In their fight over marginalized peoples and access to rare minerals, the Congolese military and Rwanda-backed rebels risk triggering a broader regional war in southeast Africa.

Read MoreThe Mountain Gorillas of Bwindi Impenetrable Forest

Photographer Laura Grier adventures among gorillas and lions in Rwanda and Uganda.

There are few places in the world where wild animals are unafraid of humans, and you can view them in their own majesty in the wild without cages, tourist vehicles or controlling their environment. The Gorillas of the Bwindi Impenetrable forest of Rwanda and Uganda are on the top of my list as a place where I have been able to come face-to-face with animals and spend the day with them in their environment. Those moments have been life-changing for me.

I led a group of six women and one man to Rwanda and Uganda on a philanthropic adventure trip; all of the locals affectionately called our one token male “Silverback” since the male Silverbacks gorillas always travel with a harem of female gorillas in the forest.

We started our trip in Kigali, the capital of Rwanda, and had a meal in “Heaven”, the restaurant that was made famous by the book “A Thousand Hills to Heaven,” a memoir about one couple and how they healed a Rwandan village, raised a family near the old killing fields, and built this restaurant named Heaven. The authors, Josh and Alissa, newlyweds at the time, were at a party and received a challenge: “Do you think you can really make a difference here in Africa?”

This memoir inspired me to lead this trip and to see if through adventure, we too could all give back and make a positive impact here in Rwanda and Uganda. So it was only fitting to begin our journey right in this spot.

Our first stop was visiting the female artisan weaving collective, Handspun Hope, who are mostly widowed women from the horrific genocide that happened here in the 1990s. Many men were murdered in a two-week period of time, leaving women and children orphaned and widowed and with no way to provide for themselves. This non-profit created a gorgeous, safe oasis for these women to weave and gather together and purchasing these goods helps them to support their families and communities and help lift them out of poverty.

Due to the genocide, Rwanda has received a lot of aid and tourism help from around the world. We noticed a marked difference in infrastructure and wealth between Rwanda and Uganda; Uganda is by far the poorer neighbor. So we decided to stay in an eco-lodge on the Ugandan side of the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest to help support the country’s tourism, and also receive the benefits of the Ugandan side’s lower price tag.

We spent two days hiking out to see the gorillas. Each morning, groups of trackers leave at sunrise to track the various families of gorillas in the forest, and then a couple hours later we leave in groups to follow their trail and hopefully intercept the great apes. Many of these trackers were once poachers, but now tourist dollars flowing in make the gorillas worth more alive than dead—many poachers have switched to the “good side,” helping to protect these giant creatures.

What I loved was learning about these gorilla groups and how they live. They all have names and very human personalities and soap opera-esque drama. They make nests every night on the ground to sleep in, and often you will find them hanging out in the trees above you. When you do finally spot a group of gorillas, they seem very nonchalant about your presence. It doesn’t matter how many hours it took hiking through thick jungle to find them, once discovered the clock starts ticking and you get only an hour to hang out with them before the rules dictate that you have to leave. You can always spend the next day hiking out to find them again, but you will never know how long that will take. They are always on the move.

Nothing really can describe sitting next to a gorilla in the wild and staring into their faces. They are gentle yet powerful creatures, and more akin to us than different. Their forests are protected through tourism dollars, one of the few times I feel like tourism is truly benefiting wildlife, since the Ugandans and Rwandans have a deep respect for these gorilla groups.

After two days of trekking through thick jungles in the cool, misty mountains looking for gorillas, we drove down into the arid savannas of Uganda to visit the Hanging Lions of Queen Elizabeth National Park. This is the only place on Earth where you will find prides of Ishasha lions just hanging out in the high limbs of Sycamore Fig trees. This is a very rare sight, because this unique group of only about 35 lions is endangered due to threats of human-wildlife conflict and retaliatory snaring and poisoning. We drove around in safari vehicles and witnessed gorgeous wildlife, including herds of elephants and hippos and, of course, very full, very happy lions in the trees.

Laura Grier

Laura is a dynamic Adventure Photographer, Photo Anthropologist, Travel Writer, and Social Impact Entrepreneur. With a remarkable journey spanning 87 countries and 7 continents, Laura's lens captures both the breathtaking landscapes and the intricate stories of the people she encounters. As a National Geographic artisan catalog photographer, Huffington Post columnist, and founder of Andeana Hats, Laura fuses her love for photography, travel, and social change, leaving an impact on the world.

