Gen Z, those currently ages 11-25, have been using the Internet and social media all their lives. More informed about social issues through Instagram and TikTok, they are also more vulnerable to misinformation as much content on such platforms is not fact-checked or verified.

Read MoreLooking out at a courtyard in the Grand Mosque of Paris. Gwenael Piaser. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Countries Around the Globe Continue to Legalize Islamophobia

At the beginning of March, independent rights expert Ahmed Shaheed addressed the United Nations Human Rights Council, underscoring the rise in anti-Muslim hate globally and urging member-states to take action immediately. Shaheed noted that in 2018 and 2019, four in 10 Europeans held a negative view of Muslims, and in 2017 30% of Americans held the same negative view.

But in the following weeks, Islamophobic legislation—laws which seek to discriminate against Muslims—were proposed or enacted in countries like France and Sri Lanka, showing just how widespread the situation remains.

France has a long-standing history of Islamophobia. The country, with a Muslim community of 4.4 million, or 8.8% of the country’s population, maintains the largest Muslim community of any Western nation. Over the past decade, the country banned the wearing of niqabs, veils which cover one’s face, in public, several coastal cities banned burkinis, a form of swimwear, and more recently, the French Senate voted to ban anyone under the age of 18 from wearing a hijab.

While protests have met each of these pieces of legislation, with the recently proposed hijab ban seeing demonstrators take to the streets around the country, Islamophobia has been disturbingly commonplace. The number of Islamophobic attacks in France increased by 53% in 2020.

Sri Lanka, a South Asian country whose Muslim community constitutes 9.7% of its population, has had a more recent problem with Islamophobia. While several one-off Islamophobic attacks took place throughout the 2010s, the government only recently began to write Islamophobia into law. In March, the country banned the wearing of the burqa and closed over 1,000 Islamic schools.

The United States is also no stranger to Islamophobia. Throughout the 2010s, states ranging from Arizona to Florida to South Dakota passed 22 anti-Muslim laws. At the federal level, the Trump administration authorized several Muslim travel bans and used Twitter to perpetuate an equivalency between Islam and terrorism.

While bigotry against any religion has existed since the beginning of religion itself, Islam has increasingly been the target of xenophobia globally due to the Sept. 11 attacks, the rise of the Islamic State group in the Middle East and other terror attacks in the West carried out by Islamic extremists.

Regardless of its origins, Islamophobia remains one of the most pressing social justice issues to address in the 21st century. As U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said in a March 2021 video commemorating the International Day to Combat Islamophobia: “We must continue to push for policies that fully respect human rights and religious, cultural and unique human identity … As the Holy Quran reminds us: nations and tribes were created to know one another.”

To Get Involved:

To raise awareness about the recently proposed French hijab ban, sign “Hijab Ban France,” a petition urging the French government to revoke the ban, by clicking here.

To find out about more opportunities globally and locally to get involved in the fight against Islamophobia, check out the Council on American-Islamic Relations and the European Network Against Racism, both organizations taking intersectional approaches to combat Islamophobia through legislative and social means.

Jacob Sutherland

Jacob is a recent graduate from the University of California San Diego where he majored in Political Science and minored in Spanish Language Studies. He previously served as the News Editor for The UCSD Guardian, and hopes to shed light on social justice issues in his work.

Anti-Asian Hate Spreads Across the Western World

In the past year, hate crimes against Asian Americans have risen 149%. But attacks are also growing around the world, here CATALYST reports on incidents in Spain (where 2.9% of citizens of Asian descent have experienced hate crimes), Scotland, Canada and Australia.

Read MoreIn Dr Seuss’ Children’s Books, a Commitment to Social Justice That Remains Relevant Today

On February 18, Random House announced the discovery of What Pet Should I Get?, an unpublished – and heretofore unseen – picture book by Dr Seuss. The announcement came 10 days after the same publisher revealed that it would publish Harper Lee’s “discovered” manuscript for Go Set a Watchman in the summer of 2015.

In What Pet Should I Get? – released this week – the very same siblings who first appeared in One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish now struggle with the question of what pet they should choose.

While the siblings in What Pet Should I Get? may not be as familiar as Scout and Jem Finch, Dr Seuss’ new book is the latest addition to a body of work that remains just as committed to social justice as Harper Lee’s famous novels.

From Flit to Horton Hears a Who!

Such matters were not always the chief focus of Theodor Geisel (Dr Seuss’ real name).

In the late 1930s, using the pen name Dr Seuss, Geisel created cockamamie ad campaigns for Flit bug spray. During the early years of World War II, he contributed notoriously vicious caricatures of the people and leaders of Axis nations for the Popular Front tabloid PM. After joining famous Hollywood director Frank Capra’s Army Signal Corps unit in 1943, he co-created propaganda films under Capra’s tutelage.

However in the years after the war, Dr Seuss’ art underwent a radical thematic shift. With a flood of eager baby boomer readers, he decided he wanted to speak to the perspective of children.

A Flit advertisement proof from the 1930s, drawn by Dr Seuss. Special Collection & Archives, UC San Diego Library

A Flit advertisement proof from the 1930s, drawn by Dr Seuss. Special Collection & Archives, UC San Diego Library

The racist caricatures of Japanese civilians and soldiers that Dr Seuss published in PM had drawn on the social prejudice and aggression that Geisel believed lay at the heart of adult humor. So Geisel entrusted Dr Seuss’ postwar art to the belief that children possessed a sense of fairness and justice that could transform their parents’ world.

Geisel described his 1954 children’s book Horton Hears a Who!, in part, as an apology to the Japanese people his propaganda had demeaned during the war. In subsequent children’s books, he began addressing the major issues of the 20th century: civil rights in The Sneetches (1961), environmental protection in The Lorax (1971) and the nuclear arms race in The Butter Battle Book (1984).

The zany wisdom of Dr Seuss

In 1960, Geisel spelled out the stakes of his art:

In these days of tension and confusion, writers are beginning to realize that Books for Children have a greater potential for good, or evil, than any other form of literature on earth.

Like To Kill a Mockingbird, One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish was published in 1960. And like Mockingbird, the conflicts, tensions and fears of that era are highlighted (albeit indirectly).

One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish follows a brother and sister who encounter a series of increasingly fantastic creatures. Nonsensical skits and slapstick gags disrupt the children’s need to decide on a definitive taxonomy – numbers, colors, oppositions, emotional dispositions – for these animals.

A question nearly all children face. Random House

A question nearly all children face. Random House

The array of sorting mechanisms communicates the siblings’ attraction to different, ever-stranger living things. The book introduces more than a dozen creatures and each is outlandishly distinctive. Most importantly, the children value all of them because of their uniqueness.

Overall, this tale of inclusivity cultivated an appetite for diversity and a delight for change. It rejected the stereotypical ways of regarding persons and things through strict categorization.

Dr Seuss engaged 1960s unrest more directly in Green Eggs and Ham, also published in 1960. Using visual and verbal eloquence, Dr Seuss forces the the adult, Grinch-looking creature to confront his stubborn prejudice against green eggs and ham: the character is presented with a series of challenging questions designed to expose the absence of any foundation for his bias.

The adult remains stubborn in his intolerance until his much younger counterpart convinces him that there’s no more basis for his distaste for green eggs and ham than the dislike he’s taken to Sam-I-Am.

The 650 million children who have read Dr Seuss’ books have been exposed to new ways of viewing the world, of rethinking a social order often imbued in prejudice. But adults continue to use the themes of One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish. It has inspired a CEO’s leadership manual, a Barnes & Noble e-readerand the name of a dating website. The book was quoted by Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan in a dissenting opinion earlier this year.

In 1994, Johnny Valentine and Melody Sarecky even applied it to promote same-sex marriage in their children’s book One Dad, Two Dads, Brown Dad, Blue Dads.

