With tensions high domestically and internationally, women both inside and outside of Iran are cynical that things will change.

A mural in support of the Jin, Jiyan, Azadi (Woman, Life, Freedom) movement. Herzi Pinki. CC BY 4.0

For many in Iran, history can be broken up into two epochs: before 1979 and after. Women, in particular, find significance in this demarcation because Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution brought the expansion — and then constriction — of their rights. These tensions surrounding women’s role in Iranian society came to a head in 2022, when the widespread Woman, Life, Freedom movement put them on global display. But the Woman, Life, Freedom movement didn’t spawn out of nowhere, and it’s important to look at its past when considering its future.

Women at the 1979 International Women’s Day protests in Tehran. Mohammad Sayad. CC0

Prior to the Iranian Revolution, women saw their rights and opportunities gradually expand as part of the country’s modernization efforts. The state wanted to Westernize itself, and this manifested in women being mandated (sometimes violently) to not veil themselves, per a 1936 decree. But the revolution saw the nation shirk its Western influences — thanks in large part to women. While some mobilized public demonstrations, others acted as nurses and first responders. Few fought in guerilla conflicts, but many wore hijabs to protest the monarchy's 1936 ban on veils, linking modest dress with the revolution’s vision of a new Iran.

However, after the revolution succeeded and the pro-Western monarchy was overthrown for an Islamist theocracy, women’s roles became more limited. In an interview I conducted with Iranian Circle of Women’s Intercultural Network steering committee member Ruja Kia, she affirmed, “Adding the religious components of private life to the law of the land never makes things easier for women.”

The revolution placed nearly all Iranian state power in the role of “the supreme leader,” where it still remains today. As both a religious and political authority, the first supreme leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, sought to curb women’s post-revolution rights and professional opportunities in favor of a return to traditional domesticity. Further, after revolutionaries associated modesty with the new Islamic Republic, Khomeini mandated women to cover themselves with hijabs. What had once been a symbol of dissent and autonomy became a violently imposed law.

The 1979 hijab mandate notably came under international scrutiny in 2022, following the death of Mahsa Amini. Iran’s Guidance Patrol, or morality police, arrested Amini for an “improper hijab.” She died in their custody three days later — officially of a heart attack but allegedly of police brutality (In our interview, Ruja Kia also noted that Amini was Kurdish, an Iranian ethnic minority that often faces discrimination).

A man protests in support of the Woman, Life, Freedom movement following Amini’s death. Ilias Bartolini. CC BY 2.0

Amini’s death sparked mass protests — not only in Iran but also around the world. Internationally, the rallying cry was “woman, life, freedom,” a translation of the Kurdish feminist slogan “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi.” For its criticisms against the compulsory hijab, the morality police and the Islamic Republic in general, the Woman, Life, Freedom movement has been intensely repressed by Iran’s current supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Iranian security forces have killed more than 500 demonstrators and arrested thousands across the country.

“I say explicitly that these [Woman, Life, Freedom] riots and this insecurity were a design by the US and the occupying, fake Zionist regime [Israel],” Khamenei said in 2022, as reported by Al Jazeera. On a broader scale, Khamenei believes that the hijab is a religious and therefore, moral obligation. He further contended that gender equality is a Western plot designed to weaken Iran: “[The West] feel[s] that [Iran] is progressing towards full-scale power and they can’t tolerate this.” Because of and in spite of Khamenei’s deadly response, the Women, Life, Freedom movement gained international prominence, making the future of women’s rights in Iran an unavoidable and salient issue in the recent election.

Two women attend a Woman, Life, Freedom protest wearing past versions of the Iranian flag. Taymaz Valley. CC BY 2.0

Masoud Pezeshkian, Iran’s newest president, campaigned on a reformist platform, asserting a desire to steer the nation toward greater peace. Now, after taking office in July, he has a chance to do so. For many nations that have tensions with Iran, having the moderate Pezeskian in office is cause for cautious optimism. Inside Iran’s borders, however, women are still reeling from the pushback Woman, Life, Freedom received two years ago and are thus more cynical about the promise of Pezeshkian’s election. “Although we might see more moderate approaches in bigger metropolitan areas, women across the rest of Iran will stay controlled by family customs and norms,” said Ruja Kia.

As the only reformist in a field of six candidates, Pezeshkian’s positions on women’s rights stood out as the most progressive. Frequently invoking his daughter, a chemist, and the memory of his late wife, a gynecologist, he spoke of increasing women’s presence in the professional sector: “A woman is not a servant at home,” Pezeshkian wrote on X.

Regarding the mandatory hijab, Pezeshkian has expressed support for relaxing the mandate: “The behavior of Iranian girls will not change. Just as the previous [1936 laws] could not forcibly remove the hijab from the heads of our women, you cannot force them to wear the hijab by passing a law,” he wrote in another X post. But some, like Kimia Adibi, the President of UC Berkeley’s Iranian Students’ Cultural Organization, believe that Pezeshkian’s words are empty promises. “[Pezeshkian’s] not actually pushing for women’s freedom and change because if he were, he never would’ve been allowed to run,” Adibi said to me. “Anyone who’s an actual radical reformist and believes in women’s freedom and not forcing the mandatory hijab… like, they’re not even going to make it to the candidacy level.”

A woman at a Woman, Life, Freedom protest. Matt Hrkac. CC BY 2.0

Pezeshkian’s parliamentary record shows that he’s supported restrictions on women’s rights in the past, and alongside the posts he made calling for women’s rights, he also posted to X, “All of us move towards dignity and power according [...] to the general policies of the supreme leader.”

For Iranian feminists, the zeitgeist has not shifted. While it’s not impossible, they say, for Pezeshkian to achieve some reform — “little shifts,” as Adibi put it — so long as religion and politics remain married to an ultimate authority who violently rejects gender equality, women’s rights in Iran will not improve much under the new president.

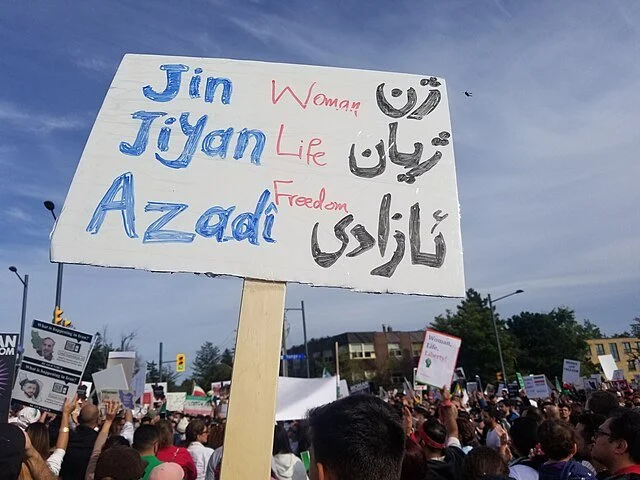

A Woman, Life, Freedom protest sign in Kurdish, English and Persian. Pirehelokan. CC BY 4.0

“I’ll speak for myself,” Adibi said, “but I think most Iranians are not super optimistic about the direction of women’s rights under this president. And they won’t be under the next president, or the next president, under however many presidents until the supreme leader is removed from power.”

When speaking with an admin from the Instagram account @irans.feminist.liberation, I found this feeling re-affirmed. “The future for women and minorities in Iran remains bleak,” she said, “unless there is significant internal pressure for change.

Bella Liu

Bella is a student at UC Berkeley studying English, Media Studies and Journalism. When she’s not writing or working through the books on her nightstand, you can find her painting her nails red, taking digicam photos with her friends or yelling at the TV to make the Dodgers play better.