150 years ago, Argentina’s African population was deliberately decimated. Today, the few Afro-Argentines remaining reckon with a trau

Read MoreSri Lankan Journalists Revive the #MeToo Movement

Female journalists in Sri Lanka have united under the #MeToo movement to foster change within the newsroom.

An overhead view of Colombo, Sri Lanka. Jalitha Hewage. Unsplash.

The Sri Lankan government has called for an investigation of several media outlets following allegations of sexual harassment from female journalists. This resurgence of the #MeToo movement was sparked on June 18 when Sri Lankan journalist Sarah Kellapatha spoke up on Twitter about her experience with a male colleague who threatened to rape her during her time at a publication from 2010-2017.

Encouraged by Kellapatha’s story, several other female journalists began to speak out about their own experiences with sexual harassment in the workplace. For example, Sahla Ilham spoke out about being sexually abused by an editor who pressured her family to remain silent. Another who shared their experience was Jordana Narin, who was harassed by a senior colleague until he was forced to resign by the chief editor.

The Sri Lankan government appears to be taking these allegations seriously, as the Minister of Mass Media, Keheliya Rambukwella, asked the Government Information Department to further investigate the claims to help ensure that female journalists feel safe at work.

Currently, the only type of law that Sri Lanka has to address sexual harassment is a criminal law, which would result in imprisonment of up to five years, or a mere fine, for those found guilty. However, according to human rights lawyer Ermiza Tegal, the problem is that the criminal law is rarely used and victims are often undermined and invalidated.

This recent movement shares its roots with the global #MeToo campaign which started back in 2017 following numerous sexual assault allegations against Harvey Weinstein. The movement fostered awareness of sexual abuse, as well as a safe space for victims to speak about their experiences. Similarly, the journalists who have come forward in Sri Lanka have shared their own experiences, many of them from different news publications, in hopes of fostering change and reform within newsrooms.

Zara Irshad

Zara is a third year Communication student at the University of California, San Diego. Her passion for journalism comes from her love of storytelling and desire to learn about others. In addition to writing at CATALYST, she is an Opinion Writer for the UCSD Guardian, which allows her to incorporate various perspectives into her work.

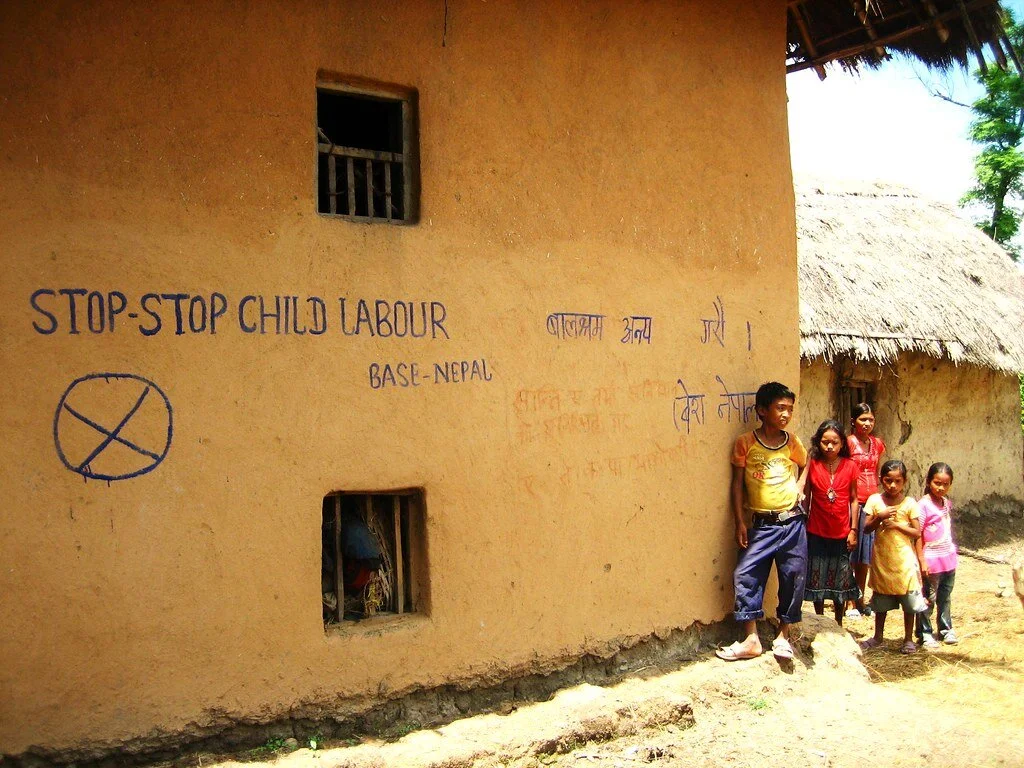

COVID-19 Has Fueled Child Labor in Nepal

With the closing of schools due to COVID-19 and insufficient government aid, children in Nepal are being pushed into dangerous labor.

Stop Child Labor Graffiti in Kothari. The Advocacy Project. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected all aspects of life in Nepal, including education, government assistance, employment and domestic life. Due to adults losing their jobs and income, the rising illness and death rates among caregivers, and even more lockdowns, children are being forced into exploitative labor so they can provide for their families.

The second wave of COVID-19 cases in Nepal continues to put children at risk of child labor. Many children feel that they have no choice in the matter—they work long, grueling hours to help their families survive and provide food.

In Nepal, children work at places like brick kilns, carpet factories and in construction, or as carpenters or vendors selling various items. Some children carry heavy bags at mining sites or crush ore with hammers, all while breathing in dust and fumes from machines and acquiring injuries from sharp objects or particles.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 25 Nepali children between ages 8 and 16, and nearly all of them said that the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative effect on their family income. According to this report, one-third of the children interviewed worked at least 12 hours per day, and some even worked seven days per week. Among the reported side-effects of working long hours, children listed fatigue, dizziness and muscle pain. In addition, many children described hazardous working conditions; many have experienced violence, harassment and pay theft.

A majority of children interviewed also reported that they made less than Nepali minimum wage for their work, which is 517 rupees per day ($4.44 in U.S. dollars). Some children said their employers paid their parents based on a piece rate instead of paying them directly.

Nutrition education seminar in Bandarkharka, Nepal. Bread for the World. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

One of the biggest factors contributing to the rise in child labor is the lack of access to education due to COVID-19. In Nepal, school closures began on March 18, 2020, which affected more than 8 million students. A majority of Nepali students were unable to learn online as well, leaving them without education for over a year. In that education gap, children were often forced to work for their families.

Although most schools reopened in Nepal in January and February of 2021, some children continued to work because their families still needed their child’s income to prevent going into debt. However, in April 2021, schools closed again due to a second wave of COVID-19, and children were put back to work.

Several of Nepal’s neighboring countries, including Bangladesh, India and Pakistan, have expanded cash allowances in order to cover more families. However, Nepal has not yet taken this step. Nepal needs to expand cash allowances so children can be taken out of dangerous labor and put back into school, as well as to enable families to maintain adequate standards of living without relying on child labor.

TO GET INVOLVED

To aid in the global fight against child labor, volunteer with Global March Against Child Labor, a wide network of organizations that work together to eliminate and prevent all forms of child labor through volunteering, fundraising and donating. Love 146, an international human rights NGO working to end child trafficking and exploitation, also provides many ways for people to help. Among many opportunities to help, Love 146 encourages people to get active and start a workout or host a 5k to help raise funds for their work.

To learn more about child labor and find more ways to take action, visit UNICEF’s page on global child labor.

Isabelle Durso

Isabelle is an undergraduate student at Boston University currently on campus in Boston. She is double majoring in Journalism and Film & Television, and she is interested in being a travel writer and writing human-interest stories around the world. Isabelle loves to explore and experience new cultures, and she hopes to share other people's stories through her writing. In the future, she intends to keep writing journalistic articles as well as creative screenplays.

