A journey across the Land of Kings "Rajasthan, India". See the wonders of Agra, Jaipur, Jodhpur & Jaisalmer through the videographer’s eyes.

I am Congo

Get to know the Congo before you walk through the streets yourself. In this immersive experience, you'll see the vast forest of the congo, the countries colorful style, and break taking shots of life in the city. As part of the "I am" series, videographers spent time in the Congo meeting local artisans, traders and musicians. Their experience, laid out for you here.

Mexico

The videographer is Face du Monde and these are his comments on the video:

“Since I was a kid, it always has been a dream of mine to see "El dia de los Muertos" in Mexico. So last October my friend Max and I decided to travel there. It was my second time in this country I really fell in love with. We spent 3 weeks travelling around Quintana Roo, Yucatán and Campeche states. I made this video to show how this country has his own culture, his own history that you will find nowhere else in the world. "El dia de los Muertos" is an event everybody should see once in his life, it really represents the Mexican soul. I would like to thank all amazing people I met there who made this journey unforgettable.”

People crowded in Rock Palace, Yemen. stepnout. CC by 2.0

YEMEN: A Call for Action: The Worst Humanitarian Crisis in the World

War has torn Yemen apart. According to the 2019 Humanitarian Needs Overview for Yemen, “The humanitarian crisis in Yemen remains the worst in the world”. It states that “An estimated 80 per cent of the population – 24 million people – require some form of humanitarian or protection assistance, including 14.3 million who are in acute need. Severity of needs is deepening, with the number of people in acute need a staggering 27 per cent higher than last year”. This devastating famine is a consequence of the Yemen civil war that started in 2015 and has been ongoing since.

The civil war broke out in 2015 between two factions of Yemen: the armed movement of the Houthi and the Yemeni geovernemnt led by Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi. The fighting started over legitimization of who actually runs Yemen and who gains mass support. Their feud, though, has resulted in their country becoming one of the worst humanitarian crises currently in the world. It has left thousands of adults and children “food insecure”, an official term to identify the starving people in the country. According to an article by the UN, “During the past four years of intense conflict between Government forces and Houthi rebels have left tens of thousands dead or injured including at least 17,700 civilians as verified by the UN”. These people have lost their lives because of a war that took their resources.

In a video by CNN reporter, Sam Kiley, Kiley asked local businessman, Hussein Al-Jerbi, if he thought it was surprising that Yemen is having a problem with hunger. Al-Jerbi responded with, “Not [a] problem - it is a disaster, it is a disaster”. The famine in Yemen is a direct example of what war can bring to a country. The economy has become so poor that the people of Yemen have resulted to selling Khat - an oral drug. In the same video, Sam Kiley interviewed farmer Mounir Al-Ruba’i about why he grows he grows Khat, Al-Ruba’i states, “We only make a profit from Khat - other crops do not cover our home expenses. This is the only crop that would cover our daily and annual expenses.”

The UN and UNICEF have on going sites and systems that allow you to donate to the crisis. While the UN focuses donations on multiple issues, UNICEF provides direct support to the children that are growing up or being born into this humanitarian crisis. On the UNICEF page where you can donate, their call to action states, “An estimated 360,000 children under age 5 are acutely malnourished and fighting for their lives”. An instagram account, @wearthepeace, made a post explaining that if reposted on their story or account, the people running the account would donate meals to Yemen. They not only have a link in their bio for anyone who wants to donate can, but their campaign, which is a post explaining that for every 10 times the post is reposted, they will donate $1 to the Yemen crisis. Their intention behind the post was to not only raise money, but also raise awareness about the humanitarian crisis so people are talking and doing something about it. With their 107K following, they have done just that. Their donations also include food baskets (the contents of those food baskets are listed in the post). On June 14th, the post was removed over controversy that the campaign was a hoax, but after contacting Instagram and providing proof of their legitimacy, their post was reinstated on June 23rd. To this day, they are still spreading awareness and raising funds for the Yemen crisis.

