A group of friends started a journey to Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Uruguay, Paraguay and Southern Brazil in their old and rusty Land Rover. They encountered lots of winds, emptiness, pampas, bustling cities, animals, deserts and waterfalls—all wrapped up in just under 6 minutes. Enjoy the ride!

Peace and Stability in Uruguay

The second smallest country in South America, Uruguay is one of the most stable and prosperous countries in all of Latin America.

Montevideo, Uruguay. Gustavo. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

South America’s Uruguay has been one of the most stable countries in the world for years. It’s the second smallest country in South America, and despite not having many natural resources, they have still had a lot of economic growth and prosperity. Uruguay has in general been a symbol of peace and social inclusion, despite its small population. Their social attitudes are extremely progressive and lenient, especially towards things like legalizing marijuana and same-sex relationships and marriages. Many countries in Latin America suffer from violence, corruption and oppression, but Uruguay has grown in its economic, political and social spheres. Their policies towards immigration are also relatively open, and the people tend to welcome foreigners who want to move to the country. They have the largest sized middle class, proportionally, within Latin America and have been called the “Switzerland of Latin America” due to their economy, size, and industrial, trade, and service sectors. Uruguay has one of the highest GDP per capita in the region, and the income distribution is very equal. The World Economic Forum claims Uruguay is the most equitable country in the world.

Uruguay’s main exports are agricultural products, such as corn, rice soybeans and wheat, as well as meat products, especially dairy. They love meat, especially beef, and their national dish is asado, which is literally just barbecued meat. Interestingly enough, pasta is another widely consumed food due to the arrival of Italian immigrants that came during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Though Uruguay’s pasta has Italian inspiration, Urguay has its own spin on a widely-loved cuisine. In terms of beverages, yerba mate is one of their favorites, a tea-like drink that has become a respected cultural aspect for the people. There was a military regime in the 1970s that strongly discouraged public gatherings, and so people would get together to drink yerba mate and socialize. This tradition has carried on even today and people now love to gather, drink it, and talk.

Their tourism industry is another factor that has increased their economic growth. People love Montevideo, the capital, and say that it is has the highest quality of life out of all the cities in South America. Punta del Este is an extremely popular beach resort that doubles as a college town that also adds to their tourism industry. It helps that the country is relatively safe, ranking 32nd on the 2020 Peace Index, compared to the United States’ 121st. Because of this, the country has had a solid 15 years of positive economic growth, and their poverty rate decreased by 22% from 1999-2019. In addition, their literacy rate is extremely high, the highest in all of Latin America, and both education and healthcare are free and accessible to everyone.The government is very transparent, considered the least corrupt government in Latin America and the 23rd least corrupt government in the world. Their political stability in the Global Economy was rated as 1.05 in 2020 (the scale is from -2.5 – 2.5) and they have had an overall upward trend since 1996. The United States, in comparison, was rated -0.02 in 2020, with a major downward trend since 1996.

Shot of Montevideo. Gustavo. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Despite all this, Uruguay’s rise in prosperity hasn’t always been the most stable. The rate at which their poverty levels is decreasing also slowed down and stagnated a bit in the past few years, and, like most countries, Uruguay suffered from the pandemic. The poverty rate increased by 2.8% the first year of the pandemic, even through Uruguay’s preexisting social protection systems and the new measure they introduced in response to the virus. In 2021, however, the economy recovered a little and the poverty fell from 11.6% to 10.6%.

The country as a whole, though, did not have to make many changes in order to adjust to virtual life. Since they place such a high value on education and technology, they were able to easily use online platforms, and their universal health care allowed them to take preventative measures at a lower cost than other countries. All this combined allowed Uruguay to slowly reopen their schools earlier and faster than other countries in the region. Like many countries in the world, their poverty rates, though low, are disproportionate in areas such as race, sex and religion , but they do have a strong commitment and desire to strengthen the country and create policies to overcome these factors.

Katherine Lim

Katherine is an undergraduate student at Vassar College studying English literature and Italian. She loves both reading and writing, and she hopes to pursue both in the future. With a passion for travel and nature, she wants to experience more of the world and everything it has to offer.

International Human Rights Court Rules in Favor of Trans Rights

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled that the government of Honduras was responsible for the 2009 murder of a transgender woman. Today, Honduras is one of the largest contributors to anti-trans violence in Latin America.

Transgender pride flags. Ted Eytan. CC BY-SA 2.0

On June 26, the Costa Rica-based Inter-American Court of Human Rights delivered a landmark ruling in a transgender rights case. The court held that the government of Honduras was responsible for the 2009 murder of trans woman and trans rights activist Vicky Hernández, stating that the government had violated Hernández’s rights to life and fair trial.

