In their fight over marginalized peoples and access to rare minerals, the Congolese military and Rwanda-backed rebels risk triggering a broader regional war in southeast Africa.

Read MoreThe Mountain Gorillas of Bwindi Impenetrable Forest

Photographer Laura Grier adventures among gorillas and lions in Rwanda and Uganda.

There are few places in the world where wild animals are unafraid of humans, and you can view them in their own majesty in the wild without cages, tourist vehicles or controlling their environment. The Gorillas of the Bwindi Impenetrable forest of Rwanda and Uganda are on the top of my list as a place where I have been able to come face-to-face with animals and spend the day with them in their environment. Those moments have been life-changing for me.

I led a group of six women and one man to Rwanda and Uganda on a philanthropic adventure trip; all of the locals affectionately called our one token male “Silverback” since the male Silverbacks gorillas always travel with a harem of female gorillas in the forest.

We started our trip in Kigali, the capital of Rwanda, and had a meal in “Heaven”, the restaurant that was made famous by the book “A Thousand Hills to Heaven,” a memoir about one couple and how they healed a Rwandan village, raised a family near the old killing fields, and built this restaurant named Heaven. The authors, Josh and Alissa, newlyweds at the time, were at a party and received a challenge: “Do you think you can really make a difference here in Africa?”

This memoir inspired me to lead this trip and to see if through adventure, we too could all give back and make a positive impact here in Rwanda and Uganda. So it was only fitting to begin our journey right in this spot.

Our first stop was visiting the female artisan weaving collective, Handspun Hope, who are mostly widowed women from the horrific genocide that happened here in the 1990s. Many men were murdered in a two-week period of time, leaving women and children orphaned and widowed and with no way to provide for themselves. This non-profit created a gorgeous, safe oasis for these women to weave and gather together and purchasing these goods helps them to support their families and communities and help lift them out of poverty.

Due to the genocide, Rwanda has received a lot of aid and tourism help from around the world. We noticed a marked difference in infrastructure and wealth between Rwanda and Uganda; Uganda is by far the poorer neighbor. So we decided to stay in an eco-lodge on the Ugandan side of the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest to help support the country’s tourism, and also receive the benefits of the Ugandan side’s lower price tag.

We spent two days hiking out to see the gorillas. Each morning, groups of trackers leave at sunrise to track the various families of gorillas in the forest, and then a couple hours later we leave in groups to follow their trail and hopefully intercept the great apes. Many of these trackers were once poachers, but now tourist dollars flowing in make the gorillas worth more alive than dead—many poachers have switched to the “good side,” helping to protect these giant creatures.

What I loved was learning about these gorilla groups and how they live. They all have names and very human personalities and soap opera-esque drama. They make nests every night on the ground to sleep in, and often you will find them hanging out in the trees above you. When you do finally spot a group of gorillas, they seem very nonchalant about your presence. It doesn’t matter how many hours it took hiking through thick jungle to find them, once discovered the clock starts ticking and you get only an hour to hang out with them before the rules dictate that you have to leave. You can always spend the next day hiking out to find them again, but you will never know how long that will take. They are always on the move.

Nothing really can describe sitting next to a gorilla in the wild and staring into their faces. They are gentle yet powerful creatures, and more akin to us than different. Their forests are protected through tourism dollars, one of the few times I feel like tourism is truly benefiting wildlife, since the Ugandans and Rwandans have a deep respect for these gorilla groups.

After two days of trekking through thick jungles in the cool, misty mountains looking for gorillas, we drove down into the arid savannas of Uganda to visit the Hanging Lions of Queen Elizabeth National Park. This is the only place on Earth where you will find prides of Ishasha lions just hanging out in the high limbs of Sycamore Fig trees. This is a very rare sight, because this unique group of only about 35 lions is endangered due to threats of human-wildlife conflict and retaliatory snaring and poisoning. We drove around in safari vehicles and witnessed gorgeous wildlife, including herds of elephants and hippos and, of course, very full, very happy lions in the trees.

