In September 2020, India passed new agriculture laws that make it much more difficult for farmers to sell their produce at assured rates, as they allow for big corporations to bypass state-controlled markets and buy crops at much lower prices. Since then, various labor unions, political parties, and retail groups have banded together in a standoff against the government to protest this legislation. Strikes are happening in over 20,000 locations across the country; November 26 and 27 of 2020 had a record 250 million people take to the streets in protest, and the marching has not stopped. While farmers continue to hold out in the hope of agriculture legislation reform, it is difficult to get the most current information from the country due to massive communication disruptions. This video details the situation in December 2020, providing an intimate look into the lives, aspirations, and fears of the farmers most affected by the new laws.

Children in a Nepalese village which has committed to ending child labor, a prominent form of modern slavery. The Advocacy Project. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Modern Slavery Remains an Issue to Address in the 21st Century

More than 40 million people are victims of modern slavery today, roughly 1 in every 200 hundred people alive today. From sex trafficking to forced labor slavery abounds. Some classify the forced labor in the US for-profit prison system as slavery.

Read MoreCutting Ties: Saudi Arabia Announces Reforms for Migrant Workers

Saudi Arabia has begun lifting up its struggling migrant workers with its most recent initiative. However, what this decision truly means in terms of effective change remains uncertain.

Saudi women. Mohd Azli Abdul Malek.CC By-NC-SA 2.0.

Saudi Arabia recently kick-started the “Labor Relation Initiative” that will eliminate policies tightly binding migrant workers to their sponsors. It is expected that the changes will begin in March 2021, potentially impacting up to one-third of the nation’s population. This initiative may be the beginning of the end of the notorious “kafala” system that has been under international scrutiny since its conception in the 1950s.

The kafala sponsorship system, which is currently practiced in most Persian Gulf states, began about 70 years ago to create a beneficial flow in the migrant labor force. Workers are assigned a sponsor, or “kafeel,” for their decided contract period. The sponsor may be a single person or a company. The sponsor has complete control over the worker’s ability to change jobs or enter and exit the country; written permission must be granted for any changes. Thus, the worker must report all related activity to the sponsor, and failure to do so will result in criminal punishment. The sponsor must then report all activity to the immigration authorities, and fund the worker’s entry and exit.

Essentially, the kafeel is the migrant’s legal tie to the country, leaving the worker no choice but to acquiesce. The kafala system has allowed kafeels to exercise excessive control over their workers, such as taking their travel documents; this is illegal, though, in some of the countries that practice the system. The kafala system has faced much criticism with claims that it is a gateway to modern slavery; there have been many reports of forced work and sexual abuse. However, it appears that the intense exploitation of workers over the years may potentially begin to close with Saudi Arabia’s new Labor Relation Initiative.

The initiative now allows workers to move their sponsorship to other jobs and to cross the border without permission of their kafeel. The policy is only one aspect of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s “Vision 2030,” in which he aims to increase international economic activity. Many are hopeful that this initiative will bring about substantial change for not only the current 10 million impacted workers, but also future generations who would benefit from the complete abolishment of the kafala system.

Others are wary of holding out hope, stating that ties to a sponsor would need to be completely cut in order for change to be sustained. At the moment, this limited reform has not clarified whether all migrant workers are shielded, nor whether sponsors can still report their workers for running away. Concerns over this unanswered portion of the policy bring much fear; a worker whose travel documents have been invalidated by their sponsor faces immediate deportation.

Maybe this initiative will end the process for good, or perhaps it is merely a camouflaged political scheme. Regardless, much hope remains that the injustices of the kafala system will be reduced.

Ella Nguyen

is an undergraduate student at Vassar College pursuing a degree in Hispanic Studies. She wants to assist in the field of immigration law and hopes to utilize Spanish in her future projects. In her free time she enjoys cooking, writing poetry, and learning about cosmetics.

OPINION: Technology Brings Light to Social Issues—But Can It Implement Lasting Change?

The Black Lives Matter movement in the United States sparked global protests and conversations about the treatment of typically “othered” groups. Despite pressure on social media, education and effective policy reform are still needed to achieve justice for all.

A Black Lives Matter protest sign in London. Ehimetalor Akhere Unuabona. Unsplash.

Following the deaths of Black Americans like George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor, Black Lives Matter surged into the spotlight with renewed vigor. Nationwide protests against police brutality and systemic racism revived conversations about the importance of diversity, equity and inclusion in public spaces. To avoid the consequences of “cancel culture”—the boycott of businesses that fail to embrace social change—many organizations reaffirmed their commitment to racial justice.

On its Twitter account, Netflix emphasized “speaking up” and standing with Black Lives Matter. The ice cream chain Ben and Jerry’s posted “We Must Dismantle White Supremacy” on its website. Some brands even reinvented themselves. Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben’s came under fire for reinforcing backwards racial stereotypes of Black individuals. Their respective parent companies, Quaker Oats and Mars Inc., acknowledged the problematic history of these marketing depictions and committed to changing them.

While many have lauded these actions, others remain skeptical. “Woke washing,” as defined by diversity and inclusion expert Marlette Jackson, is when companies make “public commitments to equality” but fail to create the infrastructure that actually supports Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) staff. For example, Bon Appetit, a monthly American magazine dedicated to global cuisines and recipes, was outed for its empty promises of change. Priya Krishna, a former Test Kitchen star, revealed on Twitter that she was not fairly compensated for her work. She added that staff of color were “tokenized” and framed as “monolithic experts for their communities.” Krishna has since left Bon Appetit.

