In the language of modern economics, the small island nation of Vanuatu in the South Pacific is labeled one of the world’s ‘least developed countries’. At the same time, Vanuatu has ranked number one on the pioneering Happy Planet Index. This incongruity points to major issues with today’s standard measures of human progress, and has many policymakers rethinking notions of wealth and how they shape development policy.

IMAGE COURTESY OF ORPHANAGES.NO

Orphanage Volunteering’s Shocking Link to Child Abuse

I never thought that playing catch with a kid could be a bad thing, or that goofing off could contribute to long-term psychological damage. Even now, as I write it, it all seems a little absurd. Is it really possible that making kids laugh could do permanent harm?

Every year, millions of people travel around the world to volunteer. Orphanages are one of the most popular destinations, and it makes sense. Many volunteers like working with children, often because children are enthusiastic and working with them is very active and “hands on.” Most of the tasks volunteers are given when working with kids are simple, and it is rare that volunteers are expected to have any specialized skills or to participate in any in-depth training before starting their volunteer work.

At the same time, orphanages are often understaffed and poorly kept up. Operating with limited resources (or under the appearance of limited resources), they are frequently on the lookout for people who are willing to pay to work. Placement companies and organizations provide orphanages with paying volunteers to help with childcare, teaching, cooking, and maintenance. Volunteers are told that they’ll be providing orphaned children with a more nurturing environment while orphanages get a steady income and a constant flow of helping hands.

All of this sounds fine and dandy, but the problem with orphanage volunteer work isn’t in the volunteer’s desire to help, but in the very existence and implementation of orphanages themselves.

Not many would-be volunteers realize that more than 80% of children who are labeled as “orphans” have a surviving parent. Even fewer understand that the traditional kinship structures of many non-western countries, especially those where orphanage volunteering is most common, actually result in very few children being left without someone to care for them (Richter and Norman, 2010; UNAIDS/UNICEF/USAID, 2004).

Which begs the question: why are there so many kids in orphanages?

There are orphans that need a home, and sometimes that means that they have to go into group care, but for many of the children who are labeled as orphans and blazoned across brochures, it’s poverty, not a loss of family, that put them there. Desperation will make people do unthinkable things, especially with the promise of ample food, a solid education, and a comfortable bed. Because of this, all around the world caregivers are willingly giving up their children to orphanages. Sometimes, they even get cash in return. This isn’t altruism on the orphanages part, it’s well-disguised human trafficking.

None of this is the volunteer’s fault, but just by working at orphanages, volunteers are contributing to the problem and, inadvertently, may be supporting the exploitation and traumatization of children - the opposite of what their goal was in going to volunteer in the first place.

Once the volunteer arrives at the orphanage, they might get a feeling that something is off, but it’s easy to push that feeling away when there are kids who genuinely do need help regardless of how they got there. The do need attention and love, they do need teachers and caregivers, and when they get those things children, especially young children, are often overwhelming grateful. It’s hard to walk away, and it’s easy to ignore the problems when there’s a kid on your lap, a kid on your back, and another looking for a place to grab onto.

While the industry is definitely shockingly corrupt, there are many orphanages and children’s homes that truly believe that they are acting in their ward’s best interests and are committed to putting the child’s, not the paying visitor’s, needs first. The way children get into an orphanage, and the ongoing exploitation of them once they have arrived, are part of a systemic problem that may not apply to every orphanage. However, there are also more personal impacts of short-term volunteering, relevant across the entire industry, that may be just as harmful.

Three key aspects of child development that most people can agree on are:

- Children benefit from long-term relationships with adult figures.

- Those adults don’t have to be a family member in the traditional sense, but having a stable familial atmosphere promotes positive development.

- Children without stable relationships with adults often suffer from psychological and behavioral issues that are directly related to a lack of stability and guidance early in life.

All three of these are proven concepts that apply around the world from Cambodian orphanages to the American foster care system. Orphanages that rely heavily on free or paying volunteer labor and, as a result, tend to have only a small local staff, act in complete disregard of these three concepts. They drastically reduce the opportunities that their children have to form long-term relationships, they create an unstable environment where people are constantly rotating in and out and, by doing those two things, they are causing psychological damage to the children that they are supposed to be helping.