Laura Grier

Laura is a dynamic Adventure Photographer, Photo Anthropologist, Travel Writer, and Social Impact Entrepreneur. With a remarkable journey spanning 87 countries and 7 continents, Laura's lens captures both the breathtaking landscapes and the intricate stories of the people she encounters. As a National Geographic artisan catalog photographer, Huffington Post columnist, and founder of Andeana Hats, Laura fuses her love for photography, travel, and social change, leaving an impact on the world.

A Brighter Future Emerges 29 Years After Rwanda's Genocide

Rwanda's unwavering determination and spirit shine as a source of optimism for the rest of the world.

Rwanda Genocide Memorial. config manager.CC BY 2.0.

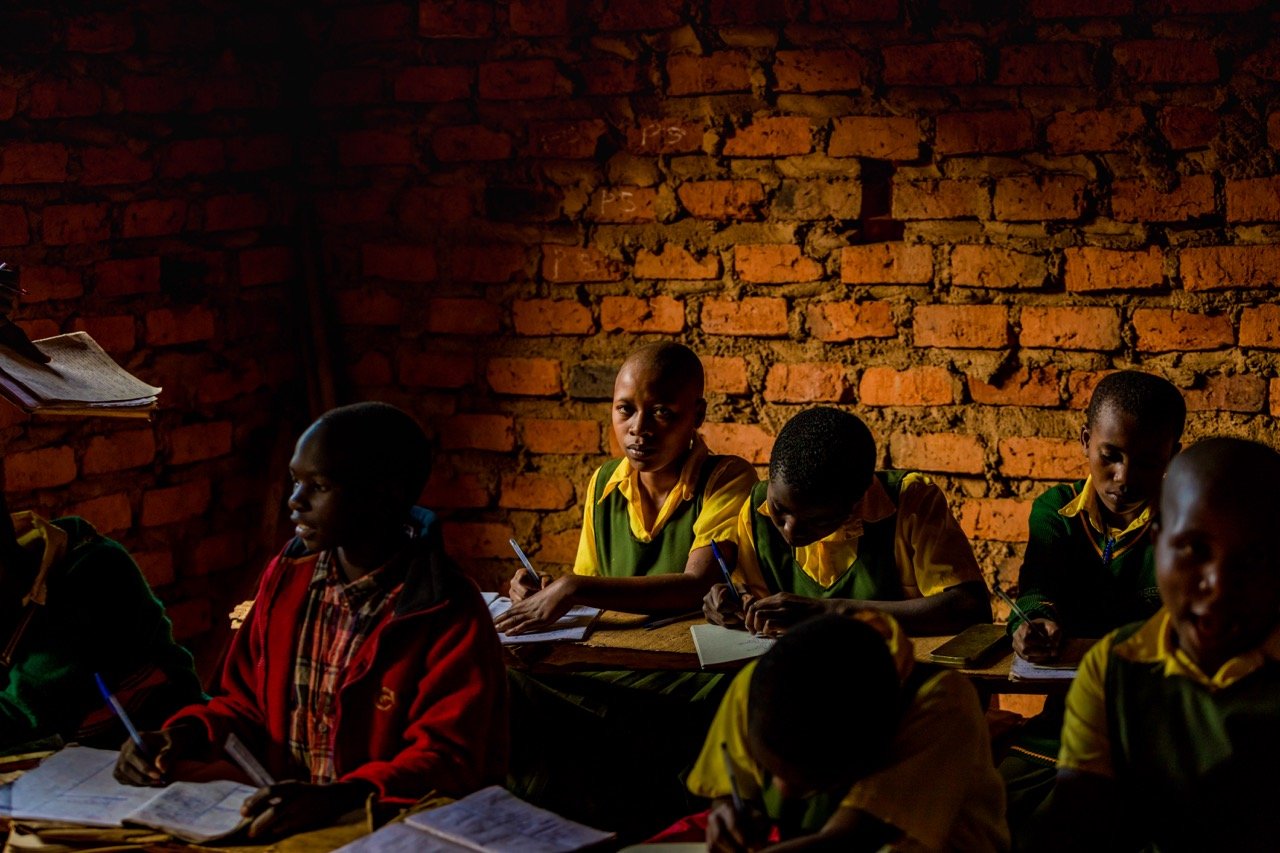

This week marks the 29th anniversary of the Rwandan Genocide, a 100-day period of violence in 1994 in which more than 800,000 people were killed. The repercussions of this tragedy continue to linger, leaving survivors and their family members with deep emotional traumas. Almost 30 years have passed since the devastating genocide in Rwanda, and the country has made some commendable progress in rebuilding its economy and mending its relationships with other nations, while also acknowledging its past mistakes and the sacrifices made during the massacre. The scars of the past may still be visible, but they no longer define Rwanda. Its developments shed light on the country’s journey toward healing and growth, with infrastructure, technology, and education driving its transformation.

The genesis of the Rwanda Genocide three decades ago can be attributed to years of systemic oppression that eventually culminated in one of the most devastating conflicts in modern history. Surprisingly, the two primary ethnic groups involved in this conflict, the Hutus and Tutsis, shared no religious or linguistic differences at the outset. A deep dive into their origins reveals that the Hutus migrated to the Great Lakes region of Central Africa between 500 and 1000 BC, while the Tutsis arrived four centuries later, migrating from the highlands of Ethiopia. The Hutus primarily worked as land cultivators, while the Tutsis were cattle herders, thus creating an economic divide that eventually led to a hierarchical system. In a strange colonial mythology, Tutsi cattle herders were labeled Hamites — a separate and exceptional group — who hailed from an ancient Christian tribe supposedly linked to people of old Palestine. This system placed the Tutsis, as a minority ethnic group, in a position of disproportionate power over the majority Hutus.