By Refusing an Apology to Algeria, France Shows Colonialism is Far from Over

Algerian architecture reflects continued French influence post-decolonization. mariusz kluzniak. CC BY-NC-NC 2.0.

French President Emmanuel Macron announced on Jan. 20 that he has ruled out issuing an official apology to the country of Algeria for past colonial abuses. This follows 59 years of tense relations between the two nations after the conclusion of the Algerian War in 1962, which marked the end of official French colonialism in the North African country.

The announcement comes as a result of a highly anticipated report on the matter of French-Algerian relations commissioned by Macron in 2020. Rather than a formal apology, the report recommends a “memories and truth” commission to review French colonialism in Algeria. Macron committed to setting up the commission in a statement.

The French occupation of Algeria began with an invasion in 1830, and lasted up until 1962 with the end of the Algerian War, which led to independence. During the 132 years of colonial rule, the French committed a number of atrocities against Algerians, including the massacre of an estimated 500,000 to 1 million Algerians throughout the first three decades of conquest, the forced deportation of native Algerian groups and the use of systematic torture against Algerians during the country’s war for independence.

Since Algeria gained independence, the French government has largely remained silent in regard to the atrocities inflicted during the colonial era. In fact, Macron was the first French president to acknowledge the use of torture during the war for independence when he did so in 2018. Macron has since gone on to demand further accountability, including calls for all archives detailing the disappearance of Algerians during the war. However, the Jan. 20 announcement signals that an official apology remains out of the realm of possibilities for the time being.

Decolonization Efforts Remain a Global Necessity

Protesters marching in Philadelphia in support of Puerto Rican independence in 2018. Joe Piette. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Macron’s announcement is the latest reminder of the continued stains of colonialism which remain in the 21st century. While many former colonial powers like France have largely dismantled their empires and relinquished control to local populations, colonialism and the occupation of Indgenous lands still persists to this day around the world.

Both France and the United Kingdom notably retain overseas territories which are remnants of the heights of their empires. France retains varying administrative control in 11 regions outside of Europe, with a combined population of nearly 2.8 million. Conversely, the British control 14 territories which do not form a part of the United Kingdom itself or its European crown dependencies, representing a combined population of approximately 250,000.

Colonialism, however, is by no means limited to European powers, nor is the process itself a relic of the past. The United States, a country whose foundation is rooted in settler colonialism, retains control over five inhabited territories spread across the Pacific and Atlantic oceans which have a combined population of just over 3.5 million, all of whom are ineligible to vote in federal elections. Likewise, Hawaii’s inclusion in the United States as a state is a result of colonialism in the region where the U.S. systematically undermined native rule throughout the 1800s.

Japan, a country which saw the height of its empire come to an end during World War II, retains control over Hokkaido and Okinawa, two islands with distinct Indigenous populations which have both seen independence movements throughout their time with the country.

China is an example of contemporary colonialism: while not specifically setting up colonies in overseas regions, the country invests billions of dollars in projects to develop African nations on largely unfavorable terms, creates artificial islands in the South China Sea to exercise dominance in the region, and continues to squash independence movements in Tibet and Hong Kong.

While movements for independence, apologies and reparations exist to varying extents in all of these regions, the scars of colonialism persist to this day and remain a contemporary issue unlikely to be resolved in the near future.

Jacob Sutherland

Jacob is a recent graduate from the University of California San Diego where he majored in Political Science and minored in Spanish Language Studies. He previously served as the News Editor for The UCSD Guardian, and hopes to shed light on social justice issues in his work.

An anti-homophobia protest in Russia. Marco Fieber. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Rainbow Railroad Gives Queer Refugees Hope

For over a year, Ray Reynolds slept in a hearse. Working at a funeral home in Montego Bay, Jamaica, he spent his life hiding from homophobic mobs threatening to torture and kill him. “Even though I worked at the funeral home, people still called that place and threatened me. ‘Oh, batty bwoy (a derogatory slur) I know where you is. When I’m coming for you, I’m coming with a tanka (tanker truck with bombs) to burn you out.’” The best hiding place he could find was a hearse; they would never expect to find him there. But Ray knew that if he stayed in Jamaica much longer, he would soon find himself in a coffin six feet underground.

He contacted Rainbow Railroad, and soon, they provided him transport to Spain, where he currently lives. Spain offered a starkly different environment for a gay man like Ray. “I’m free to walk. I’m free to be who I am. I’m free to be what I am.” Along with this newfound freedom, Ray can now experience aspects of queer life strictly forbidden in Jamaica. “I see drag queens, gay people, trans people—everyone together—just having a drink at the bar. Nobody cares!”

Ray is one of more than 800 individuals from 38 different countries to receive assistance from Rainbow Railroad. Founded in 2006, the Toronto-based charity helps LGBTQ+ people escape violence and persecution in their home countries. After reviewing thousands of applications for assistance, Rainbow Railroad has built a worldwide network to lend aid to queer people in need and contribute to LGBTQ+ activist organizations abroad.

Much of its work has focused on Jamaica. In 2006, Time magazine named the Caribbean country “the most homophobic place on earth.” Buggery and anti-sodomy laws that criminalize homosexual intimacy are still on the books. Though they are rarely enforced, these laws buttress Jamaican society’s systematic marginalization of queer individuals. LGBTQ+ individuals face mob violence and constant death threats, many coming from the police force. To escape persecution, they travel from town to town, rarely able to settle in one place and hold a steady job. This, coupled with the expulsion from families that many queer Jamaicans face, has driven many to homelessness. Forced to live away from virulent homophobia, many live in sewers.

40% of the requests Rainbow Railroad receives originate in Jamaica; 300 individuals have been relocated in the past two years. Activist groups on the ground have proven invaluable for the mission of Rainbow Railroad. Upon receiving a request for aid, the person’s identity must be verified and aid given in the requisite areas, including everything from plane tickets and hotel stays to housing assistance and legal representation in the refugee application process.

This process can take up to a year, and the average cost per person is $7,500. Surprisingly, Rainbow Railroad receives no money from the Canadian government, relying instead on private donors. Some donors make contributions in the thousands, but others make small donations through the website or become monthly donors.

The charity first received widespread attention in 2017 when it was one of the first international organizations to take action against the anti-LGBTQ+ purge in Chechnya. Led by Ramzan Kadyrov, the police, military and other state actors began capturing gay men at random and transporting them to detention facilities where they were tortured, raped and sometimes killed. Working with the Russian LGBT Network, Rainbow Railroad helped locate individuals in need and co-funded safe houses where queer individuals could live safely while the logistics of escape were handled. To date, 70 individuals from Chechnya, the Caucasus and Russia have been relocated thanks to Rainbow Railroad.

The charity’s work will become all the more necessary in the coming years. Communications director Andrea Houston notes that the amount of requests has been steadily increasing year after year as populism and authoritarianism flourish worldwide. “Unfortunately,” Houston said, “populism seems to be a winning political strategy right now, and the ones who receive the short end of the stick are marginalized people.”

Simultaneously, the COVID-19 pandemic has upended the lives of countless queer individuals. Bans on travel stranded queer refugees in their home countries. Lockdown measures gave police the license to target queer people and punish them unequally and disproportionately for lockdown violations. The growth of the state in many nations has allowed homophobia to become more embedded and systemic. For the time being, Rainbow Railroad will have to run nonstop in the fight against discrimination.

Michael McCarthy

is an undergraduate student at Haverford College, dodging the pandemic by taking a gap year. He writes in a variety of genres, and his time in high school debate renders political writing an inevitable fascination. Writing at Catalyst and the Bi-Co News, a student-run newspaper, provides an outlet for this passion. In the future, he intends to keep writing in mediums both informative and creative.

Ongoing protests in Nigeria. Tobi Ishannakie. Unsplash.

#ENDSARS: Nigerians Declare Partial Victory in Fight Against Police Brutality

Since the beginning of October, the people of Nigeria have been campaigning and protesting to disband a police force that has been intruding upon their livelihoods with violence and surveillance: the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS). This police unit has been present in Nigeria for almost four decades, and it has only increased in power since its formation. The group was initially founded with the intention of fighting violent crime, including banditry and kidnapping, but now the police force has been accused of extreme profiling through aggressive targeting, especially of young Nigerian men.