This is considered one of the worst humanitarian crises in the world because of the amount of innocent lives it is affecting. But we can help. With a donation, no matter how big or small, to the organizations listed above, we can make sure the funds are going to the right place. If donation is out of the question, please share and repost articles and stories about Yemen, specifically the account that donates once you repost. Ensuring that this crisis is not forgotten or swept under the rug will aid the people of Yemen.

The livelihood of the Yemeni people are at stake. With consistent awareness and donations, we can help aid the Yemeni people and ensure the war does not destroy them.

OLIVIA HAMMOND is an undergraduate at Emerson College in Boston, Massachusetts. She studies Creative Writing, with minors in Sociology/Anthropology and Marketing. She has travelled to seven different countries, most recently studying abroad this past summer in the Netherlands. She has a passion for words, traveling, and learning in any form.

An Ethiopian farmer in the Amhara highlands outside the historic village of Lalibela. EPA/Stephen Morrison

Why Abiy Won’t Succeed Unless He Listens to Ethiopia’s Majority – its Rural People

Abiy Ahmed has made a raft of radical steps since taking over as Ethiopia’s prime minister in April 2018. He has redressed some of the wrongs committed by his own party, brokered peace with Eritrea and released political prisoners. Abiy has also invited opposition political groups back into the country and overseen the reunification of a splintered Orthodox church.

Abiy’s approach is summed up by his philosophy of medemer, or inclusivity and unity. His reforms have led millions to believe that positive revolutionary change is on its way. But there’s one significant group he has yet to address: the rural majority.

More than 80% of Ethiopians live in rural villages beyond the reach of mass media. So far, they have not been included in the ongoing national conversation. Yet, they contribute significantly to the economy by providing 85% of all employment and 95% of agriculture outputs.

Past governments exacted revenue from rural people but ignored their voices in policy making. During Haile Sellasie’s rule, rural people had to pay a share of their produce to their chiefs in order to keep their land. Mengistu Haile Mariam’s marxist regime introduced land reform based on its communist ideology but required rural people to fund and fight its wars.

The current government came to power with the promise of ensuring food security but it politicised ethnic identity and is currently focusing on rapid economic growth through the commercialisation of agriculture.

Consistently, Ethiopian governments created their own policies without listening to rural people first. But there can never truly be any hope for the country’s future if the forgotten majority continue to be ignored.

The reality for rural people

Since the 2000s, Ethiopia has been praised for fast economic growth. The government celebrates small holding farmers as the drivers of its success. But, so far, economic growth has not translated into a better life for the rural poor.

In 2015, some 18 million (20% of the total population) were affected by drought, the worst in 50 years. This year alone, 7.4 million, mostly children and women, are in need of help.

In addition to natural disasters, rural people are victims of an ill-conceived land policy. Land is controlled by the government. Farmers don’t own their land. They’re simply granted the right to use it. Land scarcity is a major problem. More than 60% of rural households survive on less than one hectare of land. A lack of access has led to young people being uprooted from rural areas.

Yet, the government leases large tracts of land to private investors to spur economic growth. From late 1990s to 2008, almost 3.5 million hectares of land was rented to investors at very low prices for a period of up to 99 years. The government advertises that 11.5 million hectares of land is currently prepared for private investment. Investors mainly focus on producing flowers, biofuel, and other export products. These in turn cause water shortages and environmental problems.

In a country of 103 million, where the survival of 80% of the people depend on subsistence agriculture, the priority given to private investors raises significant concerns.

Urban Ethiopians view foreign investors as a sign of progress. They see this land-grabbing as a sign of development. Yet the commercialisation of agriculture is being used to concentrate wealth in the hands of a small ruling class. It has increased food prices for the poor.

In Gambella, 70,000 people have been moved to new areas. Many more are believed to have been moved off their ancestral lands to make way for the country’s vision of becoming the world’s leading sugar producer.

Abiy has yet to address any of these issues. So far, he has shown no signs that he intends to change the government’s land policy.

Colonial mindset

One of the major hurdles facing the forgotten rural majority is the colonial mindset of many urbanites and people in power. The exclusion of rural people from the affairs of the state is not new. But it has intensified since 1974.

