The Mexican border town of Tijuana is home to thousands of Haitians. Most are asylum-seekers, stuck in administrative limbo as they await potential entry to the United States. To help them feel more at-home, Fausta Rosalía—owner of a popular lunch spot—decided to switch up her traditional offerings of tacos and quesadillas to better serve the city’s new residents. Now, she’s cooking Haitian food in the hopes that a taste of home will make life a little bit easier for so many.

Health Needs in Migrant and Refugee Communities

Lack of access to health care, trauma, and poor living conditions all contribute to public health concerns of migrant populations.

The Patrons of Veracruz provide food for migrants traveling across Mexico. Giacomo Bruno. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Over the years of the Trump Administration, stories of maltreatment of migrants either at the border, or well-established in country, keep surfacing. This pattern is mirrored in other countries around the world, often with a large anti-immigration rhetoric. In the US, this has stemmed from a dislike and distrust of illegal immigrants but often spreads to legal migrants and refugees as well, at a huge health cost to those trying to enter.

Trump’s policies to reduce numbers crossing the Mexican border include a, now revoked, policy to separate children from their families and a Remain in Mexico policy that prevents migrants from entering the US while waiting for asylum cases. With this policy over 50,000 migrants have been sent to wait in Mexico. They now live in overcrowded camps with limited access to health care. NGOs struggle to keep up with increasing numbers and problems such as clean water and waste management. US policies are supposed to allow children and those ill or pregnant to remain in the States, but this policy is often ignored.

Once in the US, it is still difficult to access care. Detention centers are overcrowded and trauma from being separated from family can lead to many mental health issues. Migrants are not covered by government programs and have to seek health care through out-of-pocket costs or community health and non-profit organizations. Language and fear limit many from getting care when something might be wrong. Poor migrant working conditions and food insecurity have lasting impacts on migrant health once in the country.

Australia has had similar policies to deter migrants by sending them to wait for asylum on nearby pacific islands where resources are lacking. In 2018, there were almost 1500 detained in Nauru and Papua New Guinea. Health organizations working on the islands found a massive mental health crisis with one third of the 208 people treated on Nauru having attempted suicide. It was found that in the 2017-2018 financial year, the Australian government spent over $320,000 fighting medical transfer requests.

The US and Australia have showcased how inhumane policies surrounding immigration comes at a great health cost. But the majority of refugees and migrants, aren’t in the US and Australia, they are in countries neighboring conflict. In fact, 86% of migrants are in developing countries. Jordan has been extremely generous with accepting refugees from neighboring countries but a large influx during the Syrian Civil War is straining Jordan’s ability to provide. In 2018, they had to increase the cost of medical treatment for refugees, which before 2014 was free, now leaving most refugees unable to cover basic health costs.

The World Health Organization is working to try to make sure migrant health needs are met but with 258 million international migrants, 68 million of which are refugees, it is not an easy job.

DEVIN O’DONNELL’s interest in travel was cemented by a multi-month trip to East Africa when she was 19. Since then, she has continued to have immersive experiences on multiple continents. Devin has written for a start-up news site and graduated from the University of Michigan with a degree in Neuroscience.

Newborn babies in a Bangkok hospital on Dec. 28, 2017.They are wearing dog costumes to observe the New Year of the dog. Athit Perawongmetha/Reuters

What the US Could Learn from Thailand about Health Care Coverage

The open enrollment period for the Affordable Care Act (ACA) draws to a close on Dec. 15. Yet, recent assaults on the ACA by the Trump administration stand in marked contrast to efforts to expand access to health care and medicine in the rest of the world. In fact, on Dec. 12, the world observed Universal Coverage Day, a day celebrated by the United Nations to commemorate passage of a momentous, unanimous U.N. General Assembly resolution in support of universal health coverage in 2012.

While the U.N. measure was nonbinding and did not commit U.N. member states to adopt universal health care, many global health experts viewed it as an achievement of extraordinary symbolic importance, as it drew attention to the importance of providing access to quality health care services, medicines and financial protection for all.

Co-sponsored by 90 member states, the declaration shined a light on the profound effect that expansion of health care coverage has had on the lives of ordinary people in parts of the world with far fewer resources than the U.S., including Thailand, Mexico and Ghana. Can the U.S. learn anything from these countries’ efforts?

US and Thailand: A study in contrasts

I came to understand these changes as I researched and wrote my book, “Achieving Access: Professional Movements and the Politics of Health Universalism.” The book offers a comparative and historical take on the politics of universal health care and AIDS treatment, featuring Thailand as the primary case. For me, Thailand’s remarkable achievements also put into perspective some of the work we still have to do here in the United States with respect to health reform.

Before the reform, Thailand had four different state health insurance schemes, which collectively covered about 70 percent of the population. The reform in 2002 consolidated two of those programs and extended coverage to everyone who did not already receive coverage through the country’s health insurance programs for civil servants and formal sector workers.

Thailand’s universal coverage policy contributed to rising life expectancy, decreased mortality among infants and children, and a leveling of the historical health disparities between rich and poor regions of the country. The number of people being impoverished by health care payments also declined dramatically, particularly among the poor.

However, Thailand’s reform had other important consequences that aimed to make the reform sustainable as well. Sensible financing and gatekeeping arrangements – that tied patients to a medical home near where they lived and provided fixed annual payments for physicians to cover outpatient care – were instituted to curb the kind of cost escalation that has historically been a hallmark of the United States (though it has slowed lately). The reform also improved the quality of care for patients in remote areas by mandating that qualified providers in community hospitals collaborate more extensively with rural health centers.

A computer screen promoting this year’s open enrollment, which will run 45 days. In years past, open enrollment continued for months. Ricky Kresslein/Shutterstock.com

The United States, by contrast, seems to be moving in the opposite direction, both in terms of insurance coverage and health outcomes. Although recent Republican efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act were narrowly defeated, lawsuits that aim to terminate popular pre-existing conditions protections continue. In addition, the Trump administration has sought to weaken the reform in other ways: including by cutting the open enrollment periods, which ends Dec. 15 and lasts 45 days; cutting outreach and advertising for open enrollment; and threatening to suspend risk adjustment payments to private insurers, which help to stabilize the market.

Moreover, effective repeal of the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate through a provision in the 2017 Tax Reconciliation Act that reduces the penalty for not having insurance to zero in 2019 will have the effect of reducing the number of insured. This will have an effect on health insurance markets, likely reducing the number of younger and healthier people that help give balance to health insurance risk pools and that help keep overall costs down. And without the financial protection afforded by health insurance, those who are uninsured may face rising rates of medical bankruptcy, to say nothing for the loss of access to sorely needed medical care.

Learning from Thailand

To be sure, the Thai and American contexts are very, very different. While health spending stands at around 4 percent of GDP in Thailand, in America nearly 20 percent, or one-fifth, of the country’s total economic output is spent on health. Yet, in some ways, that makes Thailand’s achievement all the more remarkable. And while no program is perfect, Thailand’s reform is one of the reasons that health costs in Thailand have remained so low, despite such a dramatic increase in coverage.

The use of generic drugs in Thailand is a strategy to keep costs low. Room's Studio/Shutterstock.com

Reformers also drew on other innovative policy instruments to keep costs down, including the Government Pharmaceutical Organization that produces generic medication for the universal coverage program and the use of compulsory licenses, which allow governments to produce or import generic versions of patented medication under WTO law.

The Affordable Care Act similarly sought to improve access, while curbing costs. Some of the most important mechanisms to curb costs fell victim to the legislative process however. Most notably, lobbyists succeeded in killing the “public option,” a government (as opposed to private) health insurer with much lower administrative costs that aimed to bring costs down among private health insurers through competition with them.

