A group of friends started a journey to Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Uruguay, Paraguay and Southern Brazil in their old and rusty Land Rover. They encountered lots of winds, emptiness, pampas, bustling cities, animals, deserts and waterfalls—all wrapped up in just under 6 minutes. Enjoy the ride!

The Largest Salt Flat in the World in Bolivia

Bolivia’s Salar de Uyuni is one of the country’s wonders. Despite the amount of tourists it still preserves its beauty.

Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia. Giacomo Buzzao. CC BY 2.0.

Located in the Andean Plateau in South America, the Salar de Uyuni is the largest salt flat in the world. It is in southwestern Bolivia, close to the border between Bolivia, Chile and north of the Argentinian border. It is over 4,050 square miles and the salt crust stretches to the horizon. It is also 10,000 feet above sea level, as it is located in the Andes. Since the salt is white, the Salar de Uyuni appears to be a large white desert, but during the rainy season, nearby lakes overflow, rivers empty into the salt flat and it becomes filled with water.

Though the seeing the dry, white salt stretch for miles is beautiful, when the salt flat is filled with water, it creates a clear mirror-like lake. Generally, there are only a few centimeters of water so it is still possible to walk on it, but as the weather is unpredictable, some areas become restricted for safety. The salt flat is mostly waterproof, but too much rain will melt some of the salt and make it dangerous to walk on. However, during this time, Salar de Uyuni turns into the world’s largest natural mirror, reflecting the light from the sky. The winter months also have clear skies that offer beautiful stargazing opportunities, the reflected stars only adding to the salt flat’s wonder.

The Salar de Uyuni is large enough to be seen from space, and it contains 10 billion tonnes of salt. 70% of the lithium in the world is also mined from this salt flat. The Salar de Uyuni was created 40,000 years ago, after Lake Michin evaporated. Over the course of its slow evaporation, the salt hardened and created a crust that formed the area into what it is today. In addition, there is still water underneath the salt that continues to evaporate as temperatures rise, which adds more salt to the surface.

Beyond the scientific explanation for the Salar de Uyuni’s creation, the locals have passed on their own legends. In one of them, one of the nearby mountain goddesses, Yana Pollera, gave birth to a baby that two other mountain gods fought over. They both believed themselves to be the father, and Yana Pollera sent her child away to where the salt flat is located today and flooded the area with her milk that eventually evaporated into salt so it would survive. Another legend claims the flat was formed because after two mountain gods were married, the husband left and the wife cried until her tears created the Salar de Uyuni.

Dawn at Salar de Uyuni. Trevor McKinnon CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Because of its location, there are many tours leaving from Bolivia and Chile, and many of them stretch over the course of multiple days in order to get the most out of the natural beauty. Planes, buses and trains are all able to get to Uyuni, the town closest to the salt flat, but there are also tours from Tupiza, a town south of Uyuni, and San Pedro de Atacama, a town in Chile.

RELATEAD CONTENT

Katherine Lim

Katherine Lim is an undergraduate student at Vassar College studying English literature and Italian. She loves both reading and writing, and she hopes to pursue both in the future. With a passion for travel and nature, she wants to experience more of the world and everything it has to offer.

Peru and Bolivia: A Short Film Capturing the Beauty of the Mountains

High in the Andes mountains, the people of Peru and Bolivia inhabit one of the most unique landscapes in the world. From rainforests to rocky slopes, towns and cities coexist with the wildlife and the natural topography in a way that seems as though they were created by nature as well as human innovation.

The people living in these cities blend historical traditions with the technological advancements of the modern age— retaining the beauty of their culture, dress, and craftsmanship and passing it down to the next generation. This video, directed and edited by Baptiste Lanne, highlights the beauty of both Peru and Bolivia’s varied climate, geography, and people, illustrating the complex balance of humanity and nature. The breathtaking scenes are interspersed with shots of people’s daily lives; both are equally beautiful.

8 Surprisingly Vibrant Desert Destinations

Deserts are much more than the beating sun and rolling sand dunes we often picture. These eight destinations showcase the incredible natural beauty of the desert, from salt flats and chalk formations to mountains and glaciers.

