150 years ago, Argentina’s African population was deliberately decimated. Today, the few Afro-Argentines remaining reckon with a trau

Read MoreFood Deserts, Food Swamps and Food Apartheid

Around 2.2 percent of all U.S. households live in areas without access to inexpensive healthy foods, leading to higher rates of obesity. These “food deserts” stem from a history of racism and inequality.

Food deserts are areas where residents don’t have easy access to healthy, affordable food. Instead, they may be overrun with fast food options. Mike Mozart. CC BY 2.0

Approximately 23.5 million Americans live in areas with limited or no access to affordable, healthy foods—especially fresh fruit and vegetables. These areas are commonly known as “food deserts” and are disproportionately found in low-income, minority communities.

Food deserts occur when there are few or no grocery stores within convenient distance; for example, a survey by the U.S. Department of Agriculture found that 2.3 million people live more than one mile away from a grocery store and do not have a car. In urban areas, the nearest grocery store might be a long trip away via public transportation, and not everyone is able to take time out of their day to make the trek, especially those in low-income neighborhoods who may be working more than one job.

Despite common misconceptions, living in a food desert does not necessarily mean that a person is food insecure. In fact, food deserts are often flooded with food choices—just not ones that are both healthy and affordable. A food desert may have plenty of smaller stores to buy food from, but these stores typically have limited options compared to grocery stores, specifically in the availability of fresh produce. Without easy access to grocery stores, people living in food deserts must turn to more convenient and affordable options, namely fast food.

Experts have coined the term “food swamp” to describe areas that are oversaturated with unhealthy food options. A study by the University of Connecticut’s Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity found that an average food swamp has four unhealthy eating options for every one healthy option.

Because people living in food deserts and food swamps have easier access to unhealthy food than healthy options, these areas also suffer from higher obesity rates. Studies have shown that food swamps may be a more accurate predictor of obesity rates than food deserts. However,food swamps and deserts tend to occur in the same areas, and more often than not these areas are low-income, minority communities.

The USDA has identified over 6,500 of what they refer to as “food desert tracts” based on census data and data about the locations of large grocery stores. In a 2012 study about the characteristics and causes of food deserts, the USDA found that areas with greater levels of poverty were more likely to be—or to become—food deserts. The study also concluded that “food desert tracts have a greater concentration of all minorities” than tracts that are not considered food deserts.

Because of the way that food deserts disproportionately impact minority communities, some food justice activists, like Karen Washington, prefer the term “food apartheid,” as it better captures the racial and economic nuances of the situation. Washington points out that “food desert” brings to mind “an empty, absolutely desolate place” with no food to be found, but this is not what a community with poor access to healthy food looks like. Nina Sevilla, another food justice activist, notes that “desert” implies that these areas are naturally occurring, which is not the case.

“Food deserts” are the result of decades of systemic racism that led to housing segregation; under the Federal Housing Administration starting in the 1930s, middle and lower-class white families migrated to the suburbs while minority families remained in urban housing projects. Redlining policies prevented minority groups from moving into what were seen as white neighborhoods. As white middle-class residents shifted to the suburbs, so did new supermarkets, leaving minority neighborhoods without easy access to a wide variety of food.

The term “food apartheid” highlights how these racist policies shaped low-income minority communities’ access to healthy food.

Since food inequality and so-called food deserts and food swamps are so rooted in racism, they are not an easy problem to address. However, there are many organizations working on different solutions to food apartheid, from championing policy reform to building alternative food systems, such as urban and small-scale farming and affordable organic grocery stores.

To Get Involved:

To learn more about where “food deserts” in the U.S. are located, look at the USDA’s Food Access Research Atlas here.

For a comprehensive policy platform on food, visit the HEAL Food Alliance here.

Rachel Lynch

Rachel is a student at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY currently taking a semester off. She plans to study Writing and Child Development. Rachel loves to travel and is inspired by the places she’s been and everywhere she wants to go. She hopes to educate people on social justice issues and the history and culture of travel destinations through her writing.

Remnants of Apartheid on South African Beaches

While apartheid has been dismantled in South Africa for more than 25 years, segregation is still visible on its seashores as the economic and social consequences of apartheid continue to disadvantage and discriminate against Black South Africans.

Read MoreBrazil’s Black Lives Matter Movement

Brazil, the last South American country to abolish slavery in the late 1800s, struggles to uplift their nation’s Black lives. Through pay gaps, urban designs, government representation and policing, Brazil’s society threatens the Black community.

A protester on the streets in Brazil. Michelle Guimarães.

Over the course of 300 years, approximately four million Africans were taken to Brazil as slaves. Today, Brazil’s racial demographics are 47.7 percent white, 43.1 percent multiracial and 7.6 percent Black. The average income for white Brazilians is almost double that of the average income for Black or multiracial Brazilians, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Also, 78.5 percent of people in Brazil who are receiving the lowest rate of income (equivalent to $5.50 U.S. dollars per day) are Black or multiracial people.

This May, Black Lives Matter protests filled the streets of Rio de Janeiro, Sao Paulo and Brasília after 28 people died during a police raid. Human rights activists said that the officers killed people who wanted to surrender and posed no threat. The raid took place in Rio de Janeiro, where heavily armed officers with helicopters and vehicles went into Jacarezinho, a poor neighborhood. Thousands of residents were subject to nine hours of terror.

Organizers said that 7,000 people took to the streets in Sao Paulo. Protesters painted the Brazilian flag with red paint and held up a school uniform stained with blood. In Rio de Janeiro, protestors chanted, “Don’t kill me, kill racism.”

As Brazilian author and activist Djamila Ribeiro said, “The Brazilian state didn't create any kind of public policy to integrate Black people in society," and that "although we didn't have a legal apartheid like the U.S. or South Africa, society is very segregated—institutionally and structurally."

In 2019, the police killed 6,357 people in Brazil, which is one of the highest rates of police killings in the world—and almost 80 percent of the victims were Black.

During COVID-19, Black Brazilians were more likely than other racial groups to report COVID-19 symptoms, and more likely to die in the hospital. Experts attributed this disparity to high rates of informal employment among Black people, preventing them from the ability to work from home, and a higher prevalence of pre-existing conditions. Specifically, in 2019, Black Brazilians already accounted for the majority of unemployed workers (64.2%); therefore, they already lacked economic support even before the pandemic.

An artist’s photoshoot with Brazil flag covering their bodies. Eriscolors.

Only a quarter of federal deputies in the lower chamber of Brazil’s Congress and a third of managerial roles in companies were Black people, according to the IBGE statistics from 2019.

Brazil’s President, Jair Bolsonaro, said during his campaign in 2018 that descendants of people who were enslaved were “good for nothing, not even to procreate,” while using the slogan “my color is Brazil.”

Keisha-Khan Y. Perry, a professor at the University of Texas, conducted an ethnographic study looking at how Black women in Gamboa de Baixo—a city culturally and historically tied to Black Brazilians—are leading the community towards social activism against racist politics. Specifically, these racist policies include political urban revitalization programs that push out Black and poor people. Perry said that these policies are a political tactic continually utilized in Brazilian cities.

However, recently in May, Milton Barbosa, one of the founders of the most notable Black civil rights organization in Brazil, Unified Black Movement, said, “There’s been an increase in awareness nationally… We still have to fight, but there have been important changes.”

Kyla Denisevich

Kyla is an upcoming senior at Boston University, and is majoring in Journalism with a minor in Anthropology. She writes articles for the Daily Free Press at BU and a local paper in Malden, Massachusetts called Urban Media Arts. Pursuing journalism is her passion, and she aims to highlight stories from people of all walks of life to encourage productive, educated conversation. In the future, Kyla hopes to create well researched multimedia stories which emphasize under-recognized narratives.

Anti-Asian Hate Spreads Across the Western World

In the past year, hate crimes against Asian Americans have risen 149%. But attacks are also growing around the world, here CATALYST reports on incidents in Spain (where 2.9% of citizens of Asian descent have experienced hate crimes), Scotland, Canada and Australia.

