For the past 600 years, dancers in Papantla, Mexico, have taken to the skies to perform the acrobatic spectacle, the Danza de los Voladores (Dance of the Flyers). Four flyers and one guide dressed in vibrant colors ascend a 20-meter pole, anchored only by a single rope tied to their legs. There, they begin the ritual, flying through the air to ask the sun deity for rain and blessings.

The Nasir ol Molk Mosque in Shiraz, Iran: Islamic architecture is one of the gems of Persian culture, as is its traditional music. Wikimedia Commons

Why Traditional Persian Music Should be Known to the World

Weaving through the rooms of my Brisbane childhood home, carried on the languid, humid, sub-tropical air, was the sound of an Iranian tenor singing 800-year old Persian poems of love. I was in primary school, playing cricket in the streets, riding a BMX with the other boys, stuck at home reading during the heavy rains typical of Queensland.

I had an active, exterior life that was lived on Australian terms, suburban, grounded in English, and easy-going. At the same time, thanks to my mother’s listening habits, courtesy of the tapes and CDs she bought back from trips to Iran, my interior life was being invisibly nourished by something radically other, by a soundscape invoking a world beyond the mundane, and an aesthetic dimension rooted in a sense of transcendence and spiritual longing for the Divine.

I was listening to traditional Persian music (museghi-ye sonnati). This music is the indigenous music of Iran, although it is also performed and maintained in Persian-speaking countries such as Afghanistan and Tajikistan. It has ancient connections to traditional Indian music, as well as more recent ones to Arabic and Turkish modal music.

It is a world-class art that incorporates not only performance but also the science and theory of music and sound. It is, therefore, a body of knowledge, encoding a way of knowing the world and being. The following track is something of what I might have heard in my childhood:

Playing kamancheh, a bowed spike-fiddle, is Kayhān Kalhor, while the singer is the undisputed master of vocals in Persian music, ostād (meaning “maestro”) Mohammad Reza Shajarian. He is singing in the classical vocal style, āvāz, that is the heart of this music.

A non-metric style placing great creative demands on singers, āvāz is improvised along set melodic lines memorised by heart. Without a fixed beat, the vocalist sings with rhythms resembling speech, but speech heightened to an intensified state. This style bears great similarity to the sean-nos style of Ireland, which is also ornamented and non-rhythmic, although sean-nos is totally unaccompanied, unlike Persian āvāz in which the singer is often accompanied by a single stringed instrument.

A somewhat more unorthodox example of āvāz is the following, sung by Alireza Ghorbāni with a synthesised sound underneath his voice rather than any Persian instrument. It creates a hypnotic effect.

Even listeners unfamiliar with Persian music should be able to hear the intensity in the voices of Ghorbāni and Shajarian. Passion is paramount, but passion refined and sublimated so that longing and desire break through ordinary habituated consciousness to point to something unlimited, such as an overwhelming sense of the beyond.

Beyond media contrived images

The traditional poetry and music of Iran aim to create a threshold space, a zone of mystery; a psycho-emotional terrain of suffering, melancholy, death and loss, but also of authentic joy, ecstasy, and hope.

Iranians have tasted much suffering throughout their history, and are wary of being stripped of their identity. Currently, economic sanctions are being re-applied to Iran’s entire civilian population, depriving millions of ordinary people of medicine and essentials.

Traditional Persian music matters in this context of escalating aggression because it is a rich, creative artform, still living and cherished. It binds Iranians in a shared culture that constitutes the authentic life of the people and the country, as opposed to the contrived image of Iran presented in Western media that begins and ends with politics.

This is a thoroughly soulful music, akin not in form but in soulfulness with artists such as John Coltrane or Van Morrison. In the Persian tradition, music is not only for pleasure, but has a transformative purpose. Sound is meant to effect a change in the listener’s consciousness, to bring them into a spiritual state (hāl).

Like other ancient systems, in the Persian tradition the perfection of the formal structures of beautiful music is believed to come from God, as in the Pythagorean phrase, the “music of the spheres.”

Because traditional Persian music has been heavily influenced by Sufism, the mystical aspect of Islam, many rhythmic performances (tasnif, as opposed to āvāz) can (distantly) recall the sounds of Sufi musical ceremonies (sama), with forceful, trance-inducing rhythms. (For instance in this Rumi performance by Alireza Eftekhari).

Even when slow, traditional Persian music is still passionate and ardent in mood, such as this performance of Rumi by Homayoun Shajarian, son of Mohammad-Reza:

A Persian woman playing the Daf, a frame drum, from a painting on the walls of Chehel-sotoon palace, Isfahan, 17th century. Wikimedia Commons

Another link with traditional Celtic music is the grief that runs through Persian music, as can be heard in this instrumental by Kalhor.