Hernández was 26 years old when she was killed by a single gunshot to the head. No one was ever charged for the crime.

The Court’s ruling stated that Honduran authorities did not sufficiently investigate Hernández’s death. Her murder was dismissed quickly as a “crime of passion,” and police failed to interview anyone from the scene or examine the bullet casing. It is unclear whether a postmortem examination was performed.

Lawyers acting on behalf of Cattrachas, the LGBTQ+ rights organization that brought forward the case, argued that this incomplete investigation was a result of Hernández’s gender identity. Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights reports that during the investigation, authorities continuously identified Hernández as male and referred to her on documents and records by her birth name, which she did not use. In 2009, shortly before Hernández’s killing, Human Rights Watch published a report which found that police in Honduras routinely failed to investigate reports filed by trans people. The report also detailed the harassment and beatings that trans people had endured at the hands of the police.

Hernández’s murder occurred on June 28, 2009, the first night of a military coup against then-President Manuel Zelaya. Zelaya was taken into custody, and the military imposed a 48-hour curfew, leaving the streets closed to everyone but military and police forces. Hernández was a sex worker, and was still on the street after curfew arrived, along with two other trans women. The three women saw a police car approaching and scattered, fearing violence. The next morning, Hernández’s body was found in the street.

Due to the circumstances surrounding her death, lawyers for Hernández’s case posited that she was the victim of an extrajudicial killing, meaning that state agents were responsible for her death. Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights points to the execution-style way in which Hernández was shot and the fact that the streets were closed to everyone but police and military forces, as well as the lack of effort put into the criminal investigation.

In its ruling, the Court found evidence that state agents had participated in Hernández’s death.

Hernández’s murder was the first in a wave of anti-trans violence that followed the 2009 coup. Cattrachas documented 20 deaths of LGBTQ+ people in the 15 years before the coup, and 31 deaths in the eight months directly afterward. 15 of these 31 people were trans women, like Hernández.

Today, Latin America is still a deadly area for LGBTQ+ people. Research released in 2019 showed that four LGBTQ+ people are murdered every day in Latin America and the Caribbean, with Honduras, Columbia and Mexico accounting for nearly 90 percent of these deaths. In 2020, Human Rights Watch published a follow-up to their 2009 report, which found that LGBTQ+ Hondurans still face rampant discrimination and violence from police and other authorities, as well as from non-state actors.

Twelve years after Hernández’s murder, Honduras is finally being held accountable for its anti-LGBTQ+ violence and being made to implement reforms. Activists hope that the ruling will encourage other Latin American countries to address their own issues with violence against the LGBTQ+ community.

The Court’s ruling included orders for the Honduran government to pay reparations to Hernández’s family, restart its investigation into her murder and publicly acknowledge its own role in the event, train security forces on cases involving LGBTQ+ violence, and keep a better record of cases motivated by anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment. The Court also ordered the Honduran government to allow people to change their gender identity in documents and public records, which is a major step forward. The next step is ensuring that Honduras’ new LGBTQ+ legislation is actually enforced.

Rachel Lynch

Rachel is a student at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY currently taking a semester off. She plans to study Writing and Child Development. Rachel loves to travel and is inspired by the places she’s been and everywhere she wants to go. She hopes to educate people on social justice issues and the history and culture of travel destinations through her writing.

A military coronavirus relief worker in Venezuela. modovisible // pixabay.

Venezuela Labels Coronavirus-Infected Citizens as ‘Bioterrorists’

Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro has implemented harsh measures throughout the COVID-19 pandemic to arrest, detain and punish those infected with the virus and citizens who have broken quarantine measures. These authoritarian measures mark a stark contrast with the relief efforts of neighboring countries, as Maduro has labeled those suspected of coming in contact with the virus as “bioterrorists.”

The government was initially quick to respond to the virus, suspending all flights from Europe and Colombia and banning all public gatherings on March 12, before the country had officially reported any cases. However, cases in Venezuela have since risen, with experts suggesting that the current tally of 42,898 infections is much lower than the actual case number due to an insufficient amount of testing materials.

Infected Venezuelan citizens have been subjected to inhumane treatment, leading many to defy the government’s orders. According to a taxi driver from Caracas who was forced into a state-run isolation facility, the government treats infected citizens in an inhumane manner.