As a privileged “gringa,” or white girl, who spends time in impoverished communities, I’ve come to realized not only what my presence can mean, but also what it can do. I know that when I was doing short-term volunteer work, I was as much of an exotic distraction to the children I was working with as they were to me. Even when they had the opportunity to form relationships with locals who could serve as role models, it was my presence that was highlighted. I, the person who was going to leave in just a few days, was given all the attention that should have been shined on the heroes who the children were interacting with every day.

Some might argue that this is giving volunteers too much credit since that all they are there to do is help. Any person who has had children climb on top of them in a frenzy for attention, clamor to have their picture taken, or cry in their arms as they prepare to leave, has to admit that they are in a position of immense power. By choosing to support orphanages that rely on volunteer labor, well-meaning volunteers are inadvertently using this power to exacerbate a broken system and disincentivize governments and NGOs from finding lasting systems-based solutions.

Even if the orphanage that you’ve been eyeing looks perfect, short-term volunteering at orphanages feeds a market that trafficks in, exploits, abuses, and permanently traumatizes the very children that you are looking to help. Even in the best of cases, short-term volunteer work, especially unskilled and non-specialized placements, encourage an uneven power dynamic in which the volunteers are held above the locals. They are looked to as benevolent angels, turning the lens away from the men and women who could serve as positive adult role-models for children who desperately need a stable family environment.

I’ve would never have labeled myself as abusive before I volunteered at an orphanage, and I think it’s fair to say that most volunteers would recoil at the suggestion that they could be categorized as abusers. Now that I know what orphanage volunteer does to children, I have to call it out for what it is - abusive and exploitative.

So no, you shouldn’t go. Don’t support orphanage volunteering. Don’t support child abuse.

You can support this effort in two ways:

- Sign the petition calling on travel operators to remove orphanage volunteering placements from their websites.

- Share this post, along with your thoughts on orphanage volunteering, using the hashtag #StopOrphanTrips.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON HUFFINGTON POST.

PIPPA BIDDLE

Pippa Biddle is a writer. Her work has been published by The New York Times online, Antillean Media Group, The FBomb, MTV, Elite Daily, Go Overseas, Matador Network, and more. She is a graduate of Columbia University with a degree in Creative Writing. Twitter: @PhilippaBiddle

VIDEO: A Fisherman's Freedom in Madagascar

Ravelo was trapped; He couldn't afford to continue paying the local loan shark to rent fishing equipment, because he couldn't catch fish to sell and make his payments. He couldn't catch fish because the mangrove estuaries had been depleted of wood for fire, in turn decimating the population of fish and seafood.

When Ravelo was hired by Eden Reforestation Projects, he was not only able to make an income planting trees, but his environment began to revitalize.

Eden Reforestation Projects hired Outskirt Films to tell this story on the remote coast of Madagascar. This powerful story was filmed in Madagascar by Outskirt Films.

VIDEO: Who's Developing Who?

The common assumption is that the rich countries of the global north, through foreign aid programs and by participating in projects like the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals), are helping the less wealthy countries of the global south develop. But how true is this?

Right now, for every $1 that is given in foreign aid to the global south, around $18 is taken out by other means, most notably rigged trade deals than benefit the most powerful countries and corporations, debt repayment on debts already paid off many times over, and massive tax evasion and other forms of corruption, committed by political and business elites north and south, and facilitated by the large and growing web of tax havens. So in the grand scheme of things, who’s actually developing who?

The answer to this question will also affect your opinion of the SDGs. They don’t have a lot to say about this dynamic, and in fact riff pretty heavily on the basic idea that it’s the north that is the generous party. They do acknowledge both the vast level of illicit finance, and that the global financial system is relevant to their project, but capture their level of concern in vague statements about the need to “enhance global macroeconomic stability” through “policy coordination”. There are no specific responsibilities for anyone, or any actual targets.