An original sketch from What Pet Should I Get? discovered in Dr Seuss’ home office in La Jolla, California. Dr Seuss Enterprises

The pet shop that provides the setting for What Pet Should I Get? is inhabited by creatures that display striking resemblances to Horton, the Whos and the Sneetches, along with Sam-I-Am and the fish protagonists of One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish. An offshoot of the social vision informing these narratives, What Pet Should I Get? won’t disappoint Dr. Seuss’ readers in the way the Atticus Finch disappointed some To Kill a Mockingbird fans.

As older readers relive their response to a universal question nearly all children face, What Pet Should I Get? will allow a new generation of readers to discover why Dr Seuss remains forever relevant.

Donald E Pease is a Professor of English, Dartmouth College

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

"Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed, citizens can change the world. Indeed it is the only thing that ever has." -Margaret Mead

Ilhan Omar, a Somali American, who was elected from Minnesota’s 5th congressional district, will be the first woman in U.S. Congress to wear a hijab. AP Photo/Jim Mone, File

Three Things We Can Learn From Contemporary Muslim Women’s Fashion

Major art museums have realized there is much to learn from clothing that is both religiously coded and fashion forward.

Earlier this year the Metropolitan Museum of Art hosted a fashion exhibition inspired by the Catholic faith titled “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and Catholic Imagination.” With more than 1.6 million visitors, it was the most popular exhibit in the Met’s history.

And now the de Young Museum of San Francisco has the first major exhibit devoted to the Islamic fashion scene. “Contemporary Muslim Fashions” displays 80 swoon-worthy ensembles – glamorous gowns, edgy streetwear, conceptual couture – loosely organized by region and emphasizing distinct textile traditions. This exhibit is a bold statement of cultural appreciation during a time of heightened anti-Muslim rhetoric.

In studying how Muslim women dress for over a decade, I realized a deeper understanding of Muslim women’s clothing can challenge popular stereotypes about Islam. Here are three takeaways.

1. Modesty is not one thing

While there are scattered references to modest dress in the sacred written sources of Islam, these religious texts do not spend a lot of time discussing the ethics of Muslim attire. And once I started to pay attention to how Muslims dress, I quickly realized that modesty does not look the same everywhere.

Streetstyle in Iran. Contemporary Muslim Fashions 22 September 2018 - 6 January 2019 de Young Museum

I traveled to Iran, Indonesia and Turkey for my research on Muslim women’s clothing. The Iranian penal code requires women to wear proper Islamic clothingin public, although what that entails is never defined. The morality police harass and arrest women who they think expose too much hair or skin. Yet even under these conditions of intense regulation and scrutiny, women wear a remarkable range of styles – from edgy ripped jeans and graphic tees to bohemian loose flowy separates.

Indonesia is the most populous Muslim nation in the world, but Indonesian women did not wear head coverings or modest clothing until about 30 years ago. Today local styles integrate crystal and sequin embellishments. Popular fabric choices include everything from pastel chiffon to bright batik, which is promoted as the national textile.

When it comes to Turkey, for much of the last century authorities discouraged Muslim women from wearing pious fashion, claiming these styles were “unmodern” because they were not secular. That changed with the rise of the Islamic middle class, when Muslim women began to demand an education, to work outside the home and to wear modest clothing and a headscarf as they did so. Today local styles tend to be tailored closely to the body, with high necklines and low hemlines and complete coverage of the hair.

Local textiles in Indonesian fashion.Contemporary Muslim Fashions 22 September 2018 - 6 January 2019 de Young Museum

A stunning range of Muslim fashions are found here in the United States as well, reflecting the diversity of its approximately 3.45 million Muslims. Fifty-eight percent of Muslim adults in the U.S. are immigrants, coming from some 75 countries. And U.S.-born Muslims are diverse as well. For instance, more than half of Muslims whose families have been in the U.S. for at least three generations are black.

This diversity provides the opportunity for hybrid identities, which are displayed through clothing styles.

Tailored trench from Turkey. Contemporary Muslim Fashions 22 September 2018 - 6 January 2019 de Young Museum

This diversity provides the opportunity for hybrid identities, which are displayed through clothing styles.

2. Muslim women don’t need saving

Many non-Muslims see Muslim women’s clothing and headscarves as a sign of oppression. It is true that a Muslim woman’s clothing choices are shaped by her community’s ideas about what it means to be a good Muslim. But this situation is not unlike that for non-Muslim women, who likewise have to negotiate expectations concerning their behavior.

In my book, I introduce readers to a number of women who use their clothing to express their identity and assert their independence. Tari is an Indonesian college student who covers her head at her parents’ objections. Her parents worry that a headscarf will make it harder for Tari to get a job after graduation. But for Tari, whose friends all cover their hair, her clothing is the primary way she communicates her personal style and her Muslim identity.

Nur, who majored in communications at Istanbul Commerce University, dresses modestly but is highly critical of the pressure she sees the apparel industry putting on Muslim women to buy brand-name clothing. For her, Muslim style does not have to come with a high price tag.

Leila works for the Iranian government and considers her off-duty clothing choices a form of civil disobedience. Monday through Friday she wears dark colors and long baggy overcoats. But on the weekends she pushes the limits of acceptability with tight-fitting outfits and heavy makeup – sartorial choices that might get her in trouble with the morality police. She accepts the legal obligation to wear Islamic clothing in public, but asserts her right to decide what that entails.

Designers have also used clothing to protest issues affecting their communities. The de Young exhibit, for example, includes a scarf by designer Céline Semaan to protest against Trump’s travel ban. The scarf features a NASA satellite image of several of the countries whose citizens are denied entry to the U.S , overlaid with the word “Banned.”

Fashion to confront social issues.Contemporary Muslim Fashions 22 September 2018 - 6 January 2019 de Young Museum

Banned headscarf by Céline Semaan. Contemporary Muslim Fashions 22 September 2018 - 6 January 2019 de Young Museum

3. Muslims contribute to mainstream society

A 2017 Pew survey showed that 50 percent of Americans say Islam is not a part of mainstream society. But as Muslim models and Muslim designers are increasingly recognized by the fashion world, the misperception of Muslims as outsiders has the potential to change.

Muslim models are spokespersons for top cosmetic brands, walk the catwalk for high end designers and are featured in print ads for major labels.

Today clothing inspired by Islamic aesthetics is marketed to all consumers, not just Muslim ones. Take the most recent collection of British Muslim designer Hana Tajima for Uniqlo. In its promotional materials, the global casual wear retailer described the garments as “culturally sensitive and extremely versatile,” clothing for cosmopolitan women of all backgrounds.

To be hip today is to dress in culturally inclusive ways, and this includes modest styles created by Muslim designers and popularized by Muslim consumers. Fashion makes it clear that Muslims are not only part of mainstream society, they are contributors to it.