A billboard for the skin whitening company Fair & Lovely in Bangladesh. Adam Jones. CC BY-SA 2.0

Despite instances of smoke screen marketing, Black Lives Matter has sparked questions of colorism and colonial legacies in countries like India.

In India, lighter skin is considered more desirable. This age-old belief has created a lucrative market for skin whitening products. Not only does the existence of this industry foster a culture of body insecurities, but the products themselves also contain dangerously high levels of mercury and hydroquinone. Since the rise of Black Lives Matter protests in June, many Indian celebrities like Priyanka Chopra have condemned racial injustice in the United States. However, Chopra herself filmed an ad with Fair & Lovely, one such skin lightening product.

According to activist Kavitha Emmanuel, many Indians are “blind to colorism, caste discrimination and violence against religious minorities at home.” Muslims have been lynched in increasing numbers since the ascension of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his party’s Hindu nationalist government. However, many feel that Indians have been more critical of American injustices than the ones happening in their own country. Ultimately, the question remains: are conversations alone enough to achieve lasting peace?

Despite posthumously gracing the cover of Vanity Fair, despite hashtag trends, and despite over 11 million petition signatures as of Oct. 2, Breonna Taylor did not find justice. While the instant and global nature of the internet cultivated efforts to educate and reform, these gestures will not be enough. Unless individuals reexamine the internalized racism and national narratives that so often rule their reactions, ostracized populations will find no reprieve. Until governments step in with effective laws and limitations—ones free of loopholes—Black and marginalized individuals across the globe will continually be devalued and delegitimized.

Rhiannon Koh

earned her B.A. in Urban Studies & Planning from UC San Diego. Her honors thesis was a speculative fiction piece exploring the aspects of surveillance technology, climate change, and the future of urbanized humanity. She is committed to expanding the stories we tell.

Myanmar Government Blocks Website Exposing Military Corruption

The website for Justice for Myanmar, which is dedicated to exposing military corruption, was blocked by the country’s government for spreading fake news. Over 200 websites have been blocked in the past year.

Screenshot of the Justice for Myanmar homepage.

On Aug. 27, all mobile operators and service providers in Myanmar received a directive from the government to block the Justice for Myanmar website for purportedly spreading fake news. Justice for Myanmar was launched on April 28 by an anonymous group of activists aiming to expose military corruption and advocate for federal democracy and peace. Campaigning for Myanmar’s Nov. 8 general elections began a week after the shutdown, raising concerns that the government was attempting to silence scrutiny and criticism of the elections.

In May, Justice for Myanmar exposed that two top government officials were also directors of Myanmar Economic Holdings Company Limited, a military-owned company, leading to both officials’ resignations from its board. More recently, Justice for Myanmar revealed that a construction company under contract for the government has ties to Lt. Gen. Soe Htut. The site also published allegations that a medical company offering Food and Drug Administration approvals is owned by the family of Sr. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing.

The military controlled Myanmar for decades, until it was replaced by a civilian government in 2011. The current government is headed by Aung San Suu Kyi of the National League for Democracy (NLD), who serves as State Counsellor. She led the NLD to victory in 2015 during Myanmar’s first openly contested election in 25 years. Despite having a democratic ruler, Myanmar is not free from military rule. A 2008 constitutional provision still guarantees the military seats in parliament. One-quarter of parliamentary seats are held by the military, which also controls the country’s defense, border affairs and home affairs ministries.

Aung San Suu Kyi, once regarded as a prime example of a democratic leader, has been the target of international criticism in recent years for her handling of the Rohingya crisis and her persecution of media and activist groups.

In the past year, Aung San Suu Kyi’s government has blocked over 200 websites for allegedly spreading fake news, using Section 77 of the Telecommunications Law. The section allows action to stop the spread of misinformation. Myanmar’s government received criticism earlier this year for limiting press freedom and the flow of information during the pandemic by blocking news sites. The government also imposed an internet blackout in nine townships in the Rakhine and Chin states and in April 2020 ordered a mass blocking of the websites of ethnic media organizations. These actions, as well as the shutdown of the Justice for Myanmar website just a week before campaigning for the general elections began, have been causes for concern from the media, community organizations and rights groups.

Yadanar Maung, a Justice for Myanmar spokesperson, said in a recent press release that the group condemns “the Myanmar government’s attack on our right to freedom of expression and the people of Myanmar's right to information.” Telenor Myanmar, one of the service providers that received the directive to block the Justice for Myanmar site, has opened communication with the government to protest the blocking. A statement on Telenor Myanmar’s website urges the government “to increase transparency for the public” and asserts that the government’s directive does not respect the rights to freedom of expression or access to information.

Many groups and individuals, including James Rodehaver of the U.N. Human Rights Office, have called for reform of the Telecommunications Law.

Rachel Lynch

is a student at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY currently taking a semester off. She plans to study Writing and Child Development. Rachel loves to travel and is inspired by the places she’s been and everywhere she wants to go. She hopes to educate people on social justice issues and the history and culture of travel destinations through her writing.

Fight for Civil Liberties Doesn't Stop for a Pandemic in Chile

Despite unrest in Chile, feminist group Las Tesis continues to advocate for justice against police brutality and sexual violence toward women in Latin America.