Although the reform in Thailand was popular among the masses, it also saw its share of detractors. Medical associations that represented doctors who saw the policy as a threat came out against it. Likewise, beneficiaries of the existing programs for civil servants and employees of large, tax-paying businesses feared that their own benefits would be diluted by a new single payer program. Despite progress expanding access to everyone, the new program introduced in 2002 still sits alongside separate programs for civil servants and employees of large, tax-paying businesses.

What the contrast makes clear, however, is that reforms done properly can expand access while at the same time instituting measures that help to contain costs. The U.S., in my view, should pursue similarly creative and constructive reforms that seek to do both.

What does that look like in the United States? To me, that means preserving the ACA’s individual mandate and protections related to pre-existing conditions; creating (or expanding) a public insurer like Medicare to compete alongside private insurers and keep costs down; addressing the lack of price transparency in our nation’s hospitals; and actively negotiating with pharmaceutical companies and hospitals to bring costs of drugs and health care down for millions.

Done sensibly, developing nations like Thailand are proving that they do not have to join the ranks of the world’s wealthiest nations for their citizens to enjoy access to health care and medicine. Using evidence-based decision-making, even expensive benefits, like dialysis, heart surgery and chemotherapy, need not remain out of reach. Policymakers in all countries can institute reforms using tools that promote cost savings at the same time they improve access and equity.

While efforts to implement universal coverage are not without challenges, these results suggest that leaders in Congress would do well to learn from countries like Thailand as they chart a fiscally responsible path forward on health care.

JOSEPH HARRIS is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Boston University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

People participate in a candlelight vigil near the White House to protest violence against Sikhs in 2012. AP Photo/Susan Walsh

Why Sikhs Wear a Turban and What it Means to Practice the Faith in the United States

An elderly Sikh gentleman in Northern California, 64-year-old Parmjit Singh, was recently stabbed to death while taking a walk in the evening. Authorities are still investigating the killer’s motive, but community members have asked the FBI to investigate the killing.

For many among the estimated 500,000 Sikhs in the U.S., it wouldn’t be the first time. According to the Sikh Coalition, the largest Sikh civil rights organization in North America, this is the seventh such attack on an elderly Sikh with a turban in the past eight years.

As a scholar of the tradition and a practicing Sikh myself, I have studied the harsh realities of what it means to be a Sikh in America today. I have also experienced racial slurs from a young age.

I have found there is little understanding of who exactly the Sikhs are and what they believe. So here’s a primer.

Founder of Sikhism

The founder of the Sikh tradition, Guru Nanak, was born in 1469 in the Punjab region of South Asia, which is currently split between Pakistan and the northwestern area of India. A majority of the global Sikh population still resides in Punjab on the Indian side of the border.

From a young age, Guru Nanak was disillusioned by the social inequities and religious hypocrisies he observed around him. He believed that a single divine force created the entire world and resided within it. In his belief, God was not separate from the world and watching from a distance, but fully present in every aspect of creation.

He therefore asserted that all people are equally divine and deserve to be treated as such.

To promote this vision of divine oneness and social equality, Guru Nanak created institutions and religious practices. He established community centers and places of worship, wrote his own scriptural compositions and institutionalized a system of leadership (gurus) that would carry forward his vision.

The Sikh view thus rejects all social distinctions that produce inequities, including gender, race, religion and caste, the predominant structure for social hierarchy in South Asia.

A community kitchen run by the Sikhs to provide free meals irrespective of caste, faith or religion, in the Golden Temple, in Punjab, India. shankar s., CC BY

Serving the world is a natural expression of the Sikh prayer and worship. Sikhs call this prayerful service “seva,” and it is a core part of their practice.

The Sikh identity

In the Sikh tradition, a truly religious person is one who cultivates the spiritual self while also serving the communities around them – or a saint-soldier. The saint-soldier ideal applies to women and men alike.

In this spirit, Sikh women and men maintain five articles of faith, popularly known as the five Ks. These are: kes (long, uncut hair), kara (steel bracelet), kanga (wooden comb), kirpan (small sword) and kachera (soldier-shorts).

Although little historical evidence exists to explain why these particular articles were chosen, the five Ks continue to provide the community with a collective identity, binding together individuals on the basis of a shared belief and practice. As I understand, Sikhs cherish these articles of faith as gifts from their gurus.

Turbans are an important part of the Sikh identity. Both women and men may wear turbans. Like the articles of faith, Sikhs regard their turbans as gifts given by their beloved gurus, and their meaning is deeply personal. In South Asian culture, wearing a turban typically indicated one’s social status – kings and rulers once wore turbans. The Sikh gurus adopted the turban, in part, to remind Sikhs that all humans are sovereign, royal and ultimately equal.

Sikhs in America

Today, there are approximately 30 million Sikhs worldwide, making Sikhism the world’s fifth-largest major religion.

‘A Sikh-American Journey’ parade in Pasadena, Calif. AP Photo/Michael Owen Baker

After British colonizers in India seized power of Punjab in 1849, where a majority of the Sikh community was based, Sikhs began migrating to various regions controlled by the British Empire, including Southeast Asia, East Africa and the United Kingdom itself. Based on what was available to them, Sikhs played various roles in these communities, including military service, agricultural work and railway construction.

The first Sikh community entered the United States via the West Coast during the 1890s. They began experiencing discrimination immediately upon their arrival. For instance, the first race riot targeting Sikhs took place in Bellingham, Washington, in 1907. Angry mobs of white men rounded up Sikh laborers, beat them up and forced them to leave town.

The discrimination continued over the years. For instance, when my father moved from Punjab to the United States in the 1970s, racial slurs like “Ayatollah” and “raghead” were hurled at him. It was a time when 52 American diplomats and citizens were taken captive in Iran and tension between the two countries was high. These slurs reflected the racist backlash against those who fitted the stereotypes of Iranians. Our family faced a similar racist backlash when the U.S. engaged in the Gulf War during the early 1990s.

Increase in hate crimes

The racist attacks spiked again after 9/11, particularly because many Americans did not know about the Sikh religion and may have conflated the unique Sikh appearance with popular stereotypes of what terrorists look like. News reports show that in comparison to the past decade, the rates of violence against Sikhs have surged.

Elsewhere too, Sikhs have been victims of hate crimes. An Ontario member of Parliament, Gurrattan Singh, was recently heckled with Islamophobic comments by a man who perceived Singh as a Muslim.

As a practicing Sikh, I can affirm that the Sikh commitment to the tenets of their faith, including love, service and justice, keeps them resilient in the face of hate. For these reasons, for many Sikh Americans, like myself, it is rewarding to maintain the unique Sikh identity.

SIMRAN JEET SINGH is a Henry R. Luce Post-Doctoral Fellow in Religion in International Affairs Post-Doctoral Fellow at New York University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

‘Early Days.’ Detail of Frank Happersberger’s pioneer monument, San Francisco, California, 1894. Photo by Lisa Allen. Cynthia Prescott, CC BY-SA

Think Confederate Monuments are Racist? Consider Pioneer Monuments

In San Francisco, there is an an 800-ton monument that retells California history, from the Spanish missions to American settlement. Several bronze sculptures and relief plaques depict American Indians, white miners, missionaries and settlers. A female figure symbolizing white culture stands atop a massive stone pillar.

The design of the “pioneer monument” was celebrated in newspapers across the country when it was erected in 1894. Today, however, activists have argued that the monument – particularly its depiction of a Spanish missionary and Mexican “vaquero,” or cowboy, towering over an American Indian – is demeaning to American Indians.

Frank Happersberger’s pioneer monument, San Francisco, California, 1894. Lisa Allen.

Should the city take down part of this 125-year-old monument?

Many cities are removing or reinterpreting their Confederate monuments, with the understanding that they commemorate racism. But few Americans realize that pioneer monuments placed across the country are also racist.

As my research and forthcoming book on pioneer monuments since the 1890s show, most early pioneer statues celebrated whites dominating American Indians.

Confederate and pioneer monuments

Since at least 2015, cities across the United States have debated what to do with more than 700 Confederate monuments.