Colonial powers subscribed to this concept of racial hierarchy and origin stories, believing the Tutsi to be natural leaders and granting them preferential treatment. After taking Rwanda as a colonial possession in 1897, the German Empire built a power structure that firmly established a hierarchy that favored the Tutsis. They bestowed upon the Tutsis a superior status, owing to their taller stature and lighter skin, giving them greater influence over the Hutus. However, in the aftermath of Germany’s defeat in World War I, Belgium took over the reins of Rwanda’s governance, and, rather than attempting to bridge the cultural divide, exacerbated it. The Belgian administration continued to uphold the Tutsis’ superior status while disregarding the Hutus, creating a further chasm of inequality that only grew wider with time. The introduction of identification cards during the 1930s that explicitly listed one’s ethnicity, for example, further polarized the population, and the stage was set for the tragic events that culminated in the Rwanda Genocide.

In 1973, Rwanda witnessed an event that would forever alter the course of its history. General Juvenal Habyarimana, a Hutu tribe member, rose to power and established the National Revolutionary Movement for Development (NRMD) party to secure his authority. Meanwhile, in Uganda, a group of Rwandan exiles in Uganda who had tasted victory in Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Army during the Ugandan Civil War formed the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). This organization was largely dominated by Tutsi figures and posed a challenge to the incumbent regime. The Rwandan Civil War began, which pitted the Hutu-dominated NRMD government against the primarily Tutsi RPF, while social tensions began to simmer. It was midsummer in 1993 when Hutu extremists hatched their plan, creating a platform for propagating their racist ideology and spewing hatred against the Tutsi people. Thus, Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) came into being, which soon became a tool to incite violence and hatred against the Tutsi, using propaganda and malicious rhetoric.

Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines broadcasted from this office during the Rwanda Genocide. kigaliwire.CC BY-NC 2.0.

April 6, 1994, was the beginning of a nightmare for Rwanda and Burundi. The presidential plane, which was carrying the heads of state of both countries, was hit by gunfire. The news of their deaths, broadcasted by the radical Hutu RTLM radio station, served as a call to arms, sparking a wave of violence against the Tutsi population. The initial attack was planned by a group of military leaders, politicians, and business owners, who were later joined by an increasing number of supporters. This resulted in a devastating genocide, with Tutsis flocking to ostensibly safe havens like churches and administrative centers only to find them transformed into places of horror. 75% of the Tutsi population was wiped out, including many children who were labeled “little rats” and killed alongside adults. The perpetrators killed people of all ages indiscriminately, committing rape and torture on a regular basis. With nowhere to call home, over 2 million people fled the country, including many Hutu ethnic group members, while a million more were internally displaced, leaving 75,000 children orphaned.