Though deserts are often thought of as just hot, dry expanses of sand, they come in a variety of climates and landscapes and hold some of the world’s most fascinating natural formations. Deserts “are areas that receive very little precipitation,” making them arid but not necessarily hot and sandy. Many deserts are mountainous, and others are large expanses of rock or salt flats. Though their arid environment makes water in deserts scarce, they are far from lifeless. Plants and animals, including humans, have adapted to desert life. One-sixth of the Earth’s population lives in deserts, which are found on every continent.

These eight desert destinations range from freezing to boiling in temperature and are all unique, with their own attractions and plant and animal life. Each of these stunning deserts is worth a visit, and they may change your opinion of the desert as a stark, lonely place to one of beautiful landscapes blooming with culture, history and life.

White and Black Deserts, Egypt

Located just a few hours from Cairo, Egypt’s White and Black deserts are two stunning and underappreciated visitor attractions. The White Desert is located in the Farafra Depression, a section of Egypt’s Western Desert, and boasts some of the most unique geological landscapes in the country. Incredible wind-carved white chalk formations rise from the sand in the shapes of towering mushrooms and pebbles, giving the White Desert its name. The White Desert stretches over 30 miles, and the most visited area is the southern portion closest to Farafra. To the north of the White Desert is the Black Desert, where volcanic mountains have eroded to coat the sand dunes with a layer of black powder and rocks. In the Black Desert, visitors can climb up English Mountain and look out over the landscape. The Egyptian Tourism Authority recommends booking a tour to explore the deserts in depth, and travelers can even stay in the White Desert overnight.

Joshua Tree National Park, California

Joshua Tree National Park in Southern California is where two different desert ecosystems meet. Parts of the Mojave and the Colorado deserts are both found in Joshua Tree, along with a distinctive variety of plant and animal life. The Joshua tree, the park’s namesake, is the most identifiable of the plants, with its twisted, spindly branches and spiky clusters of greenery. Some of the park’s most popular attractions are Skull Rock; Keys View, a lookout with views of the Coachella Valley and the San Andreas Fault; and Cottonwood Spring Oasis, which was a water stop for prospectors and miners in the late 1800s. Joshua Tree National Park has roughly 300 miles of hiking trails for visitors to explore. The park is open 24 hours and can be visited at any time of the year, but visitation rises during the fall due to the cool weather and is at its height during the wildflower bloom in the spring.

Atacama Desert, Chile

Trips to the Atacama Desert in northern Chile are likened to visiting Mars on Earth. The dry, rocky terrain is so similar to that of Mars that NASA tests its Mars-bound rovers here. The Atacama Desert, the driest desert on Earth, spans over 600 miles between the Andes and the Chilean Coastal Range. Some weather stations set up in the Atacama have never seen rain. Despite its dryness, the desert is home to thousands of people, as well as plants and animals. People have been living in the Atacama Desert for centuries; mummies were discovered in the Atacama dating back to 7020 B.C., even before the oldest known Egyptian mummies. Attractions in the Atacama Desert include El Tatio geyser field, the Chaxa Lagoon, the Atacama salt flats, and sand dunes over 300 feet tall. The Atacama Desert is also said to have some of the clearest night skies in the world, making it perfect for stargazing. It is best to avoid a trip to the Atacama during the summer months, as the high temperatures make for a sweltering visit.

Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia

The world’s largest salt flat, Salar de Uyuni, covers 3,900 square miles in the southwestern corner of Bolivia. Salar de Uyuni is so large it can be seen from space and holds an estimated 10 billion tons of salt. Beneath the salt flat is approximately 70% of the world’s lithium reserves. This lithium is carefully extracted and used for powering laptops, electric cars and smartphones. Salar de Uyuni is surrounded by scenic lakes, geysers and rock formations, and is one of the world’s most beautiful and untouched natural landscapes. Tours of Salar de Uyuni take visitors to the Valley of Rocks; Morning Sun, which is home to geysers and mud pots; Colchani, a salt-processing village; and the Polques Hot Springs, where travelers can soak in warm thermal water. The landscape of Salar de Uyuni changes based on the seasons, so travelers should plan their visits around what they want to see. From July to October, access to all sites of Salar de Uyuni is unrestricted, but during the rainy season from December to April, visitors may be able to witness the salt flat’s famous mirror effect, where a thin layer of water over the salt transforms the land into the world’s largest mirror.

