In India, where the coronavirus lockdown affects 1.3 billion people, the effect is a big contrast to a place where the city streets are normally thronged with life in all its guises.

Read MoreDivyakant Solanki/EPA

Divyakant Solanki/EPA

In India, where the coronavirus lockdown affects 1.3 billion people, the effect is a big contrast to a place where the city streets are normally thronged with life in all its guises.

Read More

"Indian Flag at Sriperumbdur" by rednivaram is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Almost three weeks after religious violence erupted in Delhi, India, thousands of Muslims are still displaced, most living in relief camps that are overwhelmed by the number of people who have lost everything.

Hindu mobs attacked neighborhoods in the northeast area of New Delhi on Sunday, February 23, 2020. At least 53 people have been killed and more than 200 injured in what is being called the worst violence New Delhi has seen in decades. The three days of violent attacks included the torching and looting of schools, homes, mosques, and businesses. “Mobs of people armed with iron rods, sticks, Molotov cocktails and homemade guns ransacked several neighborhoods, killing people, setting houses, shops and cars on fire”, according to CBS News. The New York Times reported, “Gangs of Hindus and Muslims fought each other with swords and bats, shops burst into flames, chunks of bricks sailed through the air, and mobs rained blows on cornered men.” These attacks came after months of mainly peaceful protests by people of all faiths over changes to citizenship laws that allowed discrimination against Muslims.

The new law, called the Citizenship Amendment Bill, uses a religious test to determine whether immigrants from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan can be considered for expedited Indian naturalization. All of South Asia’s major religions were included—except Islam. According to CBS News, those who oppose the law say, “it makes it easier for persecuted minorities from the three neighboring nations of Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh to get Indian citizenship - unless they are Muslim.” Kapil Mishra, a local Hindu politician of the Hindu nationalist party, the Bharatiya Janata Party, told India’s police that they needed to break up the protests against the law, or he and others would take it into their own hands.

Doctors at the Mustafabad Idgah camp (one of the largest camps) are reporting that many of the survivors are showing early signs of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and depression. The makeshift relief camps are overcrowded and undersupplied, and are lacking in some sanitation amenities. Due to the lack of hygiene amenities, many are suffering from urinary tract infections and skin rashes. The lack of basic hygiene amenities is even more dangerous and deadly amid the global coronavirus pandemic.

Muslims found help from another religious minority in India: Sikhs. A Sikh man, Mohinder Singh, and his son, Inderjit, helped sixty people get to safety by tying turbans around their heads so they would not be recognized as being Muslim. Sikhs themselves experienced large-scale religious violence in October 1984 when 3,000 Sikhs were killed in Delhi after the assassination of then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Khalsa Aid, a non-profit organization founded upon Sikh principles, was one of the first groups to provide aid to the victims. Members of the organization helped by assisting in repairing looted and damaged shops. They also opened a “langar”, a Sikh term for a community kitchen that serves free meals to all visitors—regardless of religion, caste, gender, or ethnicity.

Asiya Haouchine

is an Algerian-American writer who graduated from the University of Connecticut in May 2016, earning a BA in journalism and English. She was an editorial intern and contributing writer for Warscapes magazine and the online/blog editor for Long River Review. She is currently studying for her Master's in Library and Information Science.

@AsiyaHaou

In one of the most beautiful places on Earth, the conflict in Kashmir – which have been largely forgotten by the world – has raged on since 1947. What was once a paradise, Kashmir Valley is now the forgotten epicenter of war, human-rights violations and a true representation of what it looks like to struggle for peace and freedom. Watch this short video about the beauty and conflict of Kashmir.

Read More

Activists and local volunteers meet and console Assamese villagers who might have lost their Indian citizenship. Anuradha Sen Mookerjee, Author provided

The state of Assam in India is currently burning with violent protests against a new citizenship law passed by both houses of the Indian parliament in early December.

The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) will ease the Indian citizenship process for undocumented migrants in India who come from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh – but only for those who are not Muslim, undermining the promise of equality by the Indian Constitution. The international community criticised the new law, with the UN High Commissioner of Human Rights calling it “fundamentally discriminatory”.