Protester encouraging peace. Tobi Ishannakie. Unsplash.

Beginning in 1984, this police force has only increased its power, and the young people of Nigeria have taken to social media to spread this information. With the hashtag #ENDSARS, young Nigerians revealed the problems they face in being subject to an unchecked police force. In addition to the social media campaigns, the extent of SARS’ crimes has brought this issue to the international forefront. The people of Nigeria have made it apparent that they live in fear of this violent police force, and they refuse to be held hostage by them. Amnesty International has backed the Nigerian people’s claims against SARS of extortion, brutality and torture.

These protests come in the wake of over 80 violations of the 2017 Anti-Torture Act passed by the Nigerian government. Amnesty International did an internal study regarding these violations and found that there were little to no repercussions for the officers involved despite overwhelming physical evidence of scars, bruises and dried blood on victims’ bodies. In the same report, they found that many individuals were subject to beatings with weapons like sticks and machetes and were also denied medical care.

Nigerian private police officers. Iyinoluwa John Onaeko. Unsplash.

As mentioned, young men were most frequently subjected to discrimination and mistreatment by SARS. Amnesty International found that those most at risk of arrest, torture and extortion are between the ages of 17 and 30 with common accusations of being internet fraudsters or armed robbers. In terms of physical profiling, young men with dreadlocks, ripped jeans, tattoos, flashy cars or expensive gadgets are frequently targeted by SARS.

Masked protester among other protesters. Tobi Oshinnaike. Unsplash.

Now, as protests have continued, the protesters themselves are being targeted by police. In Edo state, police accused people "posing" as protesters of looting weapons and torching police buildings. As protests grow bigger and escalate in force, military presence has increased in protest areas and prisoners have escaped.

Although the government agreed to disband the unit and dissolved it on Oct. 11 with the intention of retraining the officers, protests have transitioned into calls for wider reforms. The Nigerian people see the government’s plan to retrain officers as a temporary solution to a greater problem. Protesters have been gaining mass support on social media as they use the hashtags #EndBadGovernance, #BetterNigeria and #FixNigeriaNow. The movement has transformed into a greater call for peace and a Nigeria that is safe for all.

Renee Richardson

is currently an English student at The University of Georgia. She lives in Ellijay, Georgia, a small mountain town in the middle of Appalachia. A passionate writer, she is inspired often by her hikes along the Appalachian trail and her efforts to fight for equality across all spectrums. She hopes to further her passion as a writer into a flourishing career that positively impacts others.

Students Call for a Democratic Revolution in Thailand

2020 seems to be the year when students across the globe take part in changing their societies, no matter the cost.

Student protesters. Prachatai. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

In Thailand, student-run organizations have led the march that grew to be an all-out revolution in the busy streets of Bangkok. Thousands of protesters have congregated in the crowded commercial center, Ratchaprasong, chanting for the Thai government to listen to their demands. Protesters call for the removal of Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha, the reduction of the monarchy’s budget so the king’s funds would be separated from crown assets, and the abolition of the strict lese majeste laws which ban the voicing of criticisms against the king.

The unrest began in 2019 when the government banned the most vocal party opposing the power of Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha. Thai citizens are calling for his removal due to the potentially corrupt manner in which he came to power. In 2014 it is said that Prayut staged a coup that shifted his position from army chief to prime minister. The monarchy endorsed his premiership in 2019, allowing him to stay in power after elections which were controversially deemed “fair.”

The Grand Palace in Bangkok. Tom Eversley. CC0

The protests were put on hold through the early part of the year due to COVID-19, but are now growing at a rapid rate. In early October, the government accused protesters of obstructing Queen Suthida’s motorcade during a mass gathering at the Government House to demand the removal of Prayut. Despite the government’s imposition of emergency measures such as banning the gatherings of five or more people, forbidding the publication of news that could “harm national security” and deploying 15,000 police officers to quell the protesters, tens of thousands continually show up to stand for their rights.

Woman waving the Thai flag. The Global Panorama. CC BY-SA 2.0

According to Human Rights Watch, the new emergency measures are allowing officials to keep protesters for up to 30 days without bail or access to lawyers and family members. Human Rights Watch’s deputy director of the Asia Division, Phil Robertson, stated that, “Rights to freedom of speech and holding peaceful public assemblies are on the chopping block from a government that is now showing its truly dictatorial nature.”

University students seem to be at the core of the current demonstrations. The Free Youth Movement was behind the first major protest back in July, inspiring a group from Thammasat University to establish the United Front of Thammasat. Even high school students have joined the fray, identifying as the Bad Student Movement, as they call for education reform. Most of these kids are in their twenties, but they have attracted the attention and support of human rights leaders and lawyers like Arnon Nampa, who was arrested in October along with prominent youth leaders.

Student protesters. Prachatai. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Panupon Jadnok, a teenage protest leader, led a passionate speech during a rally:

“Like dogs cornered, we are fighting till our deaths. We won't fall back. We won't run away. We won't go anywhere.”

Raising their hands in the iconic three-finger salute made popular by ”The Hunger Games,” protesters are shouting in the streets for the police to “release [their] friends” and to stop being “slaves of dictatorship.” They will continue to fight for what they believe is right until all of their demands have been met and their friends and country are free.

Yuliana Rocio

is currently a Literature/Writing major at the University of California San Diego. Yuliana likes to think of herself as a lover of words and a student of the world. She loves to read, swim, and paint in her free time. She spent her youth as part of a travel-loving family and has grown up seeking adventure. She hopes to develop her writing skills, creating work that reflects her voice and her fierce passion for activism.

Myanmar Government Blocks Website Exposing Military Corruption

The website for Justice for Myanmar, which is dedicated to exposing military corruption, was blocked by the country’s government for spreading fake news. Over 200 websites have been blocked in the past year.

Screenshot of the Justice for Myanmar homepage.

On Aug. 27, all mobile operators and service providers in Myanmar received a directive from the government to block the Justice for Myanmar website for purportedly spreading fake news. Justice for Myanmar was launched on April 28 by an anonymous group of activists aiming to expose military corruption and advocate for federal democracy and peace. Campaigning for Myanmar’s Nov. 8 general elections began a week after the shutdown, raising concerns that the government was attempting to silence scrutiny and criticism of the elections.

In May, Justice for Myanmar exposed that two top government officials were also directors of Myanmar Economic Holdings Company Limited, a military-owned company, leading to both officials’ resignations from its board. More recently, Justice for Myanmar revealed that a construction company under contract for the government has ties to Lt. Gen. Soe Htut. The site also published allegations that a medical company offering Food and Drug Administration approvals is owned by the family of Sr. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing.

The military controlled Myanmar for decades, until it was replaced by a civilian government in 2011. The current government is headed by Aung San Suu Kyi of the National League for Democracy (NLD), who serves as State Counsellor. She led the NLD to victory in 2015 during Myanmar’s first openly contested election in 25 years. Despite having a democratic ruler, Myanmar is not free from military rule. A 2008 constitutional provision still guarantees the military seats in parliament. One-quarter of parliamentary seats are held by the military, which also controls the country’s defense, border affairs and home affairs ministries.

Aung San Suu Kyi, once regarded as a prime example of a democratic leader, has been the target of international criticism in recent years for her handling of the Rohingya crisis and her persecution of media and activist groups.

In the past year, Aung San Suu Kyi’s government has blocked over 200 websites for allegedly spreading fake news, using Section 77 of the Telecommunications Law. The section allows action to stop the spread of misinformation. Myanmar’s government received criticism earlier this year for limiting press freedom and the flow of information during the pandemic by blocking news sites. The government also imposed an internet blackout in nine townships in the Rakhine and Chin states and in April 2020 ordered a mass blocking of the websites of ethnic media organizations. These actions, as well as the shutdown of the Justice for Myanmar website just a week before campaigning for the general elections began, have been causes for concern from the media, community organizations and rights groups.

