This organization is working to break down traditional gender barriers to create a communal space for women and men to pray together at Jerusalem’s Western Wall.

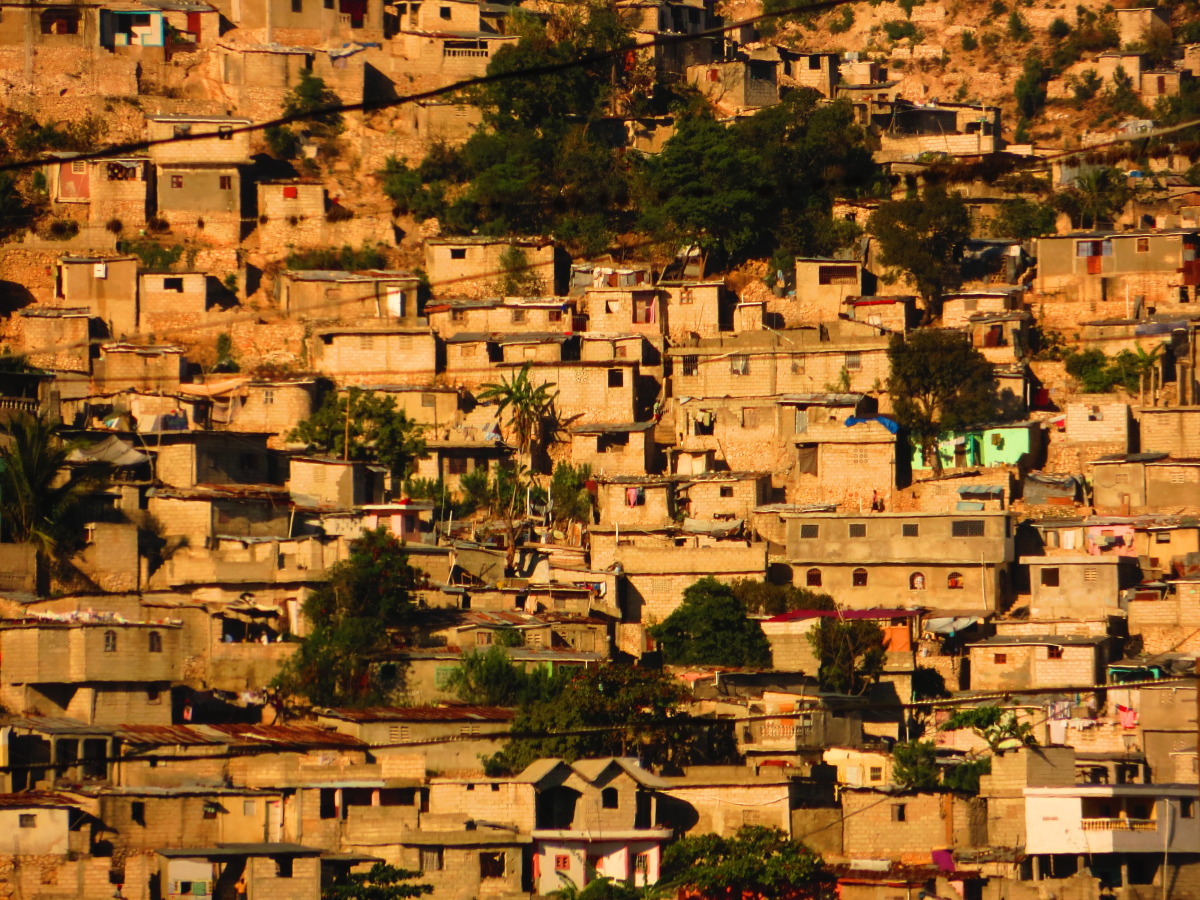

The Western Wall Chris Yunker. CC BY 2.0

Located in Jerusalem’s ancient Old City, the Western Wall marks a central point of religious and spiritual life for millions of Jews, Christians, and Muslims across the world. The wall is believed to mark the only remaining structure of the Temple Mount, the place of the original Temples for the Jewish people, the first of which was destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 BCE and the Second Temple by the Romans in 70 CE.

The Western Wall is also referred to as the Kotel, which is just the Hebrew word for “wall,” and as the Wailing Wall in reference to the manner in which the Jewish people wept at the site during the Roman domination of the Levant. The Wall remains a pivotal place of Jewish history and religious life, with thousands visiting the site daily and leaving prayer notes in the stone crevices.

However, in recent years, the Western Wall has also been at the center of religious debates concerning traditional gender separation. For generations, men and women have visited and prayed at the Western Wall in separate sections, the measures of which are not equal. Stretching just 12 meters in width, the women’s section 36 meters short of-the male side.