Grief and sorrow always work in tandem with joy and ecstasy to create soundscapes that evoke longing and mystery.

Connections with classical poetry

The work of classical poets such as Rumi, Hāfez, Sa’di, Attār, and Omar Khayyām forms the lyrical basis of compositions in traditional Persian music. The rhythmic structure of the music is based on the prosodic system that poetry uses (aruz), a cycle of short and long syllables.

Singers must therefore be masters not only at singing but know Persian poetry and its metrical aspects intimately. Skilled vocalists must be able to interpret poems. Lines or phrases can be extended or repeated, or enhanced with vocal ornaments.

Thus, even for a Persian speaker who knows the poems being sung, Persian music can still reveal new interpretations. Here, for example (from 10:00 to 25:00 mins) is another example of Rumi by M.R. Shajarian:

This is a charity concert from 2003 in Bam, Iran, after a horrendous earthquake destroyed the town. Rumi’s poem is renowned among Persian speakers, but here Mohammad-Reza Shajarian sings it with such passion and emotional intensity that it sounds fresh and revelatory.

“Without everyone else it’s possible,” Rumi says, “Without you life is not liveable.”

While such lines are originally drawn from the tradition of non-religious love poems, in Rumi’s poems the address to the beloved becomes mystical, otherworldly. After a tragedy such as the earthquake, these lyrics can take on special urgency in the present.

When people listen to traditional music, they, like the singers, remain still. Audiences are transfixed and transported.

According to Sufi cosmology, all melodious sounds erupt forth from a world of silence. In Sufism, silence is the condition of the innermost chambers of the human heart, its core (fuad), which is likened to a throne from which the Divine Presence radiates.

Because of this connection with the intelligence and awareness of the heart, many performers of traditional Persian music understand that it must be played through self-forgetting, as beautifully explained here by master Amir Koushkani:

Persian music has roughly twelve modal systems, each known as a dastgah. Each dastgah collects melodic models that are skeletal frameworks upon which performers improvise in the moment. The spiritual aspect of Persian music is made most manifest in this improvisation.

Shajarian has said that the core of traditional music is concentration (tamarkoz), by which he means not only the mind but the whole human awareness. It is a mystical and contemplative music.

The highly melodic nature of Persian music also facilitates expressiveness. Unlike Western classical music, there is very sparing use of harmony. This, and the fact that like other world musical traditions it includes microtonal intervals, may make traditional Persian music odd at first listen for Western audiences.

Solo performances are important to traditional Persian music. In a concert, soloists may be accompanied by another instrument with a series of call-and-response type echoes and recapitulations of melodic phrases.

Similarly, here playing the barbat, a Persian variant of the oud, maestro Hossein Behrooznia shows how percussion and plucked string instruments can forge interwoven melodic structures that create hypnotic soundscapes:

Ancient roots

The roots of traditional Persian music go back to ancient pre-Islamic Persian civilisation, with archaeological evidence of arched harps (a harp in the shape of a bow with a sound box at the lower end), having been used in rituals in Iran as early as 3100BC.

Under the pre-Islamic Parthian (247BC-224AD) and Sasanian (224-651AD) kingdoms, in addition to musical performances on Zoroastrian holy days, music was elevated to an aristocratic art at royal courts.

Centuries after the Sasanians, after the Arab invasion of Iran, Sufi metaphysics brought a new spiritual intelligence to Persian music. Spiritual substance is transmitted through rhythm, metaphors and symbolism, melodies, vocal delivery, instrumentation, composition, and even the etiquette and co-ordination of performances.

A six-string fretted lute, known as a tār. Wikimedia Commons

The main instruments used today go back to ancient Iran. Among others, there is the tār, the six-stringed fretted lute; ney, the vertical reed flute that is important to Rumi’s poetry as a symbol of the human soul crying out in joy or grief; daf, a frame drum important in Sufi ritual; and the setār, a wooden four-stringed lute.

The tār, made of mulberry wood and stretch lambskin, is used to create vibrations that affect the heart and the body’s energies and a central instrument for composition. It is played here by master Hossein Alizadeh and here by master Dariush Talai.