The aftermath was massive destruction, with infrastructure reduced to ruins and hundreds of thousands of citizens dead, dealt a crippling blow to progress and development. Rwanda, however, refused to give in to despair. The RPF won the Civil War and took power after four months of horror, ending the genocide. The nation embarked on a journey of healing and reconciliation by embracing a deliberate strategy of transitional justice and transformative programs, characterized by the visionary “Rwanda Vision 2020” campaign launched in 2000. Rwanda embraced a path of renewal through initiatives such as “I am Rwandan,” which encouraged deep reflection on the nation's painful history, acknowledgment of past atrocities, and promotion of healing and reconciliation among all its people. Another example is “Umuganda,” a day of community service in which people from all walks of life work together to improve their communities. Though challenges remained, these initiatives instilled a renewed sense of vigor and solidarity, bringing new life to the difficult task of rebuilding Rwanda.

The modern capital of Kigali is safe, clean, and orderly. Dylan Walters. CC BY 2.0.

Rwanda also undergoes significant changes in its economy. The government has introduced the “Girinka” program, which provides one cow per poor family to combat poverty, with the first female calf being passed on to another family. Poverty has decreased by 23.8 percent from 2000 to 2010, and Rwanda has emerged as one of the fastest-growing economies in Central Africa, with four years of eight percent GDP growth between 2011 and 2014. These developments are positive indicators for Rwanda’s future.

Despite the indelible mark of shame left by the horrific acts, Rwanda has sought reconciliation by embracing its rich heritage of traditional pre-colonial Rwandese customs and values, while also welcoming contributions from the international community. The genocide has prompted profound reflections on critical issues such as the efficacy of peace operations, the urgency of ending international crimes, and the delicate nature of maintaining civility. These pressing issues necessitate international attention and are still relevant today.

TO GET INVOLVED:

World Help: Over the last decade, World Help has worked to bring healing and restoration to Rwandan communities through initiatives like trauma counseling, children’s homes, child sponsorship, construction projects, clean-water wells, sustainable agriculture, vocational training, and more. To learn more and get involved, click here.

IBUKA: IBUKA is an umbrella organization supporting survivors in Rwanda. Representatives from institutions like IBUKA and the National Commission for the Fight Against Genocide are invited to speak at commemorations to provide expert histories and testimonies. To learn more and get involved, click here.

Hope Zhu

Hope is a Chinese international student at Wake Forest University in North Carolina studying sociology, statistics, and journalism. She dreams of traveling around the globe as a freelance reporter while touching on a wide range of social issues from education inequality to cultural diversity. Passionate about environmental issues and learning about other cultures, she is eager to explore the globe. In her free time, she enjoys cooking Asian cuisine, reading, and theater.

The Top 3 Countries For Women in Government

For most of history, men have made up all global governments. However, today, a select few lead the world with more than half of their parliamentary seats being occupied by women.

UN Women’s Event. UN Women Gallery. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

While governments around the world are still generally male-dominated, and men continue to hold most positions of high power, women have made significant strides. Rwanda and Cuba are the only countries in the world with more than 50% of their government being occupied by women today, while Bolivia maintained a female majority from 2014-2019.There are other countries whose highest roles are filled by women. For example, Jacinda Ardern is the prime minister of New Zealand, Sanna Marin is the youngest prime minister ever elected in Finland, Mia Mottley is the first woman elected as prime minister in Barbados, and Katrín Jakobsdóttir is the prime minister of Iceland. However, Rwanda, Cuba and Bolivia are the only three countries led by women in terms of legislative percentages. .

Rwanda

Dr. Usta Kayitesi, Former Deputy CEO of Rwandan Governance Board. Paul Kagame. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

In 2003, Rwanda set a rule that at least 30% of government seats had to be filled by women. That very year, the elections resulted in nearly a 50/50 gender split in Rwanda’s parliament. Ten years later, the Rwandan parliament became 64% female. In 2022, Rwandan parliament is still 61% women.With that being said, women in the Rwandan government say that they still face sexism, despite holding the majority. District Vice Mayor Claudette Mukamana says women’s abilities are still questioned; Executive Secretary for the Rubavu District Berthilde Muruta says their motives for being in government are questioned.

