and ecologically-rich ecosystems, along with many well-adapted animals, such as the red kangaroo, the emu, and the dingo, which are often to be found hidden in the bushes to keep cool during the heat of the day. Recognised as one of the largest remaining, intact natural areas on Earth, the Outback is home to many important endemic species.

One such species is Adansonia gregorii, known locally as the boab tree, which is found nowhere else in the world but the Kimberley region of Western Australia, and east into the Northern Territory. With their striking swollen trunks, boab trees can reach up to five metres in diameter at their base, and amazingly, some individual trees are more than 1,500 years old, making them the oldest living beings in Australia, and among the oldest in the world.

For thousands of years, Indigenous Australians have used these giants for shelter, food and medicine; often collecting water from hollows within the tree, and using the white powder that fills the seed pods as food. Decorative paintings or carvings were also made on the outer surface of the fruit.

A boab tree growing in the Kimberly region of Western Australia. // © Dan Proud

Also found in the Kimberly region is the Cockburn Range, a magnificent sandstone escarpment that rises for 600 metres above the surrounding plains. Shaped like a vast fortress with towering orange cliffs, many rivers have cut through the formation to form steep-sided gorges. Flying above the Range at sunset, when the western face is lit up with a brilliant red glow, reveals another of the Outback’s epic and ancient landscapes.

Sunset flight over the Cockburn Ranges in Kimberley, Western Australia. // © Dan Proud

The geology of South Australia’s Outback is no less dramatic, and among the rugged, weathered peaks and rocky gorges of the Flinders Ranges, some of the oldest fossil evidence of animal life was discovered in 1946, in the Ediacara Hills. Similar fossils have been found in the Ranges since, but their locations are kept a closely guarded secret to protect these unique sites.

Cast in golden light, Bunyeroo Valley in Southern Australia. // © Dan Proud

The first humans to inhabit the Flinders Ranges were the Adnyamathanha people — meaning “hill people” or “rock people” — whose descendants still reside in the area, and also the Ndajurri people, who no longer exist. Cave paintings and rock engravings tell us that the Adnyamathanha have lived in this region for tens of thousands of years. Though my perspective is usually broad and from the air, in the nooks and crannies of these arid landscapes live the yellow-footed rock-wallaby, which neared extinction after the arrival of Europeans due to hunting and predation by foxes, and also two of the world’s smallest marsupials — the endangered dunnart, and the nocturnal, secretive planigale, smallest of all, often weighing less then five grams.

The dramatic Flinders Ranges of Southern Australia seen from above, photographed by drone. // © Dan Proud

Last but certainly not least, we come to the spectacular Pilbara region of Western Australia. Stretching over a vast area of more than 500,000 square kilometres in the north of Western Australia, it is home to some of Earth’s oldest rock formations, dating back an impressive two billion years.

Seen from the air, parts of the Pilbara can sometimes resemble another planet. Yet the greens and yellows of the acacia trees, the hardy shrubs, and the drought-resistant Triodia spinifex grasses — contrasting so spectacularly with the brilliant orange and ochre of the land itself — remind us that life can flourish and adapt even in the most challenging of conditions.

The vibrant colors and unusual contours of the mineral-rich Pilbara landscape in Western Australia. // © Dan Proud

Known also for its vast mineral deposits, for many years the Pilbara has been a mining powerhouse for crude oil, natural gas, salt, and iron ore. Today, although the fragile ecosystems of this area have been damaged by these extractive industries, a number of Aboriginal and environmentally sensitive areas now have protected status in the Pilbara — including the stark and beautiful Karijini National Park with its deep gorges and striking canyons.

Stunning displays of rock layers at Hancock Gorge in the Pilbara. // © Dan Proud

Culturally, Australia’s Outback regions will always be deeply ingrained in our country’s heritage, history, and folklore. For Indigenous Australians, creation of the land itself is believed to be the work of heroic ancestral figures who traveled across a formless expanse, creating sacred sites on their travels. Ecologically, it is one of the most untouched and intact natural areas we have left on the planet, and home to a plethora of important endemic species. Geologically, it represents a vast and ancient landscape — one of the most unique on Earth and one that I could never tire of exploring. Every time I head up into the air or set out to photograph the Outback, I’m blown away.

Dotted with acacia trees, the striking landscape of Pilbara’s Outback region at dusk. // © Dan Proud

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON MAPTIA.

DAN PROUD

Dan Proud is a Queensland-based photographer and film maker with a passion for aerial cinematography and capturing the magical wide open spaces of Australia.

