Traffickers exploit the vulnerability of children for financial incentives from donors in orphanages and child residential homes.

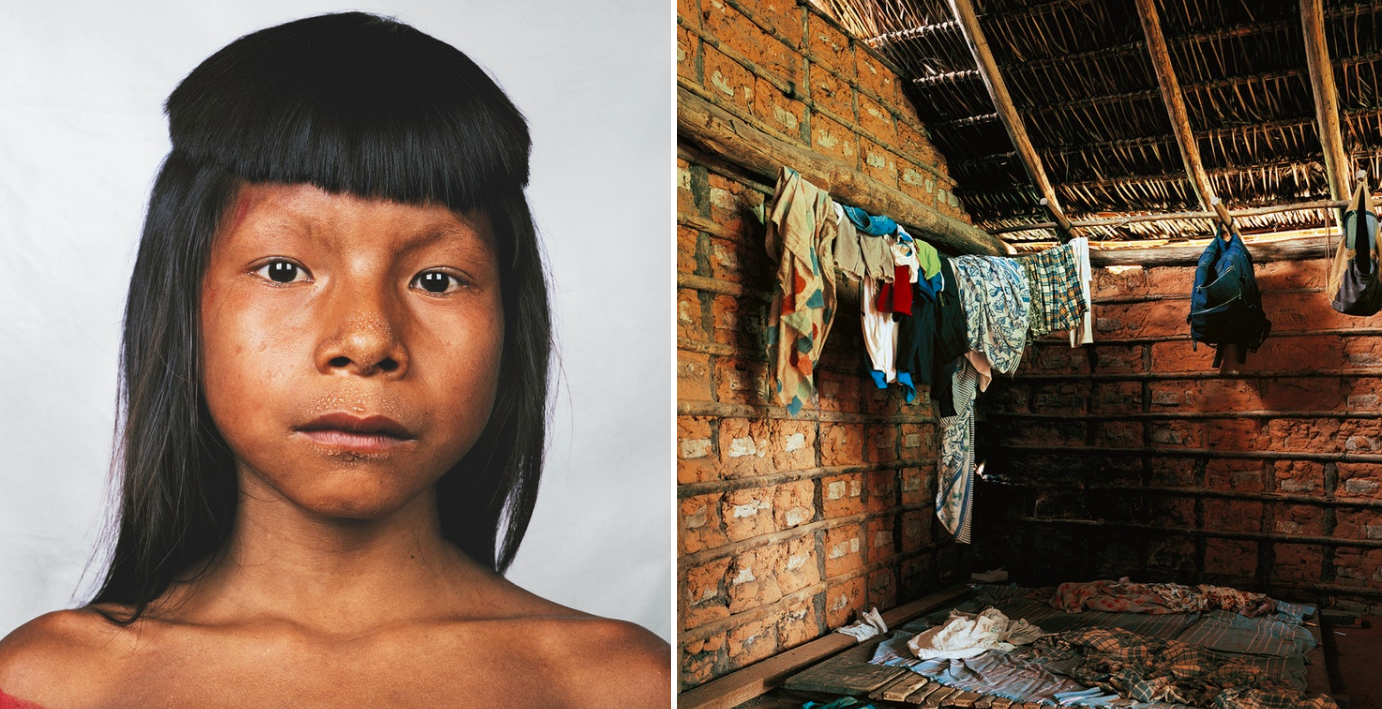

Two young Haitian children. CC0

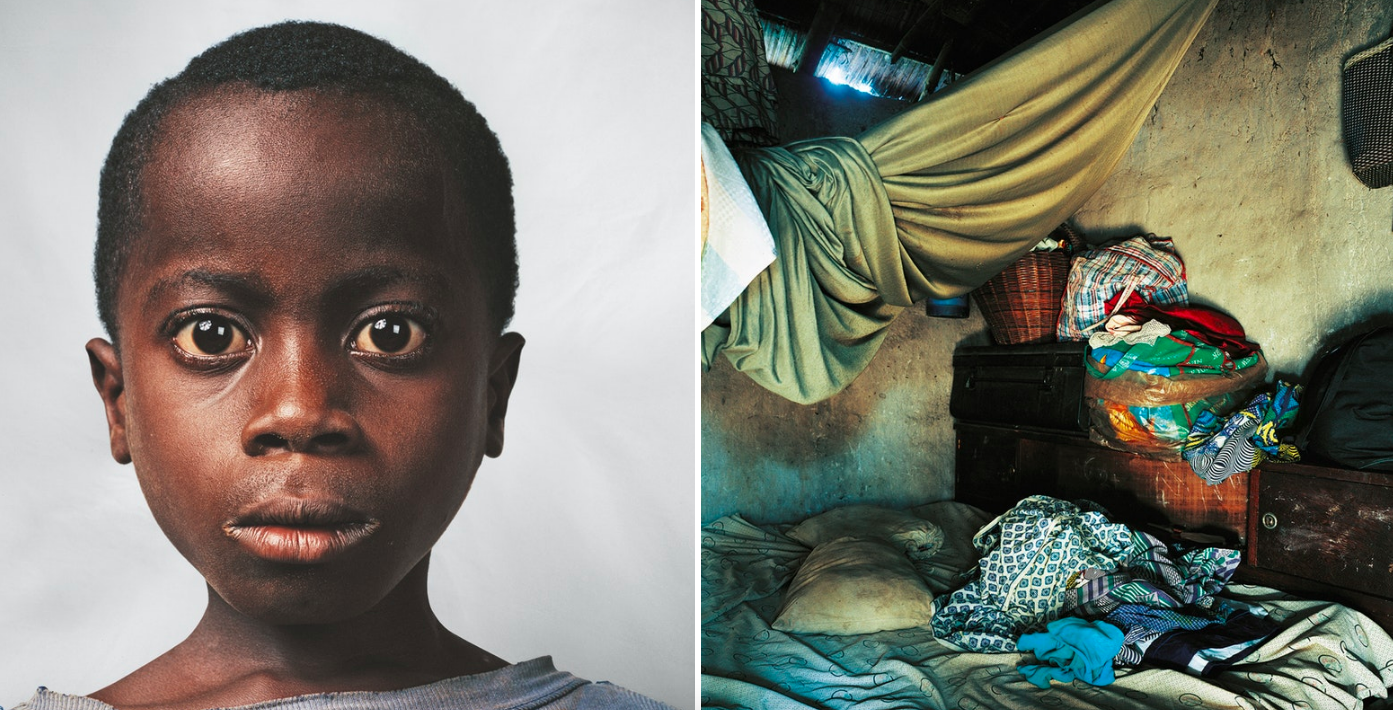

Across the globe, there are an estimated eight million children living in orphanages. Of this, 80% are not actually orphans and have at least one living parent. These children have been taken from their families and placed into children’s residential homes so that the caretakers can make a profit.

Orphanages, which are often viewed as a place of refuge for children, have begun using foreign generosity to profit off of their vulnerability. “Orphanage trafficking” involves children being recruited into residential care institutions for profit or exploitation and is not confined to any one country. This has sparked a new industry — orphanage volunteering — that has created a demand for institutions that will present children as ‘in need’ to make a profit from foreign donors. In Cambodia, for example, residential care institutions have increased by 75% in the last decade despite a decrease in the number of “real orphans.” Similarly, in Uganda, residential homes have increased the number of children under their care from 1,000 to 55,000 even with the subsequent decline in the prevalence of orphans themselves. This rise in residential institutions has taken place primarily in tourist hotspots so that orphanages can capitalize on financial incentives.

