There are many indexes that aim to rank how green cities are. But what does it actually mean for a city to be green or sustainable?

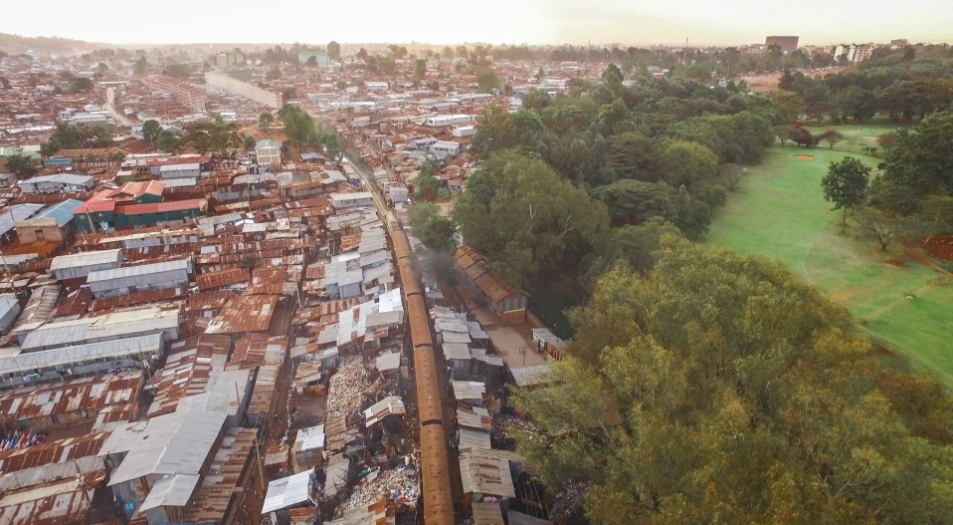

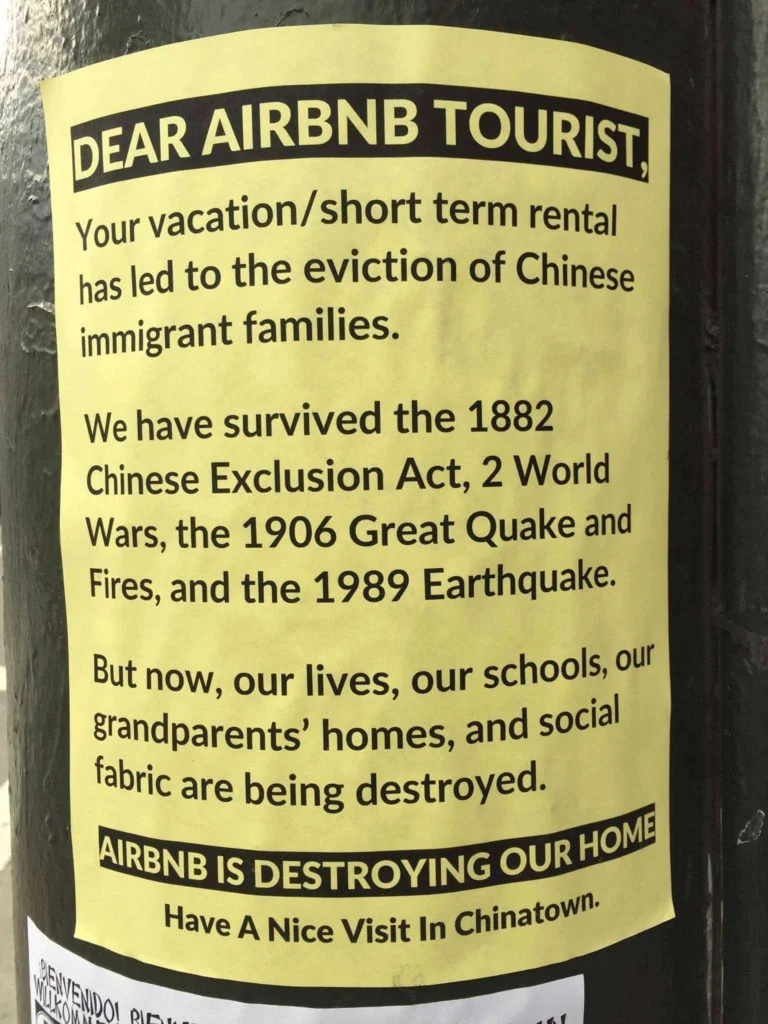

We’ve written about what we call the “parks, cafes and a riverwalk” model of sustainability, which focuses on providing new green spaces, mainly for high-income people. This vision of shiny residential towers and waterfront parks has become a widely-shared conception of what green cities should look like. But it can drive up real estate prices and displace low- and middle-income residents.