Traditional Persian music not only cross-pollinates with poetry, but with other arts and crafts. At its simplest, this means performing with traditional dress and carpets on stage. In a more symphonic mode of production, an overflow of beauty can be created, such as in this popular and enchanting performance by the group Mahbanu:

They perform in a garden: of course. Iranians love gardens, which have a deeply symbolic and spiritual meaning as a sign or manifestation of Divine splendour. Our word paradise, in fact, comes from the Ancient Persian word, para-daiza, meaning “walled garden”. The walled garden, tended and irrigated, represents in Persian tradition the cultivation of the soul, an inner garden or inner paradise.

The traditional costumes of the band (as with much folk dress around the world) are elegant, colourful, resplendent, yet also modest. The lyrics are tinged with Sufi thought, the poet-lover lamenting the distance of the beloved but proclaiming the sufficiency of staying in unconsumed desire.

As a young boy, I grasped the otherness of Persian music intuitively. I found its timeless spiritual beauty and interiority had no discernible connection with my quotidian, material Australian existence.

Persian music and arts, like other traditional systems, gives a kind of “food” for the soul and spirit that has been destroyed in the West by the dominance of rationalism and capitalism. For 20 years since my boyhood, traditional Persian culture has anchored my identity, healed and replenished my wounded heart, matured my soul, and allowed me to avoid the sense of being without roots in which so many unfortunately find themselves today.

It constitutes a world of beauty and wisdom that is a rich gift to the whole world, standing alongside Irano-Islamic architecture and Iranian garden design.

The problem is the difficulty of sharing this richness with the world. In an age of hypercommunication, why is the beauty of Persian music (or the beauty of traditional arts of many other cultures for that matter) so rarely disseminated? Much of the fault lies with corporate media.

Brilliant women

Mahbanu, who can also be heard here performing a well-known Rumi poem, are mostly female. But readers will very likely not have heard about them, or any of the other rising female musicians and singers of Persian music. According to master-teachers such as Shajarian, there are now often as many female students as male in traditional music schools such as his.

Almost everyone has seen however, through corporate media, the same cliched images of an angry mob of Iranians chanting, soldiers goose-stepping, missile launches, or leaders in rhetorical flight denouncing something. Ordinary Iranian people themselves are almost never heard from directly, and their creativity rarely shown.

The lead singer of the Mahbanu group, Sahar Mohammadi, is a phenomenally talented singer of the āvāz style, as heard here, when she performs in the mournful abu ata mode. She may, indeed, be the best contemporary female vocalist. Yet she is unheard of outside of Iran and small circles of connoisseurs mainly in Europe.

A list of outstanding modern Iranian women poets and musicians requires its own article. Here I will list some of the outstanding singers, very briefly. From an older generation we may mention the master Parisa (discussed below), and Afsaneh Rasaei. Current singers of great talent include, among others, Mahdieh Mohammadkhani, Homa Niknam, Mahileh Moradi, and the mesmerising Sepideh Raissadat.

Finally, one of my favourites is the marvelous Haleh Seifizadeh, whose enchanting singing in a Moscow church suits the space perfectly.

The beloved Shajarian

Tenor Mohammad-Reza Shajarian is by far the most beloved and renowned voice of traditional Persian music. To truly understand his prowess, we can listen to him performing a lyric of the 13th century poet Sa’di:

As heard here, traditional Persian music is at once heavy and serious in its intent, yet expansive and tranquil in its effect. Shajarian begins by singing the word Yār, meaning “beloved”, with an ornamental trill. These trills, called tahrir, are made by rapidly closing the glottis, effectively breaking the notes (the effect is reminiscent of Swiss yodeling).

By singing rapidly and high in the vocal range, a virtuoso display of vocal prowess is created imitating a nightingale, the symbol with whom the poet and singer are most compared in Persian traditional music and poetry. Nightingales symbolise the besotted, suffering, and faithful lover. (For those interested, Homayoun Shajarian, explains the technique in this video).

As with many singers, the great Parisa, heard here in a wonderful concert from pre-revolutionary Iran, learned her command of tahrir partly from Shajarian. With her voice in particular, the similarity to a nightingale’s trilling is clear.

Nourishing hearts and souls

The majority of Iran’s 80 million population are under 30 years of age. Not all are involved in traditional culture. Some prefer to make hip-hop or heavy-metal, or theatre or cinema. Still, there are many young Iranians expressing themselves through poetry (the country’s most important artform) and traditional music.

National and cultural identity for Iranians is marked by a sense of having a tradition, of being rooted in ancient origins, and of carrying something of great cultural significance from past generations, to be preserved for the future as repository of knowledge and wisdom. This precious thing that is handed down persists while political systems change.

Iran’s traditional music carries messages of beauty, joy, sorrow and love from the heart of the Iranian people to the world. These messages are not simply of a national character, but universally human, albeit inflected by Iranian history and mentality.

This is why traditional Persian music should be known to the world. Ever since its melodies first pierced my room in Brisbane, ever since it began to transport me to places of the spirit years ago, I’ve wondered if it could also perhaps nourish the hearts and souls of some of my fellow Australians, across the gulf of language, history, and time.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

RELATED CONTENT:

Musical Styles Worth Exploring in Lusophone Countries

VIDEO: Reinventing Electronic Music With Dubai’s Cellist DJ

VIDEO: Mirage of Persia

DARIUS SEPEHRI

Darius is a Doctoral Candidate for Comparative Literature in the Religion and History of Philosophy at the University of Sydney.

Two capoeiristas in the streets of Brazil. Otubo. CC BY 2.0

5 Latin American Dances

Latin America originated many famous dances, including merengue, bachata, tango, samba and capoeira. Culturally, they represent the heart of Latin America with music and dance styles that are now celebrated throughout the world.

1. Merengue, Dominican Republic:

Merengue dancer. Max Bosio. CC BY 2.0

Merengue is the national dance of the Dominican Republic; however, merengue originated in multiple sites across the Caribbean. In Puerto Rico, Cuban marching bands created the merengue initially called the “upa” in 1842. At this time, local elites considered an African variant of the dance as a “corrupting influence.” Therefore, the government passed laws to fine and imprison those who danced merengue. Forty years later, Puerto Rico’s merengue died out, but Dominican merengue lived on. Merengue has two origin stories circulating in the Dominican Republic. The first story is that enslaved people created the dance as they cut sugar to the beat of drums while dragging one chained leg behind them. The other story is about a hero who returned to his village with a wounded leg after a revolution in the Dominican Republic. Both stories explain the usage of a dragging leg movement used in merengue.

Merengue pairs dance with flirtatious gestures as dancers move in circles. Meanwhile, the music usually consists of accordions, drums and saxophones. Merengue plays an active role in many people’s daily lives; for instance, at social gatherings, celebrations and political campaigning. The dance has migrated to other Latin American countries, such as Venezuela and Colombia, where various forms have emerged.

2. Bachata, Dominican Republic:

A couple dancing street bachata. Fridaycafe. CC BY-SA 2.0

Bachata was born in the Dominican Republic during the dictatorship of Trujillo. Trujillo claimed bachata was a lower art form and altogether banned both the music and the dance. As a result, bachata was only enjoyed in brothels, not helping its status as a respectable dance. Even after Trujillo’s reign, bachata was still frowned upon by society. In the 1960s and 70s, the people considered bachata to be “the poor people’s music.” Now, bachata is accepted and celebrated as hundreds of academics, studios and schools are dedicated to its transmission. There are three primary forms of bachata practiced; the Dominican bachata, bachata moderna and the traditional style. Bachata is a passionate dance between partners characterized by sensual hip movement and a simple eight-step structure. The lyrics of bachata music typically express deep feelings of love, passion, nostalgia, and feature a strong guitar base. Recently, bachata gained popularity because artists like Aventura, Prince Royce and Romeo Santos who turned bachata into one of the most sensual and romantic Latin dances.

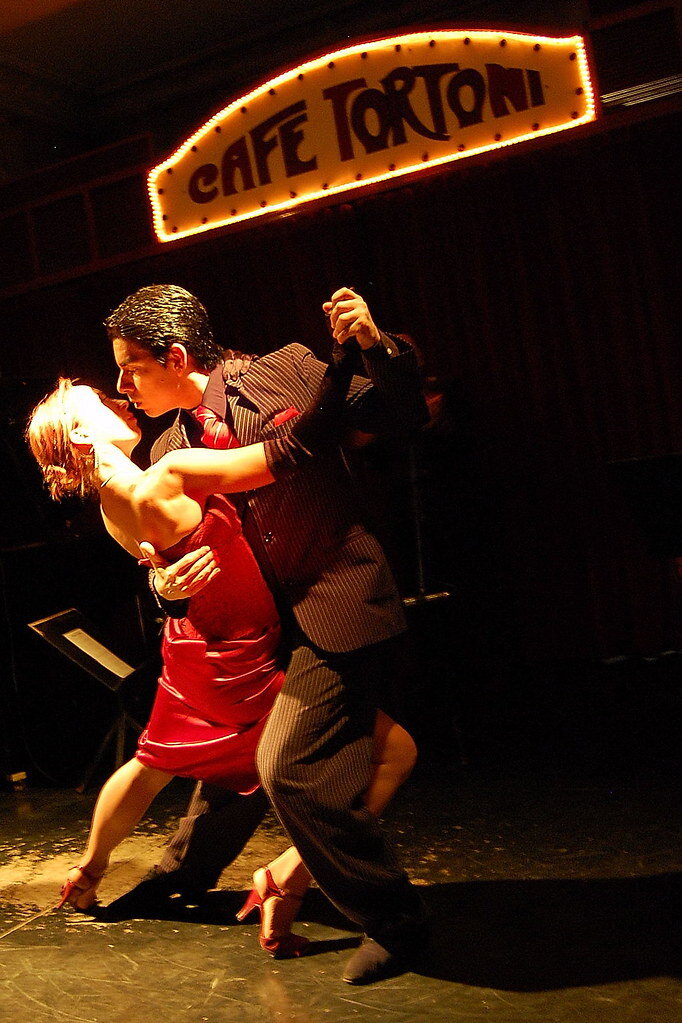

3. Tango, Argentina:

Tango dancers amidst their dance. Armando Maynez. CC BY 2.0

Tango emerged from the immigrant culture on Argentina’s dockside slums; it’s a fusion of New World, African and European dance styles. Specifically, the music is inspired by the African community in Buenos Aires and uses elements from African rhythm, European music and South American songs. In its early years, tango primarily took place in the brothels of Buenos Aires. The steps are considered sexual and aggressive, with music creating feelings of longing and despair. It is said that dancers acted out the relationship of the prostitute and the pimp. In Buenos Aires, the upper-class society formerly considered tango indecent and associated it with violence, illicit sex and the lower class. In 1912, the passage of universal suffrage laws granted the lower class legitimacy, giving tango higher credibility.

Additionally, as tango moved across Europe, the steps simplified and the sensual quality diminished a little. European approval made the tango acceptable to all Argentineans, and by the 1920s, it evolved into a national folk treasure. Argentinian dancers at its peak in the 1940s performed in cabarets, dance salons, social and sports clubs and restaurants. During tango’s golden age, Maria Nieves, a star from the 1980s show Forever Tango, said, “We were swept away by our love for tango. We just loved to go dancing. We didn't go out looking for sex...we didn't care what the man looked like. It was a nice, beautiful, pure group of girls, interested only in the tango.”

4. Samba, Brazil

Samba dancers in Brazil. Sfmission.com. CC BY 2.0

Samba originated in Brazil as a musical genre and dance style. Samba’s roots are in Africa. Brazil’s African descendants brought as slaves from Angola and Congo first influenced and created the dance. Samba was first born in Bahia, a coastal state of Brazil known as “Little Africa.” Some believe the Bahian priestesses would invoke the gods through song and dance. The word “samba” derives from the African Bantu word “semba.” The Kimbundo word means “naval bump” which depicts intimacy and invitation to dance. The word samba is also the infinitive of kusamba, which means to pray or do a favor to the gods through song and dance. Some believe the heart of samba comes from Angola’s traditional semba music, which is about celebrating religious worship through an ancient rhythm. The musical genre combines percussion tempo with sounds of pandeiro, reco reco, tamborim and ciuca. The dance form typically emphasizes the movements of the hip and belly. Samba has become an icon of Brazil’s national identity as a form of cultural expression.

5. Capoeira, Brazil

Capoeira with instruments playing in the background CC BY-SA 2.0

Capoeira isn’t a typical dance; it’s an art form tying fighting, dance, music, ritual and philosophy together to create a unique game called jogo de capoeira. Enslaved Africans brought their traditions from various cultures to South America, including capoeira. It was practiced on plantations as means of breaking the bonds of slavery both physically and mentally. At that time, capoeira was prohibited by the Brazilian Penal Code, because it was considered a social infirmity. The term “the outlaw” became so deeply incorporated with capoeira that the word transformed into a synonym for “bum,” “bandit” and “thief.”

Nevertheless, capoeira persisted from its marginalized identity and became a cultural phenomenon. As a cultural art form, capoeira was a means to ensure African tradition would survive through slavery. Afro-Brazilians still uniquely evolve the practice throughout the years. The music along with capoeira consists of a bateria (orchestra) with three berimbau (stringed bow-like instruments), pandeiros (tambourines), an agogo (bell), a reco-reco (small bamboo instrument) and an atabaque (drum). The dance is like a game that can be playful and cooperative, intense and competitive. The movement is a fluid, swinging stance called “ginga.” Capoeiristas teach to attack and defend from any position with any part of the body to practice adaptability and preparedness for any movements. The underlying principles of capoeira are understanding the complexities of human interaction, being ready for anything, the value of cleverness and the strength of indirect resistance. As its creators were once oppressed, capoeira’s philosophy is rooted in survival at all costs through creative measures.