Yadanar Maung, a Justice for Myanmar spokesperson, said in a recent press release that the group condemns “the Myanmar government’s attack on our right to freedom of expression and the people of Myanmar's right to information.” Telenor Myanmar, one of the service providers that received the directive to block the Justice for Myanmar site, has opened communication with the government to protest the blocking. A statement on Telenor Myanmar’s website urges the government “to increase transparency for the public” and asserts that the government’s directive does not respect the rights to freedom of expression or access to information.

Many groups and individuals, including James Rodehaver of the U.N. Human Rights Office, have called for reform of the Telecommunications Law.

Rachel Lynch

is a student at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY currently taking a semester off. She plans to study Writing and Child Development. Rachel loves to travel and is inspired by the places she’s been and everywhere she wants to go. She hopes to educate people on social justice issues and the history and culture of travel destinations through her writing.

Domestic worker Hellina Desta migrated from Ethiopia to work in Beirut in 2008. UN Women/ Joe Saade. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Ethiopian Migrant Workers Left More Vulnerable After Devastating Explosion in Beirut

On Aug. 4, two massive explosions in Beirut, the capital of Lebanon, sent a shock wave that destroyed many neighborhoods, killed more than 200 people, injured 6,000 and left approximately 250,000 homeless. The tragedy struck a country that is already suffering from a major economic crisis, an increase in COVID-19 cases, and the corruption and negligence of the Lebanese government—corruption which led to the deadly explosion. Reports emerged that the government knew about the over 3,000 tons of ammonium nitrate, which is used to build bombs, and left it unattended and unsecured for six years.

As the Lebanese people’s anger boiled over, protests calling for an end to the political elite erupted, leading to the resignation of the majority of the Lebanese government. According to The Wall Street Journal, on Aug. 10 Prime Minister Hassan Diab addressed the nation in a televised address: “I set out to combat corruption, but I discovered that corruption is bigger than the state. I declare today the resignation of this government. God bless Lebanon.”

But according to Foreign Policy, “the public is unlikely to be appeased by the resignation of Diab’s government” as “the rest of the country’s political elites, the sectarian warlords of the civil war era and their descendants, clinging to positions of privilege, are still busy looking for scapegoats.” As the public continues to fight for the fall of the regime, it is hoped that not only will the Lebanese benefit, but so too will the migrant workers whose plight worsens as crises continue to befall the country.

According to The New Arab, “around 250,000 migrants work as housekeepers, nannies and carers in Lebanese homes.” Most of the workers are women, many of whom immigrated from Ethiopia and the Philippines, according to The Associated Press. The migrant workers do not have labor law protections as they were brought in through the kafala system, an exploitative and abusive sponsorship system used in Bahrain, Kuwait, Lebanon, Qatar, Oman, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. The migrant workers are vulnerable to exploitation as the countries that practice the kafala system offer little to no protection for migrant workers—their right to work and legal presence is entirely dependent on their employer. The migration sponsorship system “increases their risk of suffering labor exploitation, forced labor and trafficking, and leaves them with little prospect of obtaining redress,” according to Amnesty International.

The ongoing economic crisis in Lebanon, along with the spike in COVID-19 cases, has made an already dire situation worse for migrant workers. According to Amnesty International, “many have reported that the value of their salaries has decreased by around a third because of the currency crash.” Their salaries were already as little as $150 per month before the severe economic crisis and pandemic, according to France 24. In June, BBC reported that more than 100 Ethiopian migrant domestic workers were fired and left homeless outside their country’s consulate in Beirut after their employers claimed they could no longer afford to pay their maids.

Now, the explosions have left the domestic workers even more vulnerable. CNN reported, “In the aftermath, rights groups are warning that this vulnerable group is facing dire situations as many of them are stranded in the country and unable to go home.” Activists like Farah Salka of Lebanon’s Anti-Racism Movement are fighting for the migrant workers’ rights. Salka told CNN, “They are running from one escalating situation to the other and it is an endless stream of trauma. They have faced COVID, economic crisis, airport closure, quarantine restrictions in often hostile conditions and they want to go home.”

Finding a way home is proving difficult for the Ethiopian migrants. According to Middle East Eye, “Ethiopia has tripled the price of repatriation for its citizens in Lebanon to $1,450, including flights and mandatory quarantine, further prohibiting the return of dozens of women stranded and destitute outside its Beirut consulate.” This is approximately a $900 increase from a May 21 article from Quartz Africa which reported, “Ethiopia’s consulate had collected $550 registration fees for the repatriation flights.”

People on social media are calling for better treatment of migrant workers in Lebanon after footage showed an Ethiopian migrant worker saving a young child from shattered glass as the second explosion erupted in the capital. Lebanese journalist Luna Safwan tweeted, “Migrant worker grabs toddler and saves her from shattered glass and windows as the second big explosion erupted in Beirut earlier today. She did not even think. Migrant workers deserve better in #Lebanon – this woman is a hero.”

Asiya Haouchine

is an Algerian-American writer who graduated from the University of Connecticut in May 2016, earning a BA in journalism and English. She was an editorial intern and contributing writer for Warscapes magazine and the online/blog editor for Long River Review. She is currently studying for her Master’s in Library and Information Science. @AsiyaHaou

Congolese overlook the site of a copper mine in the country’s Haut-Katanga province. Fairphone. CC BY-NC 2.0

Coronavirus—the Newest Excuse for Miners’ Mistreatment in the Congo

In the far south of the Democratic Republic of Congo lies the Copperbelt, a region that leads Africa in copper production and accounts for 70% of the world’s cobalt supply. The area’s mines play a key role in supplying the world with electrical wires and the batteries found inside smartphones and electric cars.

The Congo’s Copperbelt is also a region of severe worker mistreatment. Miners, often children, receive around $1 a day as they toil in shafts prone to collapse for long hours. This occurs while cobalt’s market price hovers at nearly $30,000 per ton.

As COVID-19 ravages Africa, copper and cobalt mines in the Congo have adjusted by instituting harsh rules to curb the virus’s impact on their production levels. The mines’ provisions have, unsurprisingly, not been in workers’ favor. The adjustments, confirmed by workers and union representatives, include:

· Mandatory confinement at mine sites, 24 hours per day, or risk losing employment

· Extended shifts without receiving additional pay

· Inadequate food and water rations

· Overcrowded sleeping arrangements and unsanitary toilet and hand-washing facilities

· Limited or nonexistent communication about the confinement’s duration or future COVID-19 measures

The response to allegations of further worker mistreatment in the Congo has been immediate. Eleven human rights groups, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, sent a letter to 13 mining corporations across the region setting standards for worker treatment.

“We believe that companies around the world will be remembered,” the letter states, “by how they treat their workers during these challenging times. At a minimum, companies should not require workers to be held in mandatory confinement under threat of unemployment, should provide adequate personal protective equipment and access to water and sanitation facilities for all workers, and employ social distancing measures at all times.”

Whether the suggested guidelines will be followed in the Copperbelt remains to be seen. Mining titans Glencore, Eurasian Resources Group, Chemaf, Huayou Cobalt and Ivanhoe Mines declined to immediately respond to requests for comment.

Workers shovel copper into railway cars at a processing plant in Lubumbashi, from where it will be sent abroad. International Labour Organization ILO. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Pressure has been mounting on copper and cobalt producers – and their recipients – for years. International Rights Advocates, a human rights lobbying group, filed suit against Apple, Google, Microsoft, Dell and Tesla in December 2019 accusing them of “knowingly benefiting from” the use of child labor at Congolese mines. While the companies restated their commitment to “only sourcing responsibly-produced materials,” very few tangible steps have been taken.

The problem, then, continues today. Though Apple revealed its full list of cobalt suppliers upon request, many major companies cannot verify that their supply chains are free of worker mistreatment. Faced with slim human rights pressure from buyers and a generally impoverished workforce, most cobalt and copper producers feel little incentive to change. Their COVID-19 response so far stands as only the most recent example.