A Brighter Future Emerges 29 Years After Rwanda's Genocide

Rwanda's unwavering determination and spirit shine as a source of optimism for the rest of the world.

Rwanda Genocide Memorial. config manager.CC BY 2.0.

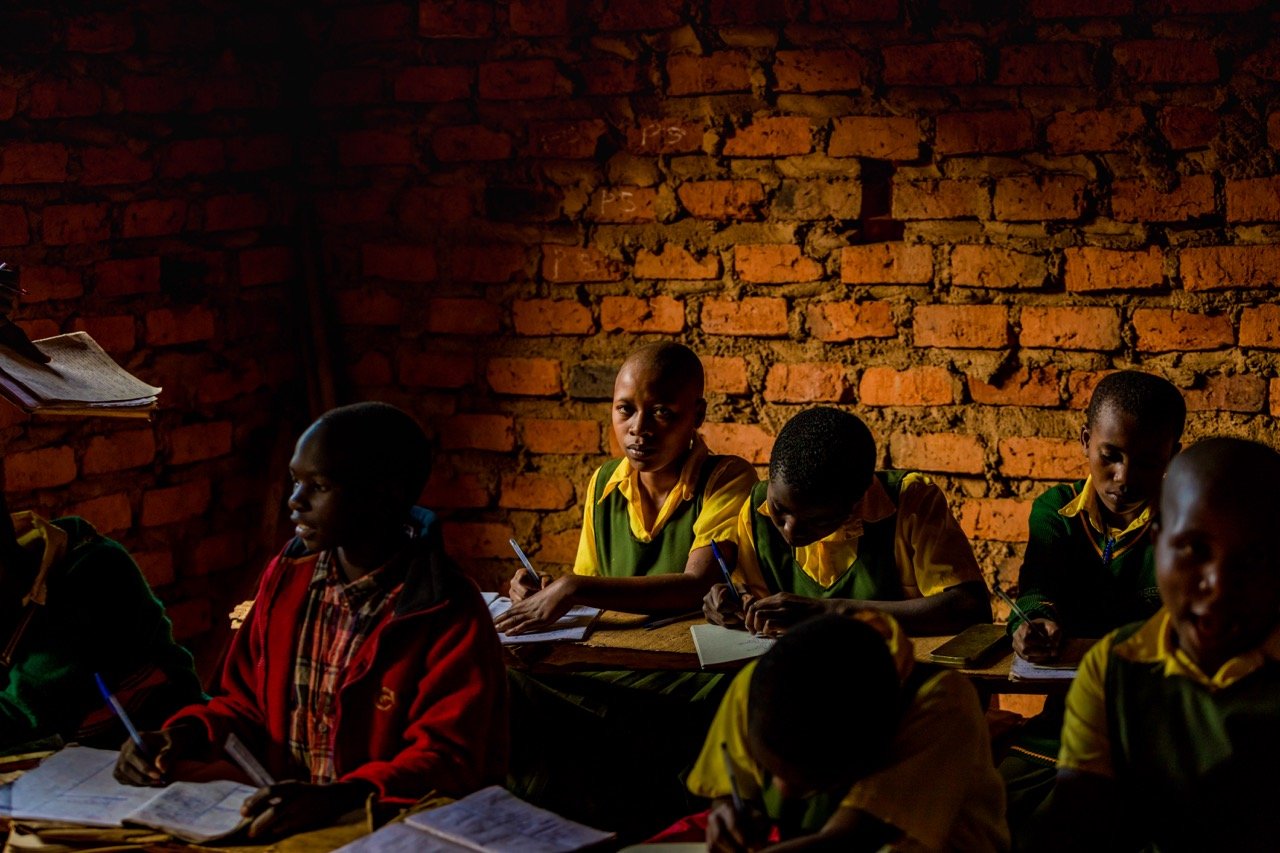

This week marks the 29th anniversary of the Rwandan Genocide, a 100-day period of violence in 1994 in which more than 800,000 people were killed. The repercussions of this tragedy continue to linger, leaving survivors and their family members with deep emotional traumas. Almost 30 years have passed since the devastating genocide in Rwanda, and the country has made some commendable progress in rebuilding its economy and mending its relationships with other nations, while also acknowledging its past mistakes and the sacrifices made during the massacre. The scars of the past may still be visible, but they no longer define Rwanda. Its developments shed light on the country’s journey toward healing and growth, with infrastructure, technology, and education driving its transformation.