Cuba

Cuban flag in Havana. Samuel Negredo. CC BY 2.0.

In 2018, Cuba followed Rwanda as the second country to elect a female majority parliament. Since 2018, 53% of Cuba’s parliament has been made up of women. Unlike Rwanda, Cuba does not have a quota in place for women in government. Despite the majority-woman parliament, there have been criticisms of Cuba’s treatment of elected women, just like Rwanda, including that the higher up one goes in the government, the less women there are. Essentially, while in terms of pure statistics women dominate Cuba’s government, men continue to occupy the roles with the most political power.

Bolivia

Former Bolivian President of Senate Adriana Salvatierra, third from the left, (insert which one she is in parentheses) at UN Women’s Event. UN Women Gallery. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

In 2020, Bolivia’s proportion of women in parliament equaled 46% and has stayed at that figure since. But from 2014 to 2019, Bolivia was one of the only countries with a majority woman government, at 53%. Like Rwanda, Bolivia has gender quotas, but these quotas are enacted a bit differently in Bolivia versus Rwanda. Bolivia has a quota for the number of female candidates put forward in any given election cycle, as opposed to the number actually elected. For the Lower House, Bolivia requires at least half of the candidates to be women.

Calliana Leff

Calliana is currently an undergraduate student at Boston University majoring in English and minoring in psychology. She is passionate about sustainability and traveling in an ethical and respectful way. She hopes to continue her writing career and see more of the world after she graduates.

VIDEO: Mama Rwanda

Located at the converging point between the African Great Lakes region and East Africa, the Republic of Rwanda is an environmentally, economically and culturally diverse country rebuilding its identity in the wake of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, in which approximately 800,000 Tutsis were killed by Hutu extremists. The country takes pride in its regional fauna, which includes elephants, gorillas, hippos, giraffes and zebras. Travelers interested in viewing Rwandan wildlife can observe it in three national parks: Volcanoes National Park, Nyungwe Forest National Park and Akagera National Park. “Mama Rwanda” also shows Kigali, the capital of Rwanda and the heart of its economic and cultural life. The city boasts a vibrant marketplace and architecture that combines traditional and modern styles. Outside the city, Rwanda’s expansive coffee growing fields are tended by over 450,000 planters. Basket weaving has been an important aspect of Rwandan culture for centuries and is now being used by women impacted by the Rwandan genocide to pursue greater economic independence as producers within an international market. Hutu and Tutsi women have come together to weave baskets, a practice that is now a symbol of national reconciliation. These businesses sell their wares to both small stores and large department stores like Macy’s. The profits of weaving companies are often used to support Rwandan families in need of food and medicine.

What the Arrest of Paul Rusesabagina Means for Peace in Rwanda

Rwanda’s history of violence still looms over its people’s memory. More than 25 years after the end of the Rwanda genocide, political tensions and growing concerns over civil rights are once again threatening the fabric of peace in the country.

Rusesabagina lecturing at the University of Michigan in 2014 in commemoration of the 20th anniversary of the Rwanda genocide. University of Michigan’s Ford School. CC BY-ND 2.0

Paul Rusesabagina, the former manager of the Hotel de Mille Collines in Kigali, Rwanda, was arrested in August 2020. During his time as hotel manager, he saved 1,268 lives during the 1994 Rwanda genocide. Touted as a human rights advocate, he is now being charged with murder, arson and terrorism. Rwanda, still reeling from the heinous ethnic violence that spread across the country 26 years ago, once again finds itself on edge.

It has been more than a quarter of a century since up to 800,000 people were killed in the Rwanda genocide. Many of those slaughtered were part of the country’s Tutsi minority, which was ethnically targeted by Hutu extremists. The international community, including the United Nations, failed to take swift enough action to prevent the further spread of violence, which continued from April to July 1994. Former U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon even publicly expressed shame over the organization's failure to prevent the genocide during a 2014 commemoration ceremony in Rwanda.