“I spent three days sleeping on an aluminum chair,” the driver said in an interview with Bloomberg. “They fed us cold rice, lentils and arepas. The place was controlled by armed militias and Cuban doctors.”

Venezuela’s approach to the pandemic is a result of its failing health care system and Maduro’s resistance to internal reforms advocated for by activists over the past decade. The country’s sociopolitical system, which at one time was hailed by some as one of Latin America’s best, was brought to its knees after oil prices plummeted in the early 2010s. This just exacerbated shortages of basic food staples that began under the presidency of Hugo Chavez.

Using drastic anti-protest tactics which became commonplace in the mid-2010s, Maduro has authorized security forces to impose punishments for violating social distancing protocol such as sitting under the hot sun for hours, intense physical exercise and beatings.

In response to citizens evading testing facilities for fear of being subjected to harsh punishments, the Venezuelan military has encouraged citizens to turn in neighbors who they suspect have come into contact with the virus throughout the summer.

“Defense for the health of your family and community,” one tweet by the military stated in Spanish. “[Someone who helps others hide their infections] is a bioterrorist, which puts everyone’s health at risk. Send [us] an email with their information and exact location. #ReportABioterrorist.”

Maduro has largely ignored calls to reform his response to the pandemic, dismissing claims that those infected have been treated inhumanely.

“[In Venezuela] you’re given care that’s unique in the world, humane care, loving, Christian,” Maduro said in an Aug. 14 national address.

In response to calls for aid from organized opposition groups, on Aug. 21 the United States granted activists access to millions of dollars of previously frozen Venezuelan assets to be used to support health care workers. However, it is unclear how these funds will be accessed by opposition-supported health care workers, or if the Venezuelan government will be able to interfere with their distribution.

As of this article’s publication, Maduro has not responded to calls for pandemic relief reform, nor have efforts been made to test in a more humane manner.

Jacob Sutherland

is a recent graduate from the University of California San Diego where he majored in Political Science and minored in Spanish Language Studies. He previously served as the News Editor for The UCSD Guardian, and hopes to shed light on social justice issues in his work.

Fight for Civil Liberties Doesn't Stop for a Pandemic in Chile

Despite unrest in Chile, feminist group Las Tesis continues to advocate for justice against police brutality and sexual violence toward women in Latin America.

Translation: “Systemic violence is the worst crime.” John Englart. CC BY-SA 2.0

Last year, Chilean feminist group Las Tesis released “Un Violador en Tu Camino” (“A Rapist in Your Path”), a song that became an anthem against sexual violence worldwide. The piece, which calls out the judicial system and the struggle of women across Latin America, has been performed all around the world in the form of flash mobs. Many who participate wear black blindfolds and green scarves to advocate for legal abortion practices as well.

The song first was created in light of the social inequality protests occurring in Chile in November 2019. The lyrics call out the unfair treatment of the Chilean government toward women. It says that a narrative is being written where women are to blame for sexual violence. Yet, the song places blame on the patriarchy, police and government systems for being blind to this ongoing violence.

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Chile is considered one of the world’s most unequal countries and is susceptible to climate change. Chile is also considered to have one of the highest costs of living across South America. While the rich prosper from their investments in terms of development, the poor communities and Indigenous people suffer at the hands of urbanization.

Feminist sign in Chile which translates to “the feminist struggle is also against neoliberalism.” John Englart. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Many Chileans consider themselves “at war against a powerful enemy.” Rather than succumbing to the protesters’ demands, President Pinera declared a state of emergency that involved the deployment of the military to control crowds and the institution of a curfew. These measures have caused a sharp decline in protests like Las Tesis’.

International attention has focused on the treatment of protesters, with allegations of human rights violations. For instance, there have been claims that protesters may have been tortured, resulting in at least 19 deaths and 20 people being reported missing. Additionally, there has been a 15% increase in sexual violence reports since last year.

However, on June 12, the police filed a lawsuit against Las Tesis. In the lawsuit, police claim that the feminist group encourages violence against officers of Chile’s national police force, Carabineros de Chile. Charges came after the release of “Manifesto Against Police Violence,” a video produced alongside Russia’s Pussy Riot where protesters stood outside of a police station and demanded to “fire the police.” Chilean police took the video as threats against officers, but no papers have been officially served yet to the feminist group.

Daffne Valdes, one of the founders of Las Tesis, said in an interview with Al-Jazeera that “this is an attack on freedom of expression,” calling it a form of censorship. Even though in both the song and video by Las Tesis the police are called out as “rapists,” group members say they are simply referring to the corruption seen throughout Chile’s police system.