After the Civil War, grieving widows raised funds to place monuments to soldiers in southern cemeteries. But most statues of Confederate leaders and foot soldiers were put up around 1900 by heritage organizations to honor the “Lost Cause.”

The “Lost Cause” is the idea that that the Civil War began as a heroic defense against northern aggression. In fact, the Civil War was primarily fought to defend slavery.

In the past few years, cities such as New Orleans, Louisiana and Baltimore, Maryland have chosen to remove their Confederate statues. Activists tore down a Confederate soldier statue in Durham, North Carolina last year.

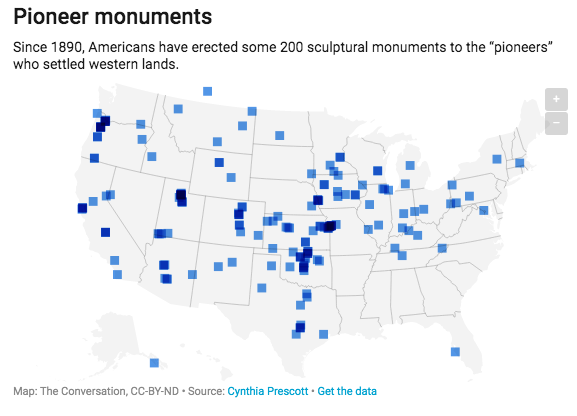

By contrast, there has been far less attention on the roughly 200 pioneer monuments erected for similar reasons around the same time.

The earliest pioneer monuments were put up in midwestern and western cities such as Des Moines, Iowa and San Francisco, California. They date from the 1890s and early 1900s, as whites settled the frontier and pushed American Indians onto reservations.

Those statues showed white men claiming land and building farms and cities in the West. They explicitly celebrated the dominant white view of the Wild West progressing from American Indian “savagery” to white “civilization.”

Deviations from that script produced public controversy. For example, Denver residents in 1907 vocally opposed prominent American sculptor Frederick MacMonnies’s plan for a pioneer monument. MacMonnies proposed a large stone pillar surrounded by bronze hunters, miners and settlers similar to San Francisco’s celebrated monument. MacMonnies’s model included a mounted Plains American Indian warrior atop the pillar to show American Indians yielding to white settlement.

But Denver residents expected the figure at the top of the pillar to represent the pinnacle of progress, like “Eureka,” the female figure representing the spirit of California on San Francisco’s monument.

Denver’s residents argued that the monument needed a white man on top, so MacMonnies revised his design, replacing the American Indian warrior with frontiersman and American Indian fighter Kit Carson, on horseback.

August Leimbach, Madonna of the Trail, Springfield, Ohio, 1928.

By the 1920s, whites controlled most western lands, and they stopped depicting American Indians in their pioneer monuments. New pioneer monuments from Maryland to California focused on western women. Pioneer mothers in sunbonnets stood for white “civilization” winning in the West. And they offered a conservative model of womanhood to contrast flappers wearing short dresses and bobbed hair and women’s growing sexual freedom.

More recent monuments, such as Goodland, Kansas’s “They Came to Stay” and Omaha, Nebraska’s “Pioneer Courage,” do not directly engage racial politics. As their titles suggest, these statues honor pioneer families’ grit, and they teach local history.

But these statues still represent a racist view, ignoring the cost of white settlement on Native lands. Like earlier monuments, they reinforce white dominance and erase ethnic diversity in the American West.

Pioneer monuments today

The recent debate about Confederate monuments has sparked some discussion of pioneer monuments in a few places. In April, Kalamazoo, Michigan removed its 1940 “Fountain of the Pioneers” because local residents disliked its depiction of a white settler looming over an American Indian.

After decades of protest, San Francisco debated taking down the depiction of a Spanish missionary towering over an American Indian from the 1894 pioneer monument.

In the 1990s, activists persuaded the city to place a plaque telling the dark side of California history in front of the statue. But today’s protesters argued that plaque, hidden by landscaping, is not enough. They want “Early Days” – if not the entire monument – taken down.

The San Francisco Arts Commission agrees, but the Board of Appeals blocked its removal in April.

On September 14, 2018, the “Early Days” statue was removed from the San Francisco monument and placed in storage. In April 2019, about 150 Native American leaders and youth from across California posed for photographs on the empty base where “Early Days” once stood. The photos will be part of the San Francisco Art Commission’s American Indian Initiative.

Each pioneer monument has its own history and local meaning. There is no one-size-fits-all solution. But communities are beginning to consider removing or reinterpreting these monuments to white conquest.

CYNTHIA PRESCOTT is an Associate Professor of History at the University of North Dakota.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Life on the border: Kurdish men in Kobani, Syria. Ahmed Mardnli/EPA

Syria Safe Zones: What is Driving the Unexpected Rapprochement Between the US and Turkey?

After years of rising tensions between Turkey and the US over the situation in northern Syria, an unexpected rapprochement has pulled the two countries back from possible conflict.

Relations between the two countries had deteriorated over Turkish opposition to the US alliance with Kurdish fighters in northern Syria, and Turkey’s recent purchase of a Russian air defence missile system. In response, the US kicked Turkey out of its F-35 fighter programme in July.

But in August, Turkey and US announced they would collaborate to establish safe zones along the Syrian-Turkish border, managed by a joint operations centre in Turkey.

Turkey has long demanded these buffer zones across its northern border with Syria to protect against possible assaults from the Kurdish People’s Protection Units, or YPG, which leads the Syrian Democratic Forces. The safe zone will effectively serve as a buffer between the YPG-controlled area and the Turkish border, and also combat the ongoing threat of Islamic State (IS) in the region.

The Turks and Americans are yet to agree on the size of the buffer zone – with Turkey pushing for it to be larger than the US wants – and it remains unclear who will police it. But in late August, YPG leaders agreed to withdraw their troops from towns near the Turkish border in what the Pentagon said was a sign of “good faith”.

But why has the US begun to condone Turkish action in northern Syria, and why now?

Deteriorating relations

Although Turkey and the US both sought to displace the regime of Bashar al-Assad in Syria, their priorities in the region changed over time. When the US launched its coalition against IS in 2014, Turkey joined reluctantly amid fears that the fight would harm the Syrian rebels fighting against the Assad regime.

But while Turkey remained suspicious over the presence of the YPG in northern Syria, the US allied with these very forces to defeat IS and to balance Iranian influence in the region.

When US President Donald Trump declared IS had been defeated in December 2018 and that American troops would withdraw from Syria, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan hurried to announce Turkish troops could replace the Americans in the region. Erdoğan has repeatedly stressed that Turkey will not harm Syrian Kurdish civilians, but rather target militant groups in the region, including the YPG which it sees as linked to the Kurdish separatist Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK.

Similar styles. Ahmed Mardnli/EPA

After the reaction in Washington to the decision to withdraw from Syria – which caused resignations and criticism from senior politicians – Trump reversed his decision. In early January the US government said it would not withdraw until the Turkish government guaranteed it would not to attack Syrian Kurds who had been part of the alliance fighting against IS. Turkey has not given this guarantee.

Mistrust has festered over alleged links with each of the allies’ foes, namely Turkey with IS fighters and the US with the YPG. Amid the tensions, the US embassy in Ankara remained vacant.

Pulling back from conflict

There are three reasons for the current rapprochement. The first is a growing desire from both sides to avoid conflict between their military personnel in the region. In 2018, Erdoğan threatened that any US soldiers who stood in the way of the Turkish invasion of Afrin, a Syrian enclave in northern Syria, with an “Ottoman slap”.

Ankara now seems more willing to collaborate with Washington. The welcome extended to the new American ambassador to Turkey, David Satterfield, at the presidential palace on August 28, signalled the allies are looking to build bridges.