The genesis of the Rwanda Genocide three decades ago can be attributed to years of systemic oppression that eventually culminated in one of the most devastating conflicts in modern history. Surprisingly, the two primary ethnic groups involved in this conflict, the Hutus and Tutsis, shared no religious or linguistic differences at the outset. A deep dive into their origins reveals that the Hutus migrated to the Great Lakes region of Central Africa between 500 and 1000 BC, while the Tutsis arrived four centuries later, migrating from the highlands of Ethiopia. The Hutus primarily worked as land cultivators, while the Tutsis were cattle herders, thus creating an economic divide that eventually led to a hierarchical system. In a strange colonial mythology, Tutsi cattle herders were labeled Hamites — a separate and exceptional group — who hailed from an ancient Christian tribe supposedly linked to people of old Palestine. This system placed the Tutsis, as a minority ethnic group, in a position of disproportionate power over the majority Hutus.

Colonial powers subscribed to this concept of racial hierarchy and origin stories, believing the Tutsi to be natural leaders and granting them preferential treatment. After taking Rwanda as a colonial possession in 1897, the German Empire built a power structure that firmly established a hierarchy that favored the Tutsis. They bestowed upon the Tutsis a superior status, owing to their taller stature and lighter skin, giving them greater influence over the Hutus. However, in the aftermath of Germany’s defeat in World War I, Belgium took over the reins of Rwanda’s governance, and, rather than attempting to bridge the cultural divide, exacerbated it. The Belgian administration continued to uphold the Tutsis’ superior status while disregarding the Hutus, creating a further chasm of inequality that only grew wider with time. The introduction of identification cards during the 1930s that explicitly listed one’s ethnicity, for example, further polarized the population, and the stage was set for the tragic events that culminated in the Rwanda Genocide.

In 1973, Rwanda witnessed an event that would forever alter the course of its history. General Juvenal Habyarimana, a Hutu tribe member, rose to power and established the National Revolutionary Movement for Development (NRMD) party to secure his authority. Meanwhile, in Uganda, a group of Rwandan exiles in Uganda who had tasted victory in Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Army during the Ugandan Civil War formed the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). This organization was largely dominated by Tutsi figures and posed a challenge to the incumbent regime. The Rwandan Civil War began, which pitted the Hutu-dominated NRMD government against the primarily Tutsi RPF, while social tensions began to simmer. It was midsummer in 1993 when Hutu extremists hatched their plan, creating a platform for propagating their racist ideology and spewing hatred against the Tutsi people. Thus, Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) came into being, which soon became a tool to incite violence and hatred against the Tutsi, using propaganda and malicious rhetoric.

Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines broadcasted from this office during the Rwanda Genocide. kigaliwire.CC BY-NC 2.0.

April 6, 1994, was the beginning of a nightmare for Rwanda and Burundi. The presidential plane, which was carrying the heads of state of both countries, was hit by gunfire. The news of their deaths, broadcasted by the radical Hutu RTLM radio station, served as a call to arms, sparking a wave of violence against the Tutsi population. The initial attack was planned by a group of military leaders, politicians, and business owners, who were later joined by an increasing number of supporters. This resulted in a devastating genocide, with Tutsis flocking to ostensibly safe havens like churches and administrative centers only to find them transformed into places of horror. 75% of the Tutsi population was wiped out, including many children who were labeled “little rats” and killed alongside adults. The perpetrators killed people of all ages indiscriminately, committing rape and torture on a regular basis. With nowhere to call home, over 2 million people fled the country, including many Hutu ethnic group members, while a million more were internally displaced, leaving 75,000 children orphaned.

The aftermath was massive destruction, with infrastructure reduced to ruins and hundreds of thousands of citizens dead, dealt a crippling blow to progress and development. Rwanda, however, refused to give in to despair. The RPF won the Civil War and took power after four months of horror, ending the genocide. The nation embarked on a journey of healing and reconciliation by embracing a deliberate strategy of transitional justice and transformative programs, characterized by the visionary “Rwanda Vision 2020” campaign launched in 2000. Rwanda embraced a path of renewal through initiatives such as “I am Rwandan,” which encouraged deep reflection on the nation's painful history, acknowledgment of past atrocities, and promotion of healing and reconciliation among all its people. Another example is “Umuganda,” a day of community service in which people from all walks of life work together to improve their communities. Though challenges remained, these initiatives instilled a renewed sense of vigor and solidarity, bringing new life to the difficult task of rebuilding Rwanda.

