If you ever find yourself struggling with Athens’ summer heat, cool off in its museums and discover a whirlwind of art and civilization.

Small statues typical of the Cycladic Culture, which flourished between the fourth and second millennia BC. Taken by Dermot Curtin.

A human face represented only by an angular nose bridge and a semi-oval silhouette. A procession of curvilinear stick figures, lavished with somewhat less detail than bizarrely eight-legged horses, inanimate chariots and abstract designs. A general preference for the symbolic over the literal and the real. Much of the art you’ll find in Greece’s National Archaeological Museum (NAM)is highly abstract; parts of the collection, particularly those of the Cycladic Period, have a distinctly postmodern feel to them. Such works, however, are not the product of the 19th and 20th century revolt against Greco-Roman and Renaissance verisimilitude, long a dominant force in European art. They instead predate the Classical period and its values by hundreds or thousands of years.

Almost all visitors to Athens who can take the heat make the long, slow trek up the Acropolis to see the Parthenon. Many of those will then visit the Acropolis Museum, a relatively new museum home to much of the pride of Greece’s classical heritage, including the portion of the Parthenon Frieze that Thomas Bruce didn’t get around to looting (plaster casts of the originals fill in gaps, labeled with an ignominious “BM” for British Museum). Still popular, but less of a universal attraction, I found the National Archaeological Museum to be the more interesting of Athens’s two great museums dedicated to antiquity. The NAM’s more varied collection allows visitors to chart the development of Greek style over several millennia, seeing works that are stunning in themselves and better understanding of one of the most radical changes in aesthetic values before the modern age.

The original segments and fragments are noticeably grayer than the majority plaster copies. Taken by Dermot Curtin.

Greece’s island territories were its most precocious in terms of art and civilization. The Minoan and aforementioned Cycladic cultures left a remarkable heritage, which stand in marked contrast to later Hellenic society and each other. Cycladic art is most famous for its austere minimalism, especially as expressed in statues such as the two in this article’s introductory photograph. The Minoans took a different approach, painting vivid frescoes which have, in part thanks to a volcanic eruption sometime between 1650 and 1550 BC, survived thousands of years in good condition. Human figures in Minoan art are stylized, but are far from the degree of abstraction found in their Cycladic semi-contemporaries. Many Minoan paintings not saved by volcanic ash were unearthed at the Palace of Knossos, where King Minos of Greek myth was said to have fed young Athenians to the dreaded Minotaur every year in the Heroic Age.

Two Minoan frescoes, originally from Santorini and preserved by its great eruption. Taken by Dermot Curtin.