Since its parliamentary approval on December 12, the law has triggered massive protests across India including in the capital Delhi.

Assam is directly affected by the new law. It significantly undermines the National Register of Citizens (NRC), a listing process that has been underway in Assam since 2015 through which residents have to prove their claim to citizenship based on documentary evidence. The NRC is designed to update a first list conducted as an all-India exercise in 1951 to combat illegal immigration flows, primarily from neighbouring Bangladesh.

More than 1.9 million people in Assam – many of whom are Muslim – have failed to make it onto the NRC’s final list which was published on August 31. They now face the risk of statelessness. But at the same time, the large numbers of Hindus who were excluded in the NRC system can now become Indian citizens under the CAA.

The way the CAA is written makes way for Indian citizenship of all non-Muslims who lived in certain areas of Assam, such as the Brahmaputra Valley, before or on December 31 2014, even if they don’t have documentary evidence, and while rendering Muslims stateless. It contradicts the cut-off date for inclusion used by the NRC, which was midnight on March 24 1971.

For the protesters on Assam’s streets, the CAA gives legal rights to the large numbers of undocumented Bengali-speaking Hindus who have migrated from Bangladesh since 1971 and also those currently excluded by the NRC.

Their fear is twofold. First, indigenous Assamese feel that with the inclusion of the Bengali speaking Hindus by the CAA, the composite number of Bengali speaking people (both Hindus and Muslims) will outnumber the Assamese speaking people in the state. Census data shows that the Assamese-speaking people in the state declined from 58% of the population in 1991 to 48% in 2011. Second, the Muslims both excluded by NRC and those who have migrated later, risk becoming stateless.

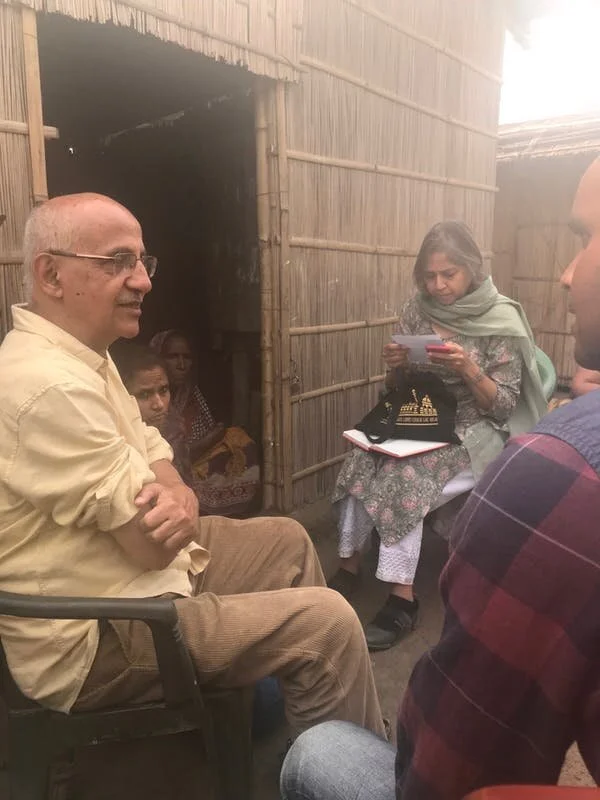

I’ve seen up close the damage the NRC process has had on communities in Assam. In mid-November, I visited the state with the Indian peace activist Harsh Mandar and several others as part of an initiative called Karwan e Mohabbat, a human caravan of peace, justice, solidarity and consciousness as part of my research on citizenship in the Indian borderlands.

We visited the homes of people who have been excluded from the NRC, particularly from the Muslim community in Lower Assam districts. We listened and learned about their experiences of trauma, suffering and hopelessness with the filing of their documents and how they are coping with their exclusion.

Among the people we met in the Barpeta district of Lower Assam were inhabitants of the Chars, low-lying temporary sand islands formed by silt deposition and erosion. These sand bars, which emerge and submerge in the river beds of Assam’s Brahmaputra river, are uniquely vulnerable to disasters such as floods and cyclones.