The second is that Assad’s forces are encroaching into the last remaining opposition stronghold in Idlib with their Russian allies. Turkey is likely to face another stream of Syrian refugees across to its borders. The search for an agreement over safe zones in northern Syria comes to the fore as Erdoğan feels the brunt of his pro-refugee politics at home.

Since its invasion of Afrin, Turkey has sought to settle Syrian refugees in safe zones in the province. The newly proposed safe zones are likely to see a push for further refugee returns. Similar goals of returning refugees are also pushing other peace efforts in the region – notably between the US and Taliban in Afghanistan.

The third reason is more personal. Erdoğan says Trump has a feel for him. Both leaders are celebrity politicians, with their families at the foreground of their politics. They share anti-establishment mentalities, and use religious references and nationalist discourses to appeal to their supporters.

The Russian factor

Hanging over this rapprochement, however, is the issue of the Russian missiles. So far the Trump administration has not imposed economic sanctions on Turkey over the issue, despite criticisms from Congress over the risks it poses to NATO security. Turkey said it would not activate the missiles until April 2020, allowing negotiation channels with the US over northern Syria to remain open.

Turkey has been a proactive voice against military assaults by the Assad regime in northern Syria, yet it has remained quiet on the Russian-Syrian alliance in the region. Since the failed coup attempt in 2016, the Erdoğan regime has been increasingly pro-Putin, signalling it is turning its back on its traditional Western allies.

That’s why it’s so significant that Turkey and the US are searching for collaboration in the region despite their policy differences. In the Turkish case, this could be a way to enhance its buffer as Assad forces regain the northern provinces from the rebels. In the American case, it could be to expand its alliances to offset Russian and Iranian influence in the future Assad-ruled Syria.

TARIK BASBUGOGLU is a PhD Candidate at Glasgow Caledonian University.

UMUT KORKUT is a Chair professor at Glasgow Caledonian University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

A Crisis of Violence Pushes Honduran Women to the U.S. Border

For women facing rampant femicide and rape in Honduras, the risks of a treacherous trip across the border are minor compared to the dangers of remaining at home.

High rates of violence against women in Honduras has been attributed to a culture of machismo. Paul Lowry via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 2.0

Yo no quiero ser violada.

I do not want to be raped.

So read the signs plastered across walls and doors in the cities of Honduras. Simple black lettering is inscribed beneath a pair of thickly lashed eyes, with the eyebrows above turned downwards in an expression of anger—or, more accurately, indignation—at the dangerous injustices Honduran women face every day.

Honduras has been called the most dangerous place on Earth to be a woman, and with good reason: As of 2015, the Central American nation ranked alongside war-torn countries like Syria and Afghanistan for the highest rates of violent deaths among women. Although the overall murder rate of Honduras, which has long been wracked by drug- and gang-related violence, has declined in recent years, murder remains the second-leading cause of death for women of childbearing age.

In 2014, a high-profile “femicide”—the murder of a woman because she is a woman—rocked the nation and brought its murder rates into the international spotlight. Nineteen-year-old Miss Honduras winner Maria Jose Alvarado, just days from departing for London to compete for the title of Miss World, was brutally murdered and buried in a shallow grave in a riverbank. Authorities surmised that her sister’s boyfriend, 32-year-old Plutarco Ruiz, shot his girlfriend, Sofia Trinidad, before opening fire on Maria Jose as she attempted to flee. The ensuing investigation yielded the sisters’ bodies within a week, but their mother, Teresa Muñoz, believed it would not have happened at all if Maria Jose had not been famous: “Here in Honduras, women aren’t worth anything,” she told ABC News.

In 2013, the year before Maria Jose’s violent death, statistics showed that 636 women were murdered during the year, one every 13.8 hours. Most victims lived in urban areas, particularly San Pedro Sula and the Central District—in fact, 40 percent of all murders of women could be traced to those two areas. Nearly half of all women targeted annually were young, with the 20–24 age range being the most at risk. And murder is far from the only danger facing Honduran women. Rape, assault, and domestic violence are also rampant, and perpetrators enjoy near-total impunity: In 2014, the UN found that 95 percent of sexual violence and femicide cases were never investigated.

San Pedro Sula, a city with high rates of femicide. Gervaldez. CC BY-SA 4.0, CC BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 2.5, CC BY-SA 2.0, CC BY-SA 1.0

Honduras’ shocking levels of violence against women can be traced in part to harmful attitudes bubbling below the surface. Suyapa Martínez, a local feminist and co-director of the Center for Women’s Studies—Honduras, points to “machismo,” a Spanish term describing a society built by men “who consider themselves to be the owners of women’s bodies.” In such a society, women have historically lacked political power: Only about half of Honduran women work outside the home, and when they do, they earn just half of what their male colleagues bring in.

Meanwhile, those ostensibly tasked with protecting all Honduran citizens—women included—have done little to mitigate the crisis. A 2015 report from the UN special rapporteur on violence against women concluded that the administration has paid “minimal attention” to gender empowerment and implemented only “ineffective measures” to address social reform. And in many cases, the government inflames the problem by limiting women’s options after sexual violence: Emergency contraception is completely banned, as is abortion, even in the case of rape, incest, or threat to the mother’s life. Women who seek abortion can receive a prison sentence of up to six years. These strict rules stem from the stranglehold of the Catholic and Evangelical churches, who have resisted even minor liberalizations to legislation—even after the UN joined with other human rights groups in 2017 to call for the allowance of abortion in cases of rape, incest, or possibility fatality. To make matters worse, the government is expected to decrease the penalty for violence against women later this year to between one and four years in prison.

Trapped in a repressive society and seeing little hope for a safer future, huge influxes of women and children have embarked on the treacherous journey to America’s southern border. In what the UN has called an “invisible refugee crisis,” women from the Northern Triangle—which includes Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala—have been fleeing in droves, with more than half listing violence as their reason for requesting entry to the United States. Lori Adams, director of the U.S.-based Immigration Intervention Project at Sanctuary for Families, told Politico, “Women are leaving with no other option but to flee north, even knowing that the journey itself might be life-threatening, but knowing it’s a near certainty that they will be killed if they remain.”

Migration office in Honduras. KriKri01. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Yet even if women survive the trek north, their hopes are often dashed when they reach the border. According to researchers at Syracuse University, the percentage of asylum applicants denied by U.S. immigration courts has been increasing since 2012, reaching 65 percent in 2018. That year, prospects for Hondurans were particularly grim, with judges granting just 21 percent of asylum cases. And as of mid-August, new policies from the Trump administration will privilege green-card applicants—immigrants aiming to become naturalized citizens—who are educated and monied while denying those who are considered likely to rely on government welfare programs. Given the financial dynamics of Latin America, the new rule will almost certainly affect Honduran women seeking safety in the United States. Dario Aguirre, a Denver-based immigration lawyer, told the New York Times that Trump’s policy gives officers carte blanche to deny green cards to many working-class immigrants from less developed countries, such as El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. Thus, another option is ripped from the hands of already desperate Honduran women—and until the U.S. government or Honduran officials enact substantive change, their eyes will stay wide open like the posters on the walls, watching keenly for danger.

TALYA PHELPS hails from the wilds of upstate New York, but dreams of exploring the globe. As former editor-in-chief at the student newspaper of her alma mater, Vassar College, and the daughter of a journalist, she hopes to follow her passion for writing and editing for many years to come. Contact her if you're looking for a spirited debate on the merits of the em dash vs. the hyphen.

This Is the Only Shelter for Refugees in NYC

Edafe Okporo is the director of the only shelter in New York City that provides housing for asylum seekers, refugees and migrants. He knows what it’s like to arrive in the U.S. with nowhere to go. Okporo left Nigeria seeking asylum after he was attacked by a mob because of his sexual orientation. With the hope of a better life, he came to the U.S., but soon realized he faced another battle. Refugees can undergo harsh treatment, having to navigate complex asylum law and face time in detention centers. Still, he persevered, and built a life for himself. Now, Okporo is helping others do the same.