Read MoreSwiss Voters Support Burqa Ban Ahead of Nationwide Vote

A proposed referendum would ban full-face coverings in public spaces in Switzerland. Polls show that 63% of Swiss voters support the ban.

On March 7, Swiss citizens will vote on a referendum that would ban full-face coverings, like burqas and niqabs, from being worn in public. Polls show that 63% of Swiss voters support the ban and plan to vote in favor of it. The text of the ban, supported by members of Switzerland’s right-wing Swiss People’s Party, does not specifically mention Muslim veils, but the ban is widely seen as targetting face coverings worn by Muslim women.

The Swiss government has urged voters to reject the proposed ban, with officials saying that the decision to ban full-face coverings should be left up to individual cantons. Officials worry that a nationwide ban would “undermine the sovereignty of the cantons,” several of which have already banned such coverings in regional votes. In its statement, the government also noted that a ban on full-face coverings could harm Switzerland’s tourism industry. According to official statistics, only about 5% of the Swiss population is Muslim, and officials claim that the majority of women who wear facial coverings in Switzerland are visitors. For this reason, the Swiss government has deemed the burqa ban “unnecessary.” The government’s statement makes no mention of the potential for Islamophobia or anti-Muslim rhetoric to arise.

Despite the government’s lack of support for the burqa ban, the results of the referendum are directly in the hands of the Swiss people. Switzerland operates under a unique system of direct democracy. All Swiss citizens over the age of 18 have the right to vote in all elections and on all referendums. Citizens can also propose a referendum or an amendment to the constitution by getting 100,000 signatures of voters in support of the proposal within 18 months, a facet of direct democracy called a popular initiative. If the goal of 100,000 signatures is reached, the proposal will go to a nationwide popular vote. The proposal that would ban full-face coverings underwent this process and is now awaiting a vote.

The government cannot prevent a popular initiative from going to a vote, but it can offer a direct counterproposal in the hopes that a majority of the people and cantons will vote for it instead. In place of the burqa ban, the government has proposed a law that would require people wearing a facial covering to reveal their face for identification purposes at administrative offices or on public transport.

Those who refuse to remove their facial coverings would face fines of up to 10,000 Swiss francs ($11,200). If the proposed ban is rejected on March 7, the government’s counterproposal will go into effect.

Rachel Lynch

Rachel is a student at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY currently taking a semester off. She plans to study Writing and Child Development. Rachel loves to travel and is inspired by the places she’s been and everywhere she wants to go. She hopes to educate people on social justice issues and the history and culture of travel destinations through her writing.

‘Israel’s Most Racist Soccer Club’ Gets an Arab Owner

Fans are none too pleased. Beitar Jerusalem faces a tough fight against bigotry in its ranks.

A Beitar Jerusalem player, right, tries to keep up. Steindy. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Most sports fans would rejoice at such a deal. Beitar Jerusalem, an Israeli soccer team, got a new owner who pledged a $100 million investment in the team over the coming 10 years. Such a whopping sum of money could buy plenty of talent to buoy the team, which hasn’t won the Israeli Premier League since 2008. Instead of glee, though, many fans felt rage. One diehard spray-painted on the team’s stadium wall, “The war has just begun.” The reason was simple: the new owner was Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Nahyan, an Arab Muslim, and the team was Beitar Jerusalem, notoriously known as “the most racist team in Israel.”

Heckling Arab players is part and parcel of the stadium experience. Fans regularly shout “terrorist” at rival Arab players. The team remains ethnically homogeneous since it has never signed an Arab player. This flies in the face of statistical probability given that Israel’s population is 21% Arab. The team’s racial uniformity keeps with the team’s motto: “Forever Pure.”

A Beitar Jerusalem bumper sticker. zeeveez. CC BY 2.0.

To understand why Sheikh Hamad bought a 50% stake, it is necessary first to look at Moshe Hogeg, formerly the team’s sole owner. He made his fortune trading cryptocurrency and bought Beitar Jerusalem, along with its debt, for $7.2 million in 2018. His reasons were clear, ambitious and abrasive to many Beitar fans: “I saw this problem that reflects bad not only on the club, but also on Israel,” Hogeg said. “I love football, and I thought it was the opportunity to buy this club and to fix this racist problem. And then I could do something that is bigger than football.” Before he can even dream of something bigger, though, he’ll first have to address the bigotry already present in the team’s fan base.

Beitar Jerusalem’s self-avowed racist identity comes from a right-wing section of the fan base known as La Familia. Comprising roughly 20% of the team’s fans, they are a loud, vociferous and sometimes violent minority. When the team signed two Muslim players from Chechnya in 2013, members of La Familia burned down the team’s headquarters in retaliation. Fans routinely heckled the players during games. When one player scored his first goal, many fans, led by La Familia, left the stadium.

The tumultuous 2013 season was chronicled in the documentary “Forever Pure.”

Under pressure. Steindy. CC BY-SA 3.0.

The deal with Sheikh Hamad comes on the heels of the Abraham Accords, a set of agreements between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, brokered by the United States, that normalized relations between the two countries. Thousands of Israelis traveled to the UAE shortly after the agreements came into effect. Instagram influencers posted stories of themselves lounging in hotel suites in Dubai. Sheikh Hamad’s purchase of Beitar Jerusalem’s stake provoked very little attention in the UAE. Israeli football is not internationally popular, so the outcry was limited solely to Israel.

Beitar Jerusalem’s training ground, site of many racist chants. zeevveez. CC BY 2.0.

Sheikh Hamad is as hopeful as Moshe Hogeg about purging the team of its racist elements. “The deal is meant to show the nations that the Jewish and the Muslim can work together and be friends and live in peace and harmony,” Hamad said in December. However, peace and harmony still seem a long way away. Beitar Jerusalem’s decadeslong right-wing identity defines much of the team’s fan base. As embarrassed and ashamed as most fans are of La Familia’s overt bigotry, the group still holds immense sway. Only time will tell if their brand of hatred will win out. Hogeg and Sheikh Hamad’s anti-racism campaign will face fierce opposition. When asked if his decision to invest was related to La Familia, Sheikh Hamad only responded, “Challenge accepted.”

Michael McCarthy

Michael is an undergraduate student at Haverford College, dodging the pandemic by taking a gap year. He writes in a variety of genres, and his time in high school debate renders political writing an inevitable fascination. Writing at Catalyst and the Bi-Co News, a student-run newspaper, provides an outlet for this passion. In the future, he intends to keep writing in mediums both informative and creative.

London’s Mayor Promises Police Reform After Months of Unrest

In London, Mayor Sadiq Khan promises police reform after months of Black Lives Matter protests. By committing to hiring diverse police officers, Khan sets the precedent for other major cities to follow.

The Metropolitan Police Service at Trafalgar Square in London. CGP Grey. CC BY 2.0.

On Nov. 13, the mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, announced that by 2022, at least 40% of new recruits will be from minority backgrounds. Like many police forces around the world, London’s police have come under criticism in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests that began in the United States. London’s action in reforming its police force sets the precedent for other communities to follow.

The Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) is Britain’s largest police force. Also known as Scotland Yard and colloquially called the Met, MPS employs over 44,000 police officers and receives over 25% of the police budget for England and Wales. Along with most other police forces, the Met has come under criticism in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests and demands for police brutality reform. London’s record with police brutality is quite different than that of America’s, but it and racial inequality are still common across the United Kingdom. In the U.K., Black people are more than nine times more likely to be stopped and searched by the police than White people. Though people of color make up 13% of the population in England and Wales, 48% of minors in custody belong to the group.

While London is an incredibly diverse city, in 2017 an overwhelming 87% of MPS officers were White, with just 13.3% of officers identifying as Black and Minority Ethnic. These statistics have come under fire recently, with Black Lives Matter protesters taking to the streets of London demanding reform. Protesters turned out in thousands throughout the summer of 2020, with protest numbers spiking after Prime Minister Boris Johnson declared the U.K. as “not a racist country” and designating protesters’ behavior as “thuggery.”

Mayor of London Sadiq Khan. Steve Punter. CC BY 2.0.