Eva Ashbaugh

is a Political Science and Gender, Sexuality, and Women's Studies double major at the University of Pittsburgh. As a political science major concentrating on International Relations, she is passionate about human rights, foreign policy, and fighting for equality. She hopes to one day travel and help educate people to make the world a better place.

A female-dominated protest moving to "Un Violador en Tu Camino" (“A Rapist in Your Path”). Wotancito. CC BY-SA 4.0

The Chilean Roots of a Global Anti-Gender-Based Violence Movement

On the 2019 International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, over 10,000 women gathered outside Chile’s Santiago National Stadium, a former detention and torture center from Chile’s military dictatorship. “Patriarchy is our judge/That imprisons us at birth/And our punishment/Is the violence you DON’T see” the group chanted, their clothes and bodies marked with anti-violence slogans. “It's femicide!” they shouted into the frigid air. “It's not my fault, not where I was, not how I dressed!” They placed their hands behind their heads, then squatted up and down, mimicking the movements that Chilean police officials and prison wardens force females to perform while naked.

This is the movement that has globally spread, dismantling the structural forms of gender violence set in place by police and judiciary systems. The protests feature the Chilean song “Un Violador en Tu Camino,” or “A Rapist in Your Path.” Created by the Valparaíso feminist collective Las Tesis, it challenges the gender violence so prominently institutionalized by political structures. Las Tesis works closely with various activists and scholars to demystify rape as an act of pleasure. Specifically, “Un Violador en Tu Camino” is based on the work of Argentine-Brazilian anthropologist Rita Segato, one of Latin America’s most celebrated anthropologists of gender violence. Las Tesis also investigates the sexual violence, homicide and rapes within Chile that are left unaddressed in the criminal justice system.

The song was first publicly performed in front of a Valparaíso police station. As the initial protest, women merely sought to impose small-scale street interventions. However, as the visceral lyrics moved through global media, they inspired similar demonstrations throughout Latin America and beyond.

Thousands of women performed the piece at the Zócalo, Mexico City’s main square, on November 29, 2019, roughly a week after the Valparaíso protest. Since then, Las Tesis’ song has spurred movements in Latin American countries such as Colombia, Venezuela, Peru and Argentina, and has even spread to global protests in London, Berlin, Paris, Madrid, Barcelona, Tel Aviv, New Delhi, Tokyo, Beirut, Istanbul and New York City.

Each protest site transforms the musical base, adapting the movements and song to their national identity. Within Latin America, green scarves represent the campaign for legal abortion. Black blindfolds acknowledge the ways that women are made vulnerable by Chilean police. Brazilian activists add the lyrics, “Marielle is present. Her killer is a friend of our president.” They reference Marielle Franco, an assassinated city council member from Rio de Janeiro. An ongoing investigation will determine if Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro was involved in her killing.

“It’s the cops. It’s the judges. It’s the system. It’s the president. The rapist is you.” This phrase has been chanted around the world, demanding rectification for years of human rights violations. As female protesters gather in urban areas and repeat these words, they point— physically and metaphorically—to the courthouses, police headquarters, and presidential palaces that have systematically dehumanized women, promoting gender violence and oppression. Media, movement and song give women the platform to insert their collective power and instill political change.

Anna Wood

is an Anthropology major and Global Health/Spanish double minor at Middlebury College. As an anthropology major with a focus in public health, she studies the intersection of health and sociocultural elements. She is also passionate about food systems and endurance sports.

Rio

A year ago, Yury Sharov was asked to go to Rio with a couple of musicians from London to make a music video for their song, capturing their holidays on the IPanema beach. After the video was done, Yury had a lot of material that was not used and decided to make this short video about all the sides of Rio.

Black women in Brazil protest presidential frontrunner Jair Bolsonaro, who is known for his disparaging remarks about women, on Sept. 29, 2018. AP Photo/Silvia Izquierdo

Sexism, Racism Drive More Black Women to Run for Office in Both Brazil and US

Motivated in part by President Donald Trump’s disparaging remarks about women and the numerous claims that he committed sexual assault, American women are running for state and national office in historic numbers. At least 255 women are on the ballot as major party congressional candidates in the November general election.

The surge includes a record number of women of color, many of whom say their candidacies reflect a personal concern about America’s increasingly hostile, even violent, racial dynamics. In addition to the 59 black female congressional candidates, Georgia’s Stacey Abrams hopes to become her state’s first black governor.

The U.S. is not the only place where the advance of racism and misogyny in politics has has spurred black women to run for office at unprecedented levels.