LIZ BUCAR is an Associate Professor of Philosophy and Religion at Northeastern University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Photo by Quinn Dombrowski

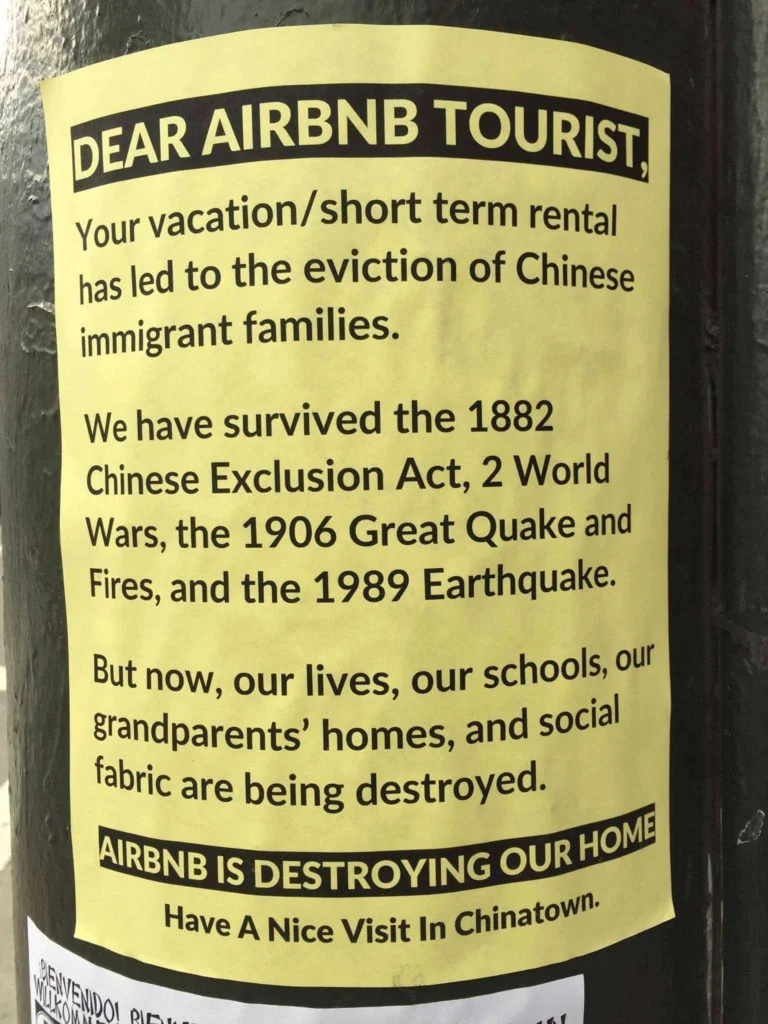

Should one use an airbnb?

From the consumer’s side, the sharing economy is pretty fucking rad. Anyone who grew up riding in taxis and then suddenly switched to Uber knows why: getting into a cab used to be like stepping into a scene from Mad Max: Fury Road, with drivers who were very frequently about as sane as the War Boys.

Uber drivers, however, depend on good ratings from those riding with them, and as such, have an incentive to not drive like lunatics. Likewise, you as the consumer get rated, so you have an incentive to be on your best behavior.

Consumers get the same sort of benefit with Airbnb: it’s not free, like traveler favorite Couchsurfing, so it doesn’t have the same sketchy feel, and it grants customers the opportunity to stay in actual homes in the neighborhoods they’re visiting, rather than in a generic hotel room.

The problem is that the “sharing economy” manages to conveniently undercut decades of labor laws, housing laws, and civil rights laws in ways that the legal system hasn’t caught up to just yet, which is causing some pretty ugly side effects. Uber deserves attention — it dodges and fights regulations that would apply to other cab companies, underpays its drivers, and leave cities that set a higher standard for them — but for now, we’re just going to focus on Airbnb.

What’s wrong with Airbnb?

Airbnb has two really big problems with it that ultimately stem from the same issue. And to be fair, these aren’t necessarily issues that were created by Airbnb, so much as they are issues that stem from the entire concept of the “sharing economy.”

1. Airbnb is playing by a different set of rules.

I live in the seaside town of Asbury Park, New Jersey, and Airbnb is a thing here: a lot of people will rent out their homes for a weekend to get some extra money, and Airbnb and its competitor VRBO are the simplest ways to do it. This is a tourist town, so the town encourages people to invite tourists into their homes. But some of the larger businesses in town are hotels, and there’s a good number of boutique hotels and BnB’s as well. And while they are large for the town, they aren’t mega-conglomerates like Hilton or Marriott. They’re small businesses. So it’s easy for them to be undercut by Airbnb. A homeowner’s profit margin doesn’t need to be as big as a hotelier’s — they aren’t running a full operation, they’re just trying to make some extra cash.

All of this would be fine — competition makes the market work, etc., etc. But users of websites like Airbnb and VRBO often don’t submit to fire safety and coding regulations that would be required of hotels and regular BnB’s, despite being legally required to. It’s also relatively easy for the Airbnb hosts to dodge paying their taxes, as they’re small enough to fly under the radar. This puts the Airbnb users at an unfair advantage, and it pisses a lot of hotel and BnB owners off.

Airbnb presents themselves as scrappy underdogs fighting big mean corporate hotel chains. When New York hoteliers claimed Airbnb was cutting into their business, Nick Papas, an Airbnb spokesperson told Bloomberg News:

“In fact, without Airbnb many of these travelers wouldn’t be able to visit New York City at all or would have cut their trip short. While the big hotels have been clear that they are concerned about losing the opportunity to price gouge consumers, we hope they will disclose the percent of their profits that stay in New York City and the percent they send to corporate headquarters outside of New York and, even, outside of the country.”

But Airbnb is not an underdog — last year, it was valued at $20 billion. That’s in the same league as Hilton ($27.8 billion) and Marriott ($22.9 billion). Since Airbnb isn’t responsible for making sure it’s users are paying taxes and are up to code, it’s basically just playing with the bumpers up.

By presenting themselves as a mere platform connecting people in the “sharing economy,” rather than as the manager of a huge network of small vendors, Airbnb is skirting regulations and making out like bandits.

2. Airbnb may be the reason “the rent is too damn high.”

The publication Grist explained the basics of this problem in a recent article, using the example of Tarin Towers, a resident of a rent-controlled building in San Francisco. Her building was bought by a real estate developer who wanted to charge way more for the rooms, so he offered the residents buyouts. Towers did the math and realized that even with the buyout, she wouldn’t be able to afford a new apartment in the city’s absurdly inflated rental market. From Grist:

“Towers held out as her old neighbors left and new tenants started moving in. Unlike the old neighbors, these new people were young, mobile, transient. And there were a lot of them. [Her landlord] O’Sullivan, it turned out, had leased the building to a startup called the Vinyasa Homes Project. Towers soon discovered that Vinyasa had listed her building on Airbnb, advertising it as a ‘co-creative house.’ The listing made it sound almost like a commune. ‘You want to join a community of like-minded peers who are doing inspirational things?’ it read. ‘This is the place for you.’ Unlike in the communes of yesteryear, however, each bed is going for more than $1,500 a month — and these are bunk beds in shared rooms. That means each apartment could now be bringing in $10,000 a month in rent.”

Towers eventually was forced out of her apartment, and took the buyout. She can’t afford a new rental in the city, so she’s housesitting until she figures something out.

This is a problem everywhere, though: in Barcelona, in Berlin, in New York, in New Orleans. It’s particularly tragic in the Big Easy, as it’s forcing out the last long-term residents who held on in neighborhoods devastated by Hurricane Katrina.

It’s the worst for cities with tight housing markets and a heavy flow of tourists. Remember the New York City mayoral candidate whose platform was “the rent is too damn high”? It may have gotten that high in part because of services like Airbnb — it’s way easier to wait for someone who will pay $2 grand a month for an apartment when you can rent the apartment out for exorbitant prices to travelers in the short term.

Photo by Leigh Blackall

You could argue that Airbnb isn’t responsible for the misuse of its service. But they aggressively fight any measure that would put the onus of responsibility on them. When San Francisco tried to pass a measure that would restrict the number of nights a year a unit could be used for short-term rentals, Airbnb spent $8 million fighting against it. When San Francisco tried to pass a rule that would force Airbnb to ensure its hosts were up-to-code, they donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to local political campaigns.

Some cities have fought back effectively. Barcelona has seen a population drop in its historic neighborhoods thanks in large part to its tourism industry, and as a result, have started slapping Airbnb with fines for offering apartments that weren’t registered with the city, and Berlin and Paris and even New York have been fighting back as well. But this is a problem that’s far from solved.

3. It’s not totally Airbnb’s fault.

In Airbnb’s defense, there’s no good business reason they would voluntarily take responsibility for policing their users. It’s not a charity, and it would be very expensive for them to check up on every single host. It would be a guaranteed way to decrease profits, which, incidentally isn’t legal — companies are required by to take actions that benefit their shareholders.