Translation: “Systemic violence is the worst crime.” John Englart. CC BY-SA 2.0

Last year, Chilean feminist group Las Tesis released “Un Violador en Tu Camino” (“A Rapist in Your Path”), a song that became an anthem against sexual violence worldwide. The piece, which calls out the judicial system and the struggle of women across Latin America, has been performed all around the world in the form of flash mobs. Many who participate wear black blindfolds and green scarves to advocate for legal abortion practices as well.

The song first was created in light of the social inequality protests occurring in Chile in November 2019. The lyrics call out the unfair treatment of the Chilean government toward women. It says that a narrative is being written where women are to blame for sexual violence. Yet, the song places blame on the patriarchy, police and government systems for being blind to this ongoing violence.

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Chile is considered one of the world’s most unequal countries and is susceptible to climate change. Chile is also considered to have one of the highest costs of living across South America. While the rich prosper from their investments in terms of development, the poor communities and Indigenous people suffer at the hands of urbanization.

Feminist sign in Chile which translates to “the feminist struggle is also against neoliberalism.” John Englart. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Many Chileans consider themselves “at war against a powerful enemy.” Rather than succumbing to the protesters’ demands, President Pinera declared a state of emergency that involved the deployment of the military to control crowds and the institution of a curfew. These measures have caused a sharp decline in protests like Las Tesis’.

International attention has focused on the treatment of protesters, with allegations of human rights violations. For instance, there have been claims that protesters may have been tortured, resulting in at least 19 deaths and 20 people being reported missing. Additionally, there has been a 15% increase in sexual violence reports since last year.

However, on June 12, the police filed a lawsuit against Las Tesis. In the lawsuit, police claim that the feminist group encourages violence against officers of Chile’s national police force, Carabineros de Chile. Charges came after the release of “Manifesto Against Police Violence,” a video produced alongside Russia’s Pussy Riot where protesters stood outside of a police station and demanded to “fire the police.” Chilean police took the video as threats against officers, but no papers have been officially served yet to the feminist group.

Daffne Valdes, one of the founders of Las Tesis, said in an interview with Al-Jazeera that “this is an attack on freedom of expression,” calling it a form of censorship. Even though in both the song and video by Las Tesis the police are called out as “rapists,” group members say they are simply referring to the corruption seen throughout Chile’s police system.

Eva Ashbaugh

is a Political Science and Gender, Sexuality, and Women's Studies double major at the University of Pittsburgh. As a political science major concentrating on International Relations, she is passionate about human rights, foreign policy, and fighting for equality. She hopes to one day travel and help educate people to make the world a better place.

Colombian soldiers. Alejandro Turola. Pixabay.

Outrage Mounts as Colombian Soldiers Admit to Rape of an Indigenous Girl

On June 25, seven soldiers of the Colombian army confessed to raping a 13-year-old Indigenous girl from the Embera tribe. She was discovered at a nearby school after having gone missing from her home in the department of Risaralda on June 21. Upon seeing that the young girl could barely walk, she was sent to a hospital and then forensic services along with receiving assistance from the Organization of Indigenous Nations of Colombia (ONIC). Luis Fernando Arias, senior adviser for ONIC, told CNN that the girl “was kidnapped and raped for a period of 17 hours.” The Embera community requested that the soldiers be tried under their own laws along with ONIC “demanding that they be tried under Indigenous law, arguing that it's their jurisdiction since the alleged crime was against an Indigenous person, on Indigenous land.”

Since the alleged rape, the seven men accused were fired along with three of their superiors. The country’s attorney general, Francisco Barbosa, stated that if found guilty the men could face 16 to 30 years in prison, but Colombian President Ivan Duque urged a life sentence for the accused soldiers. He stated that, “If we have to inaugurate the life in prison penalty with them, we're going to do it with them. And we are going to use it so that these bandits and scoundrels get a lesson.” Although many are asking for the imprisonment of the soldiers, Gimena Sanchez, Andes director of the think tank Washington Office on Latin America, believes that, “There needs to be education and consciousness raising within the armed forces on how to treat and how to engage with ethnic minorities. Not just with Indigenous but also Afro-Colombians.”

The country’s response was that of fury, albeit bereft of shock due to the long-standing systemic issue of soldiers' abuse and violence against Indigenous women and girls in Colombia. On July 2, after pressure mounted and Indigenous groups held protests against the gender-based violence of Indigenous women, Colombian Army Commander General Eduardo Zapateiro publicly disclosed that 118 soldiers had been investigated due to incidents of sexual violence against minors since 2016, and of those only 45 have been fired. Despite these statistics, Zapateiro stated that, “These abuses are not systemic conduct. Understand that we are 241,000 men, who every day give everything for the Colombian people.” His argument is that this is not a systemic issue but since the reporting of this story, other cases of sexual violence against Indigenous girls have emerged. One case that was not widely reported until now reveals that a 15-year-old girl from the Nukak Maku Indigenous tribe was kidnapped, tortured and raped in the military barracks of troops in the southern Guaviare department.

Colombia is not exempt from the pandemic of sexual violence that affects women all over the globe but following a vote against a peace referendum to end the conflict in Colombia, women are disproportionately enduring violence on a systemic level. Colombia has the 10th highest rate of femicide in the world, according to U.N. data. The Colombian Femicide Foundation documented that “8,532 women and girls reported that they had experienced sexual violence in the first five months of this year. More than 5,800 were under the age of 18.” The outcome of this case may bring hope to those who want to see justice in the form of imprisonment, but the culture that normalized violence toward women remains.