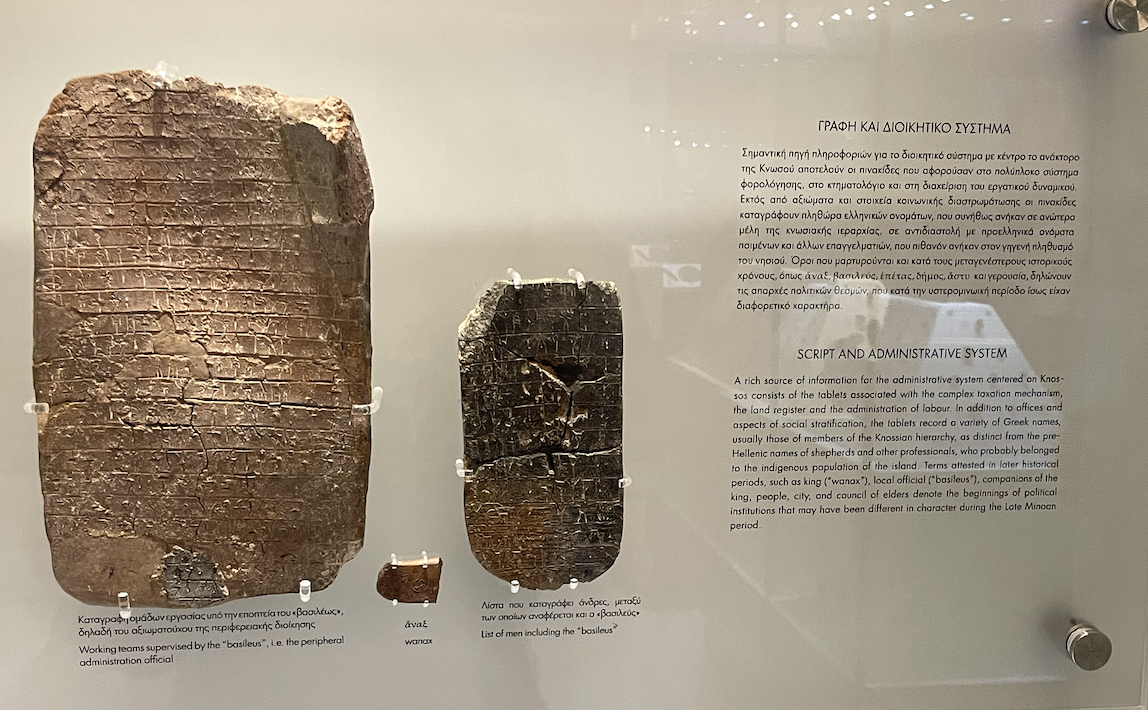

Although the Minoan civilization flourished on what is now Greek soil, in one respect it was not yet a Hellenic society: language. The Minoans developed their own system of writing, known to history as Linear A, around the 19th century BC. It has never been deciphered, but linguists have been sound out its symbols since its direct descendant, known as Linear B, was cracked in the early 1950’s. Linear B tablets represent the earliest recorded form of the Greek language called Mycenaean Greek, and are generally administrative documents that the elite used to keep track of their resources and labor. Mycenaean tablets from Crete are indirect evidence for the rise of Hellenic culture in insular Greece, recording a nobility that used Greek names and lower orders with older, native Minoan names. The Mycenaean culture originated in mainland Greece, and expanded south and east into what are now the Greek islands. The Minoan language has no confirmed relatives or descendants.

Linear B tablet from not long after the Mycenaean conquest/cultural shift in the 1400s BC. Taken by Dermot Curtin.

Mycenaean Civilization was famous long before its archaeological rediscovery in the late 19th century as the setting of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Although Homer composed centuries after the Bronze Age Collapse of circa 1200 BC, he knew many details about the earlier period; the blind poet placed Agamemnon, the the most important leader of the Greeks in the Trojan War, on the throne of Mycenae, which modern archaeology has revealed to be the largest city of the age. Many of the most significant finds from the Hellenic Bronze Age are ornately decorated thin gold sheets, which are part of a broader European artistic trend of the same period. I was immediately reminded of similar (albeit less intricate) artifacts from Bronze Age Ireland. Other works, such as the beautiful inlaid dagger below, have no obvious parallel.

Many gold Mycenaean artifacts from the National Archaeological Museum. Taken by Dermot Curtin.

Disk from a Reel, Irish, c. 800 BC. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. CC0.

Gold Dagger from the National Archaeological Museum. Taken by Dermot Curtin.

The Bronze Age Collapse hit many areas hard, and Greece harder than most. Linear B fell out of use around 1200 BC, leaving the Hellenic world without a script until about 200 years later when the Phoenician abjad was modified for the purpose, with vowels added to make it a viable option for the Greek language. Greece had entered its Dark Age, a radical departure from the centralization, trade and literacy of the Mycenaean and Minoan eras. Despite this, literature flourished; Homer and Hesiod composed their epics, laying the foundation for millennia of inspiration and adaptation.

Two Geometric amphorae from the National Archaeological Museum, from an age (900-700 BC) defined by abstract art. Taken by Dermot Curtin.

As civilization began to recover from the Collapse in the tenth century BC, the Geometric style emerged to fill the void left by Mycenaean art. This style was deliberately abstract, characterized by repeating linear patterns on large amphorae. People, when present at all, appear as small stick figures. Mourners dramatically and uniformly put their hands on their heads, their arms bent at sharp angles that would look unnatural on a more realistic human design; such a pose is necessary to convey distress, as the faces are not given enough detail to show any kind of emotion. The meandros, a repeating pattern that would later be a common fringe for other designs, here takes center stage, while the funerary procession is confined to a narrow box in the upper-center of the amphora. There is little to differentiate one person from another, the exceptions being a child, who is clearly smaller than the adults, and the deceased, who lies on his or her back. Geometric style seems to be the product of a culture that did not value the individual human being as a subject for artistic expression.

Marble statue of a youth, from Archaic Greece c. 590-580 BC; you can see the abstract art of the Geometric give way to stylized human forms. Metropolitan Museum of Art. CC0.