Accountability remains the first step toward ending the mistreatment of Congolese miners. Supply chain traceability alone could prevent companies from buying minerals unearthed by unprotected workers facing mandatory confinement. A positive step came in late May when Huayou Cobalt, China’s top producer, agreed to temporarily stop sourcing cobalt from the informal sector “until relevant standards can be recognized and supported by the whole industry.”

While this step is welcome, much more can be done. COVID-19’s spread complicates mines’ production efforts, but by no means necessitates mandatory confinement, threats to employment, and steep cuts to health and wellness standards. Groups such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and Rights and Accountability in Government are working to fight against worker mistreatment, and this letter is just the first move.

Stephen Kenney

is a Journalism and Political Science double major at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He enjoys sharing his passion for geography with others by writing compelling stories from across the globe. In his free time, Stephen enjoys reading, long-distance running and rooting for the Tar Heels.

“Uighur Women” by Sean Chiu is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

The Coronavirus Brings Added Concern For Uighur Muslims

More than 200,000 Uigher Muslims from northwest China have been forced into re-education camps (akin to concentration camps), where they experience forced labor, political indoctrination and even torture. These groups are now at high risk for Covid-19 due to overcrowding and poor ventilation in the camps.

Read MorePresident Donald Trump takes questions at Coronavirus update briefing, 3/14/20. Official White House photo by Shealah Craighead. Public Domain.

The Authoritarian Repercussions of Coronavirus

Around the world, Coronavirus has led to an increase in government surveillance, crackdowns on journalism, restrictions on movement and less restrictions on legislature. There is no doubt that they infringe upon civil liberties and may remain in effect long after the spread of the virus has calmed down.

Read MoreAcademic Freedom: Repressive Government Measures Taken Against Universities in More Than 60 Countries

Universities around the world are increasingly under threat from governments restricting their ability to teach and research freely. Higher education institutions are being targeted because they are the home of critical inquiry and the free exchange of ideas. And governments want to control universities out of fear that allowing them to operate freely might ultimately limit governmental power to operate without scrutiny.

My recent report, co-authored with researcher Aron Suba for the International Centre for Not-for-Profit Law, has found evidence of restrictive and repressive government measures against universities and other higher education institutions in more than 60 countries.

This includes government interference in leadership and governance structures to effectively create state-run institutions that are particularly vulnerable to government actions. It also includes the criminalisation of academics for their work as well as the militarisation and securitisation of campuses through the presence of armed forces or surveillance by security services. We also found evidence that students have been prevented from attending university because of their parents’ political beliefs, while others have been expelled or even imprisoned for expressing their own opinions.

Some of the more shocking examples of repressive practices have been widely publicised, such as the firing of thousands of academics and jailing of others in Turkey. But much of what is happening is at an “administrative” level – against individual institutions or the entire higher education system.

There are examples of governments that restrict access to libraries and research materials, censor books and prevent the publication of research on certain topics. Governments have also stopped academics travelling to meet peers, and interfered with curricula and courses. And our research also found governments have even interfered in student admissions, scholarships and grades.

Repression, intimidation

Hungary provides a particularly glaring recent example of government interference with university autonomy. The politicised targeting of the institution I work at –- Central European University –- has been well documented. But the government has also recently acted against academic life in the country more broadly. It has effectively prohibited the teaching of a course (gender studies) and taken control of the well-regarded Hungarian Academy of Social Sciences.

What makes the Hungarian example especially disturbing is that it is happening within the European Union – with seemingly no consequences for the government. This is despite the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights which states that: “The arts and scientific research shall be free of constraint. Academic freedom shall be respected.” Meanwhile the Hungarian government still has all the privileges of being an EU member state, which includes receiving large sums of EU money.

Public demonstration in front of the Hungarian Academy of Science building against the removal of the Academy Science Research Institute’s autonomy. Istvan Balogh/Shutterstock

The inexplicable failure by the EU to enforce its own standards is particularly troubling and helps to normalise this behaviour. Indeed, there are clear signs such repressive practices are spreading. Anti-human rights legislation, policy and practice that begins in one country is frequently copied in another. Anti-civil society legislation recently adopted in Hungary and Israel, for example, which aims to stop protests and minimise the number of organisations receiving funds from abroad, was previously adopted in Russia.

Repressive practices against universities are starting to spread in Europe. Earlier this year it was reported that the Ministry of Justice in Poland planned to sue a group of criminal law academics for their opinion on a new criminal law bill.

Academics in distress

The freedom of academics and university autonomy is not entirely without scrutiny. There are some excellent organisations, such as Scholars At Risk and the European University Association who actively monitor this sector. But, at an international level, university autonomy is rarely raised when governments’ human rights records are being examined. And there is no single organisation devoted to monitoring the range of issues identified in our recent report.

Without proper monitoring, universities, academics and students are even more vulnerable because there is little attention paid to these issues. And there is little pressure on governments not to undertake repressive measures at will.

Thousands demonstrate in central Budapest against higher education legislation seen as targeting the Central European University. Drone Media Studio/Shutterstock

A global monitoring framework is needed, underpinned by a clear definition of university autonomy. The UN and EU institutions also need to pay more attention to the dangers that such attacks on universities pose to democracy and human rights. A stronger line against governments who are acting in violation of existing standards should also be taken.

Universities should be autonomous in their operations and exercise self-governance. These institutions are crucial to the healthy functioning of democratic societies. Yet academic spaces are closing in countries around the world. This should be a concern for all. The time for action is now, before this trend becomes the new norm.

Kirsten Roberts Lyer is a Associate Professor of Practice, Acting Director Shattuck Centre, Central European University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Saudi Women Protesting Driving Ban Remain Jailed, Details of Trial Unclear

In 2017, the driving ban was lifted for Saudi women. However, the women who vocally protested the ban have been jailed, subjected months of torture and unable to communicate with their families.

Lina Al-Hathloul speaking about the imprisonment of her sister, Loujain. POMED. CC BY 2.0

June 24th, 2018 marked the first day women in Saudi Arabia could legally obtain drivers licenses, following an announcement by King Salman in September that women driving would be considered acceptable under sharia law. By March of 2019, more than 70,000 Saudi women had received a license. Under the interpretation of sharia law enforced by the Saudi government, women are effectively minors, subject to guardianship by their fathers, husbands, or even their sons should their husbands pass away or become otherwise unable to fulfill the role of guardian. Women must receive permission to enroll in school, open bank accounts, sign contracts, or acquire a passport, to name a few of the many restrictions women face under guardianship laws.

Regarding the announcement of the end of the driving ban, Eman al-Nafjan writes in her blog, “Initially I was overwhelmed with my own powerlessness as a woman living in a patriarchal absolute monarchy. Were our efforts the reason the ban was lifted? Or was it a decision that had been made regardless of our struggles?” Dr. al-Nafjan is one of eleven women who was detained, subject to torture, solitary confinement, and threats of rape and death—more than once by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman himself—in 2018 as a result of their protests against the ban. The protests against the driving ban began in 1990, and have lead to the arrest, imprisonment, and severe punishment of many individuals. Of the eleven arrested in May-June 2018, some were released on bail. Al-Nafjan, as well as two other women, Loujain al-Hathloul and Nouf Abdulaziz, have borne the brunt of cruelty at the hands of the Saudi government, and as a result have received the most media attention. Their trials began in late March of 2019, however little is known of their current situation.