Flip Your Map and Up Your Impact

Part 1 of a 2-part series on Maps

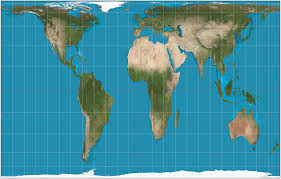

The map of the world.

When we look at the most commonly-seen map of the world, we assume that it depicts the earth as it truly is. But this particular projection of the world, like all others in existence, isn’t completely accurate, as it is impossible to avoid distortions when translating three dimensions into two. Known as the Mercator projection, this map was designed for navigation but distorts relative size, artificially enlarging land masses further from the equator. The result is more severe than you might imagine: Africa appears smaller than Greenland, when it is actually fourteen times larger. See this for yourself here.

There are many other, less common projections which you can explore here. Some are equal area projections, such as Gall-Peters, which manage to avoid the relative size distortion of Mercator but are then much less useful for navigation and less accurate with regard to shape. While the Mercator projection has been abandoned by atlases in favor of projections with more balanced distortion profiles, it is still used by popular online navigation tools such as Google Maps given its navigational prowess (unless you happen to be exploring one of the poles, where it is practically useless).

Gall-Peters Projection

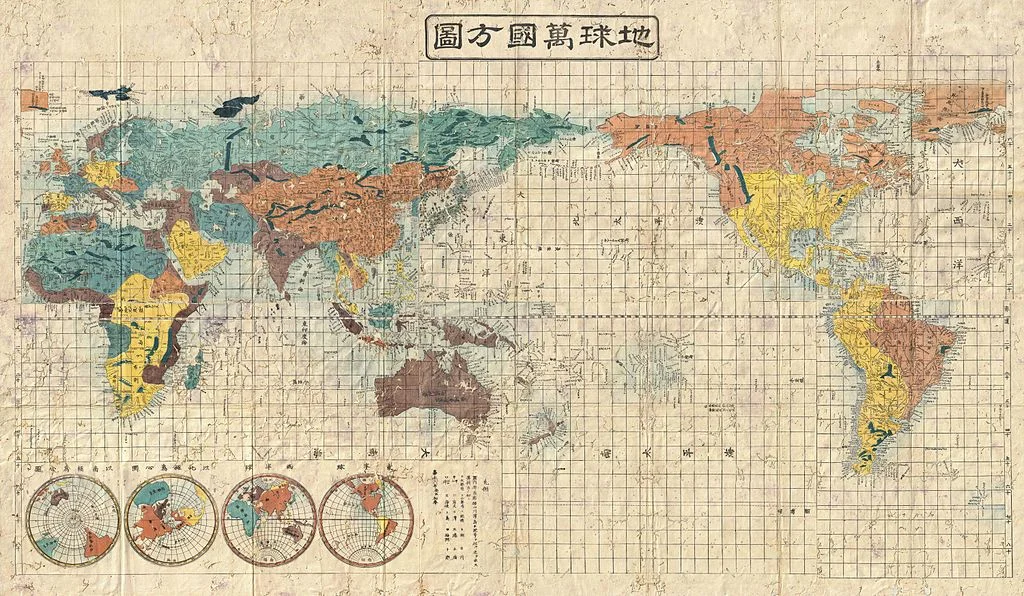

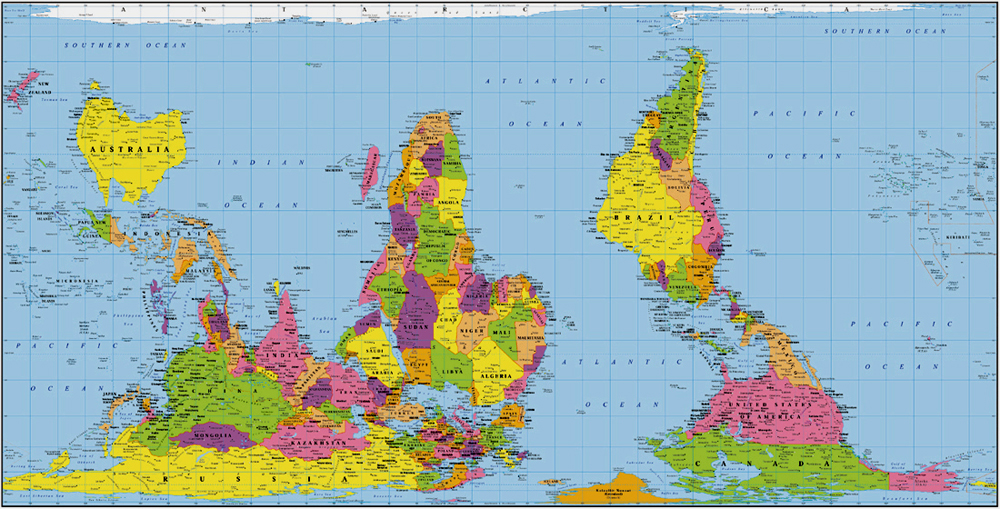

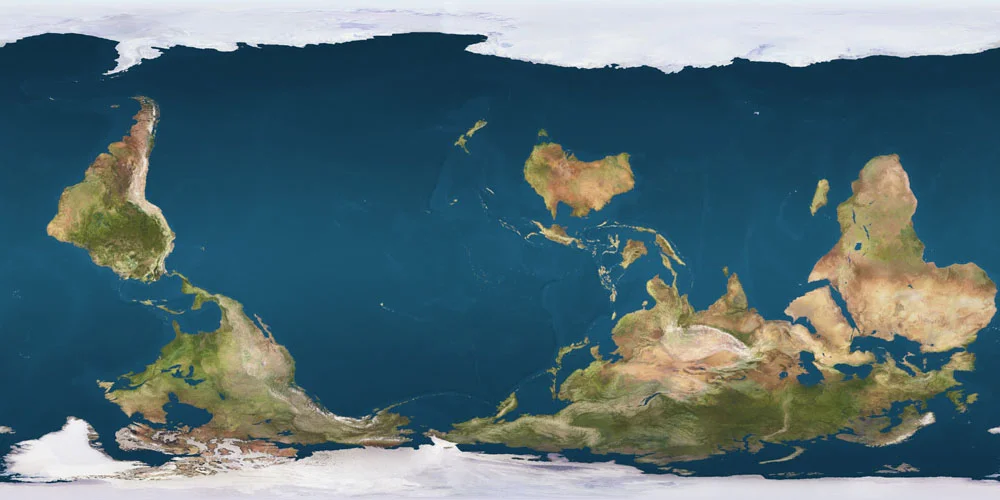

The most commonly-seen map of the world also has a particular orientation and center: north-up and the Atlantic. Yet this framing is neither inevitable nor inherently more correct. Medieval maps were often East-up, Pacific-centered maps pop up in Asia, and a National Geographic feature on the world’s oceans opted to carve up continents instead of bodies of water.

As a result of the complex politics of map-making over time and the inertia of convention, the north-up, Atlantic-centered Mercator projection is the most prevalent, making it not only a navigation tool, but also the image of the world in our mind’s eye. But why does this matter? If all projections are distorted in some way, and orientation, although heavily influenced by historical political jockeying, is ultimately arbitrary, can’t we just continue using it?