Despite Prime Minister Johnson’s wavering views toward protests, the mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, acknowledged the institutional racism that he believes inflicts the country. In a statement from the mayor’s office, Khan said: “To the thousands of Londoners who protested peacefully today: I stand with you and I share your anger and your pain. George Floyd’s brutal killing must be a catalyst for change worldwide. No country, city, police service or institution can absolve itself of the responsibility to do better. We must stand together and root out racism wherever it is found. Black Lives Matter.” Khan’s acknowledgment of racism and discrimination is groundbreaking compared to American political leaders’ relative lack of action regarding this issue.

On Nov. 13, Sadiq Khan announced that by 2022, at least 40% of new recruits in the MPS will be from minority backgrounds. Metropolitan Police Commissioner Cressida Dick released a rare public statement acknowledging that the Met “is not free of discrimination, racism or bias.” Commissioner Dick also announced that her “job is to continue to try to eliminate any such racism and discrimination, however it appears.” London’s active anti-racist stance will set the precedent for other communities and cities to follow. This commitment to diversity is evidence of tangible and long-lasting change within potentially racist institutions.

Sarah Leidich

Sarah is currently an English and Film major at Barnard College of Columbia University. Sarah is inspired by global art in every form, and hopes to explore the intersection of activism, art, and storytelling through her writing.

How the BLM Movement Blossomed in the UK

As voices of the Black Lives Matter movement flooded American streets, British proponents alike rushed to rally. The seeds of the movement germinated in the U.K., but problems soon sprung up alongside them.

Black Lives Matter protest in Bristol, England. KSAG Photography. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

In late May, the death of George Floyd ignited outrage in nations across the world, including in the United Kingdom. In the early summer months, the pages of social media and eager British ralliers mirrored the zeal of the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States. However, over the course of a few short months, the unmatched vigor of the movement in Britain quickly dropped off; neither the media channels nor the once fiery minds of residents continued active coverage and support.

What had started as weekly protests in Britain’s largest cities had dissolved into a deferred dream for a few young activists. As more racial inequalities surfaced, less and less government engagement was found.

Regardless of this obstacle, the young remaining supporters continue their fight with the unbattered zeal of seasoned activists. A few such activists are the founders of All Black Lives U.K., which is a movement started this past May by a group of students. The group organized protests for 10 weeks this summer and has since made substantial headway; its outreach, primarily made through social media and hosted panels, has garnered enough engagement to establish posts in other urban areas such as Bristol and Manchester.

The movement pushes for a list of demands to be met by the government, which includes the removal of the highly scrutinized “gangs matrix.”

The gangs matrix is a database that has been run by the Metropolitan Police since 2012 following the 2011 London riots. The database contains the names of “gang nominals,” or people whose online activity has been flagged for suspected gang affiliation. The Metropolitan Police advertised the database as a tool to combat violence in London, but many studies found that its standards have resulted in the disproportionate representation of young Black males. Thus, All Black Lives U.K. believes that the abolition of this database will remove a racist stronghold in the government.

Aside from more obvious racial discrimination, many protesters think that the U.K. suffers from a profound lack of diversity. The movement continues to fight for increased inclusion of Black voices in local councils, as well as diversity in the national school curriculum. Campaigns have been launched to modify what is included in the national curriculum, specifically in order to make learning Black history compulsory. Proponents intend for this modification to fairly represent the Black population while creating a more well-rounded picture of the nation’s history for all students. The education campaigns were met with immediate backlash, with claims by educators that this change is too closely tied to political extremism.

With several months of tumult having reshaped the face of racial discussions in the U.K., there is little that the British government has changed to address the issue. However, the few brave faces trailblazing the movement keep pressing on, calling others to educate themselves in the meantime.

To Get Involved

To sign up to volunteer for the Black Lives Matter movement in the UK, click here.

To find out more about the Black Lives Matter movement in the UK, click here.

To become a partner or sponsor for the movement in the UK, click here.

Ella Nguyen

Ella is an undergraduate student at Vassar College pursuing a degree in Hispanic Studies. She wants to assist in the field of immigration law and hopes to utilize Spanish in her future projects. In her free time she enjoys cooking, writing poetry, and learning about cosmetics.

Indonesian Muslims Protest French President

Thousands of people gathered at Indonesia’s French Embassy to protest French President Emmanuel Macron. Macron has a history of anti-Muslim rhetoric and recently defended the publication of caricatures depicting the Prophet Muhammad.

On Nov. 2, thousands of people gathered outside the French Embassy in Jakarta, Indonesia, to protest French President Emmanuel Macron.

Macron defended the publication of cartoons that depict the Prophet Muhammad, which many have deemed inflammatory. The cartoons were originally published in the Charlie Hebdo magazine in 2015. They were republished in September to mark the opening of the trial for the 2015 attacks against the magazine’s staff, which were partially motivated by the publication of the cartoons.

Last month, the cartoons were a topic of discussion in a Paris classroom during a lecture on freedom of expression. After the lecture, on Oct. 16, the teacher who led the class was beheaded by a student enraged by the cartoon being shown in class. In a separate incident on Oct. 29, three people were stabbed to death in the seaside town of Nice by a Tunisian man yelling “Allahu Akbar,” a commonly used phrase meaning “God is greatest.” Though it has an innocuous meaning and is used in a number of day-to-day situations, the phrase has been tarnished by an association with terrorist acts, such as the 2015 Charlie Hebdo attack.

These recent incidents have reinvigorated anti-Muslim sentiment in France, and Macron has been criticized for his comments. Macron told the news site Al-Jazeera that he understands people’s concern over the cartoons, but said that he “will always defend in my country the freedom to speak, to write, to think, to draw.” He maintained his stance that the cartoons were protected under freedom of expression after the beheading of the teacher in October, and has been accused by some of spreading anti-Muslim sentiment in his statements.

Macron has received criticism for his anti-Muslim rhetoric in the past. On Oct. 2, he called Islam a religion “in crisis” around the world and introduced a plan to push what he termed “Islamist radicalism” out of French education and the public sector. In the same speech, he announced the government’s intention to present a bill strengthening a 1905 law officially separating the church and state in France.

In Indonesia, the French Embassy was heavily guarded and protected by barbed wire, but over 2,000 people stood outside chanting and holding signs. Protesters displayed banners that read “Macron is the real terrorist,” “Go to hell Macron,” and “Macron is devil” and called for a boycott of French goods. Some protesters stomped on Louis Vuitton bags to demonstrate their rejection of French products. Speakers at the protest demanded that Macron apologize and take back his anti-Muslim comments. They also called for the immediate removal of the French ambassador.

On Oct. 31, Indonesian President Joko Widodo condemned the terrorist attacks in Paris and Nice while also speaking out against Macron’s defense of the cartoons. Widodo argued that freedom of expression that tarnishes the honor of religious symbols could not be justified and said that “linking religion with terrorist acts is a big mistake.” Muslims in France have repeatedly denounced the terrorist acts.

Rachel Lynch

is a student at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY currently taking a semester off. She plans to study Writing and Child Development. Rachel loves to travel and is inspired by the places she’s been and everywhere she wants to go. She hopes to educate people on social justice issues and the history and culture of travel destinations through her writing.

OPINION: Technology Brings Light to Social Issues—But Can It Implement Lasting Change?

The Black Lives Matter movement in the United States sparked global protests and conversations about the treatment of typically “othered” groups. Despite pressure on social media, education and effective policy reform are still needed to achieve justice for all.

A Black Lives Matter protest sign in London. Ehimetalor Akhere Unuabona. Unsplash.

Following the deaths of Black Americans like George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor, Black Lives Matter surged into the spotlight with renewed vigor. Nationwide protests against police brutality and systemic racism revived conversations about the importance of diversity, equity and inclusion in public spaces. To avoid the consequences of “cancel culture”—the boycott of businesses that fail to embrace social change—many organizations reaffirmed their commitment to racial justice.