The modern capital of Kigali is safe, clean, and orderly. Dylan Walters. CC BY 2.0.

Rwanda also undergoes significant changes in its economy. The government has introduced the “Girinka” program, which provides one cow per poor family to combat poverty, with the first female calf being passed on to another family. Poverty has decreased by 23.8 percent from 2000 to 2010, and Rwanda has emerged as one of the fastest-growing economies in Central Africa, with four years of eight percent GDP growth between 2011 and 2014. These developments are positive indicators for Rwanda’s future.

Despite the indelible mark of shame left by the horrific acts, Rwanda has sought reconciliation by embracing its rich heritage of traditional pre-colonial Rwandese customs and values, while also welcoming contributions from the international community. The genocide has prompted profound reflections on critical issues such as the efficacy of peace operations, the urgency of ending international crimes, and the delicate nature of maintaining civility. These pressing issues necessitate international attention and are still relevant today.

TO GET INVOLVED:

World Help: Over the last decade, World Help has worked to bring healing and restoration to Rwandan communities through initiatives like trauma counseling, children’s homes, child sponsorship, construction projects, clean-water wells, sustainable agriculture, vocational training, and more. To learn more and get involved, click here.

IBUKA: IBUKA is an umbrella organization supporting survivors in Rwanda. Representatives from institutions like IBUKA and the National Commission for the Fight Against Genocide are invited to speak at commemorations to provide expert histories and testimonies. To learn more and get involved, click here.

Hope Zhu

Hope is a Chinese international student at Wake Forest University in North Carolina studying sociology, statistics, and journalism. She dreams of traveling around the globe as a freelance reporter while touching on a wide range of social issues from education inequality to cultural diversity. Passionate about environmental issues and learning about other cultures, she is eager to explore the globe. In her free time, she enjoys cooking Asian cuisine, reading, and theater.

VIDEO: Mama Rwanda

Located at the converging point between the African Great Lakes region and East Africa, the Republic of Rwanda is an environmentally, economically and culturally diverse country rebuilding its identity in the wake of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, in which approximately 800,000 Tutsis were killed by Hutu extremists. The country takes pride in its regional fauna, which includes elephants, gorillas, hippos, giraffes and zebras. Travelers interested in viewing Rwandan wildlife can observe it in three national parks: Volcanoes National Park, Nyungwe Forest National Park and Akagera National Park. “Mama Rwanda” also shows Kigali, the capital of Rwanda and the heart of its economic and cultural life. The city boasts a vibrant marketplace and architecture that combines traditional and modern styles. Outside the city, Rwanda’s expansive coffee growing fields are tended by over 450,000 planters. Basket weaving has been an important aspect of Rwandan culture for centuries and is now being used by women impacted by the Rwandan genocide to pursue greater economic independence as producers within an international market. Hutu and Tutsi women have come together to weave baskets, a practice that is now a symbol of national reconciliation. These businesses sell their wares to both small stores and large department stores like Macy’s. The profits of weaving companies are often used to support Rwandan families in need of food and medicine.

The Peace Corps in Rwanda, Part 2

A Peace Corps Christmas in Rwanda

In my last update, I talked a bit about the path that led me to the Peace Corps and the basics of the three-month training program that was my day-to-day life. For a while, most of that remained unchanged. After returning from visiting my final site outside Nyungwe National Park, I was back to the grind of daily Kinyarwanda lessons; classroom management sessions, and any other miscellaneous bit of training that the Peace Corps deemed necessary for its education volunteers.

I mentioned in my first post how the community-based training program, while undeniably effective when it comes to integration and language acquisition, can quickly leave you desperate for just a small taste of the familiar. As soon as we had the chance, we all embraced that ideal wholeheartedly with the help of surprise birthday parties, pumpkin carving for Halloween, a massive collaborative Thanksgiving dinner, and most recently coming back together for Christmas and New Year’s celebrations.