Hanna Ditinsky

is a sophomore at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and is majoring in English and minoring in Economics. She was born and raised in New York City and is passionate about human rights and the future of progressivism.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and U.S. President Donald Trump. IsraelMFA. CC BY-NC 2.0.

A Surge in Condemnations Follows Israel’s Annexation Plans for the West Bank

The prime minister of Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu, is planning to annex parts of the West Bank on July 1 to extend Israeli sovereignty to new areas. This is a controversial and illegal move according to U.N. experts and much of the international community but comes with the support of the Trump administration.

According to 47 experts appointed by the U.N. Human Rights Council, "The annexation of occupied territory is a serious violation of the Charter of the United Nations and the Geneva Conventions, and contrary to the fundamental rule affirmed many times by the United Nations Security Council and General Assembly that the acquisition of territory by war or force is inadmissible. These experts also deemed Israel’s annexation plan “a vision of 21st century apartheid.”"

Palestinians, Palestinian leaders, and leaders of the Arab world have largely condemned this plan. In the first attempt of its kind, the United Arab Emirates’ ambassador to the United States, Yousef Al Otaiba, wrote in an Israeli newspaper to appeal “directly to Israelis in Hebrew to deter Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu from following through on his promise to annex occupied territory as early as next month,” says The New York Times. The article was a refutation of Netanyahu’s assertion that Arab countries gain too much from Israel to continue supporting Palestinians. In addition to those concerns, many former Israeli defense officials argue that the annexation plan could increase violence within the West Bank, where Palestinians are facing an increase in unemployment. “Imposing Israeli sovereignty on territory the Palestinians have counted on for a future state,” Israeli experts say, “could ignite a new uprising on the West Bank. Neighboring Jordan could be destabilized.”

The news of an annexation plan has brought about new pleas from the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement (BDS), created in 2005 by Palestinians to end international support for Israel’s actions in the West Bank . In May 2020, various Palestinian civil rights groups, human rights organizations, and unions “called on governments to adopt ‘effective countermeasures, including sanctions’ to ‘stop Israel’s illegal annexation of the occupied West Bank and grave violations of human rights.’”

The BDS movement saw a huge victory on June 11 when the European Court of Human Rights shut down France’s attempt to criminalize BDS activists in a 2015 case. At the time of the arrests, the activists were said to be inciting discrimination against a group of people for their origins, race or religion. In the end “the European judges ruled that as citizens these activists had the right to express their political opinions, which are in no sense discriminatory against a race or a religion.” Netanyahu’s expeditious plan to annex is likely to bring about more condemnations from the international community and increase support for the BDS movement, but it is unclear whether these actions will actually halt his plan.

Hanna Ditinsky

is a sophomore at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and is majoring in English and minoring in Economics. She was born and raised in New York City and is passionate about human rights and the future of progressivism

Protest in northern Nigeria in March 2020. Abubakar Shehu. CC 2.0

Nigerian Women Protest Over Police Brutality and Abuse of Women

In light of the U.S.’s Black Lives Matter movement, women in Nigeria have begun their own protests online following the abuse and death of three women.

Since April 2020, Nigeria has seen an extreme increase of sexual violence and police brutality. However, attention was gained on the issue after the death of three women. In April, an 18-year-old woman known as “Jennifer” was gang raped by up to five men. Toward the end of May, 22-year-old Vera Uwaila “Uwa” Omozuma was also sexually assaulted and killed. Around the same time, 17-year-old Tina Ezekwe died after police opened fire on her as she sat at a bus station during a curfew established due to COVID-19.

Unfortunately, the main reason why arrests in Uwa and Jennifer’s cases were made in the first place was due to public outcry, especially from family members of the victims. There was a great fear that those at fault may never be held accountable and that families would never get justice for the wrongful deaths of their loved ones. #JusticeForUwa, #JusticeForTina and #JusticeForJennifer have been used in campaigns across Nigeria, all inspired by Black Lives Matter protests over the past week in the U.S. For Jennifer’s family, it also took the release of a video of her family trying to comfort her to trigger national response.

Arrests, not all, have been made for the death and sexual assaults of Uwa and Jennifer. On the other hand, police who were found guilty for killing Tina have been dismissed by the police department of Lagos but still must face internal disciplinary actions upon further investigation. The regional governor of southern Edo, home of Uwa, also pledged to investigate her case to bring all those to justice.

Photo of Vera Uwaila “Uwa” Omozuma. CNN. CC 2.0

However, many across the country are also fearful of the increase of rapes due to many individuals across the region being displaced. Nigeria has a long history of violence between tribes which makes women feel more vulnerable. Those who are supposed to be watching over the refugee camps have been held responsible for raping girls as young as 9. Being displaced has also caused a phenomenon where families are selling their young daughters for marriage in exchange for money.