Tanque Verde Ranch, Arizona

Located just outside of Tucson, Arizona, near Saguaro National Park and the Rincon Mountains, Tanque Verde Ranch gives visitors “the ultimate dude ranch experience.” The ranch sprawls over 640 acres and stocks over 150 horses. Visitors to the ranch can get a real-life cowboy experience, including horseback riding and team penning. Riders of all experience levels will find something to do at Tanque Verde, where visitors can take beginning, intermediate and advanced lessons and then go on a sunrise or sunset trail ride through the Arizona desert. Tanque Verde Ranch offers kids’ riding activities too, as well as activities for non-riders such as yoga, mountain biking, fishing, swimming and pickleball. Visitors should pack long pants and closed-toe shoes if they plan to ride, and casual wear is appropriate for all non-riding times. Trips to the ranch usually last around four days, and visitors stay on the property. Tanque Verde Ranch is open to visitors year-round.

Gobi Desert, Mongolia

Spanning most of southern Mongolia and its border with China, the Gobi Desert contains stunning views and years of history. The region was once populated by dinosaurs, and some of the best-preserved fossils in the world were found near the Flaming Cliffs of Bayanzag. The Gobi Desert showcases a variety of natural beauty, from towering sand dunes to incredible white granite formations. Dry desert plants that come to life after rain make the Gobi unique, as well as ”saxaul forests” made up of sand-colored shrubbery. Visitors to the Gobi Desert should explore the Khongor Sand Dunes, an area that offers rocky and mountainous terrain in the south, dry and barren terrain in the center, and several oases in the north. Other major attractions are the Flaming Cliffs of Bayanzag, where red clay seems to glow in the sun, and the Gobi Waterfall, which looks like a city in ruins but is a completely natural formation. The best time to visit the Gobi Desert is either in late spring or in autumn, when the weather is neither too hot nor too cold.

Nk’Mip Desert, Canada

Also called the Okanagan Desert, Canada’s Nk’Mip Desert contains the most endangered landscape in Canada. Located in Osoyoos in British Columbia, the Nk’Mip Desert Cultural Center is a 1,600-acre area of the Okanagan Desert managed by the Osoyoos Indian Band, and is the only fully intact area of desert in Canada. The desert is situated in a semiarid microclimate. The cultural center was designed to be eco-friendly and resembles the traditional winter homes of the Osoyoos Indian Band. Visitors can explore the desert on walking trails, which are surrounded by sage, prickly pear cactuses and antelope brush, as well as sculptures of desert creatures and native peoples by Smoker Marchand. The trails take visitors through a traditional Osoyoos village, where they will find a traditional sweat lodge and pit house. Many visitors prefer to explore Nk’Mip Desert in the summer due to the region’s relatively cold winters.

Patagonian Desert, Argentina and Chile

The Patagonian Desert is South America’s largest desert and the seventh-largest in the world. It covers parts of southern Argentina and Chile, and is a cold desert, sometimes reaching a high temperature of 68 degrees Fahrenheit. The Patagonian Desert is home to two national parks: Torres del Paine National Park in Chile and Los Glaciares National Park in Argentina. Torres del Paine and Los Glaciares aren’t typical desert environments, but since the Patagonian is a cold desert, its landscape is different from that of most deserts. Before the Andes were formed, the Patagonian Desert was likely covered by temperate forests, so the region containing the desert, Patagonia, is extremely ecologically and geographically diverse. Torres del Paine National Park is known for its towering granite structures, which were shaped by glaciers. Los Glaciares is home to large glaciers, as well as scenic mountains, lakes and woods. The Cueva de las Manos, or “Cave of Hands,” is a series of caves in Argentinian Patagonia which are filled with paintings of hands dating back to 700 A.D., likely made by ancestors of the Tehuelche people. Tehuelche people live in Patagonia today, some still following a nomadic lifestyle. The best time to visit Patagonia is generally said to be in the summer (December to February), when the days are warm and the fauna is in full bloom, but there are merits to exploring the area at all times of year.

Rachel Lynch

Rachel is a student at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY currently taking a semester off. She plans to study Writing and Child Development. Rachel loves to travel and is inspired by the places she’s been and everywhere she wants to go. She hopes to educate people on social justice issues and the history and culture of travel destinations through her writing.

Evo Morales Returns in Triumph to Bolivia, Ending a Year in Exile

One year after he stepped down amid a contested election, the popular left-wing leader is back. Will he be content with his supporters’ love, or will he seek power as well?