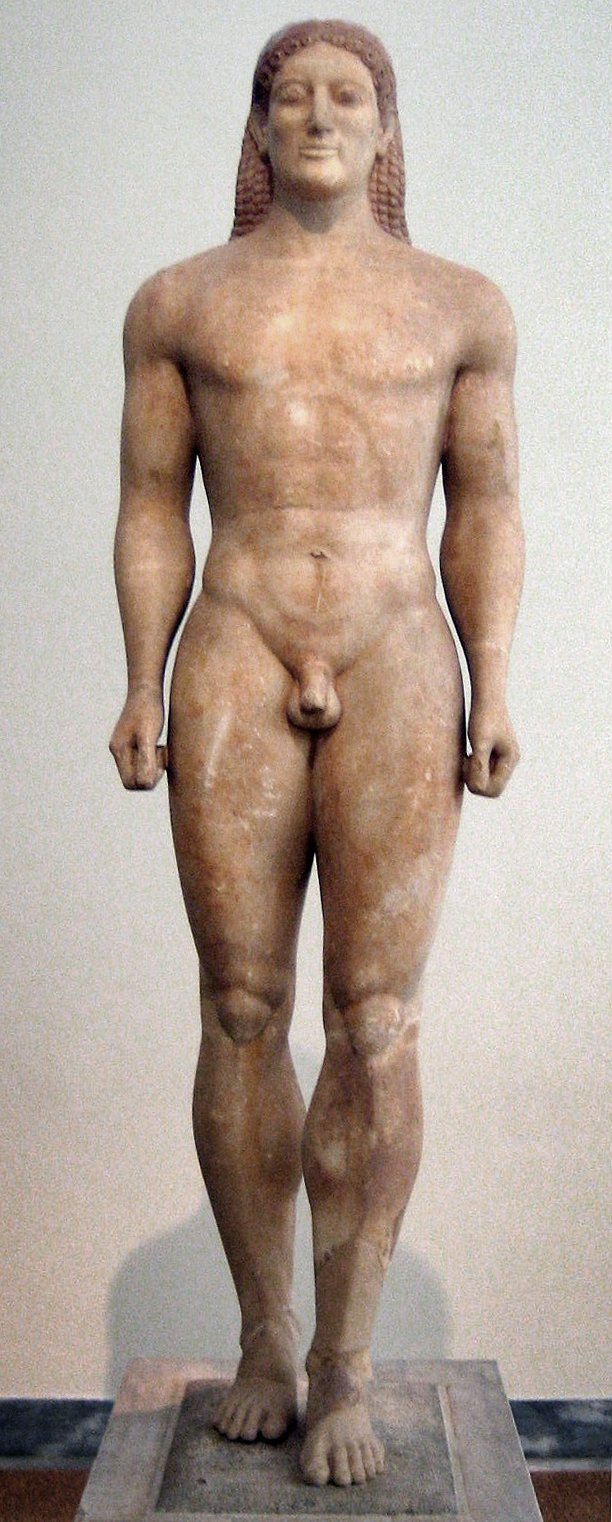

The Kroisos Kouros, c. 530 BC. User:Mountain. CC0.

Greece only fully recovered from the Bronze Age Collapse as it transitioned into its Archaic period around the eighth century BC. In this period, as Greek culture built up to its fifth century zenith, the seeds were planted for many of the institutions and conventions that would flourish in the Classical era (beginning 480 BC with the end of the Persian Wars). The Olympic games were founded, dramas began to be staged in Athens and lawgivers like Solon imposed constitutional reforms that would eventually lead to democracy. The visual arts made a dramatic turn, as abstract designs retreated to the background in favor of a strong emphasis on the human form. The most typical art form of the time is the kouros, a strongly stylized nude statue of a male youth. Although sometimes differing in size and detail, all kouroi adhere to the same basic plan, standing up straight with the left foot out front, braided hair and a serene affect. The figure on the right was made about 50 years later than its counterpart to the left, and although clearly the product of more skilled craftsmanship does not deviate from the essence of the older model.

Statue from the Egyptian Old Kingdom that resembles the Greek Kouros; note the forward left foot. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. CC0.

Although impressive in their own right, such statues are not dissimilar to art produced by Middle Eastern cultures in the Bronze and Iron ages. Initial kouroi designs seem to have been borrowed in part from Egypt during the early part of the Archaic period. In the jubilant aftermath of the Greek victory in the Persian Wars, however, Hellenic artists made an unprecedented turn toward realism that would cement Greece’s place in art history for all time.

Roman copy of Polykleitos’s famous Diadumenos, original circa 420 BC. Taken by Dermot Curtin.

A Greek sailor looks out wistfully on the sea battle where he died, funerary stele. Taken by Dermot Curtin. (melancholy)

Ancient art reached its apogee in the Classical period of the fifth and century BC. This is the era which would come to define Greek civilization, and marks one of high water marks of cultural production the world over. In the visual arts this meant a form of idealized realism, meant to portray natural forms in their best possible state. This involved more than technical skill, as sculptors like Polykleitos incorporated specific mathematical proportions into their work in their drive for perfection. The incredible detail allowed for greater subtlety of design; compare the melancholy of the fallen soldier on the left to the sharp and uniform gestures on the Geometric mourners above. The sculptures look like people you could actually know, except fitter and far better looking.

Geometric amphora. Taken by Dermot Curtin.

Terracotta volute-krater with red figure design, circa 450 BC. Metropolitan Museum of Art. CC0.

The period between 750 and 450 BC saw a revolution in aesthetic values, matched only by the modern rise of modern art in the 19th and 20th centuries. In the Ancient Greek world, however, the shift was in the opposite direction, from the abstract to the concrete. The change in taste was coincided with a dramatic rise in skill, leading to works that still keep many of the world’s art historians and critics occupied. If you ever find yourself in Athens, make sure to visit the National Archaeological Museum to experience the whirlwind for yourself.

Dermot Curtin

Dermot is copy editor and a contributing writer at CATALYST PLANET. He is a recent graduate of William & Mary, majoring in History and Government, and enjoys learning about the world and conveying his experiences through writing.