Traditionally, rural Ethiopians had institutions that influenced the power of their leaders. Leaders needed to fulfil and be accountable to tradition. They were respected more than feared.

But since the beginning of 20th Century, Ethiopian leaders sought to gain global legitimacy by bringing western institutions and knowledge to the country, excluding traditional knowledge and Ethiopian languages from higher education. Students learnt western history, culture and philosophy in English, and started to internalise the western gaze that saw Ethiopian traditional knowledge and institutions as primitive.

This colonial mindset, that has internalised western knowledge as progressive and Ethiopian knowledge as backward, is one of the major factors excluding rural people from reform and political debate. Rural people are seen as antithetical to progress, or simply ignorant of how things can be done better. For example, ten years ago the World Bank blamed Ethiopia’s “backward farming system” for acute food shortages.

Across the country, rural people understand land not as a natural resource that can be converted into cash, but as a source of life, spirituality, culture, and identity. Any cursory study of land-grabbing in Ethiopia shows that government policy has resulted in ongoing violence against the livelihood and culture of rural people. Rural people still feed the majority of the population; protecting them protects the rest.

Everything Ethiopians are proud of today, from their ancient culture to their independence from colonialism, came from the culture of rural life. It is this rich cultural knowledge that should be drawn upon, rather than continually looking out to the west.

Despite all of Abiy’s inspirational reforms, there can be no true progress for Ethiopia without listening to the rural majority.

YIRGA GELAW WOLDEYES is a lecturer of Human Rights at Curtin University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Feel The Sounds of Senegal

A 3 week trip in Senegal allowed Cee-Roo to capture the culture of a people and feel the power and importance of music in a country where the joy of living takes over poverty.

Feel The Sounds of Senegal

A 3 week trip in Senegal allowed filmmaker Cee-Roo to capture the culture of a people and feel the power and importance of music in a country where the joy of living takes over poverty.

Two Years in Cambodia

It all started on a tuk tuk ride…

I had just landed in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, after covering the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda) in Tacloban, Philippines.

Although I had never been there before, Cambodia was already the place I had decided to call home for the next year, or more. It was May 2014. The sky was still painted in black when I got off the plane and was engulfed by the warm and humid weather that, as I would learn over the following months, so much characterizes the country, especially at that time of the year.

As I exited the airport, all I could see was a chaotic frenzy of hands waiving and pointing to their tuktuks. They were all wearing similar clothes – sandals, a pair of pants and a shirt – and they all had big, unequivocally authentic smiles on their faces.

I don’t know if by instinct or pure luck, I ended up going with a driver who would later become a great friend of mine. Bunchai. His tuktuk was painted in red and it was so carefully and effusively decorated that it reminded me of the carnival parades we have in my home country Brazil.

As we cruised the quiet streets towards Tuol Tom Poung, a central neighborhood where a fellow photographer would host me until I found my own place, I just couldn’t believe in what I was experiencing. What was once just a dream was now a reality. I was indeed beginning a new life in Southeast Asia.

The Sun was just rising above the Tonle Sap and people were already doing choreographic exercises along the river promenade. Buddhist monks were walking around with their orange and red robes – some of them holding iPads -, and entire families were impressively balancing on the top of tiny and seemingly fragile motorbikes.

I fell in love immediately. I felt at home.

During the two years I was fortunate to spend in the country I obviously saw extreme poverty and shocking social-economic inequality. I witnessed – and documented – several and horrifying human rights violations. I learned about the atrocities and crimes against humanity committed by the Khmer Rouge, which took the lives of over 2 million people.

But I also saw remarkable resilience and an inspiring ability to find joy even in the most challenging circumstances. I saw generosity and kindness. Faith and Gratitude. Compassion and Happiness. I saw a younger generation trying to leave the past behind and embrace the future.

I explored remote and impressive temples from the 12th century; I spent relaxing days at paradisiac islands and sleepy river towns; I zigzagged through the chaotic traffic in Phnom Penh with my 1989 Vespa; and I had way too many beers with my local neighbors (most of them tuktuk drivers), who would always invite for a beer every time they saw me getting to or leaving my house. They never accepted a No for an answer.