But this is why we have regulation. Airbnb isn’t tasked with doing what’s best for the local communities: our governments are. So this is a problem that’s fixed not by Airbnb being benevolent, but with good policies and effective enforcement. Which means it’s a battle that needs to be had on a city-by-city and country-by-country basis.

The problem is that we simply don’t know how serious the problem is yet — there’s been a little bit of research, but it’s far from conclusive, and has possibly been biased against services like Airbnb. There’s no reason to think that good policies couldn’t help solve the problems that Airbnb and its “sharing economy” counterparts cause. But more work needs to be done.

So what can we as travelers do?

Let’s be up front: staying at an Airbnb is a cooler experience than staying at a hotel. I have a friend who stayed in a goddamn castle in Italy. I know people who have stayed in treehouses in Oregon and igloos in Norway. In the Netherlands, you can stay in an honest-to-god windmill. And it’s cool that we’re giving regular people this platform to make some extra money, host out-of-town guests, and maybe try something new. So I won’t say “don’t ever stay at an Airbnb or a VRBO.” This is the future, and the solution to its problems will be through systemic change, not through any single individual’s actions. But it’s also time to call bullshit:

There is no such thing as the sharing economy. It’s just called the economy, and it’s been around for millennia.

Are you trading goods and services for cash? Yeah — that’s the economy. You’re just doing it in a different place. Airbnb and Uber haven’t reinvented the economy, they’ve just used the internet to create a new space in which economic transactions can happen.

So with that in mind, here are a couple of things you can to be a part of the solution:

1. Support fair regulation of Airbnb & VRBO in your hometown.

If your town has a lot of tourists, try to be supportive of government attempts to regulate businesses like Airbnb and VRBO. The companies will do shitty ad campaigns about how your city is turning it’s back on money and innovation, but that’s just a scare tactic. Anyone who has lived in a tourist town knows that, even if the economy is dependent on tourist dollars, what’s good for the tourists isn’t always good for the locals. Try and push your local governments to strike a balance between making money and supporting the local community. Get involved. Get organized. This is pretty much always the best solution to anything.

2. Try to avoid the shitty Airbnb hosts.

You can take steps to avoid giving money to the douchebags who are misusing the service. Think of it as another thing you want to research, along with “safety,” “service,” and “cleanliness.” In short, you want to seek out spots that the current owners actually live in.

Becky Caudill over at Casa Caudill has some great tips for spotting the shitty hosts using the platform itself. Here’s what she suggests looking for when you’re checking out the photos of the location provided by the host:

"

- Seek out properties that are decorated like you or your friends would decorate your own homes.

- Look for plants (not just fresh flowers).

- Check out the art. Is everything from Ikea or another mass market supplier? Or are there original prints or photographs on the wall? On shelves? Is there any artwork at all?

- Does the kitchen come with basic supplies like salt, pepper, olive oil, etc? People who live somewhere will have these things on hand. (Although maybe not in NYC? It’s my understanding from friends there that people eat out every night and never cook so maybe they don’t need these things?)

- Do the owners read? Are there books other than travelogues visible in the pics? (And for goodness sake, if you see hundreds of travel brochures that’s a dead giveaway this place is operated solely as a vacation rental property).

- Stay in real neighborhoods, not tourist areas."

It also helps to delve into the comments a bit. Can you get a sense from the comments as to whether this is actually someone’s home, or is it more of an “operation”? Are there big discrepancies between the reports of the rooms? That could be a sign that there are multiple rooms that are lived in by different people in your building, indicating that this is being done by a landlord, not an owner or a tenant.

And of course, if you end up in one of these “operations” in spite of your best efforts, it’s okay: just go onto Airbnb and mention it in the comments. Helping others identify exploitative hosts is as important as helping them identify bigots or creeps. And that’s what the review process is for.

As always, the name of the game is damage control — try your best to support the local communities you’re visiting. Sometimes you’ll fail. Other times you won’t. And don’t assume that all things that are shiny and new are inherently good.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON DON'T BE A DICK TRAVEL.

MATT HERSHBERGER

Matt Hershberger is a writer and blogger who focuses on travel, culture, politics, and global citizenship. His hobbies include scotch consumption, profanity, and human rights activism. He lives in New Jersey with his wife and his Kindle. You can check out his work at the Matador Network, or over at his website.

What are ALL voluntourists good at?

In recent years Voluntourism it has gotten a bad name. There are a lot of valid reasons that people have been turned off by voluntourism, including:

- voluntourism’s potential to foster colonialist attitudes and cause harmful side effects (as in Illich’s thoughts on Peace Corps)

- projects which place unskilled foreign travelers in jobs requiring skilled laborers or taking away local jobs

- short term interactions with children without proper child protection policies (Some argue that English teaching is a great way to engage English-speaking travelers in volunteer work, and perhaps sometimes it is, but I feel that even this is not always a good fit. Often times native speakers know the language, but are not trained teachers and repeated short-term interactions can have harmful side effects for children.)

- volunteer placement agencies charging exorbitant fees from their overseas offices with little to no money reaching the development projects themselves (no need to link to a lot of them for examples, just google “volunteer abroad”!)

These reasons are some of the reasons that I too am skeptical of voluntourism initiatives. I have seen some damaging results of travelers philanthropy which did not embody effective voluntourism or development practices and ended up causing more harm than good. At PEPY, we have made many mistakes ourselves, especially in our first few years of operations where we designed trips for tourists to “teach and give” rather than “learn and support” and where we designed trips around the needs and demands of travelers rather than those of the communities we were working with. Many of our initial mistakes are highlighted in the documentary “Changing the World on Vacation” by Deeda Productions. Although watching some of your mistakes on TV and seeing yourself say some ridiculous things you no longer believe in is not a fun pass time, I appreciative that filmmaker Daniela Kon’s work will serve as a learning tool for many others and reminder to me about the lessons we have learned.

As we have examined at the hands-on service portions of our trips looking to find the most useful way to engage tourists in something they are skilled at, we asked ourselves: What ARE all tourists experts at?

The answer we came up with is this: All tourists are experts at being tourists! Of course!

They know what THEY want when they travel, and that knowledge is often the missing key to successful community based tourism initiatives. Now of course, you and I don’t share the same wants/needs as every tourist and living in Cambodia with a huge child sex tourism industry, I surely wouldn’t want to take the opinions of all tourists to heart when developing new programs. I do though believe that if we find similar minded people looking for an eco-friendly and responsible adventure, one very useful skill they all can bring is the ability to give their feedback and ideas about how to design such a trip.

Tourists can use these skills to help local communities who have a tourism product to offer but are perhaps lacking the experience to market or tailor the trip to tourists. They can also help promote positive environmental practices by highlighting their desire to see natural environments and physical and cultural preservation in the countries they visit.

By matching travelers up with community based tourism initiatives, we hope to improve the whole adventure tourism supply chain by:

- giving thorough feedback and ideas for improvement to community based tourism initiatives and groups looking to offer such products

- offering marketing advice

- promoting positive environmental practices and preservation initiatives

- creating informational and promotional material for the organizations we believe in from signs helping travelers find their way to the site to English language placards or hand-outs describing the locations highlights in areas where English speaking guides might not be available

- Physically helping to improve offerings in the area (constructing signage, cleaning surroundings, beautifying local infrastructure, building safety or protective tools such as fencing or walkways, etc)

We believe that, by designing trips which improve the local adventure tourism supply chain, we can place travelers in a position where both their time and funding are valuable while also helping to ensure that tourism dollars support local initiatives.

