A group of friends started a journey to Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Uruguay, Paraguay and Southern Brazil in their old and rusty Land Rover. They encountered lots of winds, emptiness, pampas, bustling cities, animals, deserts and waterfalls—all wrapped up in just under 6 minutes. Enjoy the ride!

Latin America is the Most Dangerous Region for Environmentalists

In 2019, 212 land and environmental defenders were killed worldwide. Over two-thirds of these killings took place in Latin America.

Since the adoption of the Paris climate accord in December 2015, an average of four environmentalists have been killed each week. Each year, around 60% of these murders take place in Latin America. These killings span different economic and environmental sectors, from agribusiness to oil and gas, and are traced to different perpetrators, including organized crime groups, paramilitary groups, police and contract killers linked to businesses. Latin America has so far seen little government crackdown on unauthorized practices that harm the environment, like logging and deforestation, and governments have been unsuccessful in preventing these illegal businesses from coming into conflict with environmentalists.

Global Witness, an organization dedicated to exposing the connections between natural resources, conflict and corruption, releases an annual report on the killings of land and environmental defenders worldwide. Since Global Witness began this report in 2012, Latin America has consistently ranked as the most dangerous region for environmentalists.

In 2019, the number of murdered environmental defenders reached a new high of 212. Sixty-four of these deaths were in Colombia, making it the country with the most environmental defenders killed. Brazil, Mexico and Honduras ranked third, fourth and fifth for number of environmental defender deaths. According to the report, mining, agribusiness and logging were the deadliest sectors for environmental activists. All three are sectors that contribute heavily to industrial emissions and thus face strong criticism for their impact on the ever-worsening climate crisis.

The 2019 Global Witness report also found that, as in previous years, Indigenous activists face disproportionate risk. Forty percent of murdered environmentalists around the globe belong to Indigenous populations, despite these groups making up less than 5% of the world’s population. The risk to Indigenous environmental activists in Latin America is no different; many of Latin America’s environmental activists are members of the Indigenous population, like Berta Caceres, whose 2016 murder following her vocal opposition to a hydroelectric project sparked international outrage. In the first two months of 2020, at least 11 Indigenous activists were killed in Latin America.

The 2020 Global Witness report on environmental defender killings has not yet been released, but the Council on Foreign Relations reported in April 2020 that high-profile killings of environmentalists in Latin America had accelerated during the first half of the year. It is likely that the number of environmentalists killed in Latin America increased, and will continue to increase unless preventive actions are taken.

Recently, countries in Latin America and the Caribbean took steps toward protecting the rights of environmental activists through the Escazu Agreement, which entered into force on April 22, 2021. The agreement, which was first adopted in 2018, introduces specific provisions to defend the human rights of environmentalists. The agreement has now been adopted by 24 countries and ratified by 12, officially putting its new provisions into effect. The Escazu Agreement is only the start of a solution, however. Governments need to not only protect environmentalists, but to support their mission of defending ecosystems while preventing environmentally destructive projects.

Rachel Lynch

Rachel is a student at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY currently taking a semester off. She plans to study Writing and Child Development. Rachel loves to travel and is inspired by the places she’s been and everywhere she wants to go. She hopes to educate people on social justice issues and the history and culture of travel destinations through her writing.

Through the “Open Veins of Latin America” | Bogota to Lima by Bicycle

Photo essay by photographer Bernardo Salce, who rode 4,000 km on his bicycle from Bogota, Colombia to Lima, Peru