In the time since, the country has tried to embark on a reconciliation process to ensure that nothing of such nature will ever occur again. Rusesabagina has since enjoyed international attention for his actions during the genocide. The 2004 film “Hotel Rwanda,” based on the Hotel de Mille Collines, received widespread critical acclaim and catapulted Rusesabagina to global celebrity status. The film was nominated for three Academy Awards, and President George W. Bush even awarded Rusesabagina the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2005.

An estimated 800,000 people were killed in the Rwanda genocide, many of whom were part of the country’s Tutsi minority population. Fanny Schertzer. CC BY-SA 3.0

However, the attention generated by “Hotel Rwanda” and Rusesabagina was not inherently positive, especially for the ruling party of Rwanda. President Paul Kagame, the leader of the Rwandan Patriotic Front, has often been described as a dictator. He has been in power for over 20 years and has been the target of international criticism, including from Rusesabagina. Kagame’s actions toward quelling dissent have become the main focus of scrutiny, especially the jailing of political rivals like Shima Diane Rwigara and Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza. In 2018, an annual European Union human rights report highlighted the presence of civil rights violations in Rwanda, allegations that Kagame wrote off as being “ridiculous.”

Rusesabagina himself is an ardent critic of Kagame. In 2007, he claimed that Kagame was responsible for the assassination of former President Juvenal Habyarimana, whose plane was shot down in 1994. Habyarimana's death created more anti-Tutsi sentiment in Rwanda, galvanizing Hutu extremists to take to the streets and plunging the country into violence. Rusesabagina claimed that Kagame’s possible role in Habyarimana’s assassiniation made him responsible for the hundreds of thousands killed during the genocide.

Now, Rusesabagina is the latest critic to be targeted by the Kagame regime. Rusesabagina, who now lives in San Antonio, was traveling to Burundi to speak to a congregation regarding his experience during the Rwanda genocide. Little did he know that this was a lie, and he was falling into a trap set by Kagame that would lead to his arrest. Rusesabagina had a layover in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, before boarding a flight that he thought was heading to Burundi. In Dubai he met Constantin Niyomwungere, the pastor of the congregation Rusesabagina was supposed to speak to. Together, they took a chartered jet intended for Bujumbura in Burundi. However, when the plane landed, Rusesabagina did not find himself in Bujumbura. Instead, he was in the Rwandan capital of Kigali, where he was immediately arrested by law enforcement officials.

Rusesabagina’s arrest is much more than a simple plot by an authoritarian to eliminate critics; it is a reminder of how fragile the peace and reconciliation process can be. Since the Rwanda genocide, the country has made immense progress in improving living standards. In 2019, life expectancy in Rwanda was 69 years, compared to just 31 years in 1995. Women make up 61% of the country’s legislature, the highest proportion of women holding public office in the world. Literacy rates went from just under 60% in the early 1990s to 73% in 2018. Yet, as Rusesabagina’s arrest shows, Rwanda is still has a lot to overcome to fulfill its vision of a post-genocide future.

Rusesabagina benefited from global visibility that not only catapulted him to fame, but brought attention to Rwanda and the 1994 genocide. His arrest is known because he is known. However, the Kagame administration has a pattern of arresting critics and accusing them of conspiracy against the state. Rusesabagina is just one of many in an increasing number of human rights violations that threaten the landscape of Rwandan peace.

The Rwanda genocide provides a stark reminder of how far the world is yet to come in genocide prevention and reconciliation. There have been U.N. investigations and tribunals, Hollywood glamour and award shows since then. Yet, violence does not crawl back to the shadows when the world shines a spotlight on it. Rather, the international community needs to learn from its mistakes and make sure that Paul Rusesabagina’s arrest does not open a new opportunity for another moment of mass violence.

Aerex Narvasa

Aerex is a current student at Occidental College majoring in Diplomacy and World Affairs with a minor in East Asian Studies. He is passionate about sharing people’s stories through writing, and always strives to learn about new places and cultures. Aerex loves finding new music and exploring his hometown of Los Angeles in his free time.