There is a big reason why this is not such a great idea: where things are on the map and how big they are in relation to other things affects what we think of them.

Research has shown that we (English-language users) tend to associate up with goodness and down with badness; think about upper and lower class, movement along the socio-economic ladder, “started from the bottom now we’re here”, the assumed location of heaven and hell, and the connotations of uptown and downtown. It has also shown that we tend to associate up with north and down with south (“up north”, “down south”) despite the fact that up/down is an orientation to gravity while cardinal direction is an orientation to the poles. When we are repeatedly exposed to the north-up world map, it reinforces the association of up with north and down with south, and therefore strengthens the association of north with the positive qualities associated with up, and south with the negative qualities associated with down. The popularity of the north-up map makes us more readily associate positive things with northern places.

We also tend to associate things in the center of an image with importance, and large objects with importance and strength. Overall, this means that we tend to equate things that occupy large, upper (northern), central places on the map with goodness, importance and strength; and things that occupy smaller, lower (southern) and peripheral places with badness, insignificance and weakness. It is therefore not surprising that some Australians, Asian states, geographers, educators, and even people on The West Wing have pushed for south-up, Pacific-centric and non-Mercator maps.

Now you might be thinking, but I know that those things don’t always match up! Rwanda has a higher percentage of female Members of Parliament than any other country on earth even though it’s in the Global South! China is hugely important in the global economy even though it’s on the periphery of the map! Israel is powerful even though its relatively small size is exaggerated by its proximity to the equator!