Pampara Char, one of the silt islands on the Brahmaputra river, Barpeta district, Lower Assam. Google Maps

The Pampara Char is a barren wasteland, with wild grass growing all over the place and houses that looked like temporary huts. The only brick building, which was freshly painted in white and blue, was the primary school. It stood distinct from the other houses and seemed sparingly used. The people, toughened by poverty and harsh ecology, were left distraught by their experience of the NRC and gathered around Harsh Mandar and other social activists to share their suffering and tales of horror about the registration process. Many had to go through repeated verification across different drafts of the list.

View of the fields in one of the village visited in Pampara Char. Anuradha S.Mookerjee, Author provided

I observed deep anxiety among the people we met, such as the aggrieved 54-year-old Khaled Ali. Illiterate and landless, Ali is a river fisherman who sometimes also works as a daily wage labourer. Like many others he received a notice in early August that he and his 18 other family members needed to submit more documents or they would be excluded from the final NRC list. Their names had been included in two previous versions.

A reverification hearing was scheduled for the next day in the distant town of Golaghat, which is 460km away from the Pamapara Char. Overnight, Ali raised a loan of 30,000 Indian rupees (US$424 or €383) to travel to Golaghat, with all his family members and two witnesses in a hired bus. After an 18-hour trip, they reached Golaghat and were received by local civil society activists who arranged for them to camp at a community centre and also helped them to submit their documents.

After their reverification hearing, Ali and his family members found themselves excluded in the final NRC list. While they have 120 days to appeal against their exclusion, his wife lamented that they lack the money to produce more documents from paralegals to support their cases before the appeal deadline on December 29. Meanwhile, a distraught Ali told us that he still has a loan of 14,000 rupees (US$198 or €178) to repay.

Harsh Mander and other social activists listening to the plea of the Char villagers. Anuradha S.Mookerjee, Author provided

For marginal and illiterate residents of the Chars such as Ali, the NRC and the process of proving citizenship has become a very stressful and expensive burden. As we found out during our home visits, a new parallel economy of document production has flourished. Paralegals charged anywhere between 500 to 1,000 Rupees for each document, a very large sum for these poor people.

The highly complex documentation process, which includes requirement for family trees and residency documents dating back to before March 24 1971, is also to blame for the exclusion of large numbers of people from the final NRC register. The process is extremely insensitive to the difficulties of the large mass of illiterate and poverty-stricken populations who are finding it very difficult to make sense of how to navigate registration on their own.

Processes of verification and reverification have been implemented in a way that firmly establish a hierarchical relation between the state and its citizens, with the complete domination by bureaucrats and public office holders over the rights of the citizens and residents.

Many of the marginalised populations in Lower Assam, such as Ali and his family, have needed constant support to be able to file their documents and fight their cases.

Local activists are playing a significant role in helping people deal with the burden of proving their citizenship, understanding the terminology and filling in the application forms and claims. They are also offering guidance about attending case hearings, support in procuring documents for submission from paralegals and also offering psycho-social counselling.

In Barpeta, volunteer Shahjahan Ali Ahmed receives an award from social activist Uma Shankari in recognition of his work helping people left out of the NRC. Anuradha S.Mookerjee, Author provided

Volunteers and human rights groups of Lower Assam have also connected with civil society actors in Upper Assam to help residents commute from Lower to Upper Assam for hearings and verification, and on some occasion even raise money, creating a solidarity network.

Such a humanitarian network is crucial at a time when marginalised people feel threatened with the changing legal regime which seeks to redefine the basis of Indian citizenship. These networks of solidarity in India’s north-eastern borderlands attempt to draw out the real Indian body politic, reinforcing the plural fabric of the Indian constitution.

Anuradha Sen Mookerjee is a Research fellow, Graduate Institute – Institut de hautes études internationales et du développement (IHEID)

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

The Sheroes' Hangout is a cafe in India that is operated entirely by acid attack survivors. Located a few minutes from the Taj Mahal, it is a place of self-growth and empowerment for its employees. While many of India's acid attack survivors struggle to find employment, Sheroes' Hangout offers them a job and a supportive community.