On its Twitter account, Netflix emphasized “speaking up” and standing with Black Lives Matter. The ice cream chain Ben and Jerry’s posted “We Must Dismantle White Supremacy” on its website. Some brands even reinvented themselves. Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben’s came under fire for reinforcing backwards racial stereotypes of Black individuals. Their respective parent companies, Quaker Oats and Mars Inc., acknowledged the problematic history of these marketing depictions and committed to changing them.

While many have lauded these actions, others remain skeptical. “Woke washing,” as defined by diversity and inclusion expert Marlette Jackson, is when companies make “public commitments to equality” but fail to create the infrastructure that actually supports Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) staff. For example, Bon Appetit, a monthly American magazine dedicated to global cuisines and recipes, was outed for its empty promises of change. Priya Krishna, a former Test Kitchen star, revealed on Twitter that she was not fairly compensated for her work. She added that staff of color were “tokenized” and framed as “monolithic experts for their communities.” Krishna has since left Bon Appetit.

A billboard for the skin whitening company Fair & Lovely in Bangladesh. Adam Jones. CC BY-SA 2.0

Despite instances of smoke screen marketing, Black Lives Matter has sparked questions of colorism and colonial legacies in countries like India.

In India, lighter skin is considered more desirable. This age-old belief has created a lucrative market for skin whitening products. Not only does the existence of this industry foster a culture of body insecurities, but the products themselves also contain dangerously high levels of mercury and hydroquinone. Since the rise of Black Lives Matter protests in June, many Indian celebrities like Priyanka Chopra have condemned racial injustice in the United States. However, Chopra herself filmed an ad with Fair & Lovely, one such skin lightening product.

According to activist Kavitha Emmanuel, many Indians are “blind to colorism, caste discrimination and violence against religious minorities at home.” Muslims have been lynched in increasing numbers since the ascension of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his party’s Hindu nationalist government. However, many feel that Indians have been more critical of American injustices than the ones happening in their own country. Ultimately, the question remains: are conversations alone enough to achieve lasting peace?

Despite posthumously gracing the cover of Vanity Fair, despite hashtag trends, and despite over 11 million petition signatures as of Oct. 2, Breonna Taylor did not find justice. While the instant and global nature of the internet cultivated efforts to educate and reform, these gestures will not be enough. Unless individuals reexamine the internalized racism and national narratives that so often rule their reactions, ostracized populations will find no reprieve. Until governments step in with effective laws and limitations—ones free of loopholes—Black and marginalized individuals across the globe will continually be devalued and delegitimized.

Rhiannon Koh

earned her B.A. in Urban Studies & Planning from UC San Diego. Her honors thesis was a speculative fiction piece exploring the aspects of surveillance technology, climate change, and the future of urbanized humanity. She is committed to expanding the stories we tell.

Is the South African Apartheid Actually Over?

The economic disparity in South African metropolises like Johannesburg points back to the apartheid, with one side of town obviously White and upper-middle class while the other is mostly Black and full of rundown, tottering homes.

Kuku Town, a small settlement of Black South Africans on the outskirts of Cape Town. Slum Dwellers International. CC BY 2.0.

The South African apartheid officially ended in 1994, abolishing the country’s long-standing policy of racial segregation across its social and economic relations. 26 years later, though, remnants of the apartheid are still apparent in the infrastructure of South Africa’s largest cities. As it stands, a majority of the country remains segregated as a result of systemic racism.

South African cities Johannesburg, East Rand and East London have the greatest income inequality in the world; multimillionaires flock to luxurious homes in close proximity to overpopulated and underserved townships. It is clear that the dissolution of the apartheid state, although significant, represented more of a symbolic change than a material one. The notable rise of a Black middle class fails to overshadow the fact that almost two-thirds of South Africa’s Black population lives below the poverty line.

Johannesburg’s central business district, which was largely abandoned by top firms in favor of the city’s affluent suburbs. Evan Bench. CC BY 2.0.

A Brief History of the Apartheid

Beginning in 1948, the South African government attempted to shift its economic and political conditions through stringent racial segregation. Spearheaded by the White supremacist National Party, the apartheid separated South Africa into four “nations”: Black Africans, “Coloureds” (those of mixed ancestry), Asians and Whites. . Whites received preferential treatment in nearly every aspect of society, with Black Africans facing the most severe discrimination.

These enforcements impacted public spaces, but also regulated marital practices and sexual relations. Black and White people were banned from participating in romantic relationships with each other. One of the most visible actualizations of segregation, though, occurred decades before the apartheid began through a series of “Land Acts.” These discriminatory laws, passed in 1913, granted 86.5% of South Africa’s property to Whites and restricted nonwhite individuals from entering these sectors without proper documentation.

Over the decades of apartheid, there existed a constant threat of violence against nonwhite individuals by the government. Rural regions newly designated as “Whites-only” led to Black South Africans being violently removed from their homes and displaced into remote and abjectly poor regions called “Bantustans.” From 1961 to 1994, up to 3.5 million Black people were forcibly removed from their homes. The state-sanctioned violence ended in the mid-1990s with the enfranchisement of nonwhite groups and the integration of all races. The decades of government-enforced violations of basic rights, however, have solidified the material and political disadvantages of South Africa’s Black majority.

Glimpses of the Apartheid Today

The integration which occurred in 1994 proved to be ineffectual; the historically White neighborhoods remain the same while the districts for Black people are also still homogenous. These predominantly Black neighborhoods often suffer from high crime rates and debilitating unemployment rates. The legislation regarding South African race relations may have changed, but socioeconomically, Blacks are disproportionately unemployed and paid less when in the labor market. Johannesburg’s predominantly-White suburbs of Sandton and Sandhurst taunt the majority with $10 million homes, attracting the richest 20% of the country who hold 68% of all wealth.

A South African citizen, Ntandoyenkosi Mlambo, shared her sentiments with The Guardian about the current state of Cape Town: “The constitutional right to movement has changed so people of color are able to move in different areas. However, the economic and land ownership disadvantages which are still linked to people of color make cities inaccessible for most to live and thrive in. Also, the criminalization of homelessness further entrenches the lived reality that only a few have the right to the city.”

The lifting of the apartheid did significantly increase the size of the Black middle class and allowed some to attain wealth. However, the diversification of the suburbs can hardly be considered progress when the top 10% of Black South Africans own nearly 50% of the group’s income. The state provided grants to members of the lower class in an attempt to decrease income inequality, but the policy has so far fallen short of substantial change.

Heather Lim

recently earned her B.A. in Literatures in English from University of California, San Diego. She was editor of the Arts and Culture section of The Triton, a student-run newspaper. She plans on working in art criticism, which combines her love of visual art with her passion for journalism.

People at a market in Georgetown, Guyana, before the COVID-19 pandemic. M M from Switzerland. CC BY-SA.

Tensions Soar Following Racially Motivated Murders of Three Guyanese Teenagers

Following a hotly contested election, the murders of three Guyanese teenagers have sparked renewed racial tensions in Guyana between the country’s two main ethnic groups, Afro-Guyanese and Indo-Guyanese. This comes as the world is having a broader conversation on racial justice, which was sparked by the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement in May.

The bodies of Afro-Guyanese teenagers Isaiah and Joel Henry were found mutilated in coconut fields in the Mahaica-Berbice region on Sept. 6. Haresh Singh, an Indo-Guyanese teenager, was killed three days later while trying to pass through a protest that had started in response to the initial murders.

“I will work day and night to get to the bottom of what happened to those teens,” President Irfaan Ali said in a press release. “Safety and security in all of the communities remain a top priority. As you can see, there is more visibility on the ground, more resources on the ground … We cannot tolerate lawlessness and criminality. We have to fix what went wrong and move forward.”

Volda Lawrence, chairperson of the political party People’s National Congress Reform, released a statement condemning the racist murders and stating that racism cannot be combated with more racism.

“My brothers and sisters, our protest must not end until justice is served,” Lawrence said. “I am resolute in my stance to go the full mile with you, until we achieve our desired outcome, justice. But we must protest in a peaceful and civil manner, doing so with respect for human life, dignity and property. Our protest must be solution-oriented and not driven by chaos, violence and destruction. For those that have utilized violence or caused destruction, please refrain from such acts as we seek justice for those who were taken from us.”

