A decades-old conflict in Central Africa threatens to reignite in full, with worldwide implications.

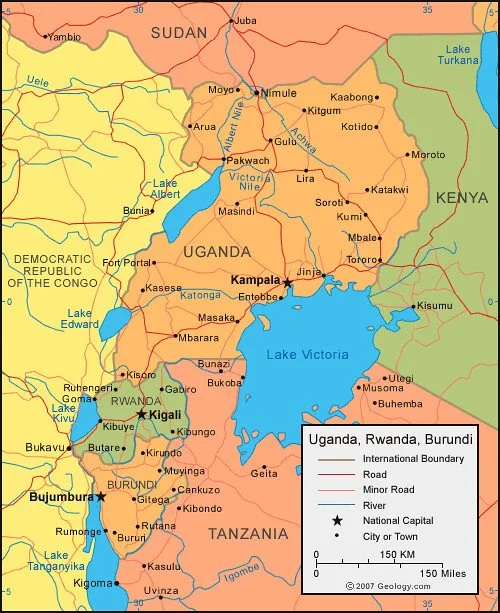

Map of Rwanda and its neighbors. Jerry Zurek. CC BY-NC 2.0

For perhaps the first time, American activists are starting to pay attention to the Congo.

The anti-government M23 militia, a rebel outfit based in Eastern Congo, has recently captured the town of Rubaya, an important coltan mining hub in the Democratic Republic of the Congo's (DRC) North Kivu province. The group seized control on April 30, 2023.

While at first glance this appears to be a civil conflict, the Congolese government losing territory to Congolese rebels, it is more accurately described as an act of aggression by neighboring Rwanda. That is because M23 is widely known as a proxy force under the thumb of Rwanda's President Paul Kagame, an intelligent and efficient statesmen who has rebuilt his country from the ashes of the Rwandan genocide at the cost of tyranny at home and terror abroad.

Rwanda's involvement in the DRC began in the aftermath of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide, a horrific 100-day slaughter in which ethnic Hutu militias murdered about 800,000 Tutsi civilians and political opponents. Millions of Hutus—including many genocidaires, genocide perpetrators—fled into Zairean (Zaire was the name of the DRC at the time) territory to escape retribution from the victorious Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), Kagame's largely Tutsi military and political organization that conquered Rwanda and ended the genocide.

Kagame's army followed the genocidaires deep into the Congo basin, beginning a series of conflicts in the soon renamed Democratic Republic of the Congo that have killed millions since the mid 1990s. The conflict, so complex and cataclysmic that one author has dubbed it "Africa's World War," is too large of a story to cover here in full, but ever since Rwandan-backed forces have held large chunks of DRC territory, attacked Congolese civilians and pilfered its natural resources, according to the the DRC's President Félix Tshisekedi.

In Rwanda itself, Kagame's 30-year reign has been deeply authoritarian, with the bulk of high-ranking officials drawn from his minority Tutsi coethnics and relatively few Hutus, who make up the overwhelming majority of the country's population. In addition to the typical election rigging, political murder and wrongful imprisonment of autocratic leaders, the President's antics have included the kidnapping from abroad of the Hutu man whose heroic saving of more than a thousand Tutsis during the genocide was adapted into the movie "Hotel Rwanda."

The DRC's North Kivu province, where the recent fighting has taken place. Derivative work: User:Profoss - Original work: NordNordWest. CC BY-SA 3.0

Despite his foreign adventurism, not dissimilar to the kind that has made Russia's Vladimir Putin a pariah in much of the world, President Kagame seems to get on well with world leaders and IMF bigwigs. The UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak is holding fast to his plan to deport asylum seekers to Rwanda, paying the Rwandan government $300 million in 2023 to accept undocumented migrants to Britain. The first asylum seeker to leave the UK for Rwanda did so on a voluntary basis in late April, 2024.

Critics allege that Mr. Kagame has slyly used the memory of the Rwandan Genocide avoid Western criticism and sanction for his autocracy and international aggression. While this has been largely effective up to this point, France's President Macron now claims to stand steadfastly behind the Congolese and American patience with Kagame may be running out. DRC President Tshisekedi has personally called out Kagame as the "real aggressor, real criminal" behind M23 and its continuing massacre and displacement of Congolese civilians, and his government has accused Apple and other companies of buying "blood minerals" from the Rwandans.

To hit back against critics, the Rwandan leader has claimed that the incursions into his western neighbor are needed to prevent another genocide against his Tutsi coethnics. This might ring hollow to the members of the more than 200 other ethnic groups in the DRC, the vast majority of whom have nothing to do with the Hutu, Tutsi or Rwanda in general. Kagame-backed militias have themselves been accused of extermination, along with cannibalism and other ghastly crimes, perpetrated against pygmy groups in Eastern Congo. To justify their agony with the 1994 Rwandan Genocide requires a solipsistic focus on Tutsi suffering at the expense of everyone else in the region.

Some activists on TikTok have taken notice of the crisis, although they tend to discuss the events in abstract economic terms that obscure the events and agents involved. Western consumers and companies are certainly implicated in Eastern Congo's agony, but these political-economic models should be built up to from a solid understanding of the events and agents involved, and not lead with.

In an interview with DW, Congolese President Tshisekedi describes recent initiatives as a "final crossroads," a "last chance" for peace between the two countries, hinting at a broader war to drive the Rwandans out for good. Such a war would be devastating for the region, and indirectly touch every consumer of modern technology via the mineral trade. Time may be running out for a solution. It seems that the choice, as it has so often been for the last 30 years, is Kagame's.

To get involved:

To support Congolese women you can donate to Women for Women International, helping women receive vocational training and training to defend their rights.

Save the Children works to deliver humanitarian aid to children in the DRC, including those displaced by war and suffering from diseases like cholera.

Doctors Without Borders is one of the few medical aid organizations to continue operating in North Kivu's Rutshuru area, home to much of the fighting. Donating can help directly support the people most in need of medical treatment.

Dermot Curtain