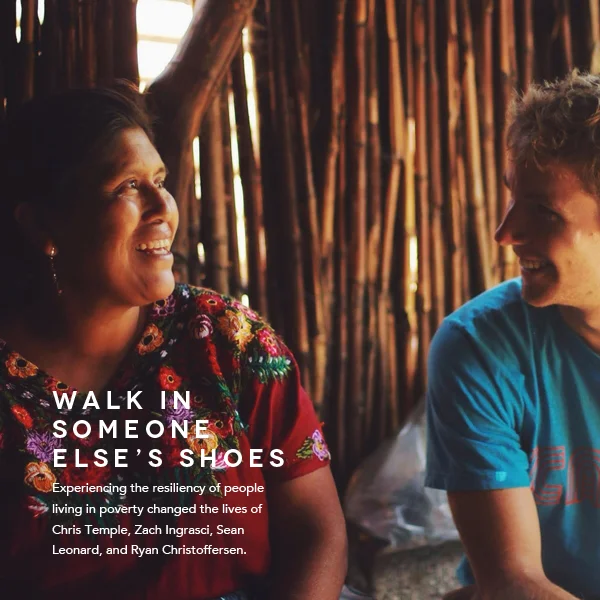

Read MorePhoto credit: Living On One

Living on One Dollar: Four Students Fight Against Global Poverty

Sometimes all we need is to get away and gain a bit of perspective, whether it is to your old tree house in your back yard, your favorite coffee nook downtown, or a completely different country. Taking a moment to recognize the elements of life and how blessed you are can bring infectious happiness and gratitude, so share this pleasure by immersing yourself in the lives of others and trying to see the world from their point of view. That’s what four students from Claremont McKenna College did - they traveled to Pena Blanca, Guatemala to get a true perspective of extreme poverty and engage with the people living in this village who struggle to survive on $1 per day. Experiencing the resiliency of people living in poverty changed the lives of Chris Temple, Zach Ingrasci, Sean Leonard and Ryan Christoffersen by grounding them from our materialistic, over-consuming reality and allowing them to learn about the everyday hardships that people must face simply just to survive another day. Now, these four men hope to change the lives of the 1.1 billion impoverished people who live on $1 a day by raising awareness, fostering inspiration and encouraging action.

Chris and Zach were kind enough to answer a few questions about the process that led to the creation of their newly released documentary ‘Into Poverty: Living On One Dollar’, which details their travels to Pena Blanca, their experiences of living on $1 per day for eight weeks, the issue of global poverty and how you can help.

Q | How did you come up with the idea for the trip and actually make it a reality?

We were studying economics and international development in school, but the issues we were reading about seemed so far from our daily reality. We constantly heard the overwhelming statistic that 1.1 billion people live under $1 a day, but growing up in Connecticut and Seattle, had little ability to understand the reality of life at that level. So we came up with the concept to live under $1 a day for two months ourselves. We knew that we'd never be able to truly replicate poverty but we did believe that this would be a valuable experience.

Having an idea and making it a reality are two very different things. We developed the idea over a 10 month period and applied for funding from 9 different sources but got rejected from all of them. We had no track record of making films and the project was different and potentially dangerous – making it difficult for someone to fund. Finally about a month before leaving, we got $4,000 from the Whole Planet Foundation, which was enough for our plane tickets and $1 a day each while there. Actually going was a difficult decision to make though. My family wasn’t particularly supportive and there was a lot of pressure to get a traditional internship with a consulting firm or investment bank.

Q | How did you prepare yourselves for a trip that is so different from the reality that you are used to?

Looking back, we were horribly unprepared for the trip, both physically and emotionally. But I’m not sure how we could prepare for what the following few months were going to bring. It may have been to our advantage that we didn’t have much time to think about the trip right before going because we were so busy with end of the year exams at school.

Photo credit: Living On One

Q | Why did you choose Pena Blanca for this experience?

We chose Guatemala because I (Chris) had been lucky enough to travel there a few years before and had fallen in love with the culture and people, especially the rural areas. When we thought of the idea for the documentary, we were studying economics in school, and were shocked to learn that in Guatemala almost 50% of the population lives in poverty and in rural areas 75% of the indigenous population lives in poverty. This was representative of rural poverty in many parts of the world, and an unimaginable problem that we wanted to learn more about.

We chose Pena Blanca specifically because we knew people at a nearby non-profit who had been to the community before, knew the average income, and knew that it was a safe community.

Q | At any point in the trip did you want to give up? How did you persevere through the tough times?

I (Zach) remember one morning when I woke up on our dirt floor after being bitten by fleas all night. I didn't know if we were going to have enough money for food that day let alone medicine for a parasite that Chris had just contracted from contaminated drinking water.

The discomfort of the dirt floor and fleas was definitely challenging but it was the stress of having a small, irregular income and not knowing what illness or disaster was going to hit us next that was really the hardest part.

These challenges made us realize just how innovative and strong the poor have to be to even survive. Seeing our neighbors strive to improve their lives, in the face of such hardship, inspired us to stay the 56 days and do everything we can to give back. We really built life-long friendships with them – friendships that transcend just this film – which is the most rewarding part. They inspired us to create this film that would inspire action through hope, not through guilt.

Q | Did you ever feel guilty knowing that you would return home in a few weeks to electricity, running water, an actual bed, etc.? How did you deal with those feelings?