In response to the three racially motivated murders, the Guyana Human Rights Association plans to submit a formal request for the United Nations to investigate the killings with forensic pathology.

“This call is not intended to cast doubt on the capacity or impartiality of local investigators, so much as a response to the deep distrust accompanying the political polarization of the society,” the organization said in a statement on Sept. 8. “These callous murders are not seen as isolated. Both sides are quick to see them as a continuation of earlier ethnic upheavals … Both sides feel accumulated bitterness towards a system that has accommodated such turmoil.”

The protests surrounding the murders parallel those around the world in support of racial equality. Hundreds of thousands of people globally have continued to protest in support of the Black Lives Matter movement following the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery earlier this year. This has since inspired activists to broaden the movement, highlighting other instances of racial injustice in their own communities including police brutality against Indigenous Australians.

What differs in the case of Guyana is that while racism has been an issue in the country since its inception, tensions have increased following massive oil discoveries and the election of President Ali in March.

The discovery of oil off the coast of Guyana has set the country on course to expand its economy by 50% by the end of 2020, which would give it the fastest-growing economy in the world in a time when a global recession looms due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

The presidential race, which was between then-incumbent David Granger, who was backed by Afro-Guyanese supporters, and Ali, who is now South America’s first Muslim head of state and was backed by Indo-Guyanese supporters, centered around racializing the oil discoveries by both candidates claiming that their supporters would lose out on profits if the other candidate was elected.

Deodat Persaud, a member of Guyana’s Ethnic Relations Committee, told The New York Times that “racism is connected to political power in Guyana.”

In the week that has followed since the initial murders, President Ali has visited with the families of all three slain teenagers and has ordered the government to begin enforcing the Racial Hostility Act and the Cybercrime Act in an effort to crack down on virtual hate speech.

Jacob Sutherland

Jacob is a recent graduate from the University of California San Diego where he majored in Political Science and minored in Spanish Language Studies. He previously served as the News Editor for The UCSD Guardian, and hopes to shed light on social justice issues in his work.

Locked Up: Unmasking Australia’s Aboriginal Youth Prison Crisis

The Aboriginal people have been severely marginalized by Australia’s government, but among the most impacted are the group’s children.

A young Aboriginal girl. mingzhuxia. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Indigenous people make up approximately 3% of Australia’s overall population and are considered the country’s most disadvantaged group. It is believed that the Aboriginal people lived in Australia for over 47,000 years prior to European colonization. Even today, the Aboriginal people continue to suffer some of the consequences of violent colonization such as low literacy rates, low life expectancy and a high unemployment rate.

Aboriginal children in particular are 30 times more likely to be stopped and prosecuted than other Australian youths. This reveals a pattern of racial profiling and stereotyping that has been called out by protests affiliating with the U.S.’s Black Lives Matter movement.

Progress was made in 2018, when police in Western Australia apologized for practicing “forceful removal,” the separation of Indigenous children from their families. Forceful removal was popular throughout the late 19th century and was legal until 1969. Many refer to those impacted by forceful removal as the “Stolen Generation.”

Since May 26, 1998, Australians have observed “National Sorry Day” as a way to apologize to the Aboriginal people for the harmful practice. It is a nationwide campaign committed to paying homage to affected groups while teaching youth of Australia’s harmful past actions. In 2008, former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made a proposal in front of Parliament to help bridge the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

Australia’s National Sorry Day in 2015. butupa. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Yet, the gap between the Aboriginal community and other Australians remains as wide as ever. In February, the police of New South Wales revealed details about the Suspect Targeting Management Plan, which is intended to prevent future crimes by targeting likely or repeat offenders. Reports from 2016 to 2018 show that up to 72% of targeted children were likely from Indigenous descent. The youngest child identified was 9 years old.

The minimum age of criminal responsibility in Australia is one of the lowest in the world, allowing children as young as 10 to be sentenced to jail. Additionally, Aboriginal children are 17 times more likely to be jailed than non-Indigenous youth. Statistics from Western Australia say that 60 to 70% of children currently being held in the state’s detention centers are of an Aboriginal background.

As of now, very little research proves that locking up children reduces criminal activity in the future. In fact, youth already in the criminal justice system are far more likely to be repeat offenders, challenging the original intent of New South Wales’ Suspect Target Management Plan.

There is a push by lawyers and advocacy groups to raise the age of criminal responsibility in Australia to at least 14. Others believe that an alternative is to provide better health care and other social services in an attempt to elevate Aboriginal children’s socioeconomic standing. The end goal would be to improve their overall quality of life, allowing for better employment opportunities and an end to the societal obstacles currently facing the group.

Eva Ashbaugh

Eva is a Political Science and Gender, Sexuality, and Women's Studies double major at the University of Pittsburgh. As a political science major concentrating on International Relations, she is passionate about human rights, foreign policy, and fighting for equality. She hopes to one day travel and help educate people to make the world a better place.

The Back-to-Africa Movement: A Response to Racism

Some Black Americans have chosen to move to Africa to embrace their heritage and ancestral roots after experiencing racism, violence and stereotyping in the United States.

A village in Tanzania. ceasrgp. CC BY-SA 2.0

The Back-to-Africa movement was initially started to encourage those of African ancestry to travel back to Africa where their ancestors once lived. Even though many are unsure of the movement’s founder, many in the U.S. attribute it to Marcus Garvey, who founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association in 1914 in New York City’s Harlem district. He encouraged many Black people to seek social equality even if it meant moving to Africa through “self-emancipation.”

However, the Back-to-Africa movement can be traced even further back to the 19th century and the establishment of the American Colonization Society The predominantly-White group, founded by Robert Finley in 1817, shipped up to 12,000 freed slaves and freeborn Black Americans to Liberia. Historians’ views on the American Colonization Society’s work remain split; some view it as an early group dedicated to Black Americans’ freedom while others see it as nothing more than an attempt to remove Black people from the United States. Either way, the group was unpopular among the African American community, and should not be confused with more recent Back-to-Africa movements.

Painting of Marcus Garvey. David Drissel. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Many African Americans have more recently picked up the Back-to-Africa movement to help strengthen Black identity. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcom X both made visits to Ghana in order to reconnect with their heritage.

Obadele Kambon is a recent example of the modern Back-to-Africa movement. Kambon was living in Chicago in 2007 when he was wrongfully accused of possessing a loaded firearm illegally in his car. In reality, he had an unloaded, licensed gun. The fear of mistreatment and wrongful convictions, sometimes even leading to death, was a main influence in Kambon’s decision to move to Ghana in 2008.He said his participation in the Back-to-Africa movement made him realize what it “feels like to be a White person in America, just to be able to live without worrying that something is going to happen to you.”

Many of those who have moved to Africa from the United States fear that “nothing can fix [racism].” Africa holds the potential to reconnect people with their roots while offering them a life less affected by racism and violence. 71% of African Americans in the United States have said that they have experienced discrimination in some form. For many African Americans, heading abroad frees them from the need to prove themselves to be more than their skin color.

2019 was marked by Ghanaian President Nana Akufo-Addo as the “Year of Return.” It coincided with the 400th anniversary of what is believed to be the first enslaved Africans arriving in the United States. Last year, Ghana rewarded over 100 citizenships to Black individuals from the Americas as a part of its “Year of Return” initiative. The campaign brought over 500,000 visitors to the region—and some of them have decided to stay.

Eva Ashbaugh

is a Political Science and Gender, Sexuality, and Women's Studies double major at the University of Pittsburgh. As a political science major concentrating on International Relations, she is passionate about human rights, foreign policy, and fighting for equality. She hopes to one day travel and help educate people to make the world a better place.

Harajuku, Japan. SkandyQC. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Why Fertility Rates Could Halve by 2100

The global population growth rate is predicted to take a drastic downward turn, with experts believing that major countries such as Japan and Italy will see their populations halve by 2100. This is an unprecedented problem that could negatively impact society as a whole if the trend continues. The necessity for the world to plan and prepare for this outcome has become increasingly clear as global trends solidify.

Why the Sudden ‘Baby Bust’?