In Brazil, a record 1,237 black women will be on the ballot this Sunday in the country’s Oct. 7 general election.

Brazilian women rise up

I’m a scholar of black feminism in the Americas, so I have been closely watching Brazil’s 2018 campaign season – which has been marked by controversy around race and gender – for parallels with the United States.

Last weekend, hundreds of thousands of Brazilian women marched nationwide against the far-right presidential frontrunner Jair Bolsonaro, under the banner of #EleNao – #NotHim.

Bolsonaro, a pro-gun, anti-abortion congressman with strong evangelical backing, once told a fellow congressional representative that she “didn’t deserve to be raped” because she was “terrible and ugly.”

Bolsonaro has seen a boost in the polls since he was stabbed at a campaign rally on Sept. 8 in a politically motivated attack.

Protests in Rio de Janeiro against Jair Bolsonaro on Sept. 29, organized under the hashtag #EleNao (#NotHim). AP Photo/Silvia Izquierdo

Brazil has shifted rightward since 2016, when the left-leaning female president Dilma Rousseff was ousted in a partisan impeachment process that many progressives regard as a political coup.

Her successor, then-Vice President Michel Temer, quickly passed an austerity budget that reversed many progressive policies enacted under Rousseff and her predecessor, Workers Party founder Luís Inácio “Lula” da Silva.

The move decimated funding for agencies and laws that protect women, people of color and the very poor.

Racism in Brazil

In Brazil, these three categories – women, people of color and the very poor – tend to overlap.

Brazil, which has more people of African descent than most African nations, was the largest slaveholding society in the Americas. Over 4 million enslaved Africans were forcibly taken to the country between 1530 and 1888.

Brazil’s political, social and economic dynamics still reflect this history.

Though Brazil has long considered itself colorblind, black and indigenous Brazilians are poorer than their white compatriots. Black women also experience sexual violence at much higher rates than white women – a centuries-old abuse of power that dates back to slavery.

Afro-Brazilians – who make up just over half of Brazil’s 200 million people, according to the 2010 census – are also underrepresented in Brazilian politics, though sources disagree on exactly how few black Brazilians hold public office.

Three Afro-Brazilians serve in the Senate, including one woman. In the 513-member lower Chamber of Deputies, about 20 percent identify as black or brown. Women of color hold around 1 percent of seats in the Chamber of Deputies.

Black women step into the fray

That could change on Sunday.

This year, 9,204 of the 27,208 people running for office across Brazil are women, which reflects a law requiring political parties to nominate at least 30 percent women. About 13 percent of female candidates in 2018 are Afro-Brazilian.

A campaign ad for Rio city council member Talíria Petrone, who is running for Congress.Facebook

In most Brazilian states, that’s a marked increase over Brazil’s last general election, in 2014, according to the online publication Congresso em Foco.

In São Paulo, Brazil’s most populous state, 105 black women ran for office in 2014. This year, 166 are. In Bahia state, there are 106 black female candidates for political office, versus 59 in 2014. The number has likewise doubled in Minas Gerais, from 51 in 2014 to 105 this year.

As in the United States, Brazil’s black wave may be a direct response to alarming social trends, including sharp rises in gang violence and police brutality, both of which disproportionately affect black communities.

But many female candidates in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil’s second largest city, say one specific event inspired them to run.

In March, Marielle Franco, an Afro-Brazilian human rights activist and Rio de Janeiro city councilwoman, was assassinated – the 11th Brazilian activist to be murdered since November 2017.

Franco’s murder remains unsolved, but she was an outspoken critic of the military occupation of Rio’s poor, mostly black favela neighborhoods. The ongoing police investigation has implicated government agents in the shooting, which also killed her driver.

Her death unleashed an avalanche of activism among black women in Rio de Janeiro, with new groups offering fundraising and political training for female candidates of color.

On Sunday, 231 black women from Rio de Janeiro state will stand for election in local, state and federal races – more than any other state in Brazil and more than double the number who ran in 2014.

Black representation from Rio to Atlanta

Black women may have been historically excluded from Brazil’s formal political arena, but they have been a driving force for social and political change since the country’s transition from dictatorship to democracy in 1985.

Decades before #MeToo, Brazilian women of color were on the front lines of activism around issues like gender-based violence, sexual harassment and abortion.

The March 2018 assassination of Rio de Janeiro city councilwoman, Marielle Franco, spurred a wave of black women running for local and federal office in Brazil. Reuters/Ricardo Moraes

Brazil has hundreds of black women’s groups. Some, including Geledes, a center for public policy, are mainstays of the Brazilian human rights movement. The founder of the Rio de Janeiro anti-racism group Criola, Jurema Werneck, is now the director of Amnesty International in Brazil.