In 2014, a survey found that one in four Nigerian women experienced sexual violence. 70% of women even experienced multiple incidents of abuse yet only 5% reported the crimes. Many have linked President Muhammadu Buhari to U.S. President Donald Trump due to the lack of national support and resources readily available to survivors. Most women cannot even receive treatment without filing a police report first. Just as with the assaults in refugee camps, it has caused hesitation in women for filing reports

The internet has become the main outlet for these protests unlike what has been seen in the U.S. Protesting on the street is highly discouraged as protesters could be punished for their actions. Thus, having access to the internet has been able to highlight the injustices of the police in Nigeria. Currently, the #WeAreTired campaign is aimed at not only raising awareness of violence against women in Nigeria, but the overall dissatisifcation with the government in its lack of action.

Just as in the U.S., this has been an ongoing struggle for many Nigerians that has lasted for generations. Since 2015, there has been demand to pass the Violence Against Persons Prohibition Act nationwide which would better define rape in court cases. It is hoped that through these hashtags, people can use their voices effectively and help amplify the message of reform in Nigeria.

Eva Ashbaugh

is a Political Science and Gender, Sexuality, and Women's Studies double major at the University of Pittsburgh. As a political science major concentrating on International Relations, she is passionate about human rights, foreign policy, and fighting for equality. She hopes to one day travel and help educate people to make the world a better place.

Graves at the memorial center Potocari, near Srebrenica. AP Photo/Amel Emric

Bosnia’s 25-year Struggle With Transitional Justice

The Bosnian war started 25 years ago this week.

Although bombs ceased falling in 1995, in many ways the people of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) are as divided as ever. The past two decades have repeatedly shown that divisions exacerbated by the war continue to permeate politics.

In fact, according to a 2013 public opinion poll, just one in six residents of BiH feels that the three ethnic groups that live there – the Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats – have reached reconciliation.

It would be easy to pass this sentiment off as what one former U.S. secretary of state called “ancient tribal, ethnic and religious rivalries.” But I believe it raises profound doubts about the ability of international justice to bring about a more peaceful world.

As I demonstrate in my book, “The Costs of Justice,” transitional justice – the process of dealing with human rights abuses committed by a previous regime – is an inherently political process made even more contentious by taking it out of the country. The fallout is not just a lack of reconciliation, but also the constant threat of violence.

In BiH, more than 30 percent believe a renewal of armed conflict could be right around the corner.

The G word

Ongoing resentment in BiH was highlighted by two recent events.

First was the fall election of a Serbian genocide denier, Mladen Grujicic, as mayor of Srebrenica – a town where more than 8,000 Bosniaks, or Bosnian Muslims, were systematically killed in 1995.

Next came the Bosniak response: a February request for the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to review its 2007 ruling that cleared the neighboring state of Serbia of complicity in genocide during the war.

The war may be long over, but wounds are still oozing.

Lack of reconciliation in BiH comes despite – or perhaps because of – a major international effort to ensure justice in the region. BiH, like other states of the former Yugoslavia, was under the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) at The Hague for more than two decades.

The ICTY’s establishment in 1993 was greeted by human rights advocates as the harbinger of a new era of justice. At the time, transitional justice scholars preached its numerous benefits. These included deterring future rights violations, strengthening rule of law, increasing the legitimacy of a new regime and, perhaps most importantly, encouraging reconciliation within broader society.

There are many ways to address past rights abuses – from issuing apologies and providing victim compensation to holding truth commissions and launching criminal trials. The international community has historically focused on the latter – whether at Nuremberg, Tokyo or The Hague.

Criminal prosecutions are largely symbolic, but they are nonetheless important. They signal the end of impunity, or the ability to escape punishment, and the start of a more just order. The fact that post-conflict countries frequently lack institutions strong or independent enough to pursue criminal prosecutions on their own makes international mechanisms indispensable. Indeed, BiH’s inability to carry out its own criminal trials for a decade and a half points to a real need for international courts.

But the very process of taking criminal prosecutions out of the domestic purview can ultimately be a blow to justice. Most locals, for instance, lose interest in trials that play out in faraway courtrooms, meaning trials fail to bring about the sorts of dialogue that might lead to mutual understanding.

Formidable challenges of international prosecutions, from learning the intricacies of a foreign culture and political regime to collecting evidence essential for a successful prosecution, mean that international trials also take a long time to complete. And, of course, they are expensive. The ICTY cost more than US$1 billion, or between $10 million and $15 million for each person accused. Various countries, including the United States, footed the bill.

And yet, rather than improve relations in the region, the ICTY may have incited tensions. Each of the parties claimed they were unfairly targeted. Serbs were infuriated by their overrepresentation on the court’s docket. Croats couldn’t believe that any of their heroes were facing judgment.

Little surprise then that only 8 percent of those polled in BiH in 2013 felt the ICTY had done a good job facilitating reconciliation.

While international courts did little for reconciliation, they fundamentally sabotaged more organic forms of justice than could otherwise have happened at the local level. In the former Yugoslavia, political leaders who were struggling to balance international pressure for – and domestic opposition to – ICTY cooperation opted for half-baked local initiatives designed to satisfy both. The result was a watered-down truth commissionhere, an apology of questionable sincerity there.

These half-measures ultimately replaced what might have been more earnest mechanisms had they not been established in the context of ongoing international trials. The recent Bosniak appeal to the ICJ, just like the key political victory of a Serb genocide denier, highlights the degree to which justice and historical memory remain politicized in BiH a quarter-century after the war began.

The ICTY’s long shadow

The ICTY and subsequent tribunals demonstrated that international prosecutions can play an important role in ending impunity. But they must carefully balance the need of the international community to ensure accountability with the needs of a local populace to deal with past rights abuses on their own terms.

