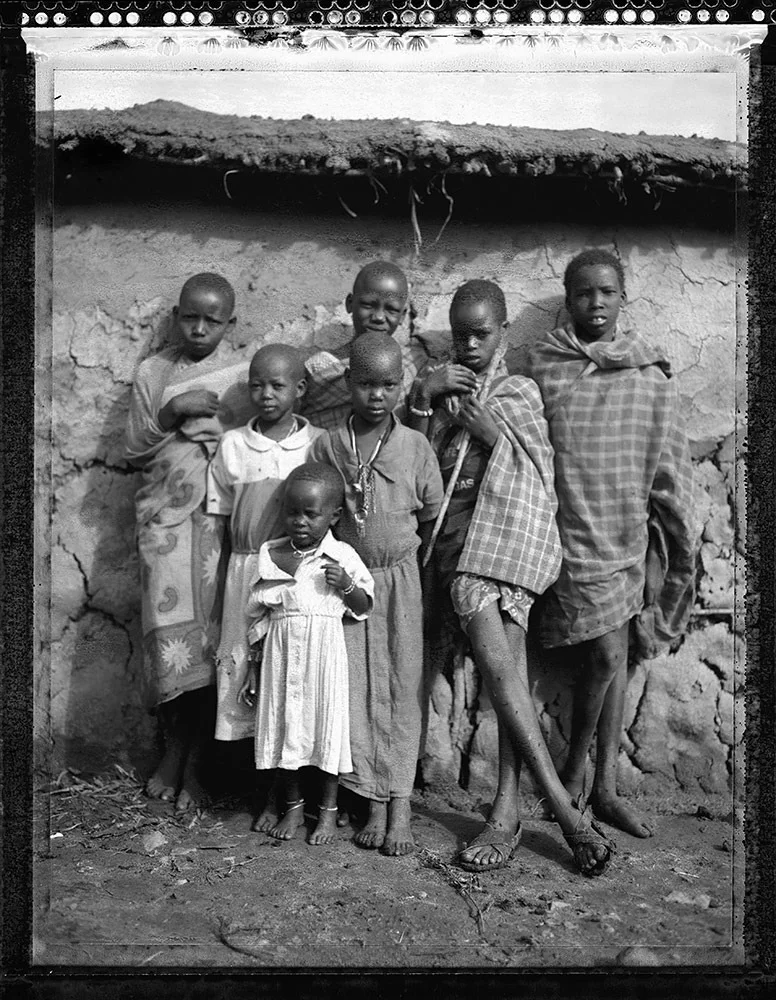

In mid-March, shortly after Kenya’s first confirmed COVID-19 case, the word “corona” began circulating around western Kenya’s villages. Young people used the word as a novelty, and the overall population remained preoccupied with existing illnesses. “This is a disease for whites,” said Sylvanus, a local father of seven. When calling after white people on the street, children replaced their traditional “mzungu!” (white person) with “coronavirus!” At this point, Europe was the pandemic’s epicenter. Kenyans felt that this foreign virus was removed from their world.

However, Kenya’s high prevalence of preexisting health conditions renders a significant portion of the population immunocompromised and therefore vulnerable to the coronavirus. In a country experiencing health issues such as HIV, tuberculosis, diabetes and malaria, the pandemic has posed a threat to an already fragmented health care system. Although less than 4% of Africa’s population is over the age of 65, countries such as Kenya have seen high coronavirus mortality rates.

Global evidence shows that people with underlying medical conditions are at a greater risk from COVID-19. In 2019, half a million Kenyans were living with diabetes, and over half of accounted deaths were associated with noncommunicable diseases. Currently, Kenya’s health care system is structured to manage individual diseases, rather than multiple ones. Because patients frequently carry more than one health condition, the health care system has been overstretched and inadequate. HIV, tuberculosis and malaria treatments are easily accessible, but noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes and cancer often go undiagnosed, and care is costly. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these shortcomings, as social distancing restrictions prevent Kenyans from accessing medical resources, and a surge of coronavirus cases imposes a double burden of disease. Additionally, front-line workers with undiagnosed, chronic illnesses have critically compromised their health, and hospitals have dealt with equipment shortages.

Transcontinental travel has heavily contributed to the increase in COVID-19 cases across Africa. In order to minimize Kenya’s number of infections, President Uhuru Kenyatta stopped all flights from Europe. Kenyatta also imposed a national curfew and restricted movement between populated areas. Domestically, middle-class, urban dwellers have carried the virus into rural areas. On Kenyan television, villagers have urged educated, urban residents to remain in the city, instead of threatening the lives of others.

In African countries, lockdowns are nearly impossible to implement because they would spur social and economic crises. Many people rely on cash earned daily to sustain themselves and their families. A strict lockdown would result in poverty and starvation. Kinship systems also play a crucial role in social welfare, as relatives care for one another. For people already barely getting by, cutting these social ties would be dangerous. Finally, a lockdown would interrupt the supply chains of essential drugs, preventing access to tuberculosis, HIV and malaria treatments.

According to several African presidents, developed countries are failing to fulfill their pledges of financial support and debt relief. Throughout the pandemic, outside aid has not met the continent’s needs. While wealthy countries in the global north have funneled trillions of dollars into their own stimulus packages and health initiatives, the global south cannot afford such measures. With limited testing capacity, Africa has not confirmed many of the world’s COVID-19 cases, but the continent has been grossly affected by the economic crisis and global trade disruptions. Furthermore, the global shortage of testing kits, hygienic material and personal protective equipment has left developed countries vying for their own supplies, without consideration for underdeveloped nations.