Evo Morales waving the Wiphala, a symbol for South America’s Indigenous people. Brasil de Fato. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Exiled leaders rarely return so triumphantly. Evo Morales, president of Bolivia for 14 years before fleeing the country in November 2019, greeted a jubilant crowd when he crossed the border from Argentina and trekked to his home province of Chapare. Many expected a more forceful return, perhaps a march to the seat of government in La Paz. Rather, Morales traveled to where he started his political career at the precise moment when that career seems set to either end or begin again.

If Morales plans to kick-start a new phase in his political career, he reenters in a much better position than when he started. Born to a poor family in the Orinoca region in 1959, his family moved with countless other families from the highland altiplanos to work on lowland coca farms, which provided poor Bolivians the best shot at a livable wage. The young Evo became a union leader, fiercely advocating for the rights of farmers when the United States’ war on drugs demanded the Bolivian government slash its supply of coca, its most profitable crop. In Bolivia, people chew on it or brew tea, but one ton of leaves can be refined into two pounds of cocaine base paste.

A farmer pruning coca. Erik Cleves Kristensen. CC BY 2.0.

Morales’ experiences there fostered a brand of politics staunchly devoted to the poor and Indigenous communities through the institution of socialism. He joined and soon transformed the Movement for Socialism party (MAS) and became a one-term congressman. After leading violent street altercations that forced two presidents to resign, his ambitions expanded to the national realm. In 2006, the Bolivian people voted him in as president, beginning a 14-year-long tenure which would prove revolutionary.

For one, he was the first Indigenous president since the country’s independence in 1825. In a nation that is 42% Indigenous, this seems strange, but centuries of colonization and racism led to a society of haves and have-nots. An ethnic Aymara, Morales expanded MAS’s appeal to all Indigenous people, chafing many Whites and Mestizos who supported MAS in far fewer numbers. Some Indigenous communities found Morales’ embrace of Indigenous peoples hollow; he allowed drilling in forest reserves and expanded the amount of land settlers could clear.

Man without a plan. Alain Bachellier. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Most of all, however, he presided over what many view as an economic miracle. Morales’ government reduced by two-thirds the amount of people living on less than $1.90 a day, the World Bank’s definition of extreme poverty. The high price of petroleum, another of Bolivia’s largest exports, allowed his administration to invest heavily in innovation and modernization. The widespread prosperity led many to ignore Morales’ authoritarian streak. He would often jail critics and journalists while piling lawsuits on his political rivals.

But when Morales ran for a fourth term against constitutional term limits, opponents found it unforgivable. A pause in vote-counting led many to believe he planned to rig the election, so thousands stormed the streets to protest the election results. Clashes broke out between pro- and anti-Morales protesters; 36 people died amid the violence. Once the military “recommended” Morales step down, he boarded a plane to Mexico and left Bolivia in the hands of little-known senator Jeanine Anez.

She was a right-wing politician with exactly the opposite views of Morales. Where he proudly represented Indigenous peoples, Anez called them “savages.” (In his triumphant return, Morales sarcastically quipped, “The Bolivian right and the global right should know: the savages are back in government.”) Anez presided over an economic slump due to political unrest and COVID-19. She governed for 11 months before the electorate put in office Morales’ own protege Luis Arce.

Morales’ protege Luis Arce. Casa de América. CC By-NC-ND 2.0.

A bland, uncharismatic technocrat, Arce won broad appeal precisely because he was Morales’ choice. He engineered the economy during Morales’ presidency, so he can take credit for much of Bolivia’s prosperity. His support from the former president may prove both a blessing and a curse, however. He will struggle to distance himself from a controversial figure who still holds strong sway over MAS. His primary responsibility will be to maintain distance from Morales to the greatest extent possible.

For the time being, however, Morales will enjoy his warm welcome home. Crowds gleefully waved the Wiphala, a colorful checkered flag representing Indigenous peoples. Supporters dressed in their finest, most colorful Indigenous attire to celebrate his homecoming. Luis Arce neither met him in Chapare nor sent him a word of greeting. So far they hold no communication. For the sake of Bolivia’s democracy, many hope it will stay that way.