I worked for magazines and I cooperated with many local and international NGOs. I photographed every single day during the time I was there and through this daily wanders I learned to see the extraordinary in the seemingly ordinary.

Cambodia has taught me lessons that I will forever carry on my heart and I hope I will have the chance go back in the near future. The recent news that the only opposition party has been dismantled is certainly worrying and it makes me think of all the friends I left there.

If up until recently Hun Sen – who has been in power since 1985! – at least tried to keep a democratic appearance to his government, it seems that now he is no longer concerned about exposing the true face of his (totalitarian) regime. Cambodians, who have gone through the horror of Khmer Rouge just a few decades ago, certainly deserve better and brighter days.

Bunchai, the first friend I made in the country, is still working at his day job and driving his tuktuk in the evenings and early mornings. The day we took that same way to the airport, but on the opposite direction, two years after our first encounter, was unusually cloudy and gray. I don’t remember seeing much during our ride. Perhaps I had too many thoughts and memories going through my mind…

When we finally reach the airport, after a trip that seemed to have last for an eternity, I give Bunchai a big hug and just can’t hold my tears. I ask him to take care of himself and his family, and I tell him that if he ever needs any help he must call me immediately.

He gives me that very same smile he had greeted me with two years earlier, and says, with both determination and confidence:

“No worry, my friend. I will be fine! See you soon!”

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON ROAM MAGAZINE.

BERNARDO SALCE

Bernardo Salce is a a Brazilian photographer whose work seeks to celebrate cultural diversity and raise social-environmental awareness. Having previously lived in Cambodia and Colombia, he is now based in San Diego, California. You can follow his work @bernardosalce.

INDIA: Timelapse in Mumbai and Bangalore

This short film is a timelapse throughout Mumbai and Bangalore. The film shows India's cultures in the cities and beaches. Through aerial shots and video on the ground, the video shows India to all viewers.

Gulf of Thailand

A travel to the islands of the Gulf of Thailand, discovering 3 contrasting places : Koh Samui, Koh Phangan and Koh Tao. Three islands with immaculate beaches, jungle, venerated temples, great aquatic life and of course the smile of Thai people.

Filmed & Edited by Gilles Havet

Great minds discuss ideas, average minds discuss events, small minds discuss people.

Visions of Kenya

A long time went by before I was able to understand this trip. Sometimes, the present is not understood until it becomes the past. Kenya belongs to a continent of origins, remote and distant, and for now, for better or worse, many of its vast and beautiful rural areas remain far from the globalised world.

In a matter of two weeks I had organised everything. Bought the tickets from Buenos Aires to Mombasa, got the necessary vaccines, packed my things and let my friends know I was leaving. “I’m going to Kenya for a month, alone, just my backpack and camera, nothing else.” It was a long flight to Mombasa. I was very tired and somewhat nervous about it all. At the airport in Mombasa the image of a rhino gave me goosebumps. I had arrived.

— Mombasa —

The first morning I was woken by the heat and the unrelenting racket made by the many crows that inhabit Mombasa. I looked outside the window to see Africa for the first time: bonfire smoke on the sides of the street, women selling fresh fruit right outside our building, next to them, I saw other women with beautiful braids in their hair, and a little further away, a man selling plants. Here, life takes place on the streets.

He was selling onions on the side of the road to Nairobi

I enjoy travelling alone and getting to know different cultures, in the most simple and genuine way possible, simply by being there, and merely observing. Trying not to alter what I see, to be inconspicuous. But in Mombasa, I was noticed right away. I am a white Argentinian, in a city where almost everyone is black. It was impossible to remain unseen.

Sunday morning is a social time for families at the public beach

The first few days were filled with nervousness and anxiety. I was alone in a place completely different to my own, full of tension and expectations about what the trip might become. Was I going to be able to adapt to Africa? I just wanted to let go, come to know the locals, let down my resistance, and give myself up to whatever had to happen.

Eddie lives inside a garbage container in Mombasa. The day I left Kenya, I gave Eddie all of my clothes.