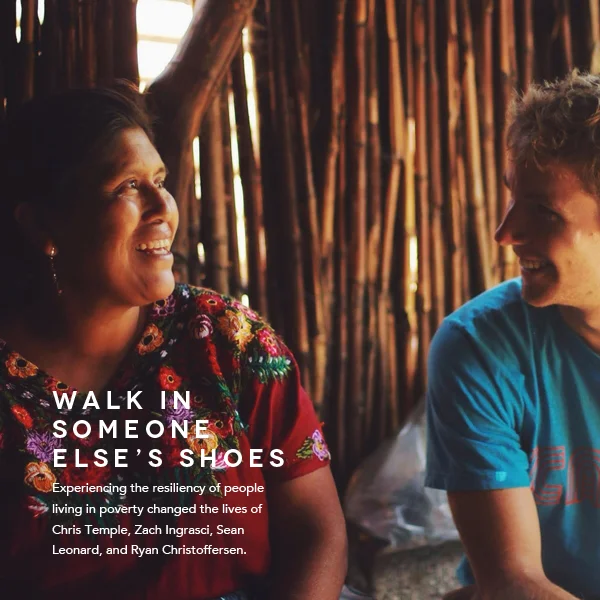

Photo credit: Living On One

Living on One Dollar: Four Students Fight Against Global Poverty

Sometimes all we need is to get away and gain a bit of perspective, whether it is to your old tree house in your back yard, your favorite coffee nook downtown, or a completely different country. Taking a moment to recognize the elements of life and how blessed you are can bring infectious happiness and gratitude, so share this pleasure by immersing yourself in the lives of others and trying to see the world from their point of view. That’s what four students from Claremont McKenna College did - they traveled to Pena Blanca, Guatemala to get a true perspective of extreme poverty and engage with the people living in this village who struggle to survive on $1 per day. Experiencing the resiliency of people living in poverty changed the lives of Chris Temple, Zach Ingrasci, Sean Leonard and Ryan Christoffersen by grounding them from our materialistic, over-consuming reality and allowing them to learn about the everyday hardships that people must face simply just to survive another day. Now, these four men hope to change the lives of the 1.1 billion impoverished people who live on $1 a day by raising awareness, fostering inspiration and encouraging action.

Chris and Zach were kind enough to answer a few questions about the process that led to the creation of their newly released documentary ‘Into Poverty: Living On One Dollar’, which details their travels to Pena Blanca, their experiences of living on $1 per day for eight weeks, the issue of global poverty and how you can help.

Q | How did you come up with the idea for the trip and actually make it a reality?

We were studying economics and international development in school, but the issues we were reading about seemed so far from our daily reality. We constantly heard the overwhelming statistic that 1.1 billion people live under $1 a day, but growing up in Connecticut and Seattle, had little ability to understand the reality of life at that level. So we came up with the concept to live under $1 a day for two months ourselves. We knew that we'd never be able to truly replicate poverty but we did believe that this would be a valuable experience.

Having an idea and making it a reality are two very different things. We developed the idea over a 10 month period and applied for funding from 9 different sources but got rejected from all of them. We had no track record of making films and the project was different and potentially dangerous – making it difficult for someone to fund. Finally about a month before leaving, we got $4,000 from the Whole Planet Foundation, which was enough for our plane tickets and $1 a day each while there. Actually going was a difficult decision to make though. My family wasn’t particularly supportive and there was a lot of pressure to get a traditional internship with a consulting firm or investment bank.

Q | How did you prepare yourselves for a trip that is so different from the reality that you are used to?

Looking back, we were horribly unprepared for the trip, both physically and emotionally. But I’m not sure how we could prepare for what the following few months were going to bring. It may have been to our advantage that we didn’t have much time to think about the trip right before going because we were so busy with end of the year exams at school.

Photo credit: Living On One

Q | Why did you choose Pena Blanca for this experience?

We chose Guatemala because I (Chris) had been lucky enough to travel there a few years before and had fallen in love with the culture and people, especially the rural areas. When we thought of the idea for the documentary, we were studying economics in school, and were shocked to learn that in Guatemala almost 50% of the population lives in poverty and in rural areas 75% of the indigenous population lives in poverty. This was representative of rural poverty in many parts of the world, and an unimaginable problem that we wanted to learn more about.

We chose Pena Blanca specifically because we knew people at a nearby non-profit who had been to the community before, knew the average income, and knew that it was a safe community.

Q | At any point in the trip did you want to give up? How did you persevere through the tough times?

I (Zach) remember one morning when I woke up on our dirt floor after being bitten by fleas all night. I didn't know if we were going to have enough money for food that day let alone medicine for a parasite that Chris had just contracted from contaminated drinking water.