The fact that thousands of black women, both veteran activists and political newcomers, will appear on the ballot on Sunday is testament to their efforts.

As in the United States, black Brazilian women’s demand for political representation is deeply personal. They have watched as their mostly male and conservative-dominated congresses chipped away at hard-won protections for women and people of color in recent years, exposing the fragility of previous decades’ progress on race and gender.

Black women in Brazil and the U.S. know that full democracy hinges on full participation. By entering into politics, they hope to foster more inclusive and equitable societies for all.

KIA LILLY CALDWELL is a Professor of African, African American, and Diaspora Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Through the “Open Veins of Latin America” | Bogota to Lima by Bicycle

Photo essay by photographer Bernardo Salce, who rode 4,000 km on his bicycle from Bogota, Colombia to Lima, Peru

Read MoreWAVES For Development: Changing Lives in Peru Through Surf

Meet Dave Aabo, the founder of WAVES for Development, a volunteer surf organization operating in Peru and around the world, in this exclusive CATALYST interview.

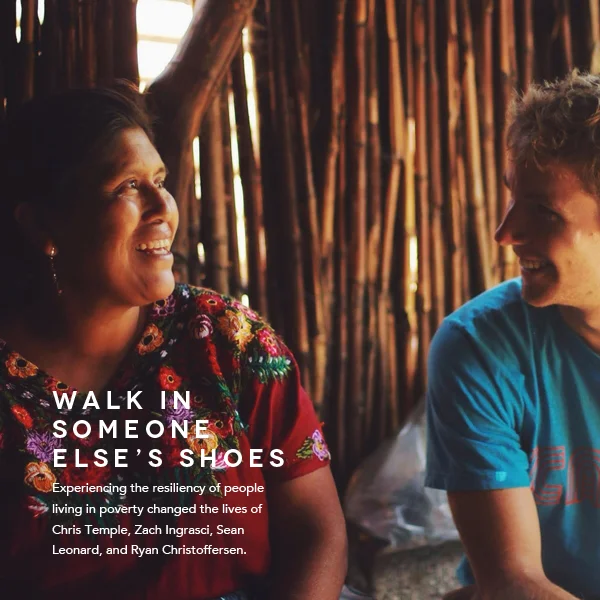

Read MorePhoto credit: Living On One

Living on One Dollar: Four Students Fight Against Global Poverty

Sometimes all we need is to get away and gain a bit of perspective, whether it is to your old tree house in your back yard, your favorite coffee nook downtown, or a completely different country. Taking a moment to recognize the elements of life and how blessed you are can bring infectious happiness and gratitude, so share this pleasure by immersing yourself in the lives of others and trying to see the world from their point of view. That’s what four students from Claremont McKenna College did - they traveled to Pena Blanca, Guatemala to get a true perspective of extreme poverty and engage with the people living in this village who struggle to survive on $1 per day. Experiencing the resiliency of people living in poverty changed the lives of Chris Temple, Zach Ingrasci, Sean Leonard and Ryan Christoffersen by grounding them from our materialistic, over-consuming reality and allowing them to learn about the everyday hardships that people must face simply just to survive another day. Now, these four men hope to change the lives of the 1.1 billion impoverished people who live on $1 a day by raising awareness, fostering inspiration and encouraging action.

Chris and Zach were kind enough to answer a few questions about the process that led to the creation of their newly released documentary ‘Into Poverty: Living On One Dollar’, which details their travels to Pena Blanca, their experiences of living on $1 per day for eight weeks, the issue of global poverty and how you can help.

Q | How did you come up with the idea for the trip and actually make it a reality?

We were studying economics and international development in school, but the issues we were reading about seemed so far from our daily reality. We constantly heard the overwhelming statistic that 1.1 billion people live under $1 a day, but growing up in Connecticut and Seattle, had little ability to understand the reality of life at that level. So we came up with the concept to live under $1 a day for two months ourselves. We knew that we'd never be able to truly replicate poverty but we did believe that this would be a valuable experience.

Having an idea and making it a reality are two very different things. We developed the idea over a 10 month period and applied for funding from 9 different sources but got rejected from all of them. We had no track record of making films and the project was different and potentially dangerous – making it difficult for someone to fund. Finally about a month before leaving, we got $4,000 from the Whole Planet Foundation, which was enough for our plane tickets and $1 a day each while there. Actually going was a difficult decision to make though. My family wasn’t particularly supportive and there was a lot of pressure to get a traditional internship with a consulting firm or investment bank.