Michael McCarthy

Michael is an undergraduate student at Haverford College, dodging the pandemic by taking a gap year. He writes in a variety of genres, and his time in high school debate renders political writing an inevitable fascination. Writing at Catalyst and the Bi-Co News, a student-run newspaper, provides an outlet for this passion. In the future, he intends to keep writing in mediums both informative and creative.

Following the Removal of Evo Morales, Anti-Indigenous Sentiment Explicit in Bolivia

In the aftermath of the ouster of former President of Bolivia, Evo Morales, many suspected a right-wing coup had taken place. Now, a month later, the status of Indigenous peoples in Bolivia hangs in the balance.

“Evo Morales speaking to a man wearing the Lluch’u, the knit cap typical to Andean indigenous peoples.” Sebastian Baryli. CC BY 2.0

In 2005, Evo Morales, of Aymara indigenous descent, was elected to become the first indigeneous President of Bolivia. Bolivia identified itself as a plurinational state following the ratification of a new Constitution in 2009, and is home to more than 36 indigenous peoples. In 2017, an estimated 48% of the population of Bolivia above the age of 15 was of indigeneous origin. Morales’s party, Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS--Movement Towards Socialism), represented a growing progressive force against the backdrop of the historically-conservative nation. Morales saw significant success over his three terms, stabilizing the Bolivian economy, spurring economic growth, reducing poverty significantly and bringing those living in extreme poverty down to half its previous rate, while heightening literacy rates across Bolivia. Under Morales, Bolivia became a more inclusive place: he instituted the Wiphala, which represents the plurinational status of Bolivia, as the nation’s second flag, and promoted a previously unparalleled number of women to his cabinet.

In 2016, Morales held a referendum in order to extend the term limits established within the 2009 Constitution, which was ultimately rejected in a 51% to 49% vote. However, in 2018 Morales appealed to the Bolivian Constitutional Tribunal, which allowed Morales to run for re-election for a fourth term as President of Bolivia. Although Morales was elected for a fourth term in October of 2019, an audit by the Organization of American States determined the election illegitimate, and many had questioned the legality of the Tribunal’s decision in 2018 even before the election came to pass. In the midst of protests that left over 30 dead and 700 injured, and under extreme pressure from the military, Morales stepped down and fled to Mexico.

In the immediate aftermath of the ouster of Morales’s administration, many questioned whether there had been a coup. Calls for Morales’s resignation began in the right, and gained traction; ultimately, Morales resigned following military coercion against him and his party. Although there has been a precedent for right-wing coups in Latin American history, especially aided and abetted by the United States, the case of Morales’s administration is complicated. While the military intervention does constitute an illegal seizure of power, the discontentment for Morales did not arise in a vacuum. Opposition leaders and former supporters alike felt that a fourth term meant a clear violation of the Constitution Morales himself had worked to implement, and many more agreed that Morales had begun to lose touch with the population after 14 years in office. Many of his former indigenous supporters were angered by Morales’s approval of a hydroelectric dam in indigenous territory.

Morales’s resignation triggered many of his top officials and closest political associates to resign as well, leaving the presidential seat to Jeanine Añez, formerly vice president of the Senate of Bolivia. The Constitution stipulates that a new election must be called for within ninety days, and upon taking power Añez openly assured the country that her taking power was purely transitional. Many have doubted Añez’s words, and have called for her resignation given her connection to the right-wing opposition in Bolivia.

Anti-indigenous graffiti has appeared throughout Bolivia, as well as videos depicting police cutting the Whiphala emblem from their uniforms. These actions have been empowered by Añez herself, in the past implicated in anti-indigenous tweets, who has called for police repression of pro-Morales protestors. Notably, Añez’s cabinet, even if temporary, contains no indigenous representatives, and it seems that she has already begun the process of rolling back strides made under Morales towards socialism and inclusion. In this way, growing worries that the rise of a new right-wing government will revive festering anti-indigenous sentiment are well-founded. Ultimately, the political uprising in Bolivia leaves the future of indigenous rights in danger, as outrage towards Morales has opened the floodgates for discrimination against the indigenous population as a whole.

Hallie Griffiths

Hallie Griffiths is an undergraduate at the University of Virginia studying Foreign Affairs and Spanish. After graduation, she hopes to apply her passion for travel and social action toward a career in intelligence and policy analysis. Outside of the classroom, she can be found, quite literally, outside: backpacking, rock climbing, or skiing with her friends.