As scholars who study gentrification and social justice, we prefer a model that recognizes all three aspects of sustainability: environment, economy and equity. The equity piece is often missing from development projects promoted as green or sustainable. We are interested in models of urban greening that produce real environmental improvements and also benefit long-term working-class residents in neighborhoods that are historically underserved.

Over a decade of research in an industrial section of New York City, we have seen an alternative vision take shape. This model, which we call “just green enough,” aims to clean up the environment while also retaining and creating living-wage blue-collar jobs. By doing so, it enables residents who have endured decades of contamination to stay in place and enjoy the benefits of a greener neighborhood.

‘Parks, cafes and a riverwalk’ can lead to gentrification

Gentrification has become a catch-all term used to describe neighborhood change, and is often misunderstood as the only path to neighborhood improvement. In fact, its defining feature is displacement. Typically, people who move into these changing neighborhoods are whiter, wealthier and more educated than residents who are displaced.

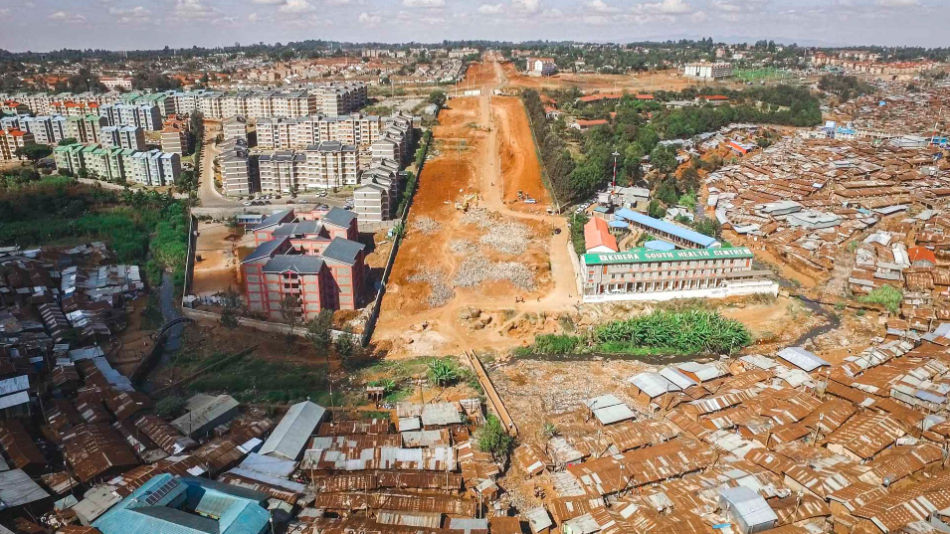

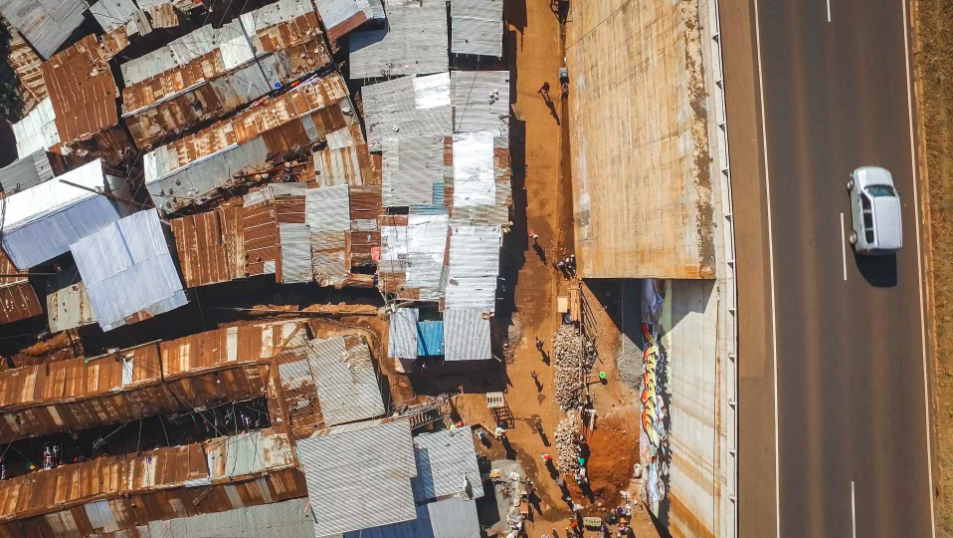

A recent spate of new research has focused on the displacement effects of environmental cleanup and green space initiatives. This phenomenon has variously been called environmental, eco- or green gentrification.