Nouf Abdulaziz, one of the women held in prison, writes in a letter sent during her detainment: “Hello my name is Nouf, and I am not a provoker, inciter nor a wrecker, nor a terrorist, nor a criminal nor a traitor.” The women imprisoned have sought justice for their fellow women, and we must honor their work by seeking justice on their behalf. There exists a clear duplicity in the West’s reaction to these human rights violations: although outwardly supportive of human rights, the U.S., France, and the U.K. have been complicit in the Saudi regime’s actions by maintaining close economic and security ties with Saudi Arabia. At the end of her letter, Abdulaziz implores her readers: “if what is happening does not please you, help our people to see clearly that our sister in the homeland is mistreated and she does not deserve other than her freedom, to maintain her dignity and to have the warmth in her parents [sic] arms, that has been taken away from her.” Many human rights organizations have spoken up on behalf of these activists, and Abdulzaziz, al-Hathloul, and al-Nafjan were awarded the 2019 PEN Freedom to Write Award for their work.

In this vein, Amnesty International marked May 2018-May 2019 a “year of shame for Saudi Arabia” due especially to its treatment of women’s rights activists and the assassination of Jamal Khashoggi, a dissident Saudi journalist. Although Crown Prince Salman, accepting the position of Crown Prince in 2017, labeled himself a reformer, he immediately launched a campaign to repress dissenters of the regime. In this way, the worries expressed by Nafjan were prescient: the Saudi government lifted the driving ban in an effort to improve international opinion, as well as increase the number of women working in Saudi Arabia’s flagging private sector, not with genuine progressive intent. Those who most vehemently spoke up for the rights of women were made examples of for other dissenters. While ultimately a victory for the greater female Saudi population, the patriarchal regime insisted upon a last word—in the form of human rights violations against the very women who created the momentum for the lifting of the ban.

HALLIE GRIFFITHS is an undergraduate at the University of Virginia studying Foreign Affairs and Spanish. After graduation, she hopes to apply her passion for travel and social action toward a career in intelligence and policy analysis. Outside of the classroom, she can be found, quite literally, outside: backpacking, rock climbing, or skiing with her friends.

Chile Protests Escalate as Widespread Dissatisfaction Shakes Foundations of Country’s Economic Success Story

Chile’s capital city Santiago appears dynamic and bustling, complete with gleaming skyscrapers and a modern metro network. Against the backdrop of the snow-topped Andes mountains, the Costanera Tower – South America’s tallest building – symbolises the country’s open neoliberal economy and mass consumption society.

But protests have rocked the country, challenging this image of stability and prosperity.

Following a government proposal to increase the price of metro tickets, students began to dodge metro fares in protest on October 14, jumping the turnstiles en masse and setting metro stations on fire. The protests soon spread within Santiago and to other Chilean cities, leading President Sebastian Piñera to declare a state of emergency and daily curfews on October 18. This legislation, which dates from the dictatorship era of the 1970s and 80s, allows the military to patrol the streets.

But the move has led to an escalation of the protests, as thousands of Chileans disobeyed the curfews by marching peacefully against government policy and violent repression on a daily basis, calling for Piñera to resign.

The images of soldiers and tanks on the streets, dispersing protesters with water cannon, tear gas, and physical violence, recall the images of military repression during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet between 1973 and 1990. The economic and ideological legacies of the Pinochet era as well as the nature of Chile’s transition to democracy are key to understanding the reasons for the protests. The anger of those on the streets is as much a reflection of the country’s high inequality as it is of these unresolved legacies.

Much of the media coverage of the protests has focused on the spectacle of looting, vandalism, and soldiers beating the protesters. Since the protests started, 18 people have died and there have been 3,000 arrests. But there are wider causes behind these events. The protests emerged in the middle of growing dissatisfaction with high levels of inequality and a high cost of living.

Income inequality has not improved in Chile since the days of the military dictatorship. World Inequality Database

On the surface, Chile looks like an economic and political success story, as the country’s GDP growth has outpaced that of Latin America as a whole in recent years, but many Chileans are struggling. The metro fares have come to symbolise what they feel is the unjust distribution of income and social spending.

Legacy of Pinochet era

Like the state of emergency, Chile’s social and economic policies also date from the dictatorship. Neoliberal reforms were introduced in the mid-1970s by Pinochet and his team of American-trained economists, known as the “Chicago Boys”. The reforms took place in the context of violent repression. Official investigations showed that 3,065 people were murdered by state agents during the dictatorship, 40,000 tortured, and hundreds of thousands forced into exile.

The 1970s reforms included the elimination of subsidies, welfare reform, and the privatisation of state-owned companies, the health sector, education and pensions. Pinochet’s reforms led to high levels of unemployment, declining real wages, and expensive social services, such as education. The impact is clear today in education, characterised by low levels of public spending and highly unequal access to good-quality schools and universities. Between 2011 and 2013 students organised mass demonstrations against Chile’s education policies, and dissatisfaction remains.

Chile turned from a military to a civilian government in 1990, following the 1988 referendum in which Pinochet was defeated. But due to the nature of the transition, social and economic policies changed very little. Pinochet negotiated his departure in such a way that the armed forces kept control of the political process, including his own appointment as a lifelong senator. The 1980 military constitution – which is still in place today – has allowed Piñera to declare the controversial state of emergency to deal with the protests. Although some of the military control structures have been dismantled since Pinochet’s death in 2006, the civilian governments on the right and the left have had a limited appetite to address the country’s inequalities.

Anger on the streets of Santiago. Fernando Bizerra Jr/EPA

In response to the protests, on October 22 Piñera suspended the planned fare increases and announced a spending package of reforms to address the protestors’ concerns. The fact that Chileans continue to protest around the country shows that many people feel these measures are too little, too late.

Given the long historical roots of the inequalities, it’s unlikely that one-off extra spending can address the country’s structural problems. Even if the government’s intention has been to de-escalate the situation, its hardline response to the protests signals growing polarisation rather than a quick resolution to the issues.

Marieke Riethof is a Senior Lecturer in Latin American Politics, University of Liverpool

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Escalations in Violence in Hong Kong Could Prove Perilous to Human Rights

“A protestor wearing a Guy Fawkes mask in October 2019.” Honcques Laus. CC0.

Demonstrators have seemed to reach a stalemate against the government of Hong Kong, which refuses to accede to the demands of the protesters. Given the rapid escalations in violence and the willingness of the police to employ excessive force, a stalemate could have serious consequences for the state of human rights in Hong Kong.

Protests in Hong Kong began in late April 2019, in reaction to the raising of an extradition bill, which would have permitted the extradition of citizens of Hong Kong to mainland China. Pro-democracy protesters see the extradition bill as a significant acquiescence of Hong Konger’s sovereignty to mainland China, as Hong Kong remains a territory not technically under the direct purview of the Chinese government. The specific worry is that Beijing would use the extradition bill to suppress the growing pro-democracy sentiment among younger generations of Hong-Kongers by demanding that Hong Kong hand over its activists and successful con-China politicians. They represent a movement that has been developing since the late 1990s, focused on maintaining Hong Kong’s distance in relation to the Central People’s Republic in Beijing, with the eventual aim of bringing fully-democratic elections to Hong Kong.

Presently, the citizens of Hong Kong are allowed free speech and rights to free assembly and association, as outlined in the Basic Law. The government and election structure of Hong Kong is quasi-representative. There are 1,200 electors who ostensibly select officials: representatives of various economic sectors, business interests, and the affluent of Hong Kong. However, the central mainland government exercises a great deal of control over the political proceedings of Hong Kong; the incumbent Chief Executive Carrie Lam was openly favored by China’s President, Xi Jinping. While the extradition bill was removed from the table following the outbreak of protests, the potential for democracy in Hong Kong seems to hang in the balance, as demonstrated in Executive Lam’s unwillingness to accede to the demands of the protesters, and in Beijing’s continued support for Lam.

The protestors have issued a list of demands beyond the reneging of the proposed extradition bill, repealed in September, that includes investigation into police actions as well as amnesty for protesters in custody, complete universal suffrage, and Lam’s withdrawal from her post as Chief Executive of Hong Kong. The government of Hong Kong has issued a hardline stance, supported explicitly by Xi Jinping and the Central People’s Republic. In her refusal to acquiesce to demands, Lam pushes the protests in Hong Kong towards a path of greater uncertainty; given the perseverance demonstrated by the protesters, it seems that the situation will only continue to escalate.