The Threat to America that’s been Growing Inside America

While the Middle East and the border crisis get all the attention, Charlottesville and El Paso remind us that America’s worst threat is right here at home.

White supremacists gathered for the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. By Anthony Crider. CC by 2.0.

August 12th 2017, fresh out of my first year at the University of Virginia, I sat in front of my TV horrified, watching white supremacists marching through a place I had recently starting calling home. Headlines on every major paper ran with Trump’s quote regarding “fine people on both sides.”

When classes started in the fall, my peers and I returned to Charlottesville deeply unsettled by what had happened on our grounds. Our community was rocked to its core. However, the rest of the world quickly moved on without us.

The past two years, this weekend has marked a time for remembrance, but also caution and fear in Charlottesville. The dates, August 11th and 12th, have become something of the towns very on 9/11, and the police presence during these two days isn’t easy to ignore. The events that took place to years ago are on our minds, however, not on the mind of the nation.

The march on Charlottesville was the last time I saw white supremacy dominate all the major headlines, that is, until this weekend’s mass shooting in El Paso. We, as a nation, let ourselves become distracted and forgetful of a real problem that’s been growing in the heart of our country. We can point to how the nation has so eagerly embraced the narrative of the “dangerous outsider” to explain why.

A decade ago, the Department of Homeland Security released a report on the growing threat of right wing extremism, correctly predicting “the potential emergence of terrorist groups or lone wolf extremists capable of carrying out violent attacks.” However, this warning was not given serious merit by the Trump administration. President Trump’s transition team made it clear to the DHS that it wanted to focus on Islamic terrorism and reorient programs meant to counter violent extremism to exclusively target international threats like al-Qaeda and ISIL. These Islamic terrorist groups have stayed in the headlines, despite the fact they no longer pose a serious domestic threat. It should come as no surprise that this June the FBI reported a significant rise in white supremacist domestic terrorism in recent months.

President Trump’s rhetoric has also turned American’s attention away from the alt-right matter at hand, and turned our attention to what he would call an “infestation.” Searching through theTrump Twitter Archive, I failed to find one mention of domestic terrorism, white nationalists or the growing menace they pose to our country. After all, why shouldn’t Trump protect his loyal voter base? It’s no secret that white nationalists are Trump supporters; alt right leaders have even been spotted at his rallies.

President Trump says immigrants “infest” our country. Via Twitter. June 19, 2018.

The president has protected these terrorists by turning the national discussion elsewhere -the southern border. As a result, liberals have kept themselves busy investigating the disgusting conditions of border control centers and “children in cages,” while conservatives call for further border restrictions. These leaves no one time for anyone to wage war against the real domestic threat --white supremacy.

Trump denounced “racist hate” Monday after the shooting this weekend. He blamed violent video games, mental health and, ironically, internet bigotry from prompting the Dayton and El Paso attacks. He failed to make mention of any real action that might be taken against white supremacist terrorism, let alone endorse gun law reform.

Had the attackers been Black, Hispanic or Middle Eastern, the White House would surely be taking extreme action. However, just like during the aftermath of Charlottesville, nothing serious is being done to combat alt-right violence.

Now,in light of the two year anniversary, I can’t help but wonder if our country truly took notice of the event that shook our little community two years ago. I still pass by the street where Heather Heyer was killed by a domestic terrorist who drove his car into a crowd of people two years ago. The street, now named Heather Heyer Way, remains adorned with chalk writing, flowers and crosses dedicated to her memory. How many more memorials must we lay in El Paso, and the rest of the world, before we address the white supremacist threat?

EMILY DHUE is a third year student at the University of Virginia majoring in media. She is currently studying abroad in Valencia, Spain. She's passionate about writing that makes an impact, and storytelling through digital platforms.

Scientists Have Discovered a Large Freshwater Aquifer off the Northeast Coast of the U.S.

The discovery could point to similar reservoirs adjacent to water starved areas.

Photo of Bradley Beach, New Jersey, by Ryan Loughlin on Unsplash.

It’s rare to hear good news on the climate, but occasionally we get lucky. Last month, scientists led by Chloe Gustafson of Comumbia’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory published an article in the Scientific Reports journal. Their discovery? A large freshwater aquifer located off the northeast coast of the U.S.

The possibility of an aquifer was initially discovered during offshore oil drilling in the 1970’s, when oil companies noticed that they occasionally hit pockets of freshwater in the north Atlantic. There was no consensus at the time on whether these were merely isolated areas or if they pointed to something larger. Then, in the late 90’s, Kerry Key, a geophysicist who co-authored the study, began working with oil companies to develop electromagnetic imaging techniques that could help them better examine the sea floor for oil. He later adapted the technology to look for freshwater deposits.

More recently, Key and his colleagues spent 10 days on board a research vessel, charting areas where freshwater had been discovered. “We knew there was freshwater down there in isolated places, but we did not know the extent or geometry,” Chloe Gustafson explained in a press release.

According to the report, the aquifer spans from New Jersey to Martha’s Vineyard, and carries an estimated 670 cubic miles of water lying beneath sponge-like sediment which separates it from the saline ocean water. “These aren’t open caverns or lakes underneath the seafloor,” Gustafson told NBC, “this is water trapped within the pores of rocks, so it’s sort of like a water-soaked sponge.” The reservoir reaches from 600 to 1,200 feet below the seafloor. For comparison, the aquifer carries more than half the water of Lake Michigan.

While the discovery of a large freshwater source is exciting under any circumstance, it is unlikely to have a major impact on access to water in New England, as the area is receives a good amount of rainwater. While the aquifer could be pumped, and the water exported to more arid areas, such efforts would be expensive and unsustainable. Graham Fogg, hydrogeology professor at the University of California Davis, told NBC that “there’s a limit to how much you can pump sustainably. It would take a long time to empty these aquifers, but we wouldn’t want to get to a point where we’ve pumped so much that we’ve exhausted the supply.”

The impact of the study lies in the possibility that such reservoirs could exist off the coasts of drier, more arid places that are prone to water shortage. NBC reports that pointers to the possibility of aquifers have already been found off the coasts of Greenland, South Carolina, and California.

As we experience the effects of climate change, and especially in light of the water shortage in Chennai, this is indeed good news.

EMMA BRUCE is an undergraduate student studying English and marketing at Emerson College in Boston. While not writing she explores the nearest museums, reads poetry, and takes classes at her local dance studio. She is passionate about sustainable travel and can't wait to see where life will take her.

The U.S.-Mexico border, pictured here from the air, is receiving more attention as Afircan migrants cross it to seek asylum in the U.S. WikiImages. CC0.

African Migrants Journey to U.S. Border in Search of Asylum

African migrants, mostly from Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo, are beginning to congregate at U.S. border cities, especially San Antonio, Texas and Portland, Maine, seeking asylum.

Many are flying to South America and joining fellow migrants in traveling well-trodden paths across Central America to the U.S.-Mexico border, since they have been proven to work. Europe has also recorded a sharp drop in the number of African migrants and refugees who have reached its border.

Migrants who do try to make the treacherous journey across the Meditteranean often never make it there. The EU began a regional disembarkation policy last June, which named Libya as the new center for processing refugee and asylum applications for those seeking to leave Africa for Europe. However, asylum-seekers stopped by the EU-trained and equipped Libyan Coast Guard are brought back to civil war-torn Libya. Roughly 700,000 refugees are in local detention centers, facing starvation, sexual violence, and torture, according to Foreign Policy. There is also the possibility of being captured by Libyan smugglers. Many people have either gone missing or died. Official numbers have not been released.

Niger is taking in refugees so they don’t need to stay in Libya while they wait to be fully resettled in a new host country, but is only accepting a limited number of people due to its own low poverty rate. The resettlement process can take anywhere from 8 to 12 months. Often, Africans are finding that it is easier to avoid the Mediterranean altogether, due to the trouble Libya’s smugglers and detention centers can cause. 12 countries have so far pledged to help resettle the refugees, though the U.S. is not one of them.