Limiting international prosecutions to the most serious perpetrators is one way to reach this balance. Few in Serbia shed tears for the arrest of Slobodan Milosevic, a corrupt dictator.

Even then, the recent experience of the International Criminal Court (ICC), established in 2002 as a permanent and global version of the ICTY, demonstrates this can be a tough sell. Numerous African states have accused the ICC of the same bias Yugoslavs attributed to the ICTY. They are threatening to withdraw as a result.

Back in Bosnia, the ICJ last month rejected the Bosniak request on the grounds it did not come from all three members of the country’s tripartite presidency. In other words, the very lack of reconciliation between Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats that prompted the initial appeal now makes that appeal impossible. It is ironic that Bosniaks still feel the need to turn to international justice mechanisms for redress. After all, international justice may bear some blame for the predicament they’re in today.

Brian Grodsky is an Associate Professor of Political Science, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Flip Your Map and Up Your Impact

Part 1 of a 2-part series on Maps

The map of the world.

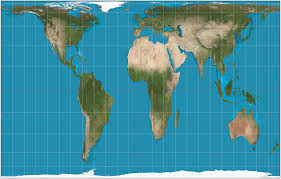

When we look at the most commonly-seen map of the world, we assume that it depicts the earth as it truly is. But this particular projection of the world, like all others in existence, isn’t completely accurate, as it is impossible to avoid distortions when translating three dimensions into two. Known as the Mercator projection, this map was designed for navigation but distorts relative size, artificially enlarging land masses further from the equator. The result is more severe than you might imagine: Africa appears smaller than Greenland, when it is actually fourteen times larger. See this for yourself here.

There are many other, less common projections which you can explore here. Some are equal area projections, such as Gall-Peters, which manage to avoid the relative size distortion of Mercator but are then much less useful for navigation and less accurate with regard to shape. While the Mercator projection has been abandoned by atlases in favor of projections with more balanced distortion profiles, it is still used by popular online navigation tools such as Google Maps given its navigational prowess (unless you happen to be exploring one of the poles, where it is practically useless).

Gall-Peters Projection

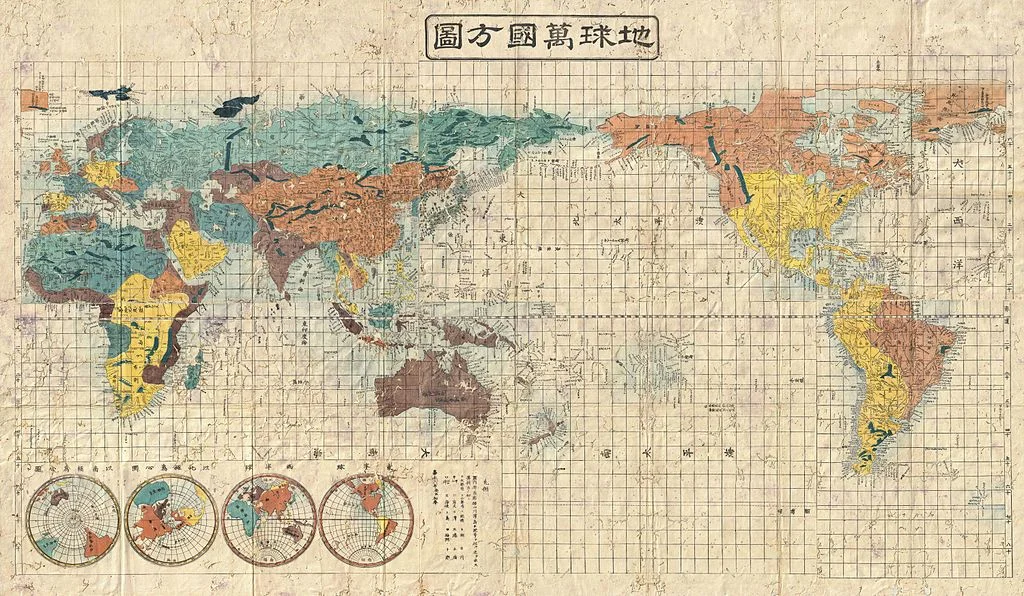

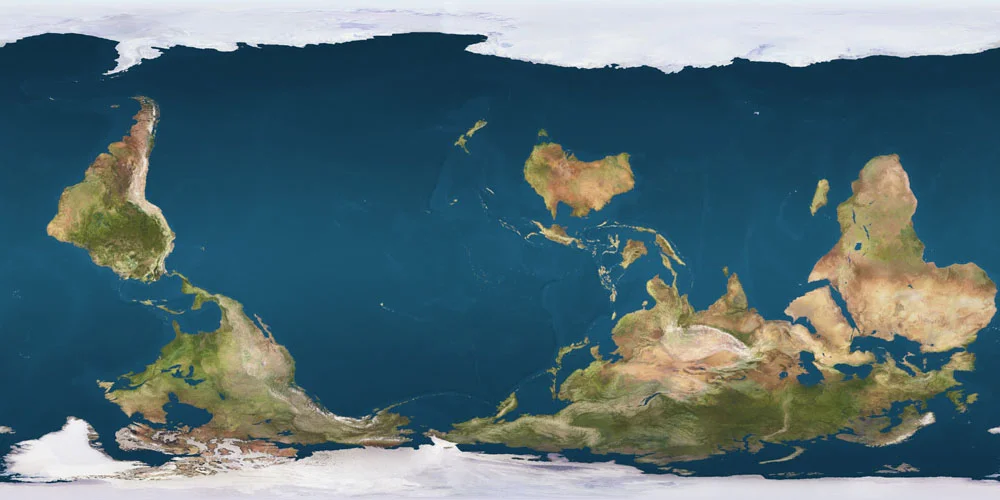

The most commonly-seen map of the world also has a particular orientation and center: north-up and the Atlantic. Yet this framing is neither inevitable nor inherently more correct. Medieval maps were often East-up, Pacific-centered maps pop up in Asia, and a National Geographic feature on the world’s oceans opted to carve up continents instead of bodies of water.