Consequently, the first weeks of November have seen significant escalations in the protests in Hong Kong: on November 7th, a university student died after he fell from the top of a parking deck during a skirmish with the police. Monday November 11th saw major instances of violence, in which a police officer shot a protester at close range, and a pro-China counter-protester was set on fire by a group of demonstrators. Protesters and police alike have exhibited violent tactics since the inception of the protests. Police have not shied away from tear gas and rubber bullets, as well as employing excessive physical force towards protesters and members of the press. Demonstrators have also used tactics such as vandalism and violence against those believed to be pro-China.

However, equating police violence with the actions of the protesters carries dangerous human rights implications; the police act from a privileged position because of the backing they receive from both the government of Hong Kong as well as that of mainland China. The protesters have only the solidarity they experience among one another. Violence by protesters is the impetus of an individual working in conjunction with other individuals; excessive force against protesters by the police is a hit by the state in its entirety.

In this way, escalating patterns of police violence prove pernicious, because they undermine the human rights of Hong Kongers, and breed complications for a hypothetical future peace process. Instances of excessive violence towards the press prove especially destabilizing, because the suppression of information perpetuates the murkiness that allows the police to continue to carry out extreme, and in many cases illegal acts of retribution against demonstrators. As it stands, the violence in Hong Kong will only continue its escalation should the government of Hong Kong maintain its staunch refusal of concessions. A stalemate could have alarming consequences for the state of human rights in Hong Kong, as the police have already turned to violent tactics involving excessive uses of force, and the demonstrators have, in turn, only increased their fervor in furthering their demands.

HALLIE GRIFFITHS is an undergraduate at the University of Virginia studying Foreign Affairs and Spanish. After graduation, she hopes to apply her passion for travel and social action toward a career in intelligence and policy analysis. Outside of the classroom, she can be found, quite literally, outside: backpacking, rock climbing, or skiing with her friends.

Newborn babies in a Bangkok hospital on Dec. 28, 2017.They are wearing dog costumes to observe the New Year of the dog. Athit Perawongmetha/Reuters

What the US Could Learn from Thailand about Health Care Coverage

The open enrollment period for the Affordable Care Act (ACA) draws to a close on Dec. 15. Yet, recent assaults on the ACA by the Trump administration stand in marked contrast to efforts to expand access to health care and medicine in the rest of the world. In fact, on Dec. 12, the world observed Universal Coverage Day, a day celebrated by the United Nations to commemorate passage of a momentous, unanimous U.N. General Assembly resolution in support of universal health coverage in 2012.

While the U.N. measure was nonbinding and did not commit U.N. member states to adopt universal health care, many global health experts viewed it as an achievement of extraordinary symbolic importance, as it drew attention to the importance of providing access to quality health care services, medicines and financial protection for all.

Co-sponsored by 90 member states, the declaration shined a light on the profound effect that expansion of health care coverage has had on the lives of ordinary people in parts of the world with far fewer resources than the U.S., including Thailand, Mexico and Ghana. Can the U.S. learn anything from these countries’ efforts?

US and Thailand: A study in contrasts

I came to understand these changes as I researched and wrote my book, “Achieving Access: Professional Movements and the Politics of Health Universalism.” The book offers a comparative and historical take on the politics of universal health care and AIDS treatment, featuring Thailand as the primary case. For me, Thailand’s remarkable achievements also put into perspective some of the work we still have to do here in the United States with respect to health reform.

Before the reform, Thailand had four different state health insurance schemes, which collectively covered about 70 percent of the population. The reform in 2002 consolidated two of those programs and extended coverage to everyone who did not already receive coverage through the country’s health insurance programs for civil servants and formal sector workers.

Thailand’s universal coverage policy contributed to rising life expectancy, decreased mortality among infants and children, and a leveling of the historical health disparities between rich and poor regions of the country. The number of people being impoverished by health care payments also declined dramatically, particularly among the poor.

However, Thailand’s reform had other important consequences that aimed to make the reform sustainable as well. Sensible financing and gatekeeping arrangements – that tied patients to a medical home near where they lived and provided fixed annual payments for physicians to cover outpatient care – were instituted to curb the kind of cost escalation that has historically been a hallmark of the United States (though it has slowed lately). The reform also improved the quality of care for patients in remote areas by mandating that qualified providers in community hospitals collaborate more extensively with rural health centers.

A computer screen promoting this year’s open enrollment, which will run 45 days. In years past, open enrollment continued for months. Ricky Kresslein/Shutterstock.com

The United States, by contrast, seems to be moving in the opposite direction, both in terms of insurance coverage and health outcomes. Although recent Republican efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act were narrowly defeated, lawsuits that aim to terminate popular pre-existing conditions protections continue. In addition, the Trump administration has sought to weaken the reform in other ways: including by cutting the open enrollment periods, which ends Dec. 15 and lasts 45 days; cutting outreach and advertising for open enrollment; and threatening to suspend risk adjustment payments to private insurers, which help to stabilize the market.

Moreover, effective repeal of the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate through a provision in the 2017 Tax Reconciliation Act that reduces the penalty for not having insurance to zero in 2019 will have the effect of reducing the number of insured. This will have an effect on health insurance markets, likely reducing the number of younger and healthier people that help give balance to health insurance risk pools and that help keep overall costs down. And without the financial protection afforded by health insurance, those who are uninsured may face rising rates of medical bankruptcy, to say nothing for the loss of access to sorely needed medical care.

Learning from Thailand

To be sure, the Thai and American contexts are very, very different. While health spending stands at around 4 percent of GDP in Thailand, in America nearly 20 percent, or one-fifth, of the country’s total economic output is spent on health. Yet, in some ways, that makes Thailand’s achievement all the more remarkable. And while no program is perfect, Thailand’s reform is one of the reasons that health costs in Thailand have remained so low, despite such a dramatic increase in coverage.

The use of generic drugs in Thailand is a strategy to keep costs low. Room's Studio/Shutterstock.com

Reformers also drew on other innovative policy instruments to keep costs down, including the Government Pharmaceutical Organization that produces generic medication for the universal coverage program and the use of compulsory licenses, which allow governments to produce or import generic versions of patented medication under WTO law.

The Affordable Care Act similarly sought to improve access, while curbing costs. Some of the most important mechanisms to curb costs fell victim to the legislative process however. Most notably, lobbyists succeeded in killing the “public option,” a government (as opposed to private) health insurer with much lower administrative costs that aimed to bring costs down among private health insurers through competition with them.

Although the reform in Thailand was popular among the masses, it also saw its share of detractors. Medical associations that represented doctors who saw the policy as a threat came out against it. Likewise, beneficiaries of the existing programs for civil servants and employees of large, tax-paying businesses feared that their own benefits would be diluted by a new single payer program. Despite progress expanding access to everyone, the new program introduced in 2002 still sits alongside separate programs for civil servants and employees of large, tax-paying businesses.

What the contrast makes clear, however, is that reforms done properly can expand access while at the same time instituting measures that help to contain costs. The U.S., in my view, should pursue similarly creative and constructive reforms that seek to do both.

What does that look like in the United States? To me, that means preserving the ACA’s individual mandate and protections related to pre-existing conditions; creating (or expanding) a public insurer like Medicare to compete alongside private insurers and keep costs down; addressing the lack of price transparency in our nation’s hospitals; and actively negotiating with pharmaceutical companies and hospitals to bring costs of drugs and health care down for millions.

Done sensibly, developing nations like Thailand are proving that they do not have to join the ranks of the world’s wealthiest nations for their citizens to enjoy access to health care and medicine. Using evidence-based decision-making, even expensive benefits, like dialysis, heart surgery and chemotherapy, need not remain out of reach. Policymakers in all countries can institute reforms using tools that promote cost savings at the same time they improve access and equity.

While efforts to implement universal coverage are not without challenges, these results suggest that leaders in Congress would do well to learn from countries like Thailand as they chart a fiscally responsible path forward on health care.