Land for new development and resources to fund extensive cleanup of toxic sites are scarce in many cities. This creates pressure to rezone industrial land for condo towers or lucrative commercial space, in exchange for developer-funded cleanup. And in neighborhoods where gentrification has already begun, a new park or farmers market can exacerbate the problemby making the area even more attractive to potential gentrifiers and pricing out long-term residents. In some cases, developers even create temporary community gardens or farmers markets or promise more green space than they eventually deliver, in order to market a neighborhood to buyers looking for green amenities.

Environmental gentrification naturalizes the disappearance of manufacturing and the working class. It makes deindustrialization seem both inevitable and desirable, often by quite literally replacing industry with more natural-looking landscapes. When these neighborhoods are finally cleaned up, after years of activism by longtime residents, those advocates often are unable to stay and enjoy the benefits of their efforts.

The River Walk in San Antonio, Texas, is a popular shopping and dining area catering to tourists

Tools for greening differently

Greening and environmental cleanup do not automatically or necessarily lead to gentrification. There are tools that can make cities both greener and more inclusive, if the political will exists.

The work of the Newtown Creek Alliance in Brooklyn and Queens provides examples. The alliance is a community-led organization working to improve environmental conditions and revitalize industry in and along Newtown Creek, which separates these two boroughs. It focuses explicitly on social justice and environmental goals, as defined by the people who have been most negatively affected by contamination in the area.

The industrial zone surrounding Newtown Creek is a far cry from the toxic stew that The New York Times described in 1881 as “the worst smelling district in the world.” But it is also far from clean. For 220 years it has been a dumping ground for oil refineries, chemical plants, sugar refineries, fiber mills, copper smelting works, steel fabricators, tanneries, paint and varnish manufacturers, and lumber, coal and brick yards.

In the late 1970s, an investigation found that 17 million gallons of oil had leaked under the neighborhood and into the creek from a nearby oil storage terminal. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency placed Newtown Creek on the Superfund list of heavily polluted toxic waste sites in 2010.

The Newtown Creek Alliance and other groups are working to make sure that the Superfund cleanup and other remediation efforts are as comprehensive as possible. At the same time, they are creating new green spaces within an area zoned for manufacturing, rather than pushing to rezone it.

As this approach shows, green cities don’t have to be postindustrial. Some 20,000 people work in the North Brooklyn industrial area that borders Newtown Creek. And a number of industrial businesses in the area have helped make environmental improvements.

Just green enough

The “just green enough” strategy uncouples environmental cleanup from high-end residential and commercial development. Our new anthology, “Just Green Enough: Urban Development and Environmental Gentrification,” provides many other examples of the need to plan for gentrification effects before displacement happens. It also describes efforts to create environmental improvements that explicitly consider equity concerns.

For example, UPROSE, Brooklyn’s oldest Latino community-based organization, is combining racial justice activism with climate resilience planning in Brooklyn’s Sunset Park neighborhood. The group advocates for investment and training for existing small businesses that often are Latino-owned. Its goal is not only to expand well-paid manufacturing jobs, but to include these businesses in rethinking what a sustainable economy looks like. Rather than rezoning the waterfront for high-end commercial and residential use, UPROSE is working for an inclusive vision of the neighborhood, built on the experience and expertise of its largely working-class immigrant residents.

This approach illustrates a broader pattern identified by Macalester College geographer Dan Trudeau in his chapter for our book. His research on residential developments throughout the United States shows that socially and environmentally just neighborhoods have to be planned as such from the beginning, including affordable housing and green amenities for all residents. Trudeau highlights the need to find “patient capital” – investment that does not expect a quick profit – and shows that local governments need to take responsibility for setting out a vision and strategy for housing equity and inclusion.

In our view, it is time to expand the notion of what a green city looks like and who it is for. For cities to be truly sustainable, all residents should have access to affordable housing, living-wage jobs, clean air and water, and green space. Urban residents should not have to accept a false choice between contamination and environmental gentrification.

Trina Hamilton: Associate Professor of Geography, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York

Winifred Curran: Associate Professor of Geography, DePaul University

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION