Here are 10 fictional narratives detailing aspects of the immigrant experience from the hilarious to the heart-wrenching and everything in between.

Bookshelves. Hannah Gersen. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Travel has been a popular topic among authors for almost as long as writing has existed. From the heroic tales of Odysseus’ journey first published in Homer’s 7th century BC epic, to the many articles highlighting hidden wonders on this very website, the idea of reading about far away places and getting lost in descriptions of exotic foreignness has always drawn a huge following. The subsection of this genre that focuses on migrant experiences, however, adds a completely unique flavor to these stories of new discovery. Here are 10 books that highlight, among others, themes of cultural assimilation, hardships encountered in completely foreign settings and the balance between wanting a better life and loyalty to one's country.

1. Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi (2020)

After her critically acclaimed debut novel Homegoing, Ghanian-American novelist Yaa Gyasi has finally gifted her readers another emotional rollercoaster in “Transcendent Kingdom”. Her protagonist, Gifty, a whip smart first generation neuroscience candidate at Stanford, finds herself struggling to accommodate her Ghanian mother’s pervasive religious beliefs alongside her scientific research. Maybe more importantly, Gifty is also struggling to find herself, her place in society, her true calling in life and love. “Transcendent Kingdom” is raw, honest and unsparing in its examination of one woman’s journey to self-acceptance.

This debut novel from Queens local Daphne Palasi Andreades is a beautifully lyrical homage to young women of color making their way through the complexities of teenage life in the New York borough. The book follows “girls like Nadira, Gabby, Naz, Trish, Angelique” among others as they face the realities of reconciling their American dreams with histories and cultures rooted in the faraway homelands of their parents. Andreades masterfully balances the day to day of life in Queens while tackling the issues of race, class, identity and cultural marginalization dealt with by brown girls everywhere.

Charles Yu is back with another satirically analogous novel, this time tastefully playing back and forth between Asian-American stereotypes and Hollywood clichés to narrate, literally, the far reaching aspirations of “Generic Asian Man” Willis Wu. Willis feels so much an unremarkable member of Chinatown’s exotic foreign aesthetic, that he can’t even see himself as the main character in his own life. His dreams, on the other hand, have him playing “Kung Fu Guy”, a role achieved only by those lucky enough to claw their way out of Chinatown’s grasp, but one that will force Willis to confront his family’s heritage in the context of a hostile America.

Romance novel fans look no further -- Kasim Ali’s debut novel “Good Intentions” follows the love story between Yasmina and Nur from reckless college parties to the uncertainties of post-graduation adulthood. Both first generation immigrants from Sudan and Pakistan respectively, Yasmina and Nur are navigating the balance between traditional Muslim values and their feelings for each other. While Yasmina, passionate and headstrong, seems to have everything figured out, Nur can’t bring himself to tell his parents about his relationship, even four years in. Comforting and heartbreaking all at the same time, the romance novel is the ultimate homage to young love in vibrant color.

This award-winning novel is Indian-British author Sunjeev Sahota’s second publication, telling the sweeping narrative of four young Indians facing the punishing realities of building a new life in foreign surroundings. Avtar, Randeep, Tochi and Narinder want nothing more than to leave their pasts in the rural Indian villages which they fought so hard to escape, but they have no idea how much hardship still awaits them. Stretching from the most remote corners of Eastern India to the crumbling housing complexes in Sheffield, Sahota shares a story of dreams and ambition, of the ever-pervasive sufferings of generational poverty and inequality and of the sheer strength of the immigrant spirit in the face of seemingly insurmountable difficulty.

A love letter to Khmer teenagers, monks, donut shop owners, badminton players and everyone else in the Cambodian enclave of Stockton, California, Anthony Veasna So’s collection of short stories paint a darkly humorous picture of his community. Each vignette holds up a microscope to a crucial turning point in a young Khmer life, some of which lead their protagonists to long-awaited clarity and relief while others are simply plagued by more questions and emotional instability. So is unrelenting in his study of the good, the bad and the ugly of what it means to be “Cambo” -- what it means to carry the searingly fresh wounds of recent history while chasing success in 21st century America.

Toronto-based author Zalika Reid-Benta’s debut short story collection follows the conflicted Kara Davis who constantly feels as though she is falling between the cracks of her Jamaican ancestry and her Canadian nationality. A coming of age story set against the rich backdrop of Toronto’s Little Jamaica neighborhood, “Frying Plantain” perfectly captures the power of a single moment to completely alter a relationship, an intention and even an entire life. Familial relationships are tested and generations clash over what it means to be a “true Jamaican” while embracing new opportunities, all while being wrapped up in ever-present tensions of being black in a predominantly white country.

Marked by its huge cast of unforgettable characters, “Mama Tandoori” is the heart-warming story of author Ernest van der Kwast’s childhood under the watchful eyes of his austere Dutch father and big-hearted Indian mother. With hilarity around every corner, van der Kwast introduces his heptathlete aunt and Bollywood star uncle amongst a colorful lineup of relatives, each adding spices of their own to the recipe of his youth. It is his mother, however, the talented bargainer and ever tenacious Veena van der Kwast, who lies at the center of this novel and breathes life into this moving portrait of familial love.

Siri Ranva Hjelm Jacobsen’s critically acclaimed debut novel approaches the immigrant story from an exhilaratingly new perspective. Island follows a young woman completely removed from her ancestral heritage in the Faroe Islands despite having called it home her whole life. When she is called back by family, she journeys to the rocky shores of the northern archipelago to discover stories about her ancestors that will change the way she sees herself forever. An incredible tale of perseverance and cultural discovery, “Island” explores the complex definition of “home” to those who have more than one.

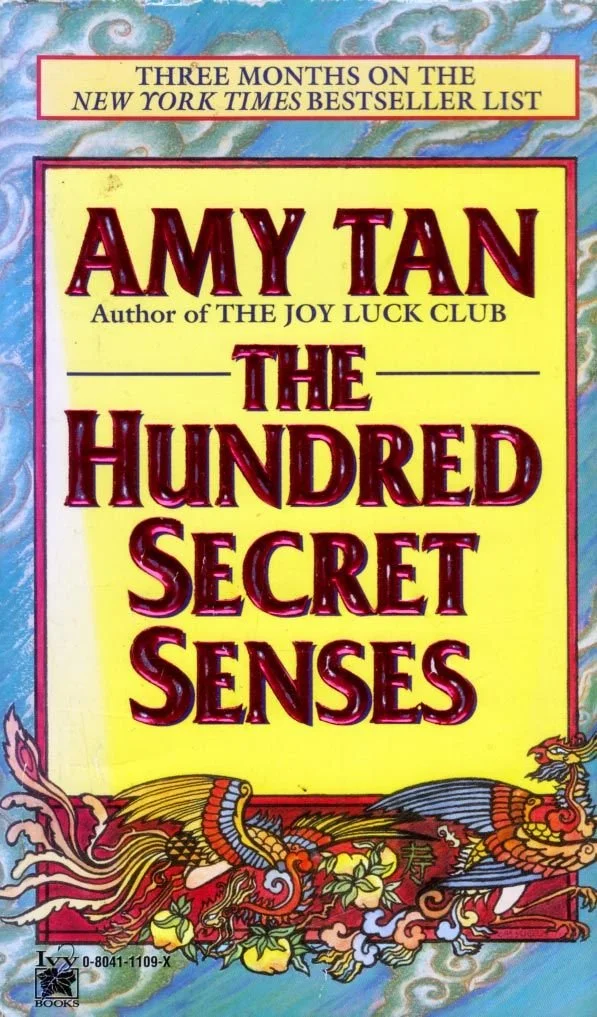

This final one is an oldie but a goodie -- Chinese American author Amy Tan is most well-known for her novel “The Joy Luck Club”, and this novel follows proudly in its footsteps, touching on similar aspects of the Chinese-American immigrant experience, while introducing a refreshing dose of Chinese mysticism and ghostly folklore for good measure. The Hundred Secret Senses follows half-sisters Olivia and Kwan, the former desperately trying to find her place at the intersection of her mixed heritage, and the latter perfectly content in her ability to communicate with the departed souls of those she knew in past lives. Tan weaves a heart-wrenching narrative of love and loss that carries readers from the sunny shores of San Francisco to the bloody terrors of Manchu China, honoring the bonds of familial loyalty and the ties of tradition the whole way through.

Tanaya Vohra

Tanaya is an undergraduate student pursuing a major in Public Health at the University of Chicago. She's lived in Asia, Europe and North America and wants to share her love of travel and exploring new cultures through her writing.