Women of the Wall

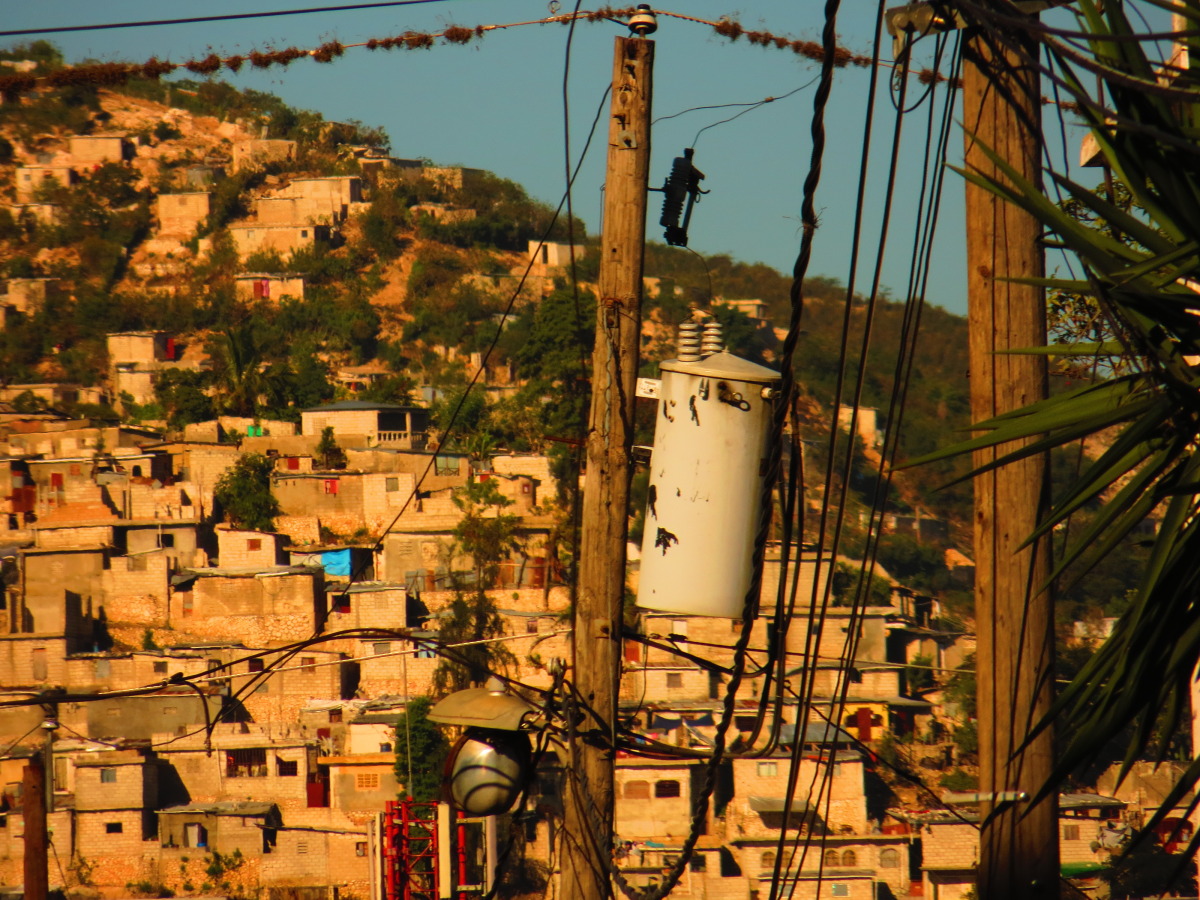

Woman praying at the Wall. it is elisa. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

An organization called Women of the Wall (WOW) is working to increase women’s rights and equality at the Western Wall. The organization’s first meeting occurred in 1988, with 70 Jewish women gathering at the Western Wall to join together in prayer and the Torah reading, where they were met with stark disapproval and verbal assaults from Orthodox Jewish men and women. The event led to WOW’s founding and beginning of its legal fight to empower women to pray at the Western Wall, going against Orthodox norms.

By drawing on systems of social advocacy, education and empowerment WOW is seeking social and legal acceptance of women’s right to wear prayer shawls and to pray and read aloud from the Torah. The group’s mission advocates for women’s right with regards to the four t’s: the right to say a prayer, or Tefillah, the right to wear traditional leather wraps, or Tefillin, that are inscribed with verses from the Torah, the right to wear prayer shawls known as Tallit, and finally the right to read aloud from the Torah.