Admittedly, some of the days have felt long and drawn out, but it’s amazing how fast the weeks have flown by. As I write this, my training has finished and I have been officially sworn in as an official Peace Corps Volunteer. After three months of training as a group, we are now scattered around the country in the communities that we will be working in for the next two years. The whole transition is a somewhat bittersweet. While I’m experiencing a freedom that I haven’t had for what seems like an eternity, it also means separating myself from the people, both in my host family and training group, that I’ve grown close to over the past months. In addition, as an education volunteer, I was installed on site during the holiday break. This meant that for a while there was little for me to do but hang out in the school offices or walk around and introduce myself (a bit of a challenge since most of the people in the community assume, at first glance, that I’m the same volunteer that has been working here the past two years).

On top of the conflicts that come from simultaneous feelings of freedom, boredom, and missing friends, I’ve been finding that my site is in an unusual limbo of classic Peace Corps life and unexpected luxury. I can start my day with a bucket bath and hand washing a load of laundry, followed by browsing the web in my school’s modern offices. I can then head up a partially eroded hillside staircase past a couple troops of baboons and struggle to light a charcoal stove in order to cook dinner. I can lounge in my tile-floored house and watch a movie, only to be woken up in the middle of night to chase mice out of the room.

To be clear, none of these are meant as complaints; just the opposite. I was all set to be handling all these things and more, but my assignment here is most definitely not what I was expecting from the Peace Corps (in the best possible way). Just walking around the campus is an experience in itself, with forested hills stretching into the distance as far as the eye can see.

I cannot wait to get started with my work here, although that still seems to be a long way off. While the semester for the rest of my colleagues started last week, I’m here to teach at a school for conservation and environmental management that has the students completing internships around the country for their first month. As a result, I’ve got a nice, long, and quite possibly cabin fever-inducing chunk of time off before I can begin teaching in February.

Thankfully, I’ve been able to stave off boredom by traveling for the holidays, visiting friends and getting to see a bit more of Rwanda in the process. The festivities made it a little more like home with the help of cheap Christmas decorations bought in the capital, a tiny plastic tree, and a can or two of white foam marketed as ‘fake snow’ (a surprisingly good substitute for a white Christmas, once you get past the lingering soap smell in the air). But now the holidays have come and gone and everyone is getting to work for the New Year, so it’s back to site for me. With any luck I’ll be able to find some projects to pass the time and supply me with some good stories moving forward.

READ SCOTT'S FIRST UPDATE ON THE PEACE CORPS IN RWANDA.

SCOTT JENKINS

Scott Jenkins grew up in Ridgewood, NJ and graduated from NYU in 2012 with a degree in Anthropology and Linguistics. His passion for travel, adventure, and helping others led him to apply to the Peace Corps in September of 2012. He was invited to teach in Rwanda, where he is currently serving for the next two years.

The Peace Corps in Rwanda, Part 1

I’ve known for a while now that I wanted to work abroad, even though I only recently figured out what I want to do with my life. I studied Anthropology and Linguistics at NYU, traveled when I could, spent a semester in Ghana, and since graduating in 2012 I had been searching high and low for positions in countless NGO’s, volunteer organizations, ecotourism companies, even the Foreign Service. Nothing was working out, until last September when I applied to the Peace Corps.

Like a lot of people my age, I had heard of the Peace Corps in passing but had never really given it much thought. Young Americans heading off to teach abroad is hardly a novel concept anymore, with more organizations and programs offering that sort of position than you can count. And while I may not have been entirely sure of my future aspirations, being a teacher had never been at the top of my list. Nevertheless, I put in my application and started crossing my fingers to be placed in one of the environmental or agricultural programs run by the Peace Corps. Lo and behold, however, I received my invitation to serve in Rwanda as a secondary school teacher, leaving in September 2013. It wouldn’t have been my first choice, but the more I looked into things and now that I’m here in country, I don’t think I could have asked for better.

When most people (my former self included) think of Rwanda, all that comes to mind is the genocide that took place in 1994. It has been nearly twenty years since that tragedy, however, and the strides that Rwandans have been able to make in that time is nothing short of astonishing. Add to that the natural beauty of the country – mountains, volcanoes, rainforests, and rolling green hills as far as the eye can see – and you have a place that I am beyond lucky to be living in for the next 26 months of my life.