The hardest part about the whole trip was leaving and knowing that our neighbors faced an unpredictable and extremely challenging future. I think a lot of people feel this sense of guilt when they come back from abroad, and they hide from those feelings instead of facing them. It seems like such a shame that we travel and build these amazing relationships and then never follow up again or keep in touch. What has been so lucky about this project is that we’ve been able to go back 3 times to Pena Blanca over the past few years and speak monthly on the phone with Chino, Anthony and Rosa. We’re even friends with Rosa on Facebook!

Technology allows us to stay connected around the world and continue to learn from one another and be there for one another in times of need.

Q | What is your advice for other college students who want to go on a service trip or get active about a topic they are passionate about?

I would encourage everybody to walk in somebody else’s shoes, if only for a few days. Through the experience, you’ll gain empathy for someone else’s reality and never judge, disregard, or ignore a person like them in the future. For me (Chris), I will never see a hotel janitor in the same light. Anthony, one of our neighbors, was one of the most generous and intelligent people I’ve ever met, yet he cleaned hotel rooms for a living. This might not be considered the most accomplished job to some, but his formal job and steady paycheck were the envy of the entire town.

There are so many ways for someone to make a difference in the world. It doesn’t have to be an international service trip, it could be mentoring a low-income student nearby or an environmental project. What’s important is that you give something, your time, your money, or your skills. These actions will help you find your inspiration and lead you down a path you would have never expected. I was going to intern for an investment bank for the summer, but instead went to Guatemala, and my whole life path was changed.

Photo credit: Sean Leonard

Q | Overall, what have you learned from these experiences and how have they changed your life and outlook?

If there’s one thing I walked away with from Guatemala, it’s that small things can have a huge effect on the lives of the extreme poor. By understanding this, we can feel empowered that change is possible.

For billions of the poor it is not a choice to live with less. What is most troubling is not that they live with less material things but that they live with less opportunity to improve their lives. They often don't have access to things we take advantage of everyday like education, financial services, nutrition, healthcare and even access to clean water. For those who have these resources it is our responsibility to join together and make a difference in the world.

One of our closest friends in Peña Blanca is Rosa, a 21-year-old woman, who has this dream of becoming a nurse. Sadly, in the 6th grade, she was forced to drop out of school because her father got sick. Years later, with the help of a microfinance loan of only $200, she was able to start her own weaving business and with the profits, begin paying for herself to go back to school and keep her dream alive. Rosa is one of the smartest, most motivated people we have ever met, all that she lacked was an opportunity to improve her own life.

Learn, Connect, Act.

Learn more about Living On One

Connect via Facebook and Twitter

1. Spread the word. Our film just released for anyone to download it on our website or iTunes.

2. Give a Donation. You can support education, clean water, or microfinance for the community of Pena Blanca by giving to one of our impact partners here: www.LivingonOne.org/changeseries

3. Buy Shirts or Sandals. Our shirts are handmade by the star of our film, Rosa, and help pay for her education. The sandals support the health and education of Guatemalan children like Chino.

4. Contact High School teachers and tell them to show the film and/or bring us to speak so we can create a generation of active global citizens.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN CONSCIOUS MAGAZINE

CARLY LONG

Carly Long is a contributing writer and researcher for various publications, including Conscious Magazine. Her articles have focused on companies that incorporate social good, as well as individuals who work to improve the lives of others. Carly is also a self-taught painter, as she developed an original technique of custom painted photographs.

Systemic Discrimination Against Haitian Workers in the Dominican Republic

Capitol Building in Santo Domingo, DR

In July 2012, I lived within the sugar cane communities of the Dominican Republic, known as the “Bateyes,” as a volunteer for Save the Children, a nonprofit that advocates for children’s rights. Recent media attention to Dominican immigration reform has provoked international criticism for its perceived racial bias, as it threatens to deport thousands of Hatian workers. My experiences on the ground exposed me to some of the hardships that individuals from this region endure. For members of the Bateyes, destitution and food insecurity are systemic challenges that define everyday life. After hours of hard labor under the Caribbean sun, cane cutters earn an average of less than two dollars per day. Walking between the tall sugar stocks on an impromptu tour of a community, a local resident demonstrated the proper way to cut cane. Since the plants are sensitive, agricultural machinery is less effective than individuals with machetes and gardening tools. The man explained that cane cutters leave for the fields at dawn and work until dusk. The only available form of nutrition is the sugar cane, which is absorbed from bits of chewed stock consumed throughout the day.