We have done some of this in the past, but had not embraced the concept of “using voluntourists as tourists” as much as we currently are in our upcoming tours. Our updated website (coming soon!) will highlight these offerings. In the meantime… what do you think? No, it’s not building a house for a family nor petting kids in an orphanage, so it might not have the same appeal as other offerings, but we believe that if we highlight the added value travelers can bring to responsible (aka. well-vetted) community tourism programs, people will be excited to support these programs.

What do YOU think?

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON LESSONS I LEARNED.

DANIELA PAPI

Daniela is the Deputy Director of the Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship. She has spearheaded student programming initiatives at Saïd Business School including the Leading for Impact programme and had taught on MBA courses including the Entrepreneurship Project and a course on high-impact entrepreneurship. Daniela is a graduate of Saïd Business School's MBA programme and was a Skoll Scholarship recipient.

Prior to coming to Oxford, Daniela spent six years in Cambodia where she grew a youth leadership organization, PEPY, an educational travel company, PEPY Tours, and an advocacy organisation, Learning Service. Daniela is co-authoring a book advocating for a 'Learning Service' approach to philanthropic and volunteer travel and has worked as a consultant to other social impact organizations, typically supporting their strategy redesign by incorporating her experience in social marketing and user-centered programme design. She recently wrote a report called 'Tackling Heropreneurship' focused on fuelling collective impact through an 'apprenticing with a problem' approach.

Check out Learning Service for more.

Together: Ending Child Marriage in Zambia

Mirriam is a 17-year-old who, like any other teenager, has ambitions and dreams. She wants to become a doctor. However, where Mirriam lives, child marriage and poverty threaten her chances of getting the education she needs and the future she dreams of.

Together: Ending Child Marriage in Zambia is a short documentary that asks what can be done to enable girls like Mirriam to avoid child marriage and fulfil their potential?

It tells the story of partnership, of how civil society activists, girls, traditional leaders, and the government are coming together to make sure that no girl is married as a child.

If a movement can gain momentum in a country where rates of early marriage are among the highest in the world, then perhaps we can pave the way for change not only in Zambia but far beyond.

Together: Ending Child Marriage in Zambia shows how by working in partnership we can put an end to child marriage in one generation, and ensure that every girl, like Mirriam, can have a bright future.

This film features the work of Girls Not Brides members in Zambia including the Forum for African Women Educationalists Zambia (FAWEZA), Population Council and YWCA Zambia.

Where is this place we call 'away' when we say 'throw away'?

If you want to make peace with your enemy, you have to work with your enemy. Then he becomes your partner.

IMAGE COURTESY OF ORPHANAGES.NO

Orphanage Volunteering’s Shocking Link to Child Abuse

I never thought that playing catch with a kid could be a bad thing, or that goofing off could contribute to long-term psychological damage. Even now, as I write it, it all seems a little absurd. Is it really possible that making kids laugh could do permanent harm?

Every year, millions of people travel around the world to volunteer. Orphanages are one of the most popular destinations, and it makes sense. Many volunteers like working with children, often because children are enthusiastic and working with them is very active and “hands on.” Most of the tasks volunteers are given when working with kids are simple, and it is rare that volunteers are expected to have any specialized skills or to participate in any in-depth training before starting their volunteer work.

At the same time, orphanages are often understaffed and poorly kept up. Operating with limited resources (or under the appearance of limited resources), they are frequently on the lookout for people who are willing to pay to work. Placement companies and organizations provide orphanages with paying volunteers to help with childcare, teaching, cooking, and maintenance. Volunteers are told that they’ll be providing orphaned children with a more nurturing environment while orphanages get a steady income and a constant flow of helping hands.

All of this sounds fine and dandy, but the problem with orphanage volunteer work isn’t in the volunteer’s desire to help, but in the very existence and implementation of orphanages themselves.

Not many would-be volunteers realize that more than 80% of children who are labeled as “orphans” have a surviving parent. Even fewer understand that the traditional kinship structures of many non-western countries, especially those where orphanage volunteering is most common, actually result in very few children being left without someone to care for them (Richter and Norman, 2010; UNAIDS/UNICEF/USAID, 2004).

Which begs the question: why are there so many kids in orphanages?

There are orphans that need a home, and sometimes that means that they have to go into group care, but for many of the children who are labeled as orphans and blazoned across brochures, it’s poverty, not a loss of family, that put them there. Desperation will make people do unthinkable things, especially with the promise of ample food, a solid education, and a comfortable bed. Because of this, all around the world caregivers are willingly giving up their children to orphanages. Sometimes, they even get cash in return. This isn’t altruism on the orphanages part, it’s well-disguised human trafficking.

None of this is the volunteer’s fault, but just by working at orphanages, volunteers are contributing to the problem and, inadvertently, may be supporting the exploitation and traumatization of children - the opposite of what their goal was in going to volunteer in the first place.

Once the volunteer arrives at the orphanage, they might get a feeling that something is off, but it’s easy to push that feeling away when there are kids who genuinely do need help regardless of how they got there. The do need attention and love, they do need teachers and caregivers, and when they get those things children, especially young children, are often overwhelming grateful. It’s hard to walk away, and it’s easy to ignore the problems when there’s a kid on your lap, a kid on your back, and another looking for a place to grab onto.

While the industry is definitely shockingly corrupt, there are many orphanages and children’s homes that truly believe that they are acting in their ward’s best interests and are committed to putting the child’s, not the paying visitor’s, needs first. The way children get into an orphanage, and the ongoing exploitation of them once they have arrived, are part of a systemic problem that may not apply to every orphanage. However, there are also more personal impacts of short-term volunteering, relevant across the entire industry, that may be just as harmful.

Three key aspects of child development that most people can agree on are:

- Children benefit from long-term relationships with adult figures.

- Those adults don’t have to be a family member in the traditional sense, but having a stable familial atmosphere promotes positive development.

- Children without stable relationships with adults often suffer from psychological and behavioral issues that are directly related to a lack of stability and guidance early in life.

All three of these are proven concepts that apply around the world from Cambodian orphanages to the American foster care system. Orphanages that rely heavily on free or paying volunteer labor and, as a result, tend to have only a small local staff, act in complete disregard of these three concepts. They drastically reduce the opportunities that their children have to form long-term relationships, they create an unstable environment where people are constantly rotating in and out and, by doing those two things, they are causing psychological damage to the children that they are supposed to be helping.

As a privileged “gringa,” or white girl, who spends time in impoverished communities, I’ve come to realized not only what my presence can mean, but also what it can do. I know that when I was doing short-term volunteer work, I was as much of an exotic distraction to the children I was working with as they were to me. Even when they had the opportunity to form relationships with locals who could serve as role models, it was my presence that was highlighted. I, the person who was going to leave in just a few days, was given all the attention that should have been shined on the heroes who the children were interacting with every day.

Some might argue that this is giving volunteers too much credit since that all they are there to do is help. Any person who has had children climb on top of them in a frenzy for attention, clamor to have their picture taken, or cry in their arms as they prepare to leave, has to admit that they are in a position of immense power. By choosing to support orphanages that rely on volunteer labor, well-meaning volunteers are inadvertently using this power to exacerbate a broken system and disincentivize governments and NGOs from finding lasting systems-based solutions.

Even if the orphanage that you’ve been eyeing looks perfect, short-term volunteering at orphanages feeds a market that trafficks in, exploits, abuses, and permanently traumatizes the very children that you are looking to help. Even in the best of cases, short-term volunteer work, especially unskilled and non-specialized placements, encourage an uneven power dynamic in which the volunteers are held above the locals. They are looked to as benevolent angels, turning the lens away from the men and women who could serve as positive adult role-models for children who desperately need a stable family environment.

I’ve would never have labeled myself as abusive before I volunteered at an orphanage, and I think it’s fair to say that most volunteers would recoil at the suggestion that they could be categorized as abusers. Now that I know what orphanage volunteer does to children, I have to call it out for what it is - abusive and exploitative.

So no, you shouldn’t go. Don’t support orphanage volunteering. Don’t support child abuse.