Two days went by and I decided it was time to get out of the city. Venturing into the more rural areas of Kenya would be better than staying in Mombasa. Leaving my big backpack behind, I grabbed my camera, my flip flops, swimming trunks, and my kikoy — a traditional man’s wraparound worn on the Swahili coast of East Africa, especially in Kenya. It protected me from the sun and from the stares too. I took a tuk-tuk to the south of town, then a ferry, and then a three-hour matatu — one of Kenya’s colourful buses. My destination was Wasini Island, a small island in the south, where people usually snorkel for a few hours and then leave. I wanted to stay, at least for a few days.

School children on the road from Mombasa to Kilifi / She was sleeping in the matatu along the way.

I was greeted by Abdullah, who was surprised to meet a foreigner who wanted to stay longer than a few hours. I got on a small boat and crossed the island with two guys who were carrying huge machine guns, which they used to absentmindedly scratch their feet and faces — I had never seen such big weapons.

Baobab tree lit up at night

— Wasini —

Wasini is a coral rock island that during its hey-day was a popular summer destination for retired and wealthy Europeans who wanted to enjoy the heat and beaches of Kenya. The day I arrived, there was just one dutchman and me, and the rest of the island was a small fisherman’s village. Abdullah cooked a fish for me with great care, and later made me visit the “tourist attractions,” which meant very little to me.

Coral stones in the Indian Ocean

I met someone who said he would take me over to the other side of the island along a path that would pass through the mangroves. I told him I had very little to tip him with, as I had left all my money in Mombasa. He gently insisted on taking me and I followed him. We walked through the island for a long time and I started to worry, thinking about where this stranger was actually taking me. The sun had started to set and as is common in many places in Kenya, there was no electric light.

We were crossing the path with this guy, while a fisherman was preparing his bait. I asked to take a picture of him, and he accepted.

We kept on walking until we finally reached the other side of the island. The mangrove trees continued all the way into the sea, and it was a very beautiful sight. I calmly took a breath, my guide had not deceived me. At that moment I felt that if I had managed to get to such a remote place with a complete stranger, then it meant that the rest of my trip would turn out alright. It was a feeling I had. Complete trust.

Among the mangroves

— Kilifi —

I spent a few days in Wasini and then returned to Mombasa to continue northwards along the coast, towards Kilifi. In Kilifi there was a very impressive hostel, but when I entered I had the feeling of being out from what I have been seeing. Luckily, I decided to walk towards the beach, where I found a beautiful sunset.

Little sisters playing together in a tree near their home.

The beach was deserted. It was actually an estuary, very serene. I loved rural Kenya, so far away from the cities. As I sat with my camera I saw a kid walking in the distance. As he approached me I waved, then he waved back and continued to walk. A few hours later, the kid returned and I went over to have a chat. He responded by asking me if I knew how to hunt crabs. His name was Buda.

Portrait of Buda

We became friends and I met all of his brothers and sisters as well. They were many, and lived on the coast with their aunts and cousins. Most families in Kenya live with their extended family, and the women are in charge of the houses. Men are absent most of the time, often spending time with friends, away from their homes.

Full of joy in the ocean / Fishermen and family in the early morning

I quickly became very fond of Buda and his siblings, and they became fond of me. Every time I came down to the beach, they would arrive to greet me. I spent whole days on the beach, sometimes helping them gather wood for making fires, or finding things their mother had asked for — I learnt a lot about their culture and way of life, which was not always easy. Buda and Nuzrah were the eldest siblings and spoke better English. They taught me a lot of words in Swahili, their native tongue.

Portrait of Nuzrah

One of the days we spent together I brought them a football, a water gun and a jumping rope. We played with them, they taught me beach games, and every now and then we would all go for a swim. It was with great grief that I said goodbye to these children, as I had to continue travelling towards the west of the country. They stayed with me until I left, and their mother also came to say goodbye.