RELATED CONTENT:

VIDEO: The Band Bringing Venezuela’s Best Dance Party to the World

Kyla Denisevich

Kyla is an upcoming senior at Boston University, and is majoring in Journalism with a minor in Anthropology. She writes articles for the Daily Free Press at BU and a local paper in Malden, Massachusetts called Urban Media Arts. Pursuing journalism is her passion, and she aims to highlight stories from people of all walks of life to encourage productive, educated conversation. In the future, Kyla hopes to create well researched multimedia stories which emphasize under-recognized narratives.

VIDEO: A Diary of Senegal

In a departure from typical travelogues, this video shows a unique picture of Senegal through glimpses into everyday rural life with a focus on the children growing up in this beautiful country. Each clip showcases the diversity in landscape, culture, and lifestyle Senegal’s people experience—all bound together by an enthusiasm for life. After watching this video, you’ll want to dance with the people on screen.

Curves of Iran

“Curves are everywhere in Eastern culture: our writing, our architecture, our instruments, the way we dance; even the tone of our language is curved. The West was built on angles. The East was built on curves.”

The Hawaiian Rain Dancers Who Summon Storms

On the island of Hawaii, the rain dancers of Waimea perform their art for the only audience that matters: their ancestors. When they call for rain and snow, they dance not to entertain, but to feed and nourish their land. Each performance is a physical manifestation of the spiritual world, a chance to connect with the natural land we inhabit. Practicing a centuries-old form of hula rarely seen in public, these dancers carry on generations of tradition with every graceful move and each handmade kapa garment.

Tibet was invaded by China in the 1950s. Tibetan independence is still a fiercely debated topic in Asia and abroad. (WT-en) SONORAMA at English Wikivoyage - Own work. Public Domain.

Masters of Ceremony: Hip-Hop’s Influence in the Tibetan Diaspora

Ask a person for their opinion on rap and they may tell you that it’s all about money and material possessions- they would be right. More precisely, it is all about money and material possessions that the rapper never thought he or she would have when he or she was poor, and the “haters” who want to harm the rapper, emotionally, physically, or both. Rap in America tells the story of social advancement in low-income neighborhoods, where anyone doing anything that might take them to a new landscape or living standard will incur the resentment of their peers. The lyrics often fly over the heads of middle and upper-class listeners, who can reach the same the stature as the rapper they are listening to, but without the same arc. Hip-Hop tends to find its voice among the lower classes, and not just in the US. The genre is finding an audience among Tibetans as well, and they are using the music to tell the story of their own struggles inside and outside of their homeland.

The Tibetan autonomous region lies in the southwest part of China, bordering India, Nepal, and Bhutan. It is considered to be the traditional home of the Tibetan people, though some members of the Tibetan community have also asserted rights to parts of the Qinghai, Sichuan, Yunnan and Gansu Provinces. Tibetans viewed their homeland as an independent country, governed by spiritual and temporal leaders known as Dalai Llamas, but in 1950 the Chinese Communist party asserted its sovereignty over Tibet, sending troops to crush the Tibetan army and annex the land. A failed revolt against the Chinese forces in 1959 prompted the 14th Dalai Lama to flee Tibet and establish a government in India. From there he continued to push for Tibetan independence from China. Even today, Tibet is a very touchy subject in China and one best avoided by foreigners visiting the country.

After the occupation, much of the Tibetan community was scattered, with some remaining in the autonomous region while others spread to neighboring countries or left Asia entirely. As American Hip-Hop became more popular and international it was adopted by the Tibetan community but modified to reflect Tibetan cultural values. In 2009, Swiss-Tibetan rapper Shapaley ’s single “Made in Tibet” called for Tibetans around the world to stay strong and remember where they came from. Shapaley spent his childhood years in Lhasa, an experience that profoundly shaped his views on the condition of Tibet and Tibetan people under the Chinese Communist regime. The song was banned by Chinese authorities. In 2017, female rapper TibChicks won international fame when she released several songs on the internet without the backing of a record label. Singles like “Fearless” reflected a new bolder ideology that is spreading among the Tibetan youth. There is a belief now that anything is possible, and through music, Tibetans are not only preserving their identity but evolving it.