As a result of the complex politics of map-making over time and the inertia of convention, the north-up, Atlantic-centered Mercator projection is the most prevalent, making it not only a navigation tool, but also the image of the world in our mind’s eye. But why does this matter? If all projections are distorted in some way, and orientation, although heavily influenced by historical political jockeying, is ultimately arbitrary, can’t we just continue using it?

There is a big reason why this is not such a great idea: where things are on the map and how big they are in relation to other things affects what we think of them.

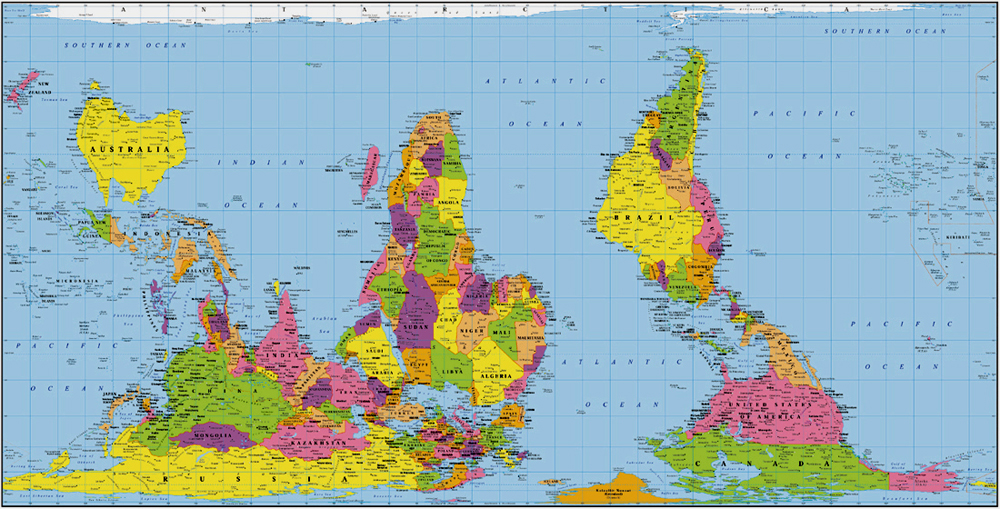

Research has shown that we (English-language users) tend to associate up with goodness and down with badness; think about upper and lower class, movement along the socio-economic ladder, “started from the bottom now we’re here”, the assumed location of heaven and hell, and the connotations of uptown and downtown. It has also shown that we tend to associate up with north and down with south (“up north”, “down south”) despite the fact that up/down is an orientation to gravity while cardinal direction is an orientation to the poles. When we are repeatedly exposed to the north-up world map, it reinforces the association of up with north and down with south, and therefore strengthens the association of north with the positive qualities associated with up, and south with the negative qualities associated with down. The popularity of the north-up map makes us more readily associate positive things with northern places.

We also tend to associate things in the center of an image with importance, and large objects with importance and strength. Overall, this means that we tend to equate things that occupy large, upper (northern), central places on the map with goodness, importance and strength; and things that occupy smaller, lower (southern) and peripheral places with badness, insignificance and weakness. It is therefore not surprising that some Australians, Asian states, geographers, educators, and even people on The West Wing have pushed for south-up, Pacific-centric and non-Mercator maps.

Now you might be thinking, but I know that those things don’t always match up! Rwanda has a higher percentage of female Members of Parliament than any other country on earth even though it’s in the Global South! China is hugely important in the global economy even though it’s on the periphery of the map! Israel is powerful even though its relatively small size is exaggerated by its proximity to the equator!

But these mental links, also called implicit associations, are mostly unconscious, and they show up in many areas of our lives even when we consciously know and believe that they aren’t correct. In other words, stereotypes and generalizations affect our decisions and behaviors even though we know they aren't always true. This insight comes from implicit association tests, which show that we are quicker and more accurate at sorting things into bins when the bins match up with unconscious associations in our brains, even when we report not having these associations. For example, when sorting words or images that are often perceived as fitting into just one of four categories - fat, skinny, good, bad - we tend to be faster and more accurate when we are putting items that we perceive as fat or bad into one box, and items that we perceive as skinny or good into the other box. We are on average slower and more likely to mess up when we instead have to sort into a box for skinny or bad items, and a box for fat or good items. And this happens even when we report that we don’t believe fatness is inherently associated with badness, or skinniness with goodness. See this for yourself by taking multiple versions of this test.