In the 1950s, women were having an average of about 4.7 children in their life span. In today’s world, women are instead averaging 2.4. The causes for this turnaround include increased educational opportunities, greater numbers of women in the workforce and increased access to contraceptives. There seems to have been an attitude change toward parenthood in recent years. In more developed countries, the roles of women have turned in favor of being outside the home, leaving less time for children. This contrasts starkly with historical norms, where women stayed home to take care of the family and house while men left to go to work.

What Are the Global Consequences?

While an initial evaluation might suggest that a smaller population would be better for the environment, professor Christopher Murray of the University of Washington suggests that this would lead to an “inverted social structure” where there are more older people than young. This raises questions about who will pay taxes and take care of the elderly. These are issues that the younger generations will have to worry about as they reach adulthood. “We’ll have to reorganize societies,” Murray says, in order to make current population trends sustainable.

The world’s changing population numbers could lead to a shift in the world’s dominant powers. For example, India is set to replace China as the world’s most populous country as China faces a population decline as soon as 2024. By 2100, India’s population would be followed by Nigeria’s, China’s and the United States’.

Why Nigeria?

As COVID-19 and other health challenges ravage developing countries, access to contraceptives and other family planning becomes limited. This leads to more pregnancies in places such as sub-Saharan Africa, which is set to “treble in size.” Africa’s forecast for rapid growth calls attention to the current social situation regarding racism, with Murray stating that “global recognition of the challenges around racism are going to be all the more critical if there are large numbers of people of African descent in many countries.”

This shift in global power is expected to create issues surrounding development, social status and racism. Especially in the current social environment, racism could become one of the largest issues if these predictions prove to be true.

What is Being Done to Prevent Population Decline?

Countries such as the United Kingdom have incentivized and increased migration. However, this is only a temporary fix as most countries begin to drop in population. Other countries have increased paid maternity and paternity leave, but have still seen few shifts toward larger families. Sweden has managed to “drag its rate from 1.7 to 1.9” while Singapore still has a rate of 1.3. Women simply cannot be expected to increase the number of children they have due to policy changes, and current trends show that this attempt will not be enough.

If the global reproductive rate drops to the predicted 1.7 by 2100, population extinction could become more of a legitimate concern. The 2.1 threshold, which is necessary to sustain the world’s current population, is instead being used as a target for future growth. Ultimately, though, young adults need to start planning for a future where society’s age makeup is inverted.

Elizabeth Misnick

is a Professional Writing and Rhetoric major at Baylor University. She grew up in a military family and lived in Europe for almost half her life, traveling and living in different countries. She hopes to continue writing professionally throughout her career and publish her writing in the future.

Athletes Want an End to the Protest Ban at the Olympics

Raised Black fist. Oladimeji Odunsi. Unsplash

Olympic athletes are urging the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to remove a rule that seems out of place to some as protests sweep every corner of the world. Currently, the Olympic Charter stipulates in Rule 50 that, “No kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas.” Various institutions have reckoned with similar issues in recent months, and the IOC and the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee are the latest to be criticized for their rules forbidding displays of political protest.

Various athletic organizations, athletes and some sports administrators have spearheaded the movement and joined in solidarity with the push to create meaningful change for the rights of athletes. Global Athlete, an athlete-led group, said in a statement, “Athletes have had to choose between competing in silence and standing up for what’s right for far too long. It is time for change. Every athlete must be empowered to use their platforms, gestures and voice. Silencing the athlete voice has led to oppression, silence has led to abuse, and silence has led to discrimination in sport.”

This statement reflects the historic moments of protests at Olympic events, including when at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised their fists on the medal stand. They were immediately sent home. Furthermore, this year the IOC doubled down on its rules against political protest after track athlete Gwen Berry raised her fist on the medal stand and fencer Race Imboden took a knee at the 2019 Pan American Games. It is only this month, after mounting pressure, that “IOC President Thomas Bach said the athlete group would “explore different ways” opinions could be expressed during the games — while still “respecting the Olympic spirit.”

A new athlete-led group was established on July 16 by Olympian Christian Taylor called Athletics Association “to stand up for athletes who have long felt underrepresented at the sport’s top table.” According to Taylor, the Athletics Association’s short-term goal is to see Rule 50 gone, but it also has many long-term goals for the welfare of athletes facing many Olympic committees that have not done their part. These goals, according to The Independent, include starting a “hardship fund” for athletes struggling to make ends meet, education programs on financial literacy “to help athletes not leave the sport broke,” reversing World Athletics’ controversial plans to strip down the Diamond League and ultimately driving a power shift from governing bodies to athletes.

To follow suit, Brian Lewis of the Caribbean Association of National Olympic Committees agreed with the notion that “arguing the oft-cited IOC notion that sports should be free of politics is not realistic.” As Gwen Berry put it, many Olympians believe that, “Rule 50 needs to be canceled for the simple reason that it goes against athletes’ human rights. There are rights inherent to all human beings and one is the freedom of speech.”

Hanna Ditinsky

is a sophomore at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and is majoring in English and minoring in Economics. She was born and raised in New York City and is passionate about human rights and the future of progressivism.

10 Places to Honor Black History and Culture

Through artwork, literature, music and history, these institutions amplify Black voices and address race relations in America.

George Floyd protests in Charlotte, North Carolina. Clay Banks. Unsplash.

Amid global protests against racial injustice, a growing number of people are educating themselves on systemic racism and white privilege.

1. Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park - Atlanta, Georgia

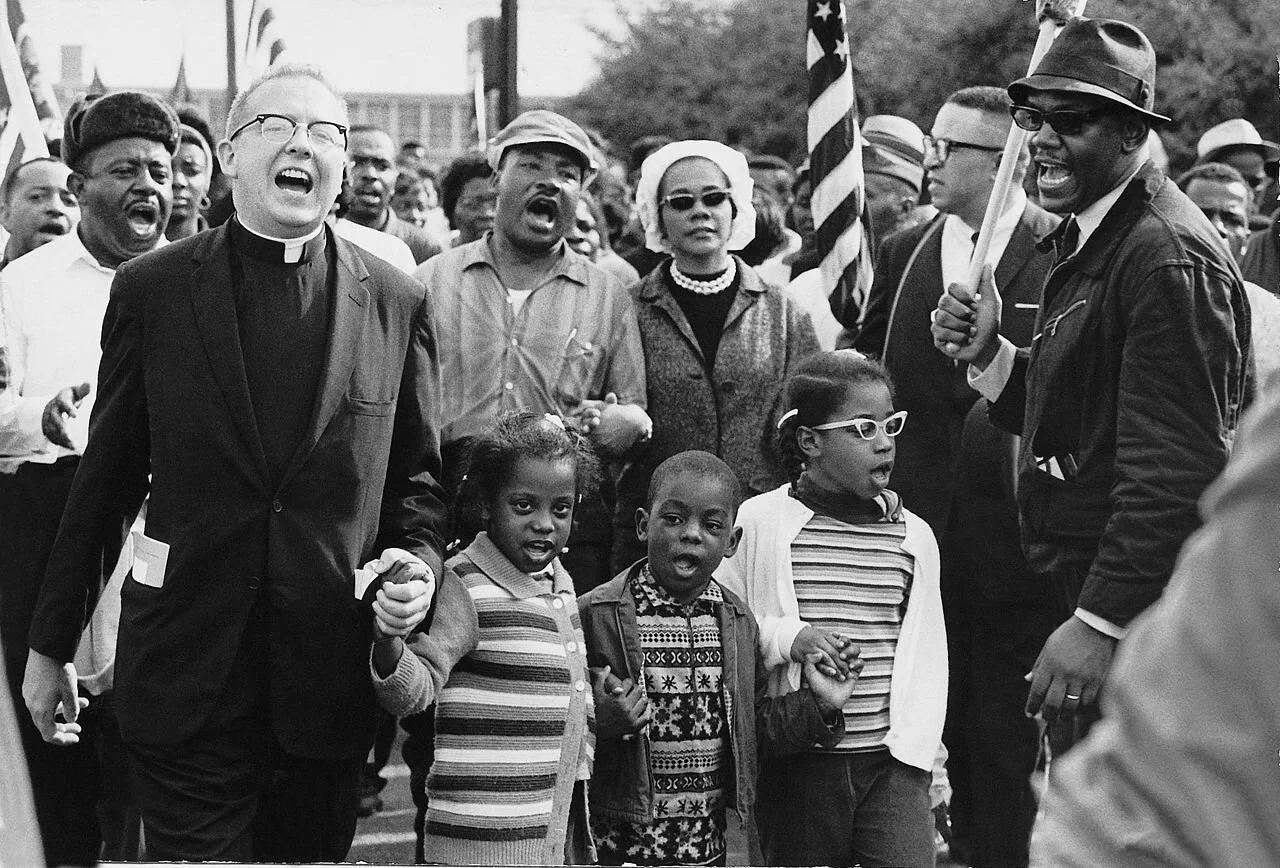

Martin Luther King Jr. locating civil rights protests. Thomas Hawk. CC BY-NC 2.0

Located in one of Atlanta’s historic districts, the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park honors the activist who strove for racial equality. The site includes a museum chronicling the American civil rights movement, as well as Dr. King’s childhood home, garden and gravesite. With 185 varieties of roses, the “I Have a Dream” World Peace Rose Garden promotes peace between diverse world communities. Each year, students from the greater Atlanta area write poems that express the ideals of MLK, such as using civil disobedience to reach seemingly impossible goals. These “Inspirational Messages of Peace” are exhibited among the flowers and are read by thousands of visitors each year. Directly across the street is the final resting place of Dr. King and Coretta Scott King, his wife, surrounded by a reflection pool.

Until his assassination in 1968, King preached at Ebenezer Baptist Church, known as “America’s Freedom Church.” The church has continued to serve the Atlanta community since his death, vowing to “feed the poor, liberate the oppressed, welcome the stranger, clothe the naked and visit those who are sick or imprisoned.” While sitting in the pews, visitors hear prerecorded sermons and speeches from Martin Luther King Jr. Most recently, the funeral of Rayshard Brooks, a Black man fatally shot by police, was held at the church, with hundreds of prominent pastors, elected officials and activists in attendance.

2. National Museum of African American History and Culture - Washington, D.C.

A student at the NMAAHC uses an interactive learning tool. U.S. Department of Education. CC BY 2.0

The National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) is the only museum devoted exclusively to African American life, history and culture. In the words of Lonnie Bunch III, founding director of the NMAAHC, “The African American experience is the lens through which we understand what it is to be an American.” From slavery to the civil rights movement, the museum aims to preserve and document Black experiences in America. With the launch of the Many Lenses initiative, students will gain a greater understanding of African American history by studying museum artifacts and discussing cultural perspectives alongside scholars, curators and community educators. Through the Talking About Race program, the museum provides tools and guidance to empower people of color and inspire conversations about racial injustice.

3. Black Writers Museum - Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Langston Hughes, a famous writer featured at the BWM, signs autographs. Washington Area Spark. CC BY-NC 2.0

Built in 1803, the historic Vernon House includes the Black Writers Museum (BWM), the first museum in the country to exhibit classic and contemporary Black literature. The BWM celebrates Black authors, like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, who documented the resilience and resistance of African Americans throughout history. Supreme D. Dow, founder and executive director of the Black Writers Museum, noted, “There was a time in American history when Black people were denied the human right to read or write. But, because of the innate drive to satisfy the unquenchable thirst for self determination, our ancestors taught themselves how to read and write in righteous defiance of the law, and in the face of fatal repercussions.” Through books, newspapers, journals and magazines, the museum honors the Black narrators of history. The BWM also strives to inspire future African American authors with community activities like poetry readings, cultural arts festivals and book signings.

4. Tubman Museum - Macon, Georgia

Artwork depicting Harriet Tubman on the Underground Railroad. UGArdener. CC BY-NC 2.0

Named after Harriet Tubman, the “Black Moses” who led hundreds of slaves to freedom, the Tubman Museum has become a key educational and cultural center for the entire American Southeast. Through artwork and artifacts, the main exhibits recount the struggles and triumphs of Tubman, a former slave, abolitionist and spy. The “From the Minds of African Americans” Gallery displays inventions from Black inventors, scientists and entrepreneurs, such as Madam C.J. Walker and George Washington Carver. The Tubman Museum also actively contributes to the Macon, Georgia, community. The Arts & History Outreach program takes Black history beyond museum walls. Local African American artists and teachers bring museum resources into the classroom, promoting hands-on learning. Due to COVID-19, the museum recently launched a distance learning program to provide people at home with a deeper understanding of the African American experience.

5. Museum of the African Diaspora - San Francisco, California

Contemporary art by Kehinde Wiley exhibited at the MoAD. Garret Ziegler. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD), a contemporary art museum, celebrates Black culture from the perspective of African diaspora. Focused exclusively on African migration throughout history, the museum presents artwork, photography and artifacts related to the themes of origin, movement, adaptation and transformation. Currently, MoAD is featuring various exhibitions from emerging artists that explore ancestral memory and Black visibility. As active members of the San Francisco community, museum curators offer various programs like public film screenings, artist talks and musical performances. In response to worldwide protests, the museum created a guide with resources to support Black Americans, as well as a video series that promotes community resilience. Monetta White, MoAD’s executive director, announced, “Now more than ever, we affirm that Museums are Not Neutral. As humanitarian educators and forums for conversation, museums are a space to confront some of the most uncomfortable conversations in human history.”

6. National Museum of African American Music - Nashville, Tennessee

Jimi Hendrix, a featured musician at the NMAAM. Clausule. Public Domain.

Scheduled to open its doors for the first time on Sept. 5, the National Museum of African American Music (NMAAM) will be the first museum in the world to showcase African American influence on various genres of music, such as classical, country, jazz and hip-hop. NMAAM will integrate history and interactive technology to share music through the lens of Black Americans. “African American music has long been a reflection of American culture. Additionally, African American musicians often used their art as a ‘safe’ way to express the way they felt about the turbulent times our country faced,” said Kim Johnson, director of programs at the museum. NMAAM will also support the Nashville community through various outreach programs. From Nothing to Something explores the music that early African Americans created using tools like spoons, banjos, cigar box guitars and washtub basins. Children receive their own instruments, learning how simple resources influenced future music genres. Another program, Music Legends and Heroes, promotes leadership, teamwork and creativity in young adults. Students work together to produce a musical showcase in honor of Black musicians. In 2015, student guitarists paid tribute to Jimi Hendrix, the rock icon. “This opportunity gave them a real-life connection to an artist they had only seen in their textbooks or online,” said Hope Hall, librarian at the Nashville School of the Arts.

7. The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration - Montgomery, Alabama

Exterior of the Legacy Museum. Sonia Kapadia. CC BY-SA 4.0

The Legacy Museum is located in a former slave auction warehouse, where thousands of Black people were trafficked during the domestic slave trade. The museum employs unique technology to portray the enslavement of African Americans, the evolution of racial terror lynchings, legalized racial segregation and racial hierarchy in America. Visitors encounter replicas of slave pens and hear first-person accounts of enslaved people, along with looking at photographs and videos from the Jim Crow laws, which segregated Black Americans until 1965. The Legacy Museum also explores contemporary issues of inequality, like mass incarceration and police violence. As part of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), the museum is committed to ending mass incarceration and excessive punishment in the United States, with proceeds going toward marginalized communities. “Our hope is that by telling the history of the African American experience in this country, we expose the narratives that have allowed us to tolerate suffering and injustice among people of color,” says Sia Sanneh, member of EJI.

8. African American Military History Museum - Hattiesburg, Mississippi

Circa 1942, the Tuskegee Airmen pose in front of their aircraft. Signaleer. Public Domain.

The African American Military History Museum educates the public about African American contributions to the United States’ military. During World War II, the building functioned as a segregated club for African American soldiers. Transformed in 2009, the museum now commemorates the courage and patriotism of Black soldiers, who have served in every American conflict since the Revolutionary War. Artifacts, photographs and medals tell the story of how African Americans overcame racial boundaries to serve their country. For instance, the World War II exhibit features the Tuskegee Airmen, the first African American soldiers to successfully enter the Army Air Corps.