When you join the Peace Corps, you spend three months of training in-country before heading off to your final site. That training is where I am now, about one month into the thick of it. There are 34 volunteers in total here, each of us paired with a different Rwandan host family throughout the district of Kamonyi, a relatively short drive from the capital city of Kigali. I was placed, as were a decent number of my fellow volunteers, with a farming family in one of the many small towns within the district. Most of us have at least limited access to electricity in our homes, although running water is still, and I’m sorry in advance for the pun, a bit of a pipe dream. While this hasn’t been my first brush with bucket baths, hole-in-the-ground latrines, or hand-washing laundry, it still seems surreal to me that this is what life will look like for some time to come.

Day to day, there’s not much variation to speak of. When I’m not spending the day studying the local language of Kinyarwanda I’m listening to a lecture on Peace Corps policy, safety procedures, or the Rwandan education system. I was warned that training feels like the longest and hardest part of service and I’m always looking at the light at the end of the tunnel, but sometimes that’s easier said than done. After a couple days of complete immersion, it’s amazing what a relief it is just to hear a few simple words of English. On the other hand, however, I can’t deny that the Peace Corps approach to language training works like a dream. On my first night here in the village I sat in awkward silence with my host family, occasionally trying my hand at some cross-cultural charades to try to explain something. Now, less than a month later, I can show up to the dinner table and have a pleasant, albeit simple, conversation with my host parents.

A lot of things seem to move slowly around here, but one happy exception to the rule was the early announcement of our final site placements. Just this past week, we were each assigned to our permanent positions throughout the country and given a couple of days off to go visit and get a feel for what our actual service will look like. Since training can tend to seem a bit repetitive, this trip has been a much-needed break in the monotony of Kinyarwanda lessons and technical training. I am beyond ecstatic to announce that I will be teaching at the Kitabi College of Conservation and Environmental Management (KCCEM) in the Nyamagabe District down in the Southern Province. Although my primary job description is still teaching English, my post is incredibly different from all of the others in the country. Rather than a crowded secondary school with classes numbering around fifty young students, KCCEM caters to a small class (only around twenty students in total) of park rangers from Rwanda and the surrounding countries. In addition to teaching English, I will have my choice of any side projects that I might want to try my hand at – an especially exciting prospect given our proximity to Nyungwe National Park, a mountainous rainforest that is home to an overwhelming diversity of flora and fauna. I’m also particularly excited to be able to continue one of my hobbies from home and get involved in the large beekeeping cooperative here in the town of Kitabi.

Having finished my site visit, I know that my time in the Peace Corps will be far from the normal experience that most volunteers have. Even so, I wouldn’t change it for the world – this school is a better fit than I could have ever hoped for and I’m looking forward to making the most of every moment I have here. There will be more updates to come as I make my way through my service and I hope that you’ll all be as excited as I am to see what Rwanda has in store for me.

SCOTT JENKINS

Scott Jenkins grew up in Ridgewood, NJ and graduated from NYU in 2012 with a degree in Anthropology and Linguistics. His passion for travel, adventure, and helping others led him to apply to the Peace Corps in September of 2012. He was invited to teach in Rwanda, where he is currently serving for the next two years.

RWANDA: Sweet Dreams

How does a country distance itself up from the horrors of the past? In post-genocide Rwanda, this has proven to be a tall task. Yet, great strides have been made in the country's economic recovery since the '94 genocide. Pioneering Rwandan theater director Kiki Katese believes though that, "people are not like roads and buildings." 'Sweet Dreams' shows us the truth in her sentiment by following the story of Rwanda's first women-only drumming troupe as they empowerer themselves through a new and foreign venture - the creation of the country's first ever Ice Cream shop.

CONNECT WITH SWEET DREAMS

VIDEO: The Kula Project Invests in Farmers to Help the People of Rwanda

The majority of farmers in developing nations like Rwanda are unable to generate enough income to feed and sustain their families. This is due to the lack of basic needs for success. The Kula Project invests in small-scale farmers in Rwanda to create sustainable communities.

CONNECT WITH KULA PROJECT

VIDEO: Jono Moehlig’s Spoken Poem on the Beauty of Rwanda

Jono Moehlig went on a trip to Rwanda and found that the people he encountered there were some of the most amazing people he has ever met. Watching wartorn killers that have been released and loved by the neighbors they once destroyed, he learned what peace really is.