There are 27 million human slaves in the world today, more than double the slaves in the whole transAtlantic slave trade. Lisa Kristine here documents slavery from Nepal to Ghana, from the Himalayas to India. As she says, there are dark corners in this world, and she exposes them through her images.

Read More

Men, women and children, entire families in fact, carry burdensome bricks, often as many as 18 at a time, in 130 degree heat.

A worker blends in with the bricks at a Nepalese kiln. Workers mechanically stack 18 bricks at a time, each weighing four pounds, and carry them to nearby trucks for 18 hours a day without any payment or compensation.

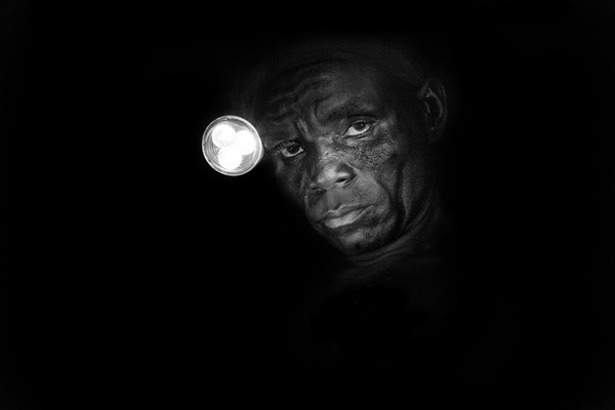

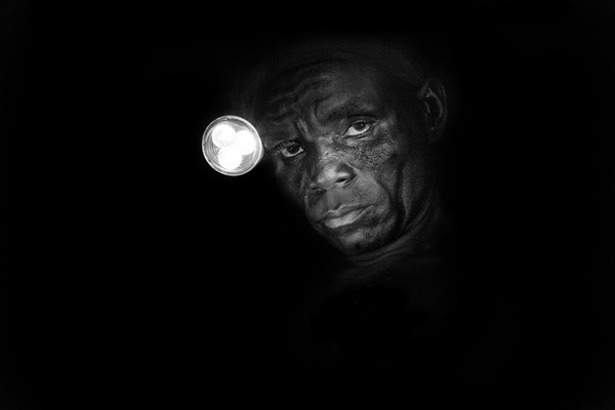

These gold miners have just come out of the shaft, their pants soaked from their own sweat. Most had spent all their money coming from the north hoping to strike it rich in legal mines. But legal operations require certifications. When they can't get a job, the men take high-interest loans or join groups of slaves in mines abandoned by legitimate operations.

Two hundred feet underground, a man labors in an illegal gold mine. He and others enslaved like him are underground for as long as 72 hours at a time.

Many of those enslaved had children with them while panning for gold, wading in waters poisoned by mercury that is used in the extraction process.

For this photo, I was escorted by women who had previously been enslaved themselves. They brought me down a narrow set of stairs leading to a green fluorescent-lit basement. This wasn't a brothel as such; it was a "cabin restaurants," as they are known in the trade -- venues for forced prostitution. Each has a small private room where slaves, some as young as seven, entertain and serve the clients, encouraging them to buy alcohol and food. These cubicles are small, dark, and dingy, each identified with a number painted on the wall, and partitioned by plywood and a curtain. The workers here often endure sexual abuse at the hands of the customers. Standing in the near darkness, I realized there was only one way out -- the stairs where I came in: no back doors, no windows large enough to climb through, no escape at all.

Child workers usually work from 1 a.m. to 5 a.m. on cold, windy nights to reel in nets weighing as much as 1,000 pounds when they are full of fish. Skeletal tree limbs submerged in Lake Volta frequently entangle the fishing nets, and and slave masters will throw weary, frightened children into the water to free the trapped lines, sometimes drowning them. I didn't meet one child who didn't know another who had drowned.

Fhanaian NGOs estimate that between 4,000 and 10,000 trafficked children are enslaved on Lake Volta, the largest man-made lake in the world. At first glance this image appears to be a family fishing in the lake, two older brothers and some kids. I was alarmed to learn that they were actually enslaved, working in plain sight. These children have been lost to their parents and are forced to work endless hours in boats on the lake, though they're unable to swim.