Q | How did you prepare yourselves for a trip that is so different from the reality that you are used to?

Looking back, we were horribly unprepared for the trip, both physically and emotionally. But I’m not sure how we could prepare for what the following few months were going to bring. It may have been to our advantage that we didn’t have much time to think about the trip right before going because we were so busy with end of the year exams at school.

Photo credit: Living On One

Q | Why did you choose Pena Blanca for this experience?

We chose Guatemala because I (Chris) had been lucky enough to travel there a few years before and had fallen in love with the culture and people, especially the rural areas. When we thought of the idea for the documentary, we were studying economics in school, and were shocked to learn that in Guatemala almost 50% of the population lives in poverty and in rural areas 75% of the indigenous population lives in poverty. This was representative of rural poverty in many parts of the world, and an unimaginable problem that we wanted to learn more about.

We chose Pena Blanca specifically because we knew people at a nearby non-profit who had been to the community before, knew the average income, and knew that it was a safe community.

Q | At any point in the trip did you want to give up? How did you persevere through the tough times?

I (Zach) remember one morning when I woke up on our dirt floor after being bitten by fleas all night. I didn't know if we were going to have enough money for food that day let alone medicine for a parasite that Chris had just contracted from contaminated drinking water.

The discomfort of the dirt floor and fleas was definitely challenging but it was the stress of having a small, irregular income and not knowing what illness or disaster was going to hit us next that was really the hardest part.

These challenges made us realize just how innovative and strong the poor have to be to even survive. Seeing our neighbors strive to improve their lives, in the face of such hardship, inspired us to stay the 56 days and do everything we can to give back. We really built life-long friendships with them – friendships that transcend just this film – which is the most rewarding part. They inspired us to create this film that would inspire action through hope, not through guilt.

Q | Did you ever feel guilty knowing that you would return home in a few weeks to electricity, running water, an actual bed, etc.? How did you deal with those feelings?

The hardest part about the whole trip was leaving and knowing that our neighbors faced an unpredictable and extremely challenging future. I think a lot of people feel this sense of guilt when they come back from abroad, and they hide from those feelings instead of facing them. It seems like such a shame that we travel and build these amazing relationships and then never follow up again or keep in touch. What has been so lucky about this project is that we’ve been able to go back 3 times to Pena Blanca over the past few years and speak monthly on the phone with Chino, Anthony and Rosa. We’re even friends with Rosa on Facebook!

Technology allows us to stay connected around the world and continue to learn from one another and be there for one another in times of need.

Q | What is your advice for other college students who want to go on a service trip or get active about a topic they are passionate about?

I would encourage everybody to walk in somebody else’s shoes, if only for a few days. Through the experience, you’ll gain empathy for someone else’s reality and never judge, disregard, or ignore a person like them in the future. For me (Chris), I will never see a hotel janitor in the same light. Anthony, one of our neighbors, was one of the most generous and intelligent people I’ve ever met, yet he cleaned hotel rooms for a living. This might not be considered the most accomplished job to some, but his formal job and steady paycheck were the envy of the entire town.

There are so many ways for someone to make a difference in the world. It doesn’t have to be an international service trip, it could be mentoring a low-income student nearby or an environmental project. What’s important is that you give something, your time, your money, or your skills. These actions will help you find your inspiration and lead you down a path you would have never expected. I was going to intern for an investment bank for the summer, but instead went to Guatemala, and my whole life path was changed.

Photo credit: Sean Leonard

Q | Overall, what have you learned from these experiences and how have they changed your life and outlook?

If there’s one thing I walked away with from Guatemala, it’s that small things can have a huge effect on the lives of the extreme poor. By understanding this, we can feel empowered that change is possible.

For billions of the poor it is not a choice to live with less. What is most troubling is not that they live with less material things but that they live with less opportunity to improve their lives. They often don't have access to things we take advantage of everyday like education, financial services, nutrition, healthcare and even access to clean water. For those who have these resources it is our responsibility to join together and make a difference in the world.

One of our closest friends in Peña Blanca is Rosa, a 21-year-old woman, who has this dream of becoming a nurse. Sadly, in the 6th grade, she was forced to drop out of school because her father got sick. Years later, with the help of a microfinance loan of only $200, she was able to start her own weaving business and with the profits, begin paying for herself to go back to school and keep her dream alive. Rosa is one of the smartest, most motivated people we have ever met, all that she lacked was an opportunity to improve her own life.