Portrait of Buda / Jumping rope / Portrait of Mwanaisha

— Amboselli —

I took a tuk-tuk back to Mombasa, thinking about everything I was experiencing. It felt so powerful and different, making me reflect on my own life, and how grateful I was for the opportunity to travel. The following dayay I left for Amboselli National Park. Enormous and open, there were no fences around it. Animals are not easy to see. You might spend a whole day walking around and only encounter a few zebras.

Morning of the Zebras

But the immensity and beauty of the landscape was truly dazzling to me, sometimes reminding me of my native Patagonia, similarly wild and empty in its own way. I also thought about the devastation humans have caused to the natural environment, and the complex challenges local and international communities face as they attempt to tackle and reverse this.

Afternoon of the elephants

I spent my whole childhood fascinated by documentaries on Animal Planet, or Discovery Channel. I could not quite believe I was there, in these vast landscapes. The animals were so big, so strong. They had very little to do with the image I had of elephants in zoos or television. And the trees, they were so magical, I really have no words to describe them.

Masai walking in the early morning / Just a beautiful tree, in my first moments in the park

A long time went by before I was able to understand this trip. Sometimes, the present is not understood until it becomes the past.

When I travel, I seek to explore places that will surprise and challenge me, and from that surprise create beautiful experiences and photographic visions of what I have witnessed. Kenya belongs to a continent of origins, remote and distant, and for now, for better or worse, many of its vast rural areas remain far from the globalised world.

Early morning at Tsavo. There is always magic in the first hours of the day.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON MAPTIA.

FRAN PROVEDO

Fran Provedo is a photographer and Architect from Argentina. Passionate about nature, and what is invisible in it.

8 People Who Broke the Law to Change the World

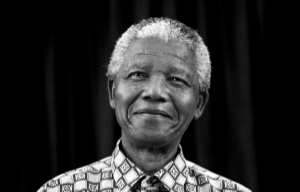

1. Nelson Mandela

Nelson Mandela is, hands down, one of the most important and celebrated figures of our lifetime.

Mandela represents equality, fairness, democracy and freedom in an often unequal, unfair and undemocratic world. But he wasn’t always seen like this…

Twenty-five years ago he was getting his first taste of freedom after being imprisoned for 27 years. Yes, you read that right. For what? What could he have done to get such a long sentence? Well, he stood up for what he believed. In 1942 he joined the African National Congress and fought against apartheid in South Africa, and was imprisoned for sabotage.

Without Nelson Mandela’s commitment to the abolition of apartheid in the face of oppression and imprisonment, the world could be a very different place. It is because of Mandela, and others like him, many more people live a free and fair life.

To honor his bravery and determination, we take a look at 7 other brave and committed people who have been prosecuted or persecuted for standing up for what they believe in:

2. Aung San Suu Kyi

Aung San Suu Kyi has become an international symbol of peaceful resistance in the face of oppression.

Now the Burmese opposition politician and chairperson of the National League for Democracy in Burma, she spent 15 years under house arrest for advocating for democracy.

Suu Kyi, who was heavily influenced by Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violent protest, helped to found the National League for Democracy. Because of her campaign for democracy in military-ruled Myanmar (Burma), she was detained and kept imprisoned by the government, as it viewed her as someone “likely to undermine the community peace and stability” of the country.

She was offered freedom if she left the country, but she refused to let her party down and stayed in Mynanmar.

In one of her most famous speeches, she said: “It is not power that corrupts, but fear. Fear of losing power corrupts those who wield it and fear of the scourge of power corrupts those who are subject to it.”

3. Liu Xiaobo

Liu Xiaobo is a Chinese writer, professor, and human rights activist who called for political reforms and the end of communist single-party rule. He is a political prisoner.

Liu was detained in 2008 because of his work with the Charter 08 manifesto, which called for an independent legal system, freedom of association and the end of one-party rule.

He was arrested in 2009 on suspicion of “inciting subversion of state power”. He was sentenced to eleven years’ in jail and two years’ deprivation of political rights.

During his fourth prison term, he was awarded the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize for “his long and non-violent struggle for fundamental human rights in China.”

He is the first Chinese citizen to be awarded a Nobel Prize of any kind while residing in China and is the third person to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize while in prison or detention, after Germany’s Carl von Ossietzky (1935) and Aung San Suu Kyi (1991).