Cane cutting demonstration in Bateye Margarita

Back in the communities, families stretch their two-dollar income to purchase food such as rice from the sundry store. When fellow volunteers and I asked the kids at a small, under-resourced school what they wanted to be when they grew up, they were excited to share dreams that resembled those of children everywhere: doctors, police officers, astronauts, and beyond. I thought back to the truck of cane cutters I watched disappear into the fields earlier that day and was reminded of the tragic reality that awaits this population: Undocumented in the eyes of the law, these children will either remain in the Bateyes as workers and wives or else be deported to Haiti.

In 2004, Dominican authorities passed an immigration law specifying that children born to undocumented immigrants would be excluded from Dominican nationality. Over the past 50 years, the DR has recruited thousands of Haitian laborers to cut sugar cane under two bilateral agreements signed by the countries in 1959 and 1966. First-person accounts describe a form of modern slavery, in which Haitians were deceived by promises of better opportunities, taken across the border in buses in the middle of the night, then stripped of their papers that declare citizenship status. The impoverished families were left with no alternative but to work in the cane fields and reside in the neglected communities they now call home.

Typical home in Bateye Experimental

After decades of struggle in the Bateyes, a population that is 90% Haitian, a 2013 Dominican Constitutional Court decision reinterpreted the immigration law. This decision altered the law to extend its definition to individuals born between 1929 and 2010, and ordered government officials to revoke citizenship from those who no longer qualified. A naturalization law was passed the same year as a pathway to gain citizenship, but the process was marred with bureaucratic roadblocks and inconsistencies. The deadline to register passed at the end of June 2015: Almost 200,000 individuals remain at risk of deportation back to Haiti.

During my time in the Bateyes, I stayed at a quasi-hostel run by a missionary. In addition to lodging, the woman created a pathway for the undocumented to restore their citizenship. While her service has provided an opportunity to rise above the inescapable cycle, the cost is $40 dollars (American). It often takes years — if not decades or a lifetime — to save that much money. And since the communities are nestled across a large swath of farmland, the missionary shared stories of people walking up to 18 miles to reach her office. The line is always out the door, and if the father of a household is the one to obtain the papers, he has to take a day off work.

Children at play in Bateye Don Juan

A long legacy of racial and political tensions between the two countries that divide the island of Hispaniola contributes to a national ambivalence toward the situation. Sugar is also one of the Dominican Republic’s most lucrative exports. One of the main buyers is Hershey, which is popular in countries like the United States. As consumers, it is our responsibility to be conscious of the supply chain behind the products we purchase: Ignorance should not be an excuse.

While inflammatory headlines such as Huffington Post’s “Thousands Woke Up At Risk Of Deportation In The Dominican Republic. Almost All Of Them Are Black,” help shed light upon the issue, they also run the risk of dehumanizing what’s occurring. International pressure has prompted the DR to reform policy in the past, but another way to help these people is to practice conscious consumerism. Choosing not to buy products that contain sugar from the Dominican Bateyes, for example,candy from The Hershey Company, demonstrates individual dissatisfaction with abusive work practices. I am grateful for my opportunity to have volunteered in the sugar cane communities and will never forget the people I worked alongside during that time.

SARAH SUTPHIN

Sarah is an undergraduate at Yale University and a content editor for CATALYST. As a traveler who has visited 30 countries (and counting!), she feels passionate about international development through sustainable mechanisms. Sarah has taken an interest in the intersection between public health and theater, and hopes to create a program that utilizes these disciplines for community empowerment. She is a fluent Spanish speaker with plans to take residence in Latin American after graduation.

Bridging the Inequality Gap for Panama’s Darién Province

Photo by Katie Chen on Unsplash

The Gallup-Healthways Global Well-Being Index has ranked residents of Panama as the leaders in “well-being” for two consecutive years. However, three weeks in communities of the Darién province exposed me to the destitution and gubernatorial neglect that blankets this eastern region. Inhabitants of the Darién have been stigmatized, leaving them without access to clean water, health care facilities, or economic opportunity. My experience led me not only to question the validity of the Index, but also to consider the ways we can empower a forgotten sub-population.