Lands of Wind: A Journey Across Peru and Bolivia

A two months journey across Peru and Bolivia, from countrysides to cities, passing by jungle and mountains, capturing lives and landscapes of these two wonderful and inspiring countries.

Directed and edited by Baptiste Lanne.

VIDEO: Samuel in the Clouds of Bolivia

In Bolivia, the glaciers are melting. Samuel, an old ski lift operator, is looking out of a window on the rooftop of the world. Through generations his family lived and worked in the snowy mountains, but now snow fails. While scientists are discussing and measuring ominous changes Samuel honors the ancient mountain spirits. Clouds continue to drift by.

5 Ways to Make a Positive Impact while Traveling in Bolivia

As one of the poorest countries in Latin America, Bolivia is a nation that, more than most, would benefit from your tourism. However, a historic lack of investment in infrastructure throughout the country and a reputation of political instability has left this nation neglected by foreign visitors.

Despite being more difficult to explore than neighboring Peru, Argentina or Brazil, Bolivia is a country that shouldn’t be missed. It has a wealth of diversity of natural landmarks, from the soaring Andes Mountains to the huge plains of salt flats to the Amazon jungle, as well as tiny communities inhabited by local, indigenous people ready to share their culture with curious travelers – and who really benefit from the income that responsible, considered tourism brings.

So here are 5 ways that you can do your bit to make a positive impact when you’re traveling in Bolivia.

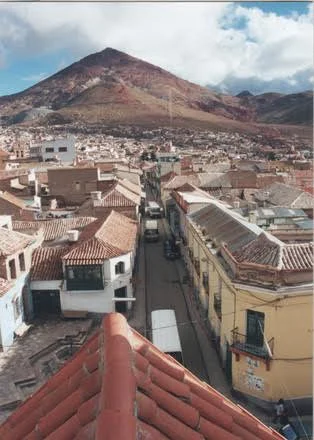

Potosi

1. Go Local

Many of us are more comfortable booking tours ahead of our trip to ensure that our visit runs smoothly and no time is wasted. But it can be difficult to know exactly how much of the money you’re paying is being invested into the country you’re visiting and whether the local people there are actually getting a fair deal.

Instead, booking tours when you arrive or online with locally-run, sustainable tourism agencies based in Bolivia will insure 100% of your money goes directly to the local people, meaning you’ll have a positive, responsible impact through your tourism.

Luckily, Bolivia has a growing number of excellent, responsible companies to choose from. Some of the best include:

Condor Trekkers based in Sucre is a hiking tour agency that leads treks into remote villages in the Andes, with hikes passing along stretches of preserved Inca trail and to landscapes potted with dinosaur footprints. They feed all of their profits back into the communities through which their tours pass to support locally-run, sustainable development projects.

The San Miguelito Conservation Ranch, a short distance from Santa Cruz, is a private reserve and conservation project that protects a section of wetlands acknowledged as having one of the highest concentration of jaguars in South America. This eco-tourism project runs tours to spot the big cats, birds and other wildlife in the reserve and uses the profits to maintain this important habitat.

Nick’s Adventures, another company based in Santa Cruz, runs a series of tours throughout the country, including spotting big cats in Kaa Iya National Park, the only park in South America established and administered by indigenous people. This agency supports sustainable development by providing employment to local people as drivers, guides and cooks and replaces any cattle killed by jaguars to stop ranch owners from shooting the cats, thus meaning that no jaguars or other native wildlife have been killed since Nick’s Adventures began this project.

La Paz on Foot runs walking tours in La Paz itself, as well as hiking trips further afield to indigenous communities. These communities receive much of the profits and La Paz on Foot have established a series of sustainable development and biodiversity conservation projects.

Solace Trekking Tours based in La Paz takes visitors on cultural tours to indigenous communities to take part in workshops about dancing, weaving and other traditional activities, as well as running climbing, biking and hiking trips to remote villages. Some of the profits of these tours are used to support the indigenous communities that are visited, as well as others who are fighting to save their land and water from mining – something that is a real threat to both natural habitats and the livelihoods of local people.

2. Don’t bargain too hard

Like many Andean countries in South America, artisanal goods of fluffy llama wool jumpers and delicate jewelry are hawked by locals on their stalls in every city and travelers are always keen to get a good bargain. But unlike parts of Asia and India where haggling hard is par for the course, in most of South America and particularly Bolivia, it’s not always the case.