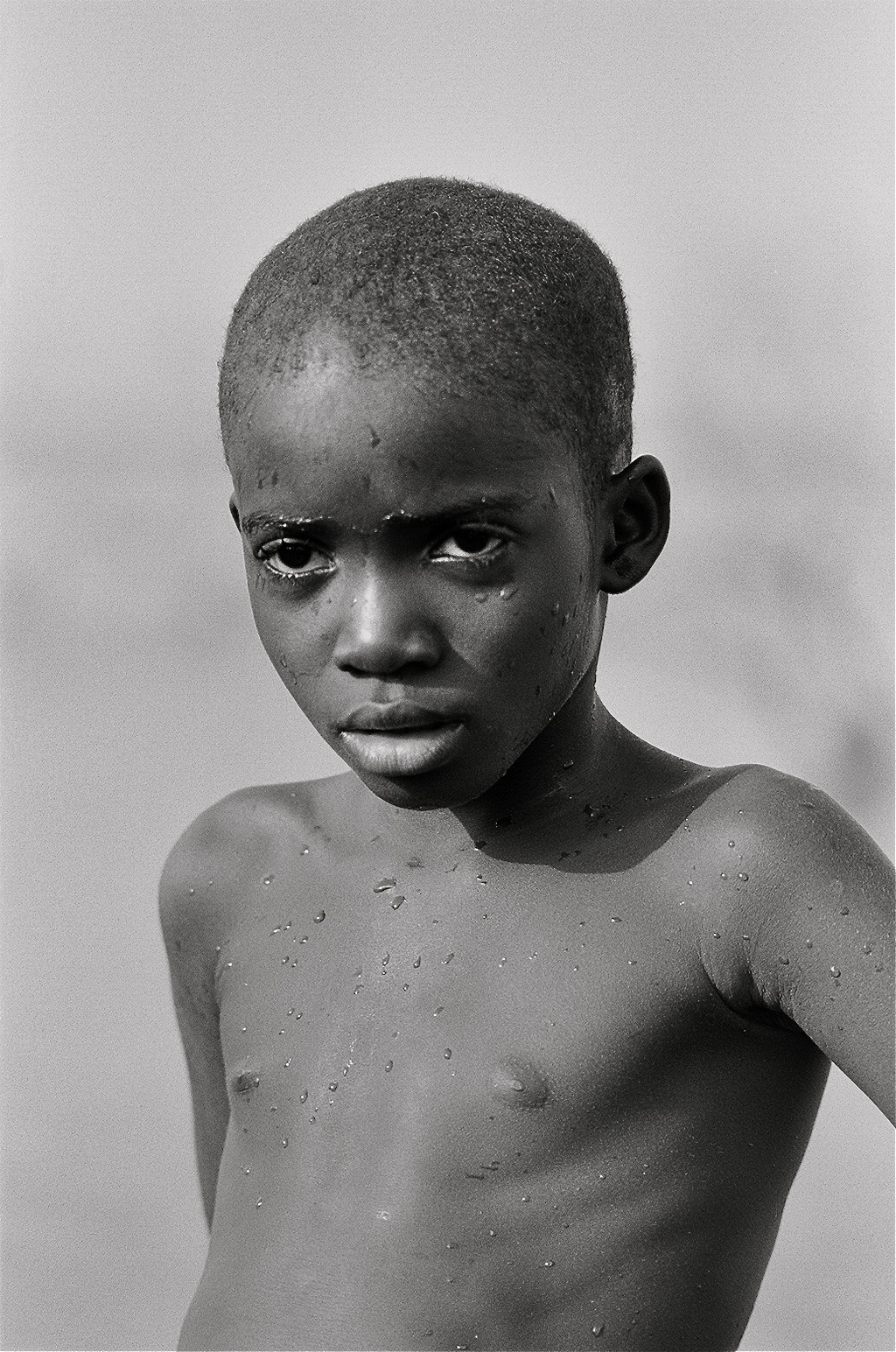

There are triumphs, too. Meet Kofi, a young boy who was rescued from slavery in a fishing village. I met Khofi at a shelter where Free the Slaves rehabilitate victims of slavery. He was bathing at the well, pouring big buckets of water over his head. Thanks to the efforts of organizations like Free the Slaves, today Kofi has been reunited with his parents, who were provided tools to make a living and to keep their children safe from human traffickers.

In the Himalayas I found children hauling stone for miles down steep mountain terrain to trucks waiting at the road below. These huge sheets of slate were heavier than the children themselves. The kids hoisted them with their heads using handmade harnesses made from sticks, rope, and torn cloth.

Uttar Pradesh, India: Slaveholders burned down these people's villages after they declared their freedom. Many of the neighbors wanted to give up, they were so frightened -- but the woman in the center encouraged them to persevere. Abolitionists helped them get a quarry lease of their own. Now they do the same backbreaking work, but they at least get paid for it, and they do it in freedom.

In India I visited a village where whole families were enslaved in the silk industry. This is a family portrait. The father (hands in black) and his sons (hands in red and blue) are held captive in a "silk dyeing house." The dye they work with is toxic. It's common for entire families to be enslaved for generations. My translator told me their story. "We have no freedom," they said. "But we hope, some day, we will be able to leave this house and make dyes in a place where we actually get paid for it."