American border agents first started noticing the high numbers at the Del Rio border station in southern Texas last month. According to Time, the sheer number of people is overwhelming. “When we have 4,000 people in custody, we consider it high,” Customs and Border Patrol’s commissioner John Sanders said, according to the BBC. “If there’s 6,000 people in custody, we considered it a crisis. Right now, we have nearly 19,000 people in custody. So it’s just off the charts.”

According to NPR, one such refugee journey involved a family of six flying to Ecuador and traveling by foot across Central America to eventually end up in the border city of Portland, Maine. They were fleeing civil unrest in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Their destination was a makeshift border shelter—a converted sports arena—that was described as “paradise” by the father. Randy Capps, the director of research for U.S. programs at the Migration Policy Institute, said, "That journey through Central America and Mexico has been facilitated by these large migrant caravans, by more sophisticated and faster smuggling routes, and it's an easier journey from Guatemala onward than it has been in the past."

Once they get through the border station, migrants are brought to relief shelters. Staff have been bringing in Swahili and French translators. Portland city officials are hopeful for the future, seeing the migrants as a necessary part of the future workforce, especially since the city has an elderly population. Still, the influx has stressed the city in terms of space. The converted arena currently houses over 200 people.

Volunteers assist at the shelter, offering food and medical supplies and playing games with the children. Donations of both money and supplies have been pouring in. Maine governor Janet Mills has stated that she wants the state to help out, saying that Maine’s residents have a “proud tradition” of caring for their neighbors.

NOEMI ARELLANO-SUMMER is a journalist and writer living in Boston, MA. She is a voracious reader and has a fondness for history and art. She is currently at work on her first novel and wants to eventually take a trip across Europe.

Entry to Mount Rushmore along the Avenue of Flags. Xiao Fang/Wikimedia, CC BY

Visiting National Parks Could Change Your Thinking About Patriotism

When I took a post-college job as a seasonal ranger at Grand Teton National Park 23 years ago, I noticed right away that my “Smokey Bear” hat carried some serious emotional baggage. As I later wrote in my book, “Reclaiming Nostalgia: Longing for Nature in American Literature,” park visitors saw the hat as an icon of tradition and romance, a symbol of a simpler era long gone.

For many Americans the physical grandeur of parks like Grand Teton, Yosemite and Yellowstone also inspires patriotic pride. Twenty-first-century patriotism is a touchy subject, increasingly claimed by America’s conservative right. But the national park system is designed to be democratic – protecting lands that belong to the public for all to enjoy – and politically neutral. The parks are spaces where love of country can be shared by all.

But some sites send more complex messages. In my new book, “Memorials Matter: Emotion, Environment, and Public Memory at American Historical Sites,” I explore how patriotism plays out at sites where education, not recreation, is the priority. To research it I visited seven memorials to see how their structures and natural landscapes inspire patriotism and other emotions.

For me, and I suspect for many, national memorials elicit conflicting feelings: pride in our nation’s achievements, but also guilt, regret or anger over the costs of progress. Patriotism, especially at sites of shame, can be unsettling – and I see this as a good thing. In my view, honestly confronting the darker parts of U.S. history as well as its best moments is good for tourism, for patriotism and for the nation.

Whose history?

Patriotism has roots in the Latin “patriotia,” meaning “fellow countryman.” It’s common to feel patriotic pride in U.S. technological achievements or military strength, but Americans also glory in the diversity and beauty of our natural landscapes. That kind of patriotism, I think, has the potential to be more inclusive, less divisive and more socially and environmentally just.

National memorials can summon more than one kind of patriotism. Take Mount Rushmore, which was designed explicitly to evoke national pride. Tourists walk the Avenue of Flags, marvel at the labor required to carve four U.S. presidents’ faces out of granite and applaud when rangers invite military veterans onstage during visitor programs. Patriotism at Rushmore centers on labor, progress and the “great men” that the site describes as founding, expanding and defending the U.S.

But there are other perspectives. Viewed from the Peter Norbeck Overlook, a short drive from the main site, the faces of Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt and Lincoln are tiny elements embedded in the expansive Black Hills region. The Black Hills were and still are a sacred place for Lakota peoples that they never willingly relinquished. Viewing Mount Rushmore this way puts those rock faces in context and raises questions about history and justice.

Mt. Rushmore National Memorial in South Dakota, viewed from the Peter Norbeck Overlook. Jennifer Ladino, CC BY-ND

Some national monuments conduct reenactments to help visitors relive the past and feel a sense of history and authenticity. At Golden Spike National Historic Site in Utah, tourists can view replica steam locomotives and watch a reenactment of driving the spike that completed the first transcontinental railroad.

This park also ties patriotism to technology, labor, unity and progress. But it downplays countless lives lost during construction, including a disproportionate number of Chinese laborers. There’s an implied whiteness to the patriotism here, although those Chinese workers are receiving belated recognition.

Away from the main complex, however, visitors can see an impressive natural landscape carved by geologic forces. At “Chinaman’s Arch,” they can read about ancient Lake Bonneville, which once covered 20,000 square miles. Against the backdrop of geologic time, human labor and technological power look less impressive. A different feeling of patriotism emerges here that can embrace the physical country all Americans share.

Chinese railroad workers in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains, photographed between 1865 and 1869. Alfred Hart/Library of Congress

Sites of shame

Even sites where visitors are meant to feel remorse leave some room for patriotism. But at places like Manzanar National Historic Site in California – one of 10 camps where over 110,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II – natural and textual cues prevent any easy patriotic reflexes.

Reconstructed guard towers and barracks help visitors perceive the experience of being detained. I could imagine Japanese-Americans’ shame as I entered claustrophobic buildings and touched the rough straw that filled makeshift mattresses. Many visitors doubtlessly associate mountains with adventure and freedom, but some incarcerees saw the nearby Sierra Nevada as barricades reinforcing the camp’s barbed wire fence.

Rangers play up these emotional tensions on their tours. One ranger positioned a group of schoolchildren atop what were once latrines, and asked them: “Will it happen again? We don’t know. We hope not. We have to stand up for what is right.” Instead of a self-congratulatory sense of being a good citizen, Manzanar leaves visitors with unsettling questions and mixed feelings.

Young tourists experience the humiliating lack of privacy at Manzanar National Historic Site. Jennifer Ladino, CC BY-ND

Humble patriotism

Visiting and writing about these sites made me consider what it would take to recast patriotism as collective pride in the United States’ diverse landscapes and peoples. I believe one essential ingredient is compassion. Recent controversies over Confederate monuments showed that many Americans were unwilling to imagine how public memorials could be offensive or traumatic for others.

Greater clarity about value systems can also help. Psychologists have found striking differences between the moral frameworks that shape liberals’ and conservatives’ views. Conservatives generally prioritize purity, sanctity and loyalty, while liberals tend to value justice in the form of concerns about fairness and harm. In my view, patriotism could bridge the apparent gap between these moral foundations.

My research suggests that visits to memorial sites are helpful for recognizing our interdependence with each other, as inhabitants of a common country. In her recent book, “The Hour of Land: A Personal Topography of America’s National Parks,” Terry Tempest Williams wonders, “What is the relevance of our national parks in the twenty-first century – and how might these public commons bring us back home to a united state of humility?” Places like Manzanar and Golden Spike are part of a common heritage embedded in public lands. It’s our responsibility as citizens to visit these places with both pride and humility.

JENNIFER LADINO is an Associate Professor of English, University of Idaho.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Hawaii’s Long Legacy of Lei Making

In Hawaii, there’s no better way to say and share aloha than with a lei. The floral craft, which dates back to traditional times, may seem straightforward to outsiders, but it comes in many forms created across the Islands. Travel to the island of Oahu, where three master artisans want to introduce you to the lei’s vibrant past and thriving present.