The most probable explanation for this phenomenon is that it's an evolutionary remnant, which in the earlier days of humanity helped to keep us alive by allowing us to quickly distinguish between safe and unsafe through stereotyping. But the modern-day implication is clear: even if we don't explicitly think that northern, central, or large countries are better, stronger and more important, associations between these categories probably lurk in our psyches. Where things are on the map and how big they are in relation to other things affects what we think of them regardless of whether or not we realize it’s happening. We don’t just shape maps, maps shape us.

These mental links may seem harmless, but researchers have suggested that implicit associations in general contribute to everything from childcare expectations for different genders to police brutality against people of color. They affect decisions like whether or not to cross the street when we see someone walking towards us, where to travel, and which deaths from terrorist attacks to change our profile pictures for.

The particular mental links created and reinforced by this map aren’t harmless either, as they correlate with current and historical global patterns. And when these mental links line up with what’s happening in the world, they perpetuate each other. Although it is sometimes quite handy that associations from our dominant map match reality, it is also limiting, as we tend to see characteristics of certain places as natural and normal, and the resulting global power dynamic as inevitable. For instance, this map and the associations it fortifies make it harder for us to imagine a world where the West (a confusing term generally used to refer to Northwestern Europe, the US and Canada) isn’t the most powerful and important group of countries. When we see things as inevitable and can’t fathom a different reality, we are less likely to intervene to change the course of history. We cannot go somewhere that we have not first traveled in our minds, and with maps reinforcing the status quo instead of igniting our imagination of how the world could be, we are more likely to perpetuate global systems of oppression.

The mental links reinforced by repeated exposure to this map don't just prevent us from taking action, they can also lead us to take part in less-than-ideal action. For example, this particular map reinforces the belief that the West is inherently good and that all countries should strive for our way of life. This belief then informs actions in many sectors, from foreign policy to international development, often resulting in detrimental outcomes for people and planet. Individually, we are encouraged to engage in well-intentioned efforts such as teaching English, which, instead of indisputably beneficial, can be seen as an effort to make “them” more like “us”. Beliefs arising from the associations this particular map reinforces don’t just prevent us from changing things, they support harmful things happening right now.

Instead of being held back by exclusive familiarity with only one of an infinite number of possible projections of earth, we can improve our chances of having a genuinely positive impact by changing our maps. We can continue to use Mercator projections for navigational purposes, but we should switch it up for non-navigational purposes. When hunting down the exact location of a current event you’re reading about, scroll over a pole in Google Earth to flip the world upside down. If you’re buying a world map poster to plan your next trip or track where you’ve been, consider a Gall-Peters projection, south-up or Pacific-centered map; all are relatively easily to find online.

Over time, as you expose yourself to different maps, your mental maps will shift, decreasing the power of certain associations and helping you combat your unconscious internal bias. While daily exposure to our culture and language makes it very hard to de-link up from good, and large and center from important and powerful, changing your maps can delink north from goodness, Africa from weakness, and Small Island States from insignificance (they are, after all, a key climate change frontline). Switching between maps will also remind you that the map is not the territory, and that all maps simultaneously obscure and illuminate. We can also expose ourselves to stories and other media that contradict these associations, a tactic which has been shown to reduce bias when measured with implicit association tests. Purposefully and regularly exposing yourself to other perspectives is also a good life practice, especially for people of privilege, and one of the things travel is perfect for.

SARAH LANG

Instigated by studies in Sustainable Development at the University of Edinburgh, Sarah has spent the majority of her adult life between 20+ countries. She is intrigued by the global infrastructure that produces inequality and many interlocking revolutionary solutions to the ills of the world as we know it. As a purposeful nomad on a journey to eradicate oppression in all its forms, she has worked alongside locals from Sweden to Zimbabwe. She is a lover of compassionate critique, aligning impacts with intentions, and flipping (your view of) the world upside down.

VIDEO: Introduction to Women's Status is Cambodia

This video was produced by Promotion of Women's Rights project (2002-2011), predecessor to Access to Justice for Women project. The video comprises an overall introduction to women's status in Cambodia as well as the main actions undertaken by the Ministry of Women's Affairs -with the support from GIZ- in order to tackle gender inequalities and gender-based violence in Cambodia.

What is Social Justice?

Pop culture has many definitions of the word social justice. After years of working with these issues as an org. and seeing our community make an impact in this world. We are raising our hand and asking "What is Social Justice to you?"

The Love Alliance has started this campaign to support individuals and groups in what they are currently doing and to encourage them to get more involved with these issues. This campaign is meant to be a positive and uplifting voice to the conversation about social justice.

So we ask...What is social justice to you?

LEARN MORE AT whatissocialjustice.com

A Video Volunteers Film: The Fight for Justice Against Acid Attacks in India

In this Video Volunteers film, the IndiaUnheard correspondent, Varsha Jawalgekar, exposes the acid attack on Chanchal Paswan, 19, and her sister, 15, while they were asleep on their terrace. The attack was a result of their opposition to previous sexual harassment by the men. In the West, horrific attacks as such would be covered by major news media. However, in India, Video Volunteers is doing immensely important work getting information about this out and accessible.

CONNECT WITH VIDEO VOLUNTEERS

The Poverty Song

Wilbur is a musician, creator of a new genre called Indo-World Fusion. He is a tireless ambassador for cultural intelligence and has a passion for humanitarian and social justice issues. He loves to make the common extraordinary. Here... the Poverty Song, and his message... "stop the shopping spree, end poverty."

CONNECT WITH WILBUR