But these mental links, also called implicit associations, are mostly unconscious, and they show up in many areas of our lives even when we consciously know and believe that they aren’t correct. In other words, stereotypes and generalizations affect our decisions and behaviors even though we know they aren't always true. This insight comes from implicit association tests, which show that we are quicker and more accurate at sorting things into bins when the bins match up with unconscious associations in our brains, even when we report not having these associations. For example, when sorting words or images that are often perceived as fitting into just one of four categories - fat, skinny, good, bad - we tend to be faster and more accurate when we are putting items that we perceive as fat or bad into one box, and items that we perceive as skinny or good into the other box. We are on average slower and more likely to mess up when we instead have to sort into a box for skinny or bad items, and a box for fat or good items. And this happens even when we report that we don’t believe fatness is inherently associated with badness, or skinniness with goodness. See this for yourself by taking multiple versions of this test.

The most probable explanation for this phenomenon is that it's an evolutionary remnant, which in the earlier days of humanity helped to keep us alive by allowing us to quickly distinguish between safe and unsafe through stereotyping. But the modern-day implication is clear: even if we don't explicitly think that northern, central, or large countries are better, stronger and more important, associations between these categories probably lurk in our psyches. Where things are on the map and how big they are in relation to other things affects what we think of them regardless of whether or not we realize it’s happening. We don’t just shape maps, maps shape us.

These mental links may seem harmless, but researchers have suggested that implicit associations in general contribute to everything from childcare expectations for different genders to police brutality against people of color. They affect decisions like whether or not to cross the street when we see someone walking towards us, where to travel, and which deaths from terrorist attacks to change our profile pictures for.

The particular mental links created and reinforced by this map aren’t harmless either, as they correlate with current and historical global patterns. And when these mental links line up with what’s happening in the world, they perpetuate each other. Although it is sometimes quite handy that associations from our dominant map match reality, it is also limiting, as we tend to see characteristics of certain places as natural and normal, and the resulting global power dynamic as inevitable. For instance, this map and the associations it fortifies make it harder for us to imagine a world where the West (a confusing term generally used to refer to Northwestern Europe, the US and Canada) isn’t the most powerful and important group of countries. When we see things as inevitable and can’t fathom a different reality, we are less likely to intervene to change the course of history. We cannot go somewhere that we have not first traveled in our minds, and with maps reinforcing the status quo instead of igniting our imagination of how the world could be, we are more likely to perpetuate global systems of oppression.

The mental links reinforced by repeated exposure to this map don't just prevent us from taking action, they can also lead us to take part in less-than-ideal action. For example, this particular map reinforces the belief that the West is inherently good and that all countries should strive for our way of life. This belief then informs actions in many sectors, from foreign policy to international development, often resulting in detrimental outcomes for people and planet. Individually, we are encouraged to engage in well-intentioned efforts such as teaching English, which, instead of indisputably beneficial, can be seen as an effort to make “them” more like “us”. Beliefs arising from the associations this particular map reinforces don’t just prevent us from changing things, they support harmful things happening right now.

Instead of being held back by exclusive familiarity with only one of an infinite number of possible projections of earth, we can improve our chances of having a genuinely positive impact by changing our maps. We can continue to use Mercator projections for navigational purposes, but we should switch it up for non-navigational purposes. When hunting down the exact location of a current event you’re reading about, scroll over a pole in Google Earth to flip the world upside down. If you’re buying a world map poster to plan your next trip or track where you’ve been, consider a Gall-Peters projection, south-up or Pacific-centered map; all are relatively easily to find online.

Over time, as you expose yourself to different maps, your mental maps will shift, decreasing the power of certain associations and helping you combat your unconscious internal bias. While daily exposure to our culture and language makes it very hard to de-link up from good, and large and center from important and powerful, changing your maps can delink north from goodness, Africa from weakness, and Small Island States from insignificance (they are, after all, a key climate change frontline). Switching between maps will also remind you that the map is not the territory, and that all maps simultaneously obscure and illuminate. We can also expose ourselves to stories and other media that contradict these associations, a tactic which has been shown to reduce bias when measured with implicit association tests. Purposefully and regularly exposing yourself to other perspectives is also a good life practice, especially for people of privilege, and one of the things travel is perfect for.

SARAH LANG

Instigated by studies in Sustainable Development at the University of Edinburgh, Sarah has spent the majority of her adult life between 20+ countries. She is intrigued by the global infrastructure that produces inequality and many interlocking revolutionary solutions to the ills of the world as we know it. As a purposeful nomad on a journey to eradicate oppression in all its forms, she has worked alongside locals from Sweden to Zimbabwe. She is a lover of compassionate critique, aligning impacts with intentions, and flipping (your view of) the world upside down.