Along with its advocacy work, WOW regularly gathers together in community at the Western Wall. The group commemorates Rosh Chodesh, a Jewish holiday that marks the new moon at the beginning of each month in the Hebrew calendar, with a collective morning prayer at the Kotel. The holiday is traditionally connected to a celebration of women, with origins dating back to the time of Moses when wives refused to give up their jewelry to build the golden calf, a symbol of sin and idolatry in the Torah.

While these monthly prayer gatherings are a means of celebrating Jewish women’s spiritual life and collective community, they are often met with violence and aggression. The women of WOW are often double searched at the entrance to ensure that they are not smuggling in a Torah, and the group regularly face physical and verbal aggression from the Ultra Orthodox community, an experience that often leaves them with scars and bruises after their day of prayer.

Members of WOW are accustomed to receiving verbal and physical pushback against their cause, and even being spit on by those who view their message as sacrilegious.

A Legal Battle

In 1988 the Ministry of Religion established The Western Wall Foundation, a government body responsible for the care and administration of the Western Wall. Rabbi Shmuel Rabinovitch has served as chairman of the foundation since 1995 and has been known for his efforts to maintain traditional Orthodox customs at the Wall. Rabbi Rabinowitz has criticized WOW’s work in the past, including in 2014 when he spoke out against activists efforts to smuggle a Torah into the women’s section of the Wall.

In spite of women’s legal right to read the Torah, Rabbi Rabinovitch has created regulations that prevent women from bringing in Torahs into the Plaza. Furthermore, Rabbi Rabinovitch’s regulations prevent women from borrowing one of the 200 Torah scrolls kept within the Plaza, which are freely offered to men.

In April 2013, a decision written by Judge Moshe Sobell in the case of Israel Police v. Lesley Sachs, Bonnie Riva Ras, Sylvie Rozenbaum, R. Valerie Stessin, & Sharona Kramer, found that the Israeli Supreme Court’s 2003 case which prohibited women from wearing prayer shawls or reading from the Torah had been misinterpreted, and could not be applied to WOW. Judge Sobell also found that WOW had not endangered the public peace, nor had it violated the Law of Holy Places governing the Western Wall that demands visitors adhere to the local customs. Instead, the ruling dictated that local customs should be determined by the public through nationalistic and pluralistic lenses in addition to the Orthodox one.

The 2013 court decision helped spur ongoing discussions regarding communal prayer spaces at the Wall. In 2013, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu appointed a committee chaired by Natan Sharansky to resolve the issue of communal prayer at the Wall. Sharansky proposed to extend the Western Wall plaza to an area known as Robinson’s Arch in order to provide a pluralistic prayer space for both men and women. The area can accommodate some 450 people, and was seen in many ways as a temporary solution to the question of mixed-gendered prayer.

In January 2016, the Israeli government approved a plan to set up a communal space in which both men and women could pray together. The plan will also give women who want to pray alone but not in accordance with Orthodox rules the option to set up a temporary barrier.

The new area is expected to double the size of the temporary communal prayer area set up in 2013 under Netanyahu, in order to accommodate 1,200 worshippers.

The fight for communal prayer spaces remains a contentious issue between Orthodox and Reformed communities. Although the plan for a pluralistic prayer space was passed by the Knesset, Israel’s legislature, in 2016, as of 2023 the construction and implementation have not yet begun. The issue remains a top priority for members of WOW, who will continue to pray at the Wall’s women’s section until a pluralistic prayer space is constructed.

Get Involved

Other organizations in Israel have come out in support of WOW and embraced a pluralistic perspective towards religious traditions.

Rabbi Danny Rich, a chief executive of Liberal Judaism, celebrated the decision for a communal prayer space as one that represented Judaism’s inclusivity. Through education opportunities, social action campaigns, collaborative interfaith work, and its provision of programming and library of historical archives, Liberal Judaism engages with social justice issues such as climate change, inequality, and poverty.

The Israel Movement for Reform and Progressive Judaism has also praised the women’s representation at the Western Wall, as an exemplification of pluralism and diversity within Jewish community. The Movement seeks to increase the accessibility of progressive and pluralistic Judaism through education programming as well as legislation changes as part of their Israel Religious Action Center (IRAC). Along with their advocacy work, the IRAC offers resources and publications that engage with modern social issues through a progressive and religious lens.

Jessica Blatt

Jessica Blatt graduated from Barnard College with a degree in English. Along with journalism, she is passionate about creative writing and storytelling that inspires readers to engage with the world around them. She hopes to share her love for travel and learning about new cultures through her work.

![[Name withheld] - 20](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/638a651ad5f9324e20972bf2/1670014524351-36X8BO8GD9MSYFTOO5G8/11+syria11youngmen-11aleppo-syria-matador-seo-940x624.jpg)