Asylum Seekers in Tlaquepaque, Jalisco. Daniel Arauz. CC 2.0

The LGBTQ Migrant Caravan that Sought Asylum in the US

LGBTQ migrants from Central America seeking asylum in the US faced hardship and discrimination not only from gangs that prey on migrants as they travel, but also from their fellow travelers. They were a part of a “caravan” of 3,600 asylum seekers, that started to journey from San Pedro Sula, Honduras in October 2018, traveled through Mexico, and reached the Northern Mexican city Tijuana, bordering the US, in November 2018. The members of the caravan were escaping all kinds of violence in their home countries of Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador.

The LGBTQ group of the caravan traveled together, in a group of around 80, to provide safety in numbers. They were subject to verbal abuse from all ends, and were even denied food and access to showers by other members of the caravan and other local groups. They weren’t about to receive a warm welcome from the US either, as President Trump frequently targeted the group of migrants during the 2018 Midterm Elections.

Migrant caravans from Central America travel through Mexico in the hopes of passing through the US-Mexico border in search for freedom. Many don’t make it in, and those who do are held at the border.

The migrants were fleeing discrimination and persecution of LGBTQ people in their own countries. They were threatened to be killed or tortured because of their sexuality. They embarked on a journey to the US in the hopes of obtaining a new life, with new opportunities to make a living in a more accepting community.

The LGBTQ group of the caravan stuck together and looked out for each other, for fear of being assaulted. They slept in abandoned, dilapidated hotels rather than outside, where they are subject to more violence. To prevent attacks, human rights workers have sent two people in green vests to travel with the caravan. These groups found the migrants through strong media coverage and decided to help.

They trekked over 1,000 miles in a month. Most of the traveling is done by foot when they are unable to hitch a ride on buses, trucks, or tractor-trailers.

When they finally reached Tijuana, they were subject to anger from the local residents, who were angry that they were staying in a house in their neighborhood.

They waited at detention centers in Texas for a very long time after crossing the border. These detention centers had no experience in housing transgender women. However, recently, it was announced that ten transgender women have won their asylum cases, and were allowed to leave the detention center. The immigrant rights group RAICES helped to provide legal support for the migrants to win their cases.

ELIANA DOFT loves to write, travel, and volunteer. She is especially excited by opportunities to combine these three passions through writing about social action travel experiences. She is an avid reader, a licensed scuba diver, and a self-proclaimed cold brew connoisseur.

Protecting Our Oceans from Ghost Traps

At any given time, there are thought to be over 360,000 tons of loose fishing gear floating through our oceans. These disregarded pieces of debris are a danger to our aquatic ecosystems, trapping fish, turtles, birds and even whales. Kurt Lieber assembled the Ocean Defender Alliance, a group of volunteer divers cleaning California’s coasts of ghost nets and traps.

A steel wall along the U.S. border near Tecate, California, cuts across Mount Cuchame, a site sacred to the Kumeyaay people. Reuters/Adrees Latif

For Native Americans, US-Mexico Border is an ‘Imaginary Line’

Immigration restrictions were making life difficult for Native Americans who live along – and across – the U.S.-Mexico border even before President Donald Trump declared a national emergency to build his border wall.

The traditional homelands of 36 federally recognized tribes – including the Kumeyaay, Pai, Cocopah, O’odham, Yaqui, Apache and Kickapoo peoples – were split in two by the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and 1853 Gadsden Purchase, which carved modern-day California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas out of northern Mexico.

Today, tens of thousands of people belonging to U.S. Native tribes live in the Mexican states of Baja California, Sonora, Coahuila and Chihuahua, my research estimates. The Mexican government does not recognize indigenous peoples in Mexico as nations as the U.S. does, so there is no enrollment system there.

Still, many Native people in Mexico routinely cross the U.S.-Mexico border to participate in cultural events, visit religious sites, attend burials, go to school or visit family. Like other “non-resident aliens,” they must pass through rigorous security checkpoints, where they are subject to interrogation, inspection and rejection or delay.

Many Native Americans I’ve interviewed for anthropological research on indigenous activism call the U.S.-Mexico border “the imaginary line” – an invisible boundary created by colonial powers that claim sovereign indigenous territories as their own.

A border wall would further separate Native peoples from friends, relatives and tribal resources that span the U.S.-Mexico border.

Homelands divided

Tribal members say that many Native Americans in the U.S. feel detached from their relatives in Mexico.

“The effect of a wall is already in us,” Mike Wilson, a member of the Tohono O'odham Nation, who lives in Tucson, Arizona, told me. “It already divides us.”

The Tohono O’odham are among the U.S. federal tribes fighting the government’s efforts to beef up existing security with a border wall. In late January, the Tohono O'odham, Pascua Yaqui and National Congress of Indian Americans met to create a proposal for facilitating indigenous border crossing.

The Tohono O'odham already know how life changes when traditional lands are physically partitioned.

Verlon Jose, vice-chairman of the Tohono O'odham Nation, at the border barrier that traverses the Tohono O'odham reservation in Chukut Kuk, Ariz., in 2017. Reuters/Rick Wilking

By U.S. law, enrolled Tohono O’odham members in Mexico are eligible to receive educational and medical services in Tohono O'odham lands in the U.S.

That has become difficult since 2006, when a steel vehicle barrier was built along most of the 62-mile stretch of U.S.-Mexico border that bisects the Tohono O’odham Nation.

Previously, to get to the U.S. side of Tohono O’odham territory, many tribe members would simply drive across their land. Now, they must travel long distances to official ports of entry.

One Tohono O'odham rancher told The New York Times in 2017 that he must travel several miles to draw water from a well 100 yards away from his home – but in Mexico.

And Pacific Standard magazine reported in February 2019 that three Tohono O'odham villages in Sonora, Mexico, had been cut off from their nearest food supply, which was in the U.S.

Native rights

Land is central to Native communities’ historic, spiritual and cultural identity.

Several international agreements – including the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples – confirm these communities’ innate rights to draw on cultural and natural resourcesacross international borders.

An 1894 map of indigenous North American languages shows how Native homelands span modern-day national borders.British Library

The United States offers few such protections.

Officially, various federal laws and treaties affirm the rights of federally recognized tribes to cross between the U.S., Mexico and Canada.

The Jay Treaty of 1794 grants indigenous peoples on the U.S.-Canada border the right to freely pass and repass the border. It also gives Canadian-born indigenous persons the right to live and work in the United States.

The American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 says that the U.S. will protect and preserve Native American religious rights, including “access to sacred sites” and “possession of sacred objects.” And the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act protects Native American human remains, burial sites and sacred objects.

United States law also requires that federally recognized sovereign tribal nations on the U.S.-Mexico border must be consulted in federal border enforcement planning.

In practice, however, the free passage of Native people who live across both the United States’ northern or southern border is curtailed by strict identification laws.

The United States requires anyone entering the country to present a passport or other U.S.-approved identification confirming their citizenship or authorization to enter. The Real ID Act of 2005 allows the Department of Homeland Security secretary to waive any U.S. law – including those protecting indigenous rights – that may impede border enforcement.

Several standard U.S. tribal identification documents – including Form I-872 American Indian Card and enhanced tribal photo identification cards – are approved travel documents that enable Native Americans to enter the U.S. at land ports of entry.

Arbitrary identity tests

Only the American Indian Card, which is issued exclusively to members of the Kickapoo tribes, recognizes indigenous people’s right to cross the border regardless of citizenship.

According to the Texas Band of Kickapoo Act of 1983, “all members of the Band” – including those who live in Mexico – are “entitled to freely pass and repass the borders of the United States and to live and work in the United States.”