“A little further down the road, you’ll find that it comes to an end,” my local Panamanian guide remarked while en route to the compound where we reside for the following three weeks. At the time, the idea of a place with no road was beyond comprehension. How could people stay connected? How could they receive supplies? The answer to these questions is simple —they don’t.

Soon after arriving in Panama, I began to comprehend the “Darién Gap” which is a 99-mile swath of undeveloped swampland and forest located within Panama’s Darién province — a symbol of the many development projects that have been discontinued in the region over the past decades. I found that the double-edged sword of indigenous isolation offers cultural preservation on one side, clean water and healthcare deficiencies on the other.

The border between Panama and Colombia is the only one in the world that remains unpaved! While the decision to stop construction of the Pan-American Highway provided benefits to some groups, such as law enforcement officers against drug traffickers and indigenous inhabitants of the Gap who wish to preserve a traditional lifestyle, it also resulted in neglect of an entire region. With the fastest-growing economy in the Americas, Panama now has an opportunity to improve the quality of life for all of its citizens. Yet, despite the recent boom, the nation has the greatest economic inequality in the Americas with nearly 40 percent of the country living in poverty. Many of those who endure economic destitution live in the eastern half of the country, particularly in the Darién.

My three weeks in Panama were dedicated to community visits throughout this beleaguered province. We met with officials and members of individual households, and conducted surveys to determine the accessibility to fundamental necessities, such as clean water, health care, and education. I was an intern for a nonprofit based in Panama City, but which conducts most of its projects with American undergraduates serving communities of the Darién. This nonprofit creates partnerships with communities located in proximity to a road or a rocky pathway that Panamanian officials call highway. More indigenous groups are sheltered within the Darién Gap, undisturbed and unacknowledged.

According to community members who responded to our surveys in July 2014, lack of access to clean water is the main problem affecting daily life for an appreciable number of residents in the Darién province. Although the Panamanian government’s Ministry of Health is responsible for water distribution by means of aqueduct systems, complications such as project incompletion, water shortages, pipeline damages, and contamination from pesticides/animals inhibit achievement of the goal. Residents described complex, inconsistent, and seasonally based methods for receiving water. In the past, families might go two months without water when a government-constructed pipeline to a water tank is broken. When water finally arrives, it will sometimes come out dirty or contaminated from passage through farmland.

Photo by Aljoscha Laschgari on Unsplash

Observation and conversation with members of various communities taught me that collaboration between locals and external, resource-rich groups has been a driver for successful growth in this area. Yet, one person I met described the Darién province as “the temple of abandoned development projects” for the number of missionary and nonprofit groups that have attempted and failed to provide assistance to families in the greatest need. In an indigenous community named Emberá Puru, I noticed little blue water filters strewn about the property. The leaders explained that a missionary group had provided over 100 filters, but not explained how to use them. The group left after a week of what could be described as “voluntourism” — volunteering abroad that resembles a tourism opportunity — and the community was left with pieces of plastic polluting the land.

The neglected Darién province is not a unique case. Panamanians from other parts of the country (like Panama City) expressed surprise and/or distaste when my group revealed we were working in this eastern region. These people hold onto misconceptions, such as the idea that the Darién is filled with dangerous members of drug cartels or that it’s a completely unlivable swampland.

While the “Darién Gap” might lack a constructed road, the population of this area has done its best to overcome deficiency through resiliency. When a government or its people show indifference toward improving the lives of an entire population sector, outside measures need to be taken to reduce inequality. However, these outside measures should also be performed through culturally conscious and responsible mechanisms in order to achieve sustainable success. No clear-cut solution exists to resolve problems such as clean water, healthcare, and education inaccessibility in the Darién province, Panama. However, creative and collaborative efforts have the power to mediate substandard conditions and to catalyze change one household at a time.

SARAH SUTPHIN

Sarah is an undergraduate at Yale University and a content editor for CATALYST. As a traveler who has visited 30 countries (and counting!), she feels passionate about international development through sustainable mechanisms. Sarah has taken an interest in the intersection between public health and theater, and hopes to create a program that utilizes these disciplines for community empowerment. She is a fluent Spanish speaker with plans to take residence in Latin American after graduation.

MEXICO: Baja Smugglers

Daredevil outlaws. The Mexican drug war. All night trips on small fishing boats called "pangas" that smuggle migrant workers & marijuana into the United States. This is Baja Smugglers. A new documentary created by Jesse Aizenstat, author of Surfing the Middle East.