In India, the proportion of women in paid work is among the lowest in the world, at just over 23% – a figure which contrasts sharply with the corresponding rate of over 78% for men.

Opportunities for women to enter employment in the country are limited by a range of factors. These include a dominant tradition of female domestic responsibility, and a prevailing social patriarchy.

Deeply entrenched cultural expectations mean that women are more likely to stay at home. And when they do work, it is mainly on an informal basis, without the luxury of secured wages and contracts.

Against this backdrop, the idea of female entrepreneurship in India faces major challenges. Setting up a business can require significant efforts outside of normal work times, and can lead to women being perceived as irresponsible if they dedicate time to entrepreneurial activities.

But it seems as if things may be changing. My research on women entrepreneurs in India reveals they are contesting social, cultural and family pressures to challenge the status quo in Indian society. They are also empowering other women while providing innovative solutions to major social problems.

Some of the women I spoke to greatly inspired me with their stories. One manufacturing business founder, Pinky Maheshwari, was challenged by her son to make environmentally friendly paper. She went on to create handmade paper made out of cotton that is embedded with seeds. These can then be planted and grown into trees when the paper has served its purpose.

Her award-winning ideas have won appreciation and support from the highest levels of Indian government. She is, she told me, motivated by the idea of empowering others, and “hires women from rural and small towns so that they earn a livelihood and get acknowledged for their creativity”.

She added: “I have employed largely women and I support them in any way I can.”

A similar spirit shone through other women entrepreneurs I interviewed. Padmaja Narsipur, the founder of a digital marketing strategy firm, supports women “re-starters” to join her workforce after a break in their working lives.

She said: “Women re-starters are highly qualified and committed. I have been one myself. I have built a workplace where trust in employees, giving flexible hours, work from home options, is built into the DNA and it is paying off.”

The CEO of Anthill creations, Pooja Rai has a vision to create “interactive learning environments in public spaces with a primary focus on sustainability”, by using recycled materials to build accessible play areas in remote parts of India.

These are just some of the many Indian women entrepreneurs I met who are creating businesses of real purpose. Despite the cultural obstacles, they are changing perceptions and creating innovative businesses that have a real impact on their communities and beyond.

Their work is rewriting the rules for business, families and society while challenging the mindset that there is limited scope for them to create good businesses.

With a blend of social purpose and business acumen, Indian women are embarking on a journey to change perceptions and creating prosperity for themselves and for the nation.

This is the new face of women entrepreneurship in India. And there is evidence that public policy is increasingly supportive of this transformation while society is beginning to celebrate their successes.

Indian society is gradually becoming progressively egalitarian with much needed government initiatives such as “Beti Padhao, Beti Bachao” (Save the Daughter, Educate the Daughter) designed to improve the prospects of young girls.

Improved access to social media, education, and social enterprises are all contributing to change. These are giving momentum to the aspirations of women entrepreneurs in India.

MILI SHRIVASTAVA is a Lecturer in Strategy at Bournemouth University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

At the height of the Cold War, amidst growing tensions between the US and Russia, Indian Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi traveled to Washington D.C to deliver a pragmatic speech on the subjects of communication, understanding and friendship.

35 years later, with increasing polarization around the globe, her simple yet elegant message has never felt so relevant.

However, it is in India, where Indira Gandhi's message still rings most true; somehow managing to make sense of a beguiling and beautifully chaotic society, with a rich reputation of inspiring swathes of Western visitors.

Shot during a two month backpacking trip, with minimal camera equipment, this is the filmmaker’s (Simon Mulvaney) attempt to communicate the beauty of Indira's home country, along with the resonating themes she touched upon all those years ago.

A journey across the Land of Kings "Rajasthan, India". See the wonders of Agra, Jaipur, Jodhpur & Jaisalmer through the videographer’s eyes.

Kashmiri Muslims shout slogans during a protest after Eid prayers in Srinagar. AP Photo/ Dar Yasin

India recently enacted a law which will end a special autonomous status given to the state of Jammu and Kashmir, known in the West as simply “Kashmir.”

Amit Shah, India’s minister for home affairs, announced in Parliamentthat the Bharatiya Janata Party government was revoking Article 370 of the Indian Constitution in the name of bringing prosperity to the region.