4. Mahatma Gandhi

India’s great independence leader first went to prison in 1922 for civil disobedience and sedition after a protest march turned violent, and resulted in the deaths of 22 people. The incident deeply affected Gandhi, who called it a “divine warning’.

He was released from prison after serving 5 years of his 6 year sentence, and went on to become the most famous advocate of peaceful protest and campaigning in the world.

Gandhi famously led Indians in challenging the British-imposed salt tax with the 400 km Dandi Salt March in 1930, for which he was imprisoned for a year without trial, and later lead the Quit India Movement, calling for Britain’s withdrawal. He was arrested many times but never gave up. An advocate until the end, Gandhi sadly paid for his beliefs with his life when he was assassinated by a militant nationalist in 1948.

5. Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King had a seismic impact on race relations in the United States, as the face of the Civil-Rights movement in the 1950’s.

Through his activism, he played a pivotal role in ending the legal segregation of African-American citizens, as well as the creation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. King received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, among several other honors.

King was arrested 5 times, and wrote his second most influential speech whilst in prison in 1963 for protesting against the treatment of the black community in Birmingham, Alabama. Letter From Birmingham Jail, which was written on the margins of a newspaper and smuggled out of the prison, defends the strategy of nonviolent resistance to racism, arguing that people have a moral responsibility to break unjust laws.

Tragically, in 1968 he was assassinated in his hotel at the age of just 39.

6. Rosa Parks

Rosa Parks was an African-American Civil Rights activist who became famous when she stood up for what she believed – by sitting down. On the evening of December 1, 1955, Parks was sat on a bus in Alabama, heading home after a long day of work.

During her journey she was asked by a conductor to give up her seat to a white passenger, but she refused, and she was arrested for disobeying an Alabama law requiring black people to relinquish seats to white people when the bus was full. Her arrest sparked a 381-day boycott of the Montgomery bus system. It also led to a 1956 Supreme Court decision banning segregation on public transportation.

7. Susan Brownell Anthony

Or Susan B as some gender studies students know her as, was an American social reformer and feminist who played a pivotal role in the women’s suffrage movement.

Actively involved in social justice from a young age, Anthony and friend Elizabeth Cady Stanton, founded the Women’s Loyal National League, which conducted the largest petition drive in the nation’s history up to that time, collecting nearly 400,000 signatures in support of the abolition of slavery.

In 1866, they initiated the American Equal Rights Association, which campaigned for equal rights for both women and African Americans, and in 1872, Anthony was arrested for voting in her hometown of Rochester, New York, and convicted in a widely publicised trial. Although she refused to pay the fine, the authorities declined to take further action. In 1878, Anthony and Stanton arranged for Congress to be presented with an amendment giving women the right to vote. Popularly known as the Anthony Amendment, it became the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920!

8. Roxana Saberi

Roxana Saberi is an American journalist who was arrested in Iran and detained for 100 days after being falsely accused of espionage. She had been living in Iran for six years, doing research for a book that she hoped would show a more complete and balanced picture of Iranian society. Under pressure and being threatened with a 10-20 year sentence or even execution, Roxana falsely confessed to being a spy. She quickly realized this was a mistake and recanted her confession – knowing this would jeopardize her freedom. Instead of freeing her, her case was sent to trial, sentencing her in eight years of prison.

“I would rather tell the truth and stay in prison instead of telling lies to be free.”

After her trial, she began her hunger strike – only drinking water with sugar. After two weeks, Roxana’s attorney appealed her conviction. She was released from prison after an appeals court cut her jail term to a two-year suspended sentence.

“I learned that maybe other people can hurt my body, maybe they could imprison me, but I did not need to fear those who hurt my body, because they could not hurt my soul, unless I let them.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON ONE.ORG

CLEA GUY-ALLEN

Clea hails from Brighton, United Kingdom and was the UK Global Citizen Editor. Now she works as the digital coordinator for ONE, a campaigning and advocacy organization to end extreme poverty and preventable disease.