The discomfort of the dirt floor and fleas was definitely challenging but it was the stress of having a small, irregular income and not knowing what illness or disaster was going to hit us next that was really the hardest part.

These challenges made us realize just how innovative and strong the poor have to be to even survive. Seeing our neighbors strive to improve their lives, in the face of such hardship, inspired us to stay the 56 days and do everything we can to give back. We really built life-long friendships with them – friendships that transcend just this film – which is the most rewarding part. They inspired us to create this film that would inspire action through hope, not through guilt.

Q | Did you ever feel guilty knowing that you would return home in a few weeks to electricity, running water, an actual bed, etc.? How did you deal with those feelings?

The hardest part about the whole trip was leaving and knowing that our neighbors faced an unpredictable and extremely challenging future. I think a lot of people feel this sense of guilt when they come back from abroad, and they hide from those feelings instead of facing them. It seems like such a shame that we travel and build these amazing relationships and then never follow up again or keep in touch. What has been so lucky about this project is that we’ve been able to go back 3 times to Pena Blanca over the past few years and speak monthly on the phone with Chino, Anthony and Rosa. We’re even friends with Rosa on Facebook!

Technology allows us to stay connected around the world and continue to learn from one another and be there for one another in times of need.

Q | What is your advice for other college students who want to go on a service trip or get active about a topic they are passionate about?

I would encourage everybody to walk in somebody else’s shoes, if only for a few days. Through the experience, you’ll gain empathy for someone else’s reality and never judge, disregard, or ignore a person like them in the future. For me (Chris), I will never see a hotel janitor in the same light. Anthony, one of our neighbors, was one of the most generous and intelligent people I’ve ever met, yet he cleaned hotel rooms for a living. This might not be considered the most accomplished job to some, but his formal job and steady paycheck were the envy of the entire town.

There are so many ways for someone to make a difference in the world. It doesn’t have to be an international service trip, it could be mentoring a low-income student nearby or an environmental project. What’s important is that you give something, your time, your money, or your skills. These actions will help you find your inspiration and lead you down a path you would have never expected. I was going to intern for an investment bank for the summer, but instead went to Guatemala, and my whole life path was changed.

Photo credit: Sean Leonard

Q | Overall, what have you learned from these experiences and how have they changed your life and outlook?

If there’s one thing I walked away with from Guatemala, it’s that small things can have a huge effect on the lives of the extreme poor. By understanding this, we can feel empowered that change is possible.

For billions of the poor it is not a choice to live with less. What is most troubling is not that they live with less material things but that they live with less opportunity to improve their lives. They often don't have access to things we take advantage of everyday like education, financial services, nutrition, healthcare and even access to clean water. For those who have these resources it is our responsibility to join together and make a difference in the world.

One of our closest friends in Peña Blanca is Rosa, a 21-year-old woman, who has this dream of becoming a nurse. Sadly, in the 6th grade, she was forced to drop out of school because her father got sick. Years later, with the help of a microfinance loan of only $200, she was able to start her own weaving business and with the profits, begin paying for herself to go back to school and keep her dream alive. Rosa is one of the smartest, most motivated people we have ever met, all that she lacked was an opportunity to improve her own life.

Learn, Connect, Act.

Learn more about Living On One

Connect via Facebook and Twitter

1. Spread the word. Our film just released for anyone to download it on our website or iTunes.

2. Give a Donation. You can support education, clean water, or microfinance for the community of Pena Blanca by giving to one of our impact partners here: www.LivingonOne.org/changeseries

3. Buy Shirts or Sandals. Our shirts are handmade by the star of our film, Rosa, and help pay for her education. The sandals support the health and education of Guatemalan children like Chino.

4. Contact High School teachers and tell them to show the film and/or bring us to speak so we can create a generation of active global citizens.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN CONSCIOUS MAGAZINE

CARLY LONG

Carly Long is a contributing writer and researcher for various publications, including Conscious Magazine. Her articles have focused on companies that incorporate social good, as well as individuals who work to improve the lives of others. Carly is also a self-taught painter, as she developed an original technique of custom painted photographs.

VIDEO: Can You Live on Just £1 a Day?

Can you live off just £1 a day? For millions of people around the world, this is a reality. These people lived on £1 per day for five days and shifted below the poverty line. Shift UK was created to stand with those who live like that every day and raise money to support life-changing projects.