You can support this effort in two ways:

- Sign the petition calling on travel operators to remove orphanage volunteering placements from their websites.

- Share this post, along with your thoughts on orphanage volunteering, using the hashtag #StopOrphanTrips.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON HUFFINGTON POST.

PIPPA BIDDLE

Pippa Biddle is a writer. Her work has been published by The New York Times online, Antillean Media Group, The FBomb, MTV, Elite Daily, Go Overseas, Matador Network, and more. She is a graduate of Columbia University with a degree in Creative Writing. Twitter: @PhilippaBiddle

VIDEO: A Fisherman's Freedom in Madagascar

Ravelo was trapped; He couldn't afford to continue paying the local loan shark to rent fishing equipment, because he couldn't catch fish to sell and make his payments. He couldn't catch fish because the mangrove estuaries had been depleted of wood for fire, in turn decimating the population of fish and seafood.

When Ravelo was hired by Eden Reforestation Projects, he was not only able to make an income planting trees, but his environment began to revitalize.

Eden Reforestation Projects hired Outskirt Films to tell this story on the remote coast of Madagascar. This powerful story was filmed in Madagascar by Outskirt Films.

VIDEO: People Before Profit

Most development projects, at face value, seem aimed at improving the lives of people. The reality for communities living at or near a project -- be it a dam, a sports complex, or a shopping mall -- is often quite different.

Forced evictions regularly do not uphold obligations to fairly consult, compensate, resettle and rehabilitate communities. An estimated 15 million people are affected each year.

WITNESS, with partners around the world, are bringing the stories of communities facing human rights abuses and forced evictions to the government officials, the courts and corporations who can make change. For more information about this campaign visit www.witness.org

BANGLADESH/INDIA: From No-Man's Land to the Unknown

For decades, more than 50,000 people have been stranded, without access to basic rights, on tiny islands of no-man’s land locked within India and Bangladesh. 2015 finally saw an end to these enclaves, or ‘chitmahals,’ bringing hope and change to communities living on the world’s most complex border.

The party lasted long into the night across remote patches of northern Bangladesh. As the clock struck midnight people played music, danced and sang using candles for light, and for the first time in their villages they raised a national flag. Similar events were also taking place on the other side of the border in India just a stone’s throw away.

For 68 years, ever since the formation of East Pakistan in 1947 (which later became known as Bangladesh), the residents of one of the world’s greatest geographical border oddities have been waiting for this moment; for their chance to finally become part of the country that has surrounded yet eluded them for so many years.

At 12.01am on July 31st, 2015, India and Bangladesh finally exchanged 162 tracts of land — 111 inside Bangladesh and 51 inside India.

Known in geographical terms as enclaves, or locally as chitmahals, these areas can most easily be described as sovereign pieces of land completely surrounded by another, entirely different, sovereign nation.

Inside an enclave, a man prepares jute by removing the long, soft vegetable fibres that can be spun into coarse, strong threads, and keeping the sticks. For many enclave dwellers, jute is where most of their income comes from and also what they use to build their houses.

Enclaves aren’t as rare as you may think, and until now this part of South Asia has contained the vast majority. Existing around the world, mostly in Europe and the former Soviet Union, they were once much more prevalent — until modern day cartography and accurately defined borders eliminated many. Some still remain, such as the Belgium town of Baarle-Hertog, which is full of Dutch territory. The locals have turned the unusual border into a tourist attraction. However, for this region of southern Asia, where political and religious tensions run high, the existence of enclaves is not so jovial. Life for those who are from these areas is far harder than in neighbouring villages, only minutes away.

Sisters Lobar Rani Bormoni, 11, and Shapla Rani Bormoni, 12, stand in a paddy field in the enclave in Bangladesh where they born.

“These enclaves are officially recognised by each state, but remain un-administered because of their discontinuous geography. Enclave residents are often described as “stateless” in that they live in zones outside of official administration — since officials of one country cannot cross a sovereign frontier into administered territory,” explains Jason Cons, a Research Assistant Professor at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas, Austin and author of the forthcoming book, ‘Sensitive Space: Fragmented Territory at the India-Bangladesh Border.’

Muslim men from Dhoholakhagrabari enclave pray in their mosque. Mosques are usually the only solid structures that exist inside the enclaves.

Several folktales tell of the origin of these enclaves being the stakes in a game of chess between two feuding maharajas in the 18th century, or even the result of a drunken British officer who spilt spots of ink on the map he drew during partition in 1947. Captivating as these stories are, the most likely explanation dates back to 1711 when a peace treaty was signed between the feuding Maharajah of Coch Behar and the Mughal Emperor in Delhi. After the treaty their respective armies retained and controlled areas of land, where the local people had to pay tax to the respective ruler, thus creating pockets of land controlled by different people.

Prior to 1947, when this region was entirely Indian territory, living in these locally-controlled enclaves made little difference. However, during the drawing of the boundary between India and Bangladesh, the Maharajah of Coch Behar asked to join India — on the condition that he retain all his land, including that inside the newly formed East Pakistan, which his ancestors had rightly won control of over 200 years ago.

So, through no fault of their own, the lives of 50,000 people turned upside down — for decades they have been stranded on islands of no-man’s land.

A man fishes at dusk using his large bamboo fish trap. This river exists just outside the enclave but as it’s in Bangladesh territory, enclave dwellers are forbidden to fish here otherwise angering the local fishermen.

Enclave dwellers fish in a flooded paddy.

During the early 1970s a framework to find a solution to this problem was put in place — called the 1974 Land Boundary Agreement. For forty years, as governments came and went, neither the Indian nor the Bangladeshi politicians were able to agree with their counterparts at the time. And whilst the politicians squabbled, the residents suffered.

Only informal work, like at this sawmill, is available for enclave dwellers in Bangladesh.

On the ground there are no border fences or security checkpoints, and without realising it, you can walk in and out of India countless times, crossing an international boundary completely obliviously. However, there is a serious lack of infrastructure and this has been one of the most serious problems facing the residents. Paved roads quite literally stop at the boundaries to the chitmahals, as do electricity poles. The enclave inhabitants in Debiganj District of Bangladesh, as non-Bangladeshi citizens, were even barred from sending their children to school, also receiving no state assistance or even the most basic of hospital treatment.

Sheltered within their small bamboo house, located inside the enclave of Dhoholakhagrabari, Eity Rani, 14, and Shobo Rai, 8, carefully do their homework by the light of an oil lamp. Life is much harder for children who are born in enclaves.

A Bangladeshi man sits in a shop in the market of a small town that sits between enclaves.

Every Saturday a jute market is held in Debiganj. For the many inhabitants of the enclaves that surround the town, jute is where most of their income comes from.

Wearing just a lungi — a traditional sarong worn around the waist — Sri Ajit Memo is sitting in the middle of a small muddy courtyard, surrounded by houses made of bamboo and jute sticks. At 55 years old, his family have lived in a Dhoholakhagrabari chitmahal for generations. Chewing on the twig of a certain tree that locals here use as an alternative to toothpaste, he explains, “All kinds of problems exist here. The government doesn’t care about us, or our children, and so it’s very difficult for them to even go to school. Honestly, we are Indian, but how can we feel this way when we get no help from them?”

For enclave dwellers on both sides of the Indian-Bangladeshi border, the entitlement to receive even the most basic of rights has eluded them.

Reece Jones, an Associate Professor in Political Geography at the University of Hawai’i Manoa, who has visited many chitmahals on both sides of the border, explains further, “After decades in this situation many people have found ways around it through bribes to officials or through friends who helped them to obtain the documents they needed, such as school enrolment forms for their children. However, the situation was not stable or secure. They were extremely vulnerable to theft and violence because the police had no jurisdiction in the enclaves.”