JOSEPH HARRIS is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Boston University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Community post office, Freetown Christiania. Helen Jarvis. , Author provided

Degrowth and Christiania – I saw How Copenhagen’s Collective Living Experiment Can Work

Since the first squatters arrived in 1971, the self-proclaimed Freetown of Christiania has inspired radical thinking and social experimentation. Affectionately described as “loser’s paradise”, the squat became a haven for young people unable to access affordable housing in Copenhagen, and activist pioneers from all over the world.

In July 2012, Christiania struck a deal with the Danish state to “normalise” its status. The change was fraught: after 40 years of illegal occupation, a community of activists fiercely opposed to the idea of private property had to establish a foundation and purchase the entire site, with the exception of some features, which were heritage listed.

The deal enabled Christiania to buy itself free of speculation, as a common resource for everybody and nobody. Today, Christiania receives hundreds of thousands of visitors each year, making it the most popular tourist destination in Copenhagen after Tivoli Gardens and the statue of The Little Mermaid.

Growth and the good life

It’s considered normal for cities and states to measure success in terms of economic growth. But critics point to the treadmill of addictive consumption, property speculation, long working hours, debt, waste, one-upmanship, fast food and short-lifespan technologies that unending growth sets in motion. Opposing this trend, communities such as Christiania pursue “degrowth” by prioritising human relations over market relations; maximising sharing, togetherness, social justice and the health of the planet.

The pressures to conform with mainstream society can be divisive for the 800 or so residents managing their lives communally in Christiania. Big decisions are made through a decentralised democratic structure: 14 area meetings and a “common meeting” must reach consensus between artists, activists and cannabis dealers on Pusher Street.

A self-built home. seier+seier/Flickr., CC BY

In 2012, a minority of residents wanted to be allowed to buy and sell homes that they had built or renovated for themselves. The final deal with the Danish state prevented this. Residents have the right to occupy, but not to buy or sell their homes or businesses. The whimsical variety of domestic architecture that has evolved makes Christiania visibly distinct from surrounding up-market neighbourhoods.

The residents’ resistance

I know from my brief time living in Christiania as researcher in residence in 2010 that degrowth values were practised there long before this term became associated with a broad movement of alternative, ethical and ecological actions.

From the outset, it was the Christiania way to renovate and adapt rather than to tear down existing buildings, and to build with reclaimed materials at minimum costs. This also made it possible to get by on a low income, with reduced hours in paid employment, giving residents a way to resist the earn-to-spend treadmill.

Christiania is known as a place where nothing goes to waste. Numerous craft skills and social enterprises thrive on a culture of making do and mending. Elsewhere in Copenhagen similar local livelihoods fail to flourish under profit maximising conditions. The community has won prizes for comprehensive garbage collection and recycling. The collectively run Green Hall trades in salvaged and repurposed building materials.

Stage made from compressed cardboard for ‘Dancing at the Trasher’, 2010. Helen Jarvis.

Six years on

This summer, Christiania hosts a festival of degrowth, to show that it is ethical and green to resist the burden of conspicuous consumption. The festival coincides with an exhibition of archives on the history of the place, which forms part of the sixth International Degrowth Conference taking place just across the Öresund Bridge in Malmö, Sweden.

Social investment with the Christiania people’s share. Helen Jarvis.

One example of grassroots degrowth since 2012 is the 12.8m Danish Kroner (£1.5m) raised from a social model of investment: the “People’s Christiania Share”. The scale of this crowdfunding (shares are symbolic and have no financial value) outstrips previous experiments with alternative currency. These include payment of a Christiania wage for community jobs – for example, working in the bakery, gardens, laundry, waste collection or machine hall – which functions much like the degrowth policy of basic income, where everyone is paid a minimum stipend.

By comparison, police estimate the cannabis market on Pusher Street to be worth 635m Danish Kroner (£74m) annually. While social models of investment benefit Christiania, profits from the hash market drive growth and speculation elsewhere. Recognising this conflict, residents chose in May this year to shut down Pusher Street temporarily. Younger residents are driving this shift from individual freedom (to profit from criminal activity) to mutual responsibility (for future generations and the planet). This coincides with broad based support for the recent crackdown on intimidating cannabis markets in Christiania.

The festival of degrowth will introduce visitors to a “village of alternatives”. My research shows that Christiania is an inspirational space to think differently about conventional standards of living, precisely because of the absence of private property. A collective shift in mindset can be achieved here, which would not be possible in neighbourhoods of conventional single family homes.

Making the magic

Yet puzzles remain, when it comes to practising sustainable degrowth at scale. One reason why Christiania’s car-free landscape is so “magical” is that residents live at remarkably low density: at first glance, they seem to live in a public park.

Low-density living. Shutterstock.

While this site might otherwise be expected to accommodate several thousand people in high density social housing, the legal safeguards of the 2012 deal endow Christiania exceptional experimental status. This allows residents to take risks with living creatively on a low income, enjoying close friendships in place of material consumption.

There are lessons here for places where degrowth is dismissed as impossibly Utopian, limited to fringe green debates and reduced goals of “sufficient living standards”. In the UK, state sponsored private property and ownership impose smaller private homes, rather than collective ownership of private and shared spaces.

But from Christiania, we learn that smaller private spaces only benefit sustainable degrowth when combined with collective ownership and generous community space for shared use: people come together to share skills and collectively manage scarce resources to reduce consumption. The hope is that as young green activists gather in Christiania this summer, thousands of visitors will look favourably upon collective living as the new normal.

HELEN JARVIS is a Reader in Social Geography at Newcastle University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

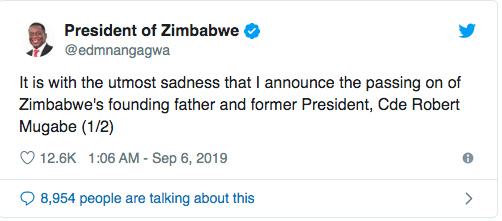

Robert Mugabe during his swearing-in ceremony in Harare, 2008. The former Zimbabwean president has died aged 95. EPA-EFE

Robert Mugabe: As Divisive in Death as he was in Life

Robert Mugabe, the former president of Zimbabwe, has died. Mugabe was 95, and had been struggling with ill health for some time. The country’s current President Emmerson Mnangagwa announced Mugabe’s death on Twitter on September 6:

The responses to Mnangagwa’s announcement were immediate and widely varied. Some hailed Mugabe as a liberation hero. Others dismissed him as a “monster”. This suggests that Mugabe will be as divisive a figure in death as he was in life.

The official mantra of the Zimbabwe government and its Zimbabwe African National Patriotic Front (Zanu-PF) will emphasise his leadership of the struggle to overthrow Ian Smith’s racist settler regime in what was then Rhodesia. It will also extol his subsequent championing of the seizure of white-owned farms and the return of land into African hands.

In contrast, critics will highlight how – after initially preaching racial reconciliation after the liberation war in December 1979 – Mugabe threw away the promise of the early independence years. He did this in several ways, among them a brutal clampdown on political opposition in Matabeleland in the 1980s, and Zanu-PF’s systematic rigging of elections to keep he and his cronies in power.

They’ll also mention the massive corruption over which he presided, and the economy’s disastrous downward plunge during his presidency.

Inevitably, the focus will primarily be on his domestic record. Yet many of those who will sing his praises as a hero of African nationalism will be from elsewhere on the continent. So where should we place Mugabe among the pantheon of African nationalists who led their countries to independence?

Slide into despotism

Most African countries have been independent of colonial rule for half a century or more.

The early African nationalist leaders were often regarded as gods at independence. Yet they very quickly came to be perceived as having feet of very heavy clay.

Nationalist leaders symbolised African freedom and liberation. But few were to prove genuinely tolerant of democracy and diversity. One party rule, nominally in the name of “the people”, became widespread. In some cases, it was linked to interesting experiments in one-party democracy, as seen in Tanzania under Julius Nyerere and Zambia under Kenneth Kaunda.