9. National Voting Rights Museum and Institute - Selma, Alabama

The 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery for the right to vote. Abernathy Family. Public Domain.

In the historic district of Selma, Alabama, the National Voting Rights Museum and Institute honors the movement to end voter discrimination. With memorabilia and documentation, the museum illustrates the struggle of Black Americans to obtain voting rights. In 1965, nearly 600 civil rights marchers crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, hoping to reach Montgomery. However, the day became known as “Bloody Sunday” as local law enforcement attacked peaceful protesters with clubs and tear gas. While the Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawed voting practices that disenfranchised African Americans, many believe voter suppression still exists through strict photo ID laws for voters, a failure to provide bilingual ballots, and ex-felon disenfranchisement laws. By educating the public, the museum hopes to forever dismantle the barriers of voting in the United States.

10. National Underground Railroad Freedom Center - Cincinnati, Ohio

On the banks of the Ohio River, a statue depicts a mother and her child escaping slavery. Living-Learning Programs. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Near the Ohio River, where thousands of slaves traveled in search of freedom, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center reveals the ongoing struggle for autonomy. From the historical vantage point of the Underground Railroad, the museum promotes the modern abolition of slavery. Due to widespread human trafficking, nearly 40 million people are currently enslaved around the world. As stated on the museum’s website, “Despite the triumphant prose of our American history books, slavery didn’t fully end 150 years ago. Today and throughout time, people around the world have struggled for their freedom. Yet, as forms of slavery evolve, so do the imaginations of those fighting for freedom.” Through artifacts, photographs and first-person accounts, the museum introduces the men and women who have resisted slavery. “Invisible: Slavery Today” is the world's first permanent exhibition on the subjects of modern-day slavery and human trafficking, challenging and inspiring visitors to promote freedom today.

Shannon Moran

is a Journalism major at the University of Georgia, minoring in English and Spanish. As a fluent Spanish speaker, she is passionate about languages, cultural immersion, and human rights activism. She has visited seven countries and thirty states and hopes to continue traveling the world in pursuit of compelling stories.

Colorism Shows its Face through India’s Skin Whitening Creams

Since 1975, India has had a market advertising products that can achieve being “fair and lovely” by whitening the skin, but what effect has this had on Indian society?

People on the street in India. Craig J Bethany. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

On June 26, Unilever made the decision to remove the word “fair” from its whitening creams sold throughout India and parts of Asia. It is assumed that the decision to rename the product was due to the global response to the death of George Floyd and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States. For Indians, skin lightening is a painful reminder of their colonized past.

Commercials for whitening creams have advertised the products as the solution to all of life’s troubles. Along with that, they have carried the notion that having darker skin is harmful and will set you back in life. It only perpetuates colorism, when people within the same race discriminate against skin colors. Often, colorism takes on the form of favoritism toward lighter skin shades over darker ones.

Colorism is a byproduct of colonization. From 1858 to 1947, India was under British rule in hopes of extracting the resources that were making India so profitable through the East India Company. Britain took advantage of the wealth by imposing strict policies and limiting government representation across India. However, those that had lighter complexion were favored and often offered more better jobs than those with darker complexions. Britain maintained its control over India until the country’s independence after World War II.

Thus, in 1975, Unilever’s “Fair & Lovely” cream first debuted. Despite a decadeslong appeal toward fair skin, this “luxurious” type of cream would not become popular until the 1990s, when it became more accessible in the form of cosmetic products such as deodorants, creams and at-home treatments. Even though it is a more recent trend, skin lightening still reflects and enforces the mindset of British colonizers. Bollywood even joined the trend by selecting lighter-skinned actors who can “better represent Indian life.” Since the first release of Unilever’s product, the skin lightening industry has become a multimillion dollar market, with some estimates around $4 billion globally, due to the high demands to meet the beauty standards. The highest usage is across Asia and Africa.

Typical usage for skin lightening creams, also known as skin bleaching, is to help reduce the appearance of scars or age spots. In India, though, the products are also used to reduce the melanin levels in one’s skin. Most products must be applied over the course of six weeks to see results. Often, there is a combination of different steroids or chemicals used to help change skin tone.

Research by the World Health Organization has found that mercury is often an active ingredient. Even though it is banned for use in the U.S., other countries do not have much regulation over mercury’s usage. Mercury can cause a range of problems, from neurological to fertility in nature. 1 in 4 skin lightening products made in Asia has been found to contain mercury. Other risks include skin cancer, premature aging of skin, skin thinning and allergic reactions.

Skin lightening treatments at a convenience store. Sophia Kristina. CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0

Additionally, the color of one’s skin in India is critical when it comes to arranged marriages. Often, parents place advertisements in newspapers known as matrimonial ads in order to find potential spouses for their children. Often in these ads, there are descriptions of the child’s skin tone ranging from “fair” to “wheatish,” with “fair” individuals pursued the most. Along those lines, many dating websites for arranged marriages, such as Shaadi.com, allow users to select preferences based on skin tone. However, Shaadi.com representatives did announce earlier this month they were removing the search option.

This is not to say that the skin lightening industry is to blame for colorism today. It has become a deeply-rooted mechanism, with discrimination and racism existing in Indian society since the 1850s. Activists have encouraged the stop of these products’ production, as organizations such as Women of Worth have found that skin lightening practices cause a sharp decrease in self esteem for brown girls.

Eva Ashbaugh

is a Political Science and Gender, Sexuality, and Women's Studies double major at the University of Pittsburgh. As a political science major concentrating on International Relations, she is passionate about human rights, foreign policy, and fighting for equality. She hopes to one day travel and help educate people to make the world a better place.

Protest in Los Angeles. Steve Devol. CC 2.0

How Defamed Statues Reflect Protests Around the World

On May 25, the world erupted in response to the death of George Floyd. That moment and the protests that followed led to actions such as public marches in the face of COVID-19 guidelines and the painting of murals in places as far off as Idlib, Syria. In the past week, however, the most prevalent form of the protests have been the tearing down of statues of figures affiliated with racism.

The Movement Revitalized

The entire world has reacted to the events that happened in Minneapolis, but Floyd’s death only served to highlight current battles against racism. In London, 29-year-old Alex, an organizer for Black Lives Matter U.K., stated that “we stand alone in terms of creating our own moment- not just responding to what’s happened in the U.S.” The United Kingdom was one of the first places to start tearing down statues, sparking a movement that resonated on a global scale.

In Bristol, England, a statue of Edward Colston, known for his involvement with the trans-Atlantic slave trade, was torn down and thrown into the harbor. In Brussels, Belgium, “demonstrators tore down a statue of King Leopold II, the Belgian ruler who killed millions of Congolese people, and hoisted the flag of the Democratic Republic of Congo below it.” In Richmond, Virginia, a statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee has been defaced and ruined. Even in New Zealand, a statue of British Capt. John Fane Charles Hamilton has been defaced and attempted to be torn down because of his killing of thousands of Maori people in the 19th century. Destroying statues is not necessarily a new thing, normally coming about in rebellion when people believe a certain message is being praised when it shouldn’t. “We have as humans been making monuments to glorify people and ideas since we started making art,” says art historian Jonah Engel Bromwich,” and since we started making statues, other people have started tearing them down.” The act of citizens tearing down statues all across the world serves to show the feelings of injustice that many have felt for a long time regarding issues such as racism.

The world has been battling racism for a long time and the events in Minneapolis only brought more attention to antiracist movements. Especially in light of recent events, the destruction and defamation of statues created to honor public leaders has been a common way to showcase discontent. These acts have worked to bring attention to the inequality and problems that exist today as citizens across the world work tirelessly to bring light to problems of racism found in every culture.

Elizabeth Misnick

is a Professional Writing and Rhetoric major at Baylor University. She grew up in a military family and lived in Europe for almost half her life, traveling and living in different countries. She hopes to continue writing professionally throughout her career and publish her writing in the future.