Yes, you should expect prices to be higher for you; unfortunately, as a foreigner you will be charged an inflated rate. Negotiating a small reduction is sometimes possible, but most of the time, you shouldn’t try and push for prices that are vastly lower.

Shop around a bit and get a feel for what things cost, but follow your conscience with what you spend. Saving a few dollars on a jumper probably means very little to you in the long run, but in a country where 45% of people live in poverty and earn less than $2 a day, avoiding haggling sellers into the ground is the responsible thing to do.

3. Get off-the-beaten track

Most travelers in Bolivia stick to the main gringo triangle: La Paz, Sucre and Uyuni. And while these are certainly highlights of the country, other places also need the investment that tourism brings.

Towns such as Rurrenabaque, the best place in the country to access the Amazon Jungle, really need the support of responsible tourists. Once receiving lots of Israeli visitors (because of an Israeli who got lost in the jungle here a few decades ago and wrote a book about his experiences), numbers have dwindled since the Bolivian government decided to support Palestine and introduced a fee for Israelis entering the country.

Tourism is currently at a record low in the region and desperately needs travelers who are keen to visit. Check out sustainable operators, such as Mashaquipe Eco Tours, who charge fair prices and work responsibly to protect the jungle.

Another under visited location is Potosi. Here you can actually visit Cerro Rico (Rich Mountain), the famed mountain of silver that was plundered by the Spanish conquistadores.

Potosi is now the poorest city in the country and while many local people still attempt to make a living mining the last remaining minerals in the mountain, tours with ex-miners such as with Potochji tours, located in Calle Lanza, provide another option. Visitors can enter the mountain to see the terrifying conditions and ensure that their money supports ex-miners and the mining unions that now operate there.

4. Stay and volunteer

One of the most profound ways that you can help to support social development in Bolivia is by staying for a period of time to volunteer with grassroots projects. I’m always hesitant to volunteer for less than at least three months; I know that it takes time to learn about the organization and how best you can support its work.

In Bolivia, where few people speak English and where the culture is far more reserved than in a lot of other Latin American countries, it can definitely take time to start feeling like you’re making an impact.

Unfortunately, 90-day visas are the norm for most travelers arriving into the country, which can put a time limit on your volunteering. However, a visa of up to a year is not impossible to come by, but does require you to put a lot of effort into acquiring the necessary papers.

There are plenty of organizations that need your help, including Up Close Bolivia and Prosthetics for Bolivia in La Paz, Sustainable Bolivia in Cochabamba, Communidad Inti Wara Yassi in the Bolivian Amazon and Biblioworks and Inti Magazine in Sucre.

5. Or become an ambassador

But if you can’t commit to volunteering, how about becoming an ambassador or fundraiser for a charity based in Bolivia? While travelling in the country, take the opportunity to visit some of the many volunteering organizations to get an idea of what they do. When you’re back home, it’s easy to find a way to support their work.

You can become an ambassador who promotes the charity to their friends and social media followers, as well as signing up to make a regular donation. You could also volunteer long-distance by supporting fundraising efforts or helping with their social media accounts. Most importantly, you can spread the word about what they’re helping to achieve and find other volunteers or sponsors who can support their efforts.

Ultimately, Bolivia is a fascinating country to visit and so by traveling responsibly and considering how you can make a positive impact as a foreign tourist will support social development projects in increasing the quality of life for the Bolivian people.

STEPH DYSON

Steph is a literature graduate and former high school English teacher from the UK who left her classroom in July 2014 to become a full-time writer and volunteer. Passionate about education and how it can empower young people, she’s worked with various education NGOs and charities in South America.

GRINGO TRAILS

How do travelers change the remote places they visit, and how are they changed? GRINGO TRAILS, a new documentary film, offers answers—some heartbreaking, some hopeful. From the Bolivian jungle to the party beaches of Thailand, and from the deserts of Timbuktu, Mali to the breathtaking beauty of Bhutan, GRINGO TRAILS shows the dramatic long-term impact of tourism on cultures, economies, and the environment, tracing some stories over 30 years. Backpackers and local inhabitants tell startling stories of transformation, for good and ill.

This film will premiere at the Margaret Mead Film Festival at the American Museum of Natural History on October 19th.