JONATHAN ROBINSON is an intern at CATALYST. He is a travel enthusiast always adding new people, places, experiences to his story. He hopes to use writing as a means to connect with others like himself.

Bear Dance

One of my most vivid memories growing up as young child in Romania is watching loud, drunken bears dancing wildly around my grandparents’ living room. Electrifying, enchanting, and at times also quite scary, the annual “bear dance” was always one of the highlights of our holiday season, especially given the strict era of Communist rule.

Every year, in a handful of towns and villages along the Trotus Valley of Romania, troupes of “dancing bears” — men and women of all ages wearing real bear skins — tour villages and visit people’s homes between Christmas and the start of January. This traditional folk ritual, where raucous packs of bears dance and play music for tips, liquor, and cubes of pig fat, is believed to chase away bad spirits from the previous year.

A troupe of bears performs in central Comăneşti during its annual Bear Parade and competition. The mayor organizes the event and offers a cash prize to the best bear troupe. Comănești, Bacău, Romania

When I was only eight years old, my family left Romania behind, and we became political refugees in Yugoslavia. After initially resettling in Canada, we then moved to New York when I was 16. I later went on to study Economics, Neuroscience, and International Development, and eventually returned overseas when I took up a career in humanitarian aid, often working with displaced populations, much like my family and I once were.

In 2013, I decided quit aid work and fully pursue a career as a photographer. I continued to spend most of my time in areas experiencing social unrest or humanitarian emergencies, but now I had a camera in hand. Last year, however, I took a week to return to Romania and visit my ailing grandmother — and to see the dancing bears again.

A troupe of bears dance through Comăneşti, stopping at homes where they have been invited to perform. Comănești, Bacău, Romania

My mother’s childhood friends introduced me to Dumitru Toloaca and his troupe of men, women and children clad in bearskins. I spent a few freezing days photographing them as they performed in the main square of Comăneşti, and then danced their way into the night, through villages like Asău, on their way to private homes where they had been invited to perform.

It’s not unusual for roads to be blocked by bear troupes towards the end of the year.

Cătălin Apetroaie chats with a young bear and the ‘bear tamer’ seated on his porch. He and the rest of Toloacă’s troupe have just finished performing for Apetroaie’s family.

There were so many times that I wanted to put my camera down, put on a bearskin, and join them. It was magical, like going into a fairy tale.

At first, you can’t see much because it’s so dark. You just hear the crunch of the bear-claw boots on the snow and then, all of a sudden, drumbeats break out and you hear the sound of flutes echoing through the alleyways. Then the dancers pass under a streetlamp, and you see bears caught in a snowstorm!

Toloaca’s troupe of bears dance through the night, making their way to the homes where they’ve been invited to perform. Asău, Bacău, Romania

As a child I remember how beautiful it was to wake up filled with anticipation on a snowy December morning and to hear drumbeats and chanting echoing through the valley. The bear troupes would come door to door and everyone would let them in. They were quite rambunctious, swinging their heads around and causing a mess as the snow on them melted.

Catalin Apetroaie, a bear in Toalaca’s troupe, serves his fellow bears a refueling of pig fat at his home in Laloaia where they have just performed. His wife fills up glasses of homemade palinka liquor.

The origins of Romania’s bear dance date back to the 1930s when the Roma, or gypsies, would descend from the surrounding mountains with bear cubs on leashes, and visit the homes of villagers. My grandmother still recalls how gypsies would be given a tip in exchange for the bear cub walking on the backs of the villagers, said to alleviate back pain.

Once a bear aged, the Roma would then employ it for a different purpose when visiting households — they would set the bear to walk on hot metal sheets, which would cause the bear to “dance” or skitter about on the metal to avoid the burning sensation beneath its feet.

Between visits to houses where they have been invited to perform, Toloaca’s troupe of bears stops at a bar for some rest, drinks and more celebrating. Asău, Bacău, Romania

No one really knows when the Roma began wearing bear skins and imitating their dancing bears, or when ethnic Romanians then adapted the ritual, but the gypsy origins are still clearly discernible in the lyrics sang by the “bear tamer” as well as the more traditional costumes sometimes worn, often complete with black stove grease or soot smeared onto the tamer’s face, to imitate the darker skin of a gypsy.

A troupe of bears performs down the main street in Moinesti, during the town’s annual bear parade. Moinești, Bacău, Romania

Today, the Roma are largely excluded from the tradition of bear dancing. Reasons include widespread discrimination against the Roma, as well as the increased cost of bear skins — as bear hunting in Romania has been strictly regulated for some time now, one skin can fetch up to 2,000 Euros.