Investing in War: How Violence Has Turned into a Profitable Business

Violence finds its home most often in some of the poorest places. But money filtrates its way through often gathering in arms businesses and corrupt governments. In recent times, this has been true in many countries throughout Africa and the Middle East. Is the price of death worth it?

Salva Kiir, President of South Sudan. Jenny Rockett. CC BY-SA 1.0.

There is a moral question that has surfaced over the years on whether you would have to choose between the death of someone you loved or thousands of strangers. Most of the time it would be frowned upon if you picked one life at the expense of thousands. But not everybody agrees. That moral standard doesn’t translate when power is involved. Too often the death of innocent people is picked for monetary gain. This isn’t just found with governments often associated with corruption but also can be found in US foreign policy and even in the UN. Just look at the Rwandan Genocide and Iraqi War for example. The US tends to only involve itself in conflict in which it has another interest in, often oil or another economic benefit. In Rwanda, the UN actually left the country when violence broke out and only got re-involved once it reached international attention. After the genocide ended, the country got so much foreign aid that its capital city, Kigali, is being recreated as a post-modern enterprise focused solely on appearance and not reality. This pattern has continued throughout many conflicts. It is, quite frankly, the business of war.

This best current examples of this trend lie in South Sudan and Yemen. The rise of the Arab Spring lead to the intermingling of conflict, with wealthy monarchies fueling and funding neighboring battles. This is seen in both Syria and Libya. The most notable pairing though is the UAE in Yemen. Like most foreign involvement it is motivated by economic gain, namely control of the Red Sea coastline, and military prowess, as presence equals power. The UAE’s influence has led to the risk of starvation for 14 million people and a much more complex civil war. The leaders of militia groups are now benefiting greatly from foreign aid while the gap between rich and poor continues to spread.

South Sudan follows a similar pattern. The civil war has led to leadership on both sides of line pocketing millions and pursuing private business in real estate acquisitions and capital investments. South Sudan’s economy is completely dependent on oil leading to endless conflict over oil reserves and wealth distribution. The war has left over 5 million in need of aid yet little is being done to stop it. When those in charge get nothing but wealth, why save the people?

One of the biggest culprits of profiting from war lies in the companies controlling valuable natural resources. Often these companies are foreign owned and operated and give little thought to the violence surrounding it, focusing only on the influx of cash. These goals often coincide with a repressive regime. A study from the World Bank found that if one-fourth of the country's GDP is from primary commodity exports, the possibility of a civil war increases by 30%. Two examples of this are in Columbia and Tibet. Both areas have repressive governments with Tibet under illegal occupation of China. This has allowed for the expansion of foreign interest in mining in both countries, often with little regard to the surrounding area and the people that live there. In Columbia alone, 68% of displacements occurred in mining areas.

As long as money is involved and there are people, governments, and companies benefitting from war and violence, there is little motivation to change. If only we could learn that you don’t need to fight violence with violence, you fight by combatting the wealth of those with power.

DEVIN O’DONNELL’s interest in travel was cemented by a multi-month trip to East Africa when she was 19. Since then, she has continued to have immersive experiences on multiple continents. Devin has written for a start-up news site and graduated from the University of Michigan with a degree in Neuroscience.

The Peace Corps in Rwanda, Part 2

A Peace Corps Christmas in Rwanda

In my last update, I talked a bit about the path that led me to the Peace Corps and the basics of the three-month training program that was my day-to-day life. For a while, most of that remained unchanged. After returning from visiting my final site outside Nyungwe National Park, I was back to the grind of daily Kinyarwanda lessons; classroom management sessions, and any other miscellaneous bit of training that the Peace Corps deemed necessary for its education volunteers.

I mentioned in my first post how the community-based training program, while undeniably effective when it comes to integration and language acquisition, can quickly leave you desperate for just a small taste of the familiar. As soon as we had the chance, we all embraced that ideal wholeheartedly with the help of surprise birthday parties, pumpkin carving for Halloween, a massive collaborative Thanksgiving dinner, and most recently coming back together for Christmas and New Year’s celebrations.