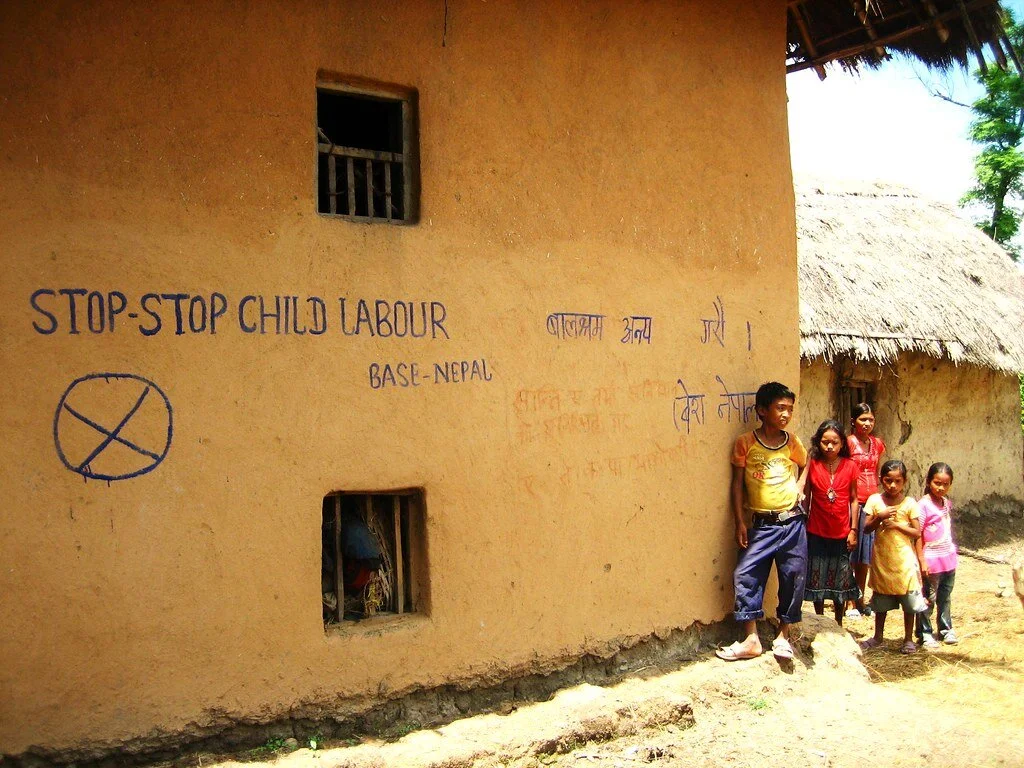

As a system that takes advantage of the international market and tourism business, this has become a global problem. A significant rise has been observed in post-conflict Nepal, beginning in 2006. During the Nepalese Civil War, traffickers posed as boarding school representatives and promised children and their families better living conditions in Nepal’s capital, Kathmandu. Rather than being taken to educational institutions, children were taken to under-resourced orphanages and declared “paper orphans.” This sales pitch has evolved accordingly, shifting from inter-country adoption alone to running orphanages in tourist areas to attract donations — 90% of homes being in the top 5 tourist districts. In 2015, Next Generation Nepal (NGN) and UNICEF released statements warning about the increase in child institutionalization. The government of Nepal subsequently passed a directive prohibiting children to cross district borders unless they were with their parents or had government approval. There are still hundreds of children living in orphanages in Nepal today, although the COVID-19 pandemic restricted operational space and allowed local governments to better implement their child protection mandates, contributing to the strengthening of the overall system.

In China, there is also an opaque relationship between trafficking and adoption. It was discovered in 2012 that Americans alone adopted almost 3,000 Chinese children who were taken from their parents and sold into orphanages. As a country that is aware of the existing issue, parents often have to take matters into their own hands to conduct searches because local law enforcement will silence anyone who is publicly discontent. Aside from the financial incentive of orphanage volunteering alone, scammers have even gone as far as to request large sums of money from parents for information on their child’s whereabouts, information that is ultimately fake.

Aside from the vulnerabilities of the children, traffickers also prey on those of their parents. In Haiti particularly, parents placed their children into orphanages after the 2010 earthquake. They were pressured to believe that their children would be better off; they would have a roof over their heads, food and access to education. One woman, struggling to provide for her sons, was approached by Jonathas Vernet who offered to help her. Vernert, previously running the Four Winds Spirit orphanage, was found to have subjected children to cooking, cleaning and abusively harsh discipline. The children did not attend school and lived in distressed conditions, but Vernet justified this by blaming American donors for neglecting to offer sufficient financial support. An estimated $100 million a year is donated to all orphanages in Haiti by churches and nonprofits in the United States for the purpose of providing food, water, medical care and education. However, most of this money is used to drive the continuation of profit from orphanage volunteering and further expand the business. To end the institutionalization of children, Lumos, an to replace orphanages with foster care systems and advocates for local adoption practices. The organization also advises donors to ensure that the projects they are supporting have a sustainable care vision.

Today, orphanage trafficking in Haiti has not changed much. As of 2021, it was estimated that there were 30,000 children in 750 orphanages, with only 35–50 of those being licensed. Despite efforts to develop and regulate the foster care system in Haiti, attempts to combat orphanage tourism have been static as a result of continued high poverty and unemployment rates.

Globally, orphanages have become hubs where child exploitation for profit can thrive, so long as there are still unmonitored donations and vulnerable children. To better curb the proliferation of child trafficking into orphanages, it is recommended that governments prioritize community-based care and better inform philanthropists how their donations to orphanages may be misused. By combating this issue with strengthened child protection systems, increased awareness and the promotion of family-based care over institutionalization, the root causes of this problem can be mitigated and children better protected.

Mira White

Mira is a student at Brown University studying international and public affairs. Passionate about travel and language learning, she is eager to visit each continent to better understand the world and the people across it. In her free time she perfects her French, hoping to someday live in France working as a freelance journalist or in international affairs.