Rupsana Begum, 7, (pink dress) and Monalisa Akter, 7, (orange dress) are from an enclave but were able to come and study at Sher-e-Bangla Government School because their parents managed to acquire fake documents and were able to pay the school.

In Dhoholakhagrabari enclave students and their teacher sit in a madrassa class. Because enclave children have a difficult time accessing the education system in Bangladesh the locals of this enclave formed an Islamic Foundation funded on donations.

Today, after decades left living in limbo in these randomly placed no-man’s lands, around 47,000 people on the Bangladeshi side and some 14,000 on the Indian side have finally been given the right make a choice: stay where they have lived for generations with official citizenship of the country that will absorb them, or return to their country of origin.

None of the residents living in Bangladeshi enclaves within India asked to return to Bangladesh and as a result they will now all become Indian citizens. However, on the other side of the border in Bangladesh, whilst the vast majority of the Indian enclave dwellers decided to stay and become Bangladeshi citizens, 979 people requested to return to India. For these families, the enclave saga has yet to end.

Of those 979 individuals, a total of 406 come from Debiganj district. In 2011, a team of Indian officials visited every home in every enclave in Bangladesh and produced the first ever detailed census of all those living within the Indian enclaves. This report formed the basis of all subsequent decisions on the status of each person living in the enclaves.

An old lady inside her home, which has no running water or electricity, in Dayuti enclave.

Dhonobala Rani, 70, gets emotional knowing that she has to leave her son (in the blue shirt) behind in Bangladesh, as she takes Indian citizenship.

Several months after my visit to document the enclaves during the final days of their existence, those who had chosen to leave for India finally crossed the border, leaving their homes in Bangladesh forever. In India they were given land and began the process of integrating into Indian society. Those who chose to stay behind in Bangladesh also started to receive such basic rights as eligibility to vote and access to health care.

Let us hope that after decades of struggle on these isolated political islands, the lives of these ex-enclaves dwellers can begin to reach some level of normalcy. In the end, after so many years of uncertainty, the world’s strangest border region has now become a thing of the past.

A lady from Ponchoki Bhajini village, in the enclave of Dhoholakhagrabari. She has chosen to leave for India, to start a new life as an Indian citizen.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON MAPTIA.

LUKE DUGGLEBY

Luke Duggleby is a British freelance documentary and travel photographer living in Bangkok.

Is Voluntourism Worthwhile?

Is it worth it to volunteer where there isn’t a sustainable social, political, or environmental impact? I think of those stories of Habitat for Humanity where volunteers think they build a house during the day only to have their crappy work torn down and redone later.

Sincerely,

Wants To Fix The World

Thank you, so much, WTFTW, for giving my first one-word answer to a question of the week:

Nope.

Okay, now to go into a bit more detail: The voluntourism impulse is an awesome one. It means that people don’t just want to take from the places they visit, but to give back as well. It’s akin to helping with the dishes when you’ve eaten dinner at a friend’s house. It’s all that’s right about humankind.

Which is why it’s really depressing that it’s usually a waste of time.

The story I believe you’re referring to is from this excellent article by Pippa Biddle, which is worth giving a read. She talks about a voluntourism trip she took in high school to Tanzania, which cost $3000 a pop:

“Our mission while at the orphanage was to build a library. Turns out that we, a group of highly educated private boarding school students were so bad at the most basic construction work that each night the men had to take down the structurally unsound bricks we had laid and rebuild the structure so that, when we woke up in the morning, we would be unaware of our failure. It is likely that this was a daily ritual. Us mixing cement and laying bricks for 6+ hours, them undoing our work after the sun set, re-laying the bricks, and then acting as if nothing had happened so that the cycle could continue.”

What Biddle concludes is that the problem wasn’t that a library wasn’t needed, it was that she simply wasn’t the one to do it. This is the case with many voluntourism trips: they exist more to give the volunteers the endorphin rush humans get when doing something nice for someone else than they do to actually help. The presence of unskilled volunteers may, in some cases, actually be more of a hindrance than a help.

But sometimes voluntourism is more insidious. The popularity of supporting Cambodian orphanages among western tourists has actually fueled a market for orphans. There are the reports of voluntourists actually taking jobs from better-qualified locals. And for many locals, voluntourism looks more like an expiation of colonial guilt than a good-hearted act of service. In his book Travel as a Political Act (1), travel industry titan Rick Steves points out the name that Salvadorans have for Americans who come to visit and express solidarity, only to return home a few days later feeling self-satisfied: “round-trip revolutionaries.”

Just this week, Prisca Dorcas Mojica Rodriguez, founder of Latina Rebels, made an extremely strong case against voluntourism. Rodriguez was born in poverty in Nicaragua, and vividly remembers the many visiting westerners. She remembers them as good people, but:

"They really wanted us to like them, because they loved us — indiscriminately. It was the sort of love where they did not get our mailing addresses or phone numbers, because it was not about becoming lifelong friends. They loved being around me, it was something about my poverty, brownness, and how they felt like they were saving me. They loved that feeling."

She continues:

"I do not have fond memories of the Beckys and Chads who came to my country and took pictures with me so that they could hang the photos in their dorm rooms and go on with their lives.

Those same Beckys did not stand up against Trump’s xenophobic agenda. The Chads stayed silent during that Cinco de Mayo party that their roommates hosted, perpetuating problematic stereotypes about ALL Latinxs. The Beckys know that NAFTA and CAFTA rulings keep kids like me in poverty, but still shop at stores known for using slave labor and sweatshops.

Those Chads and Beckys have never done anything for me."

As a white person from America, this can sound harsh (2). But it’s worth noting that, especially in Central and South American countries, our country has played a pretty significant role in supporting horrible, genocidal dictatorships in the name of protecting “American business interests.” These dictatorships have frequently taken the place of legitimate left-leaning democracies.

It doesn’t matter if you agree with this assessment of the history of US colonialism in the western hemisphere or not: it’s a fairly widely-held perception in the rest of the Americas (and in parts of the Middle East as well). And in that view of the world, an American paying thousands of dollars to come down for a weekend so he can build a library, feel good about himself, and then return to his affluence, seems like an inadequate form of repentance.

So… should you participate in voluntourism at all?

My suggestion is a gentle no, with a set of clarifications:

1. If you have a set of skills that could be effectively utilized in your destination, absolutely go. Have a medical degree? Join Doctors Without Borders and go do some good. Can you do some consulting work with local NGOs, or provide training that may be desperately needed? Please, go.

2. “Voluntourism” and “volunteering” are not the same thing. If you’re really committing to a project — and not just rolling a pre-packaged project into a vacation — then what I’m saying doesn’t apply. Looking at you, JETs, TEFLs, and Peace Corpsers.

Personally, I think the better thing to do when going abroad is to simply listen to the stories, the history, and the culture of the people that you’re visiting. You should not assume to have answers to a society’s problems after a weekend visit. You don’t. Instead, listen, read, and learn. If you want to help as efficiently and effectively as possible, donate money to people who are already in place to help, and then work on making your society a better place. A more humane America would help make a more humane world.

Still want to try voluntourism?

If you do want to participate in voluntourism, my Matador colleague Richard Stupart put together an excellent guide to finding the most ethical voluntourism projects possible (and, I should note, there are good projects. It’s not all cynicism and neocolonialism). Feel free to add other good ethical voluntourism resources in the comments.

Footnotes

1. Review: meh.

2. It may also paint white voluntourists with too broad a brush — I have no doubt that some Chads and Beckys have spoken out against Trump, NAFTA, and CAFTA, but that’s kind of beside the point — the statement is, as the philosopher Ken Wilber says, “true but partial,” and the truth deserves as much attention as the nuance it misses.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON DON'T BE A DICK TRAVEL.

MATT HERSHBERGER

Matt Hershberger is a writer and blogger who focuses on travel, culture, politics, and global citizenship. His hobbies include scotch consumption, profanity, and human rights activism. He lives in New Jersey with his wife and his Kindle. You can check out his work at the Matador Network, or over at his website.