Admittedly, some of the days have felt long and drawn out, but it’s amazing how fast the weeks have flown by. As I write this, my training has finished and I have been officially sworn in as an official Peace Corps Volunteer. After three months of training as a group, we are now scattered around the country in the communities that we will be working in for the next two years. The whole transition is a somewhat bittersweet. While I’m experiencing a freedom that I haven’t had for what seems like an eternity, it also means separating myself from the people, both in my host family and training group, that I’ve grown close to over the past months. In addition, as an education volunteer, I was installed on site during the holiday break. This meant that for a while there was little for me to do but hang out in the school offices or walk around and introduce myself (a bit of a challenge since most of the people in the community assume, at first glance, that I’m the same volunteer that has been working here the past two years).

On top of the conflicts that come from simultaneous feelings of freedom, boredom, and missing friends, I’ve been finding that my site is in an unusual limbo of classic Peace Corps life and unexpected luxury. I can start my day with a bucket bath and hand washing a load of laundry, followed by browsing the web in my school’s modern offices. I can then head up a partially eroded hillside staircase past a couple troops of baboons and struggle to light a charcoal stove in order to cook dinner. I can lounge in my tile-floored house and watch a movie, only to be woken up in the middle of night to chase mice out of the room.

To be clear, none of these are meant as complaints; just the opposite. I was all set to be handling all these things and more, but my assignment here is most definitely not what I was expecting from the Peace Corps (in the best possible way). Just walking around the campus is an experience in itself, with forested hills stretching into the distance as far as the eye can see.

I cannot wait to get started with my work here, although that still seems to be a long way off. While the semester for the rest of my colleagues started last week, I’m here to teach at a school for conservation and environmental management that has the students completing internships around the country for their first month. As a result, I’ve got a nice, long, and quite possibly cabin fever-inducing chunk of time off before I can begin teaching in February.

Thankfully, I’ve been able to stave off boredom by traveling for the holidays, visiting friends and getting to see a bit more of Rwanda in the process. The festivities made it a little more like home with the help of cheap Christmas decorations bought in the capital, a tiny plastic tree, and a can or two of white foam marketed as ‘fake snow’ (a surprisingly good substitute for a white Christmas, once you get past the lingering soap smell in the air). But now the holidays have come and gone and everyone is getting to work for the New Year, so it’s back to site for me. With any luck I’ll be able to find some projects to pass the time and supply me with some good stories moving forward.

READ SCOTT'S FIRST UPDATE ON THE PEACE CORPS IN RWANDA.

SCOTT JENKINS

Scott Jenkins grew up in Ridgewood, NJ and graduated from NYU in 2012 with a degree in Anthropology and Linguistics. His passion for travel, adventure, and helping others led him to apply to the Peace Corps in September of 2012. He was invited to teach in Rwanda, where he is currently serving for the next two years.

RWANDA: Sweet Dreams

How does a country distance itself up from the horrors of the past? In post-genocide Rwanda, this has proven to be a tall task. Yet, great strides have been made in the country's economic recovery since the '94 genocide. Pioneering Rwandan theater director Kiki Katese believes though that, "people are not like roads and buildings." 'Sweet Dreams' shows us the truth in her sentiment by following the story of Rwanda's first women-only drumming troupe as they empowerer themselves through a new and foreign venture - the creation of the country's first ever Ice Cream shop.

CONNECT WITH SWEET DREAMS

VIDEO: The Kula Project Invests in Farmers to Help the People of Rwanda

The majority of farmers in developing nations like Rwanda are unable to generate enough income to feed and sustain their families. This is due to the lack of basic needs for success. The Kula Project invests in small-scale farmers in Rwanda to create sustainable communities.

CONNECT WITH KULA PROJECT

VIDEO: Jono Moehlig’s Spoken Poem on the Beauty of Rwanda

Jono Moehlig went on a trip to Rwanda and found that the people he encountered there were some of the most amazing people he has ever met. Watching wartorn killers that have been released and loved by the neighbors they once destroyed, he learned what peace really is.