A lady bear in Toloaca’s troupe plays with the young son of Catalin Apetroaie, a bear dancer himself, after a performance at his home. The child’s grandmother scurries by while his great-grandmother peers at the bears from inside the house. Asău, Bacău, Romania

In today’s post-communist era, modernization and westernization have created a new generation of youth more interested in video games than folk traditions . Moreover, most young adults move to nearby countries or larger cities, in search of work, leaving the rural areas populated by only the elderly or very young. It’s difficult to find people that will carry on the tradition. Coupled with the increasing financial struggles of rural households — after the the fall of communism, rural areas became poorer while urban ones became wealthier — the bear dance tradition is now at risk of disappearing.

A troupe of bears from Asău village performs in central Comăneşti during the town’s annual Bear Parade and Competition.

Although in the minority, female bears can be found in nearly every troupe. Comănești, Bacău, Romania

So far, Romania’s bear dance has survived largely due to the efforts of local governments who throw parades and competitions to incentivize the organization of bear troupes, as well as to recognize and celebrate the individual efforts of dedicated and passionate troupe leaders like Dumitru Toloaca. Like most of the other troupe leaders in the area, Toloaca grew up with the tradition as a boy and holds it close to his heart.

Dumitru Toloaca embraces his daughter, Roxana, as his troupe dances to the beat of the drummers and the lyrics of his bear tamer. Roxana, an only child, is his only hope for his bear troupe to carry on into the next generation. Asău, Bacău, Romania

About a year ago, at the urging of concerned local governments, UNESCO initiated a process that may result in Romania’s bear dance being included on its official “List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding,” an international measure for the protection of cultural practices that are in danger of disappearing. This process takes at least two years to complete, and acceptance is not guaranteed.

Toloaca’s bears dance and encircle their tamer, Gabriel Hanganu. After winning first place at Comanesti’s annual Bear Parade, Toloaca‘s troupe celebrated in the streets, singing, dancing and toasting with homemade palinka liquor handed out by residents. Asău, Bacău, Romania

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON MAPTIA.

DIANA ZEYNEB ALHINDAWI

Diana is a photographer working internationally on stories about humanitarian, human rights, or cultural issues.

Peculiar travel suggestions are dancing lessons from God.

We should consider every day lost in which we do not dance at least once.

UGANDA: Kids from This Slum Are Dancing Their Way Out of Poverty

There are several aspects of human life I strongly believe unite the world. You don’t need to speak the same language or share the same background to connect on any of these and that’s awesome!

What are they?

Food, science, math, sports, and the most fun… music and dancing. Which is partly why this video is so inspiring and went viral with over 14 million views last year.

Yes, these kids should clearly be onstage with Beyoncé for their incredible dance moves. But that’s not the only reason this video is fantastic.

The kids dancing in this video are known as the Ghetto Kids. They are from the slums in Kampala, Uganda, and thanks to their math teacher Dauda Kavuma they train almost daily to improve their dance techniques and the quality of lives for their families.

The Ghetto Kids dance video has allowed some of the children in this video to afford school supplies, stay in school, and even provide better homes for their families.

Sometimes it doesn’t take much to improve the lives of those living in poverty. In this case— a great teacher and people like you willing to share how incredible these kids truly are can make a huge difference.

Update: The Ghetto Kids are now working on creating high production videos, continuing to dance and perform and most importantly continuing their education, according to BBC. I hope to see these kids onstage with Beyoncé at the next Global Citizen Festival (if it’s okay with their math teacher and parents first).

You can go to TAKE ACTION NOW and help kids get the education they need and deserve.

MEGHAN WERFT

Meghan is a Digital Content Creator at Global Citizen. After studying International Political Economy at the University of Puget Sound she moved to New York. Originally from California she brings her love of yoga, kayaking and burritos to the big city. She is a firm believer that education and awareness on global issues has the power to create a more sustainable, equal world where poverty does not exist.

VIDEO: Bouncing Cats — The Story Of Breakdance Project Uganda

The 2010 documentary "Bouncing Cats" tells the story of Breakdance Project Uganda (BPU). BPU is a nonprofit founded by Abraham "Abramz" Tekya, a break-dancer and AIDS orphan. BPU utilizes break-dancing and hip-hop to promote social change and social responsibility. The nonprofit achieves this by "bringing together people from different social, economical, educational, tribal, and religious backgrounds" through dance. Based in Kampala, Uganda, BPU offers free break-dancing classes and gives lessons in juvenile prisons, local schools, community centers, and orphanages.

LEARN MORE AT BOUNCING CATS