Learn, Connect, Act.

Learn more about Living On One

Connect via Facebook and Twitter

1. Spread the word. Our film just released for anyone to download it on our website or iTunes.

2. Give a Donation. You can support education, clean water, or microfinance for the community of Pena Blanca by giving to one of our impact partners here: www.LivingonOne.org/changeseries

3. Buy Shirts or Sandals. Our shirts are handmade by the star of our film, Rosa, and help pay for her education. The sandals support the health and education of Guatemalan children like Chino.

4. Contact High School teachers and tell them to show the film and/or bring us to speak so we can create a generation of active global citizens.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN CONSCIOUS MAGAZINE

CARLY LONG

Carly Long is a contributing writer and researcher for various publications, including Conscious Magazine. Her articles have focused on companies that incorporate social good, as well as individuals who work to improve the lives of others. Carly is also a self-taught painter, as she developed an original technique of custom painted photographs.

PERU: Sex Worker Runs for Congress

Angela Villon has earned a living as a sex worker for over 30 years. Now she plans to fight sex trafficking and violence against women and girls by running for congress in Peru's upcoming elections.

Las Palmitas and the “macro mural” in its final stage. Photo taken with permission from the Germen Crew collective's Facebook page.

MEXICO: The Enormous Mural That Made This Neighborhood 'Magical'

In the center of a small neighborhood located in the city of Pachuca, Hidalgo, the largest graffiti mural in all of Mexico, painted onto a canvas of 200 homes, was inaugurated this July. But the “macro mural” has done much more than simply give some color to the hillside district of Las Palmitas, a predominantly rural neighborhood with a certain degree of poverty and crime.

The collective effort has created jobs, reduced youth violence and instilled a sense of community spirit, turning Las Palmitas into what the project leaders have dubbed the “first magical neighborhood” — a play on the Mexican government’s separate initiative to promote “magical towns” (Pueblos Mágicos) as tourism destinations.

Leading the project was the independent Mexican collective the Germen Crew (Seed Crew), composed of urban artists specializing in graffiti art, mural painting and audiovisual documentary. A group which, through public and street art, aims to give new meaning to public spaces and restore social fabric for the benefit of communities. Their Facebook page reads as follows:

“Our work is an artistic offering for our cities. It is through colors, forms, textures, and mixed media that we share our way of making and understanding art. We seek to detonate the seed of possibility by strengthening the hearts and enthusiasm of those who live in the places we step into. We want to give new purpose to public spaces, making them more useful for their inhabitants, places that educate, motivate, and help to support and sprout new relationships with the surrounding citizens and the expressions that converge there.”

Beyond the collaboration of the local and federal government, which facilitated the materials needed, the project was fueled in large part by the active participation of the 452 families that live in Las Palmitas (about 1,808 people). The residents were consulted throughout the three months that the project lasted, and they also took part in various cultural activities that were held at the same time: workshops, lectures, and tours, all with the objective of reducing juvenile delinquency.

'So much harmony and coexistence'

In the above video documenting a workshop on lantern balloons, Las Palmitas residents remarked that the artistic activities were having a positive impact on the neighborhood:

“For us it is a festive day in our district, because we are experiencing things we had never experienced before.”

“I see so much harmony and coexistence, above all in our families. I believe that with these events my neighborhood will improve greatly and I don’t think there will be so much delinquency.”

In an interview with ideas magazine Planisferio, the Seed Crew explained that what makes their approach innovative is their focus on painting not institutional spaces, but rather public plazas, markets, and even marginalized areas with significant crime rates. At the same time, they said, their success is the fruit of their collective efforts and group dynamics.

'The first magical neighborhood of Mexico'

The statement “Color is magic” opens a brief video that documents the transformation of Las Palmitas to a vibrant, colorful community.

With more than 13 years in existence, the Crew has undertaken projects in the Jamaican Market of Mexico City; in the esplanade of the new towns in Ecatepec in Mexico; and in Miravalle, Guadalajara, among many others. Now, they have achieved their aim of transforming Las Palmitas into what they call the “first magical neighborhood of Mexico,” and everything seems to indicate that there is still more to come.

More information about the work of Seed Crew can be found on their pages on Facebook and Instagram, and on their channel on YouTube.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON GLOBALVOICES

GIOVANNA SALAZAR

Although Giovanna is originally from Mexico City, she currently resides in Amsterdam as she works toward a masters in the study of new medias and digital culture. Her professional endeavors have always been motivated by a commitment to human rights, and hopes to combine knowledge about communication media with community activism and engagement.