Featured image by David Sorich.

How do I balance being a feminist with respecting other cultures?

Q: When visiting a country that has a culture that represses women, how far do you go in respecting their culture when visiting? Covering my head and shoulders seems okay. But I have a friend whose husband called out a waiter in India for asking him what she wanted to order when she was perfectly capable of answering for herself. That seems awesome to me but may have been offensive to them. Where’s the line?

Sincerely,

Yes Always to Solidarity with Kickass Women in Eastern & Extremist Nations

That’s a really great question, YASKWEEN. I have opinions, but I am also a dude, and as such, am at risk of mansplaining. So it seems worthwhile to ask a few women who either travel or live in more patriarchal cultures what they think before offering up my own dudepinion.

On cultures that repress women:

When we think of the most oppressive society towards women, we probably think of a country like Saudi Arabia. Sydney Meredith, the travel blogger behind Passports & Prose, currently lives in Saudi Arabia told me she doesn’t love equating “repressing women” with “covering your head and shoulders,” as many Muslim women consider it a personal religious choice to wear the hijab, and not something that’s imposed upon them by men. In regards to wearing it as a traveler, she says:

“I remember visiting historic churches in Spain and France during a trip in high school and the women were asked to cover their shoulders. Do I consider Spain and France ‘repressive?’ No. I was just respecting someone’s wishes.”

She also warns against developing a sense of superiority:

“I mean, aren’t women repressed everywhere? …The US is among only 2 other countries in the world who do not pay pregnant women who take time off from work. We were only allowed to vote just a 100 years ago.”

On "calling people out":

Traveler Sarah Lewis says it usually comes down to reading the situation, and points out there may be alternatives to “calling out” someone that are more effective.

“I feel like in that one specific situation, I would try not to be rude about it, especially at first, because the waiter was just doing what he considers to be polite in his particular culture in his line of work. As a server in the US, I’ve seen men order for women, so for some people that type of thing is still traditional, even in less conservative countries. If he addressed a man I was with rather than myself, I would probably just answer the questions and not necessarily “correct” him per se. (Similar to how in Japan, the server always talks to the Asian-looking person. You correct them not by calling them out, but by just responding in Japanese, and eventually they realize they can talk to you.)”

What’s important, then, is trying to gauge intent. She adds:

“However, if he continued or was being obviously rude to me, that would be another thing entirely, and I think that’s where the ‘line’ sort of starts. If a person is doing something that, even in his culture, would be rude (such as catcalling or harassment), that would not be tolerated.”

On balancing idealism with safety and comfort:

My friend Nandika Kumari is an Indian human rights activist, and she says this regarding the clothes issue:

“The class divide in India often means that urban girls/women from the upper classes will usually dress like any other American twenty year old. However, this is a very small number of people. Most women in India will dress as per their cultural traditions (which are often conservative)… The one rule I’ve always followed is to be 100% comfortable with myself. This also means that in a place where I am likely to get stares if I wear shorts, I will make the functional decision to wear something more conservative so I don’t have to get into arguments with creepy men every 10 steps.”

In regards to the what visitors should do, she adds:

“If someone is just on holiday it probably makes sense to dress close to the way most women in the area are dressed simply to reduce chances of harassment (I know how that sounds). A dress code is only likely to be enforced in religious places. Everywhere else, you are free to dress the way you like. If a woman feels comfortable wearing a dress in an Indian market, then please go ahead and do it. The culture of trying to control women’s behaviour doesn’t need encouragement. Seeing a western woman in different clothing may actually do some good.”

She also noted, “This is India, where you won’t get a death threat for pushing cultural boundaries.” This doesn’t hold true for every country, however, and there are other places where pushing the envelope may be a much more dangerous thing to do. Sarah Lewis adds:

“If something isn’t exactly rude in their culture, but I feel uncomfortable with it, I would probably say something, although again, depending on my level of comfort, I would probably in varying degrees attempt to be sensitive to the culture and not aim to immediately embarrass the person (unless I was really in danger or in a bad situation).”

And, of course, some mansplaining.

Okay, so this isn’t technically mansplaining: I don’t really know what it’s like to travel as a woman, and I won’t pretend to. But I have come across similar situations where something happens in a culture I’m visiting that clashes with my own personal values. A quick story:

When I was working a journalism internship at an English-languge newspaper in China, I really wanted our editors to cover issues like human rights. My bosses had to worry about government censors, so they weren’t really on board with taking editorial advice from an uppity 22-year-old foreigner. I pushed them on it, and all it did was alienate me from my bosses, to the point where I wasn’t being given any work. Towards the end of the internship, I was grabbing drinks with a British journalist who’d worked in China for years. I bitched to him about the Chinese journalists, calling them cowards.

“That’s not been my experience of Chinese journalists,” he said. “I’ve found them to be quite brave.”

I asked how. He said, “You’ve been here what, two months? You need to get to know the system better before you can attack it. These journalists are quite subversive, but they have to be more subtle in their attacks than a British or American could be. They don’t seek to topple anything, just to chip away. Keep in mind very few western journalists are actually risking their necks when they go to work every day.”

He went on to tell me how Chinese journalists would frequently undermine government-mandated stories through the subtle use of puns. For example, when the government wanted to show off their expensive new language-teaching program (which was incredible ineffective), the paper’s editors titled the piece, “GOVERNMENT CREATES ARMY OF CUNNING LINGUISTS.” This effective pun-usage has become so pervasive among Chinese dissidents that censors in China have actually banned the use of puns and idioms.

The lesson of that internship for me was that while the causes I was fighting for were just the world over, the tools for fighting for them changed from place to place depending on the context. It’s easy to fall prey to the whole “when you have a hammer, every problem looks like a nail” trap, and for a lot of Westerners, becoming confrontational over small or large injustices is our hammer.

Your impulse to resist misogyny is always a good one, YASKWEEN, but you may simply not have the localized knowledge to resist it effectively. Which is fine. It creates an opportunity to learn and listen. The best thing you can do if you want to support feminists in the area you’re visiting is to ask them how you can best support them. Some may say money. Some may say political support from your government. Some may say “call out the waiter when he ignores you to talk to your husband.” Some may say, “definitely don’t call out the waiter.” The response will change based on the place you’re in and even on whom you’re talking to.

That said, respect cuts both ways. If you are trying to treat another culture with respect, you’re allowed to insist they treat you with respect as well.

Writer’s note: could we all take a second to appreciate how far I came in a single week with my anonymous questioner acronyms? Last week, I dubbed my questioner “TUTBFTS.” This week, I pulled off motherfucking YASKWEEN. At this exponential rate of improvement, I’ll be a billionaire in a goddamn MONTH.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON DON'T BE A DICK TRAVEL.

MATT HERSHBERGER

Matt Hershberger is a writer and blogger who focuses on travel, culture, politics, and global citizenship. His hobbies include scotch consumption, profanity, and human rights activism. He lives in New Jersey with his wife and his Kindle. You can check out his work at the Matador Network, or over at his website.

To do good, you actually have to do something.

VIDEO: Age Demands Action

An estimated 100 million older people are living on less than $1 a day. Older people are among the poorest and most marginalized in many countries. Older people, especially older women, play key roles as caretakers in support of people with HIV/AIDS and orphaned grandchildren. The nonprofit HelpAge is a network of organizations promoting the right of all older people to lead dignified, healthy and secure lives.

VIDEO: Investing in Abuse in India

The Korea-based POSCO Corporation is pursuing a project in Odisha, India, that is resulting in the violation of human rights. If the project proceeds as planned, some 22,000 people risk being forcibly evicted from their lands and dispossessed from their means of livelihood. POSCO's investors have responsibilities to ensure that the company respects human rights, and to ensure that abuses to not take place in their name.