The majority of indigenous Mexicans wishing to live or work in the United States, however, must apply for immigrant residence and work authorization like any other person born outside of the U.S. The relevant tribal governments in the U.S. may also work with Customs and Border Patrol to waive certain travel document requirements on a case-by-case basis for short-term visits of Native members from Mexico.

Since border patrol agents have expansive discretionary power to refuse or delay entries in the interest of national security, its officers sometimes make arbitrary requests to verify Native identity in these cases.

Such tests, my research shows, have included asking people to speak their indigenous language or – if the person is crossing to participate in a Native ceremony – to perform a traditional song or dance. Those who refuse these requests may be denied entry.

Border agents at both the Mexico and Canada borders have also reportedly mishandled or destroyed Native ceremonial or medicinal items they deem suspicious.

“Our relatives are all considered ‘aliens,’” said the Yaqui elder and activist José Matus. “[T]hey’re not aliens. … They’re indigenous to this land.”

“We’ve been here since time immemorial,” he added.

CHRISTINA LEZA is an Associate Professor of Anthropology at Colorado College.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Alaska

Tim Kellner recorded this video to display his experience traveling in Alaska. In regard to his experience, Tim states “When I was a kid I would stare up at the giant stuffed grizzly bear in the Buffalo Science Museum and imagine seeing it alive and in the wild. That dream finally came true. I can't even begin to describe with words my experiences in Alaska so hopefully this video will capture just a small piece.” The music in the video is also by Tim.

From New York

Leonard Witte had the chance to travel around the world to capture some of the biggest cities of the world. He decided to create his own version for each city - this is number one! The film is a mixture of audiovisual moments he experienced and voices from real New Yorkers telling about their city.

City Farm is a working sustainable farm that has operated in Chicago for over 30 years. Linda from Chicago/Wikimedia, CC BY

How Urban Agriculture Can Improve Food Security in US Cities

During the partial federal shutdown in December 2018 and January 2019, news reports showed furloughed government workers standing in line for donated meals. These images were reminders that for an estimated one out of eight Americans, food insecurity is a near-term risk.

In California, where I teach, 80 percent of the population lives in cities. Feeding the cities of the nine-county San Francisco Bay Area, with a total population of some 7 million involves importing 2.5 to 3 million tons of food per day over an average distance of 500 to 1,000 miles.

This system requires enormous amounts of energy and generates significant greenhouse gas emissions. It also is extremely vulnerable to large-scale disruptions, such as major earthquakes.

And the food it delivers fails to reach 1 of every 8 people in the region who live under the poverty line – mostly senior citizens, children and minorities. Access to quality food is limited both by poverty and the fact that on average, California’s low-income communities have 32.7 percent fewer supermarkets than high-income areas within the same cities.

Many organizations see urban agriculture as a way to enhance food security. It also offers environmental, health and social benefits. Although the full potential of urban agriculture is still to be determined, based on my own research I believe that raising fresh fruits, vegetables and some animal products near consumers in urban areas can improve local food security and nutrition, especially for underserved communities.

The growth of urban agriculture

Urban farming has grown by more than 30 percent in the United States in the past 30 years. Although it has been estimated that urban agriculture can meet 15 to 20 percent of global food demand, it remains to be seen what level of food self-sufficiency it can realistically ensure for cities.

One recent survey found that 51 countries do not have enough urban area to meet a recommended nutritional target of 300 grams per person per day of fresh vegetables. Moreover, it estimated, urban agriculture would require 30 percent of the total urban area of those countries to meet global demand for vegetables. Land tenure issues and urban sprawl could make it hard to free up this much land for food production.

Other studies suggest that urban agriculture could help cities achieve self-sufficiency. For example, researchers have calculated that Cleveland, with a population of 400,000, has the potential to meet 100 percent of its urban dwellers’ fresh vegetable needs, 50 percent of their poultry and egg requirements and 100 percent of their demand for honey.

Can Oakland’s urban farmers learn from Cuba?

Although urban agriculture has promise, a small proportion of the food produced in cities is consumed by food-insecure, low-income communities. Many of the most vulnerable people have little access to land and lack the skills needed to design and tend productive gardens.

Cities such as Oakland, with neighborhoods that have been identified as “food deserts,” can lie within a half-hour drive of vast stretches of productive agricultural land. But very little of the twenty million tons of food produced annually within 100 miles of Oakland reaches poor people.

Paradoxically, Oakland has 1,200 acres of undeveloped open space – mostly public parcels of arable land – which, if used for urban agriculture, could produce 5 to 10 percent of the city’s vegetable needs. This potential yield could be dramatically enhanced if, for example, local urban farmers were trained to use well-tested agroecological methods that are widely applied in Cuba to cultivate diverse vegetables, roots, tubers and herbs in relatively small spaces.

In Cuba, over 300,000 urban farms and gardens produce about 50 percent of the island’s fresh produce supply, along with 39,000 tons of meat and 216 million eggs. Most Cuban urban farmers reach yields of 44 pounds (20 kilograms) per square meter per year.

An organic farm in Havana, Cuba, that produces outputs averaging 20 kilograms (44 pounds) per square meter per year without agrochemical inputs. Miguel Altieri, CC BY-ND

If trained Oakland farmers could achieve just half of Cuban yields, 1,200 acres of land would produce 40 million kilograms of vegetables – enough to provide 100 kilograms per year per person to more than 90 percent of Oakland residents.

To see whether this was possible, my research team at the University of California at Berkeley established a diversified garden slightly larger than 1,000 square feet. It contained a total of 492 plants belonging to 10 crop species, grown in a mixed polycultural design.

In a three-month period, we were able to produce yields that were close to our desired annual level by using practices that improved soil health and biological pest control. They included rotations with green manures that are plowed under to benefit the soil; heavy applications of compost; and synergistic combinations of crop plants in various intercroppingarrangements known to reduce insect pests.

Research plots in Berkeley, Calif., testing agroecological management practices such as intercropping, mulching and green composting. Miguel Altieri, CC BY-ND

Overcoming barriers to urban agriculture

Achieving such yields in a test garden does not mean they are feasible for urban farmers in the Bay Area. Most urban farmers in California lack ecological horticultural skills. They do not always optimize crop density or diversity, and the University of California’s extension program lacks the capacity to provide agroecological training.

The biggest challenge is access to land. University of California researchers estimate that over 79 percent of the state’s urban farmers do not own the property that they farm. Another issue is that water is frequently unaffordable. Cities could address this by providing water at discount rates for urban farmers, with a requirement that they use efficient irrigation practices.

In the Bay Area and elsewhere, most obstacles to scaling up urban agriculture are political, not technical. In 2014 California enacted AB511, which set out mechanisms for cities to establish urban agriculture incentive zones, but did not address land access.

One solution would be for cities to make vacant and unused public land available for urban farming under low-fee multiyear leases. Or they could follow the example of Rosario, Argentina, where 1,800 residents practice horticulture on about 175 acres of land. Some of this land is private, but property owners receive tax breaks for making it available for agriculture.

In my view, the ideal strategy would be to pursue land reform similar to that practiced in Cuba, where the government provides 32 acres to each farmer, within a few miles around major cities to anyone interested in producing food. Between 10 and 20 percent of their harvest is donated to social service organizations such as schools, hospitals and senior centers.

Similarly, Bay Area urban farmers might be required to provide donate a share of their output to the region’s growing homeless population, and allowed to sell the rest. The government could help to establish a system that would enable gardeners to directly market their produce to the public.

Cities have limited ability to deal with food issues within their boundaries, and many problems associated with food systems require action at the national and international level. However, city governments, local universities and nongovernment organizations can do a lot to strengthen food systems, including creating agroecological training programs and policies for land and water access. The first step is increasing public awareness of how urban farming can benefit modern cities.

MIGUEL ALTIERI is a Professor of Agroecology at the University of California, Berkeley.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

A view of Aleppo from above. CC by 2.0

Aleppo: The Struggle to Rebuild a City After Years of War