Since 1954, this article has governed federal relations between India and Kashmir, India’s only Muslim majority state.

I’m a scholar of South Asian politics and have written extensively on the evolution of the India-Pakistan conflict in Kashmir.

Article 370 is woven into that history.

Article 370 originated in the particular circumstances under which the former prince and last ruler of Kashmir acceded to India shortly after the partition of the British Indian Empire into the independent states of India and Pakistan in 1947.

The prince, or maharaja, agreed to have Kashmir become part of India under duress. His rule was threatened by an insurrection supported by Pakistan.

Article 370 was designed to guarantee the autonomy of the Muslim majority state, the only one in predominantly Hindu India. The clause effectively limited the powers of the Indian government to the realms of defense, foreign affairs and communications. It also permitted the Kashmiri state to have its own flag and constitution.

More controversially, Article 370 prohibited non-Kashmiris from purchasing property in the state and stated that women who married non-Kashmiris would lose their inheritance rights.

But the independence of the Kashmiri state has been declining for decades. Beginning in the early 1950s, a series of presidential ordinances, which had swift effect much like American executive orders, diluted the terms of the article.

For example, in 1954, a presidential order extended Indian citizenship to the “permanent residents” of the state. Prior to this decision the native inhabitants of the state had been considered to be “state subjects.”

Other constitutional changes followed. The jurisdiction of the Indian Supreme Court was expanded to the state in 1954. In addition, the Indian government was granted the authority to declare a national emergency if Kashmir were attacked.

Many other administrative actions reduced the state’s autonomy over time. These have ranged from enabling Kashmiris to participate in national administrative positions to expanding the jurisdiction of anti-corruption bodies, such as the Central Vigilance Commission and the Central Goods and Services Act of 2017, into the state.

What has happened as a result of the move to revoke Article 370?

Kashmiris living in New Delhi gather for a function to observe Eid al-Adha away from their homes in New Delhi. AP Photo/Manish Swarup

Kashmiris living in New Delhi gather for a function to observe Eid al-Adha away from their homes in New Delhi. AP Photo/Manish Swarup

The decision has been met with considerable unhappiness and resentment in the Kashmir Valley, which has a Muslim population close to 97% – versus 68% of the population of the state as a whole. The government of Jammu and Kashmir, meanwhile, does not have the legal power to challenge the move.

China and Pakistan have expressed displeasure.

Pakistan has long maintained that it should have inherited the state based upon its geographic contiguity and its demography.

India and Pakistan have fought three wars over Kashmir. While I don’t believe Pakistan will initiate another war with India over this issue at this time, I doubt it will quietly resign itself to the changed circumstances. At the very least, it will seek to draw in members of the international community to oppose India’s action, as it has sought to do in the past.

China, which considers Pakistan to be its “all-weather ally,” has stated that the decision was “not acceptable and won’t be binding.”

SUMIT GANGULY is a Distinguished Professor of Political and the Tagore Chair in Indian Cultures and Civilizations at Indiana University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION.

Section 377 under the India Penal Code hungover LGBTQ+ lives for years, criminalizing their very existence to exist. Lawyers Menaka Guruswamy and Arundhati Katju fought to change that—and won.

Pride flag in New Delhi, India. Nishta Sharma. Unsplash.

Since 1861, when India was under British colonial rule, there was a section of the India Penal Code that crimilized homosexualtiy as it was “against the order of nature”. In 2013, protestors fought for the code to be recognized as unconstitutional in the eyes of the law, but in a historic case titled Suresh Kumar Koushal vs. Naz Foundation, the Bench stated “We hold that Section 377 does not suffer from… unconstitutionality and the declaration made by the Division Bench of the High Court is legally unsustainable.” Although they would not mark it unconstitutional, the Bench also stated, “Notwithstanding this verdict, the competent legislature shall be free to consider the desirability and propriety of deleting Section 377 from the statute book or amend it as per the suggestion made by Attorney-General G.E. Vahanvati.” To put in more simple terms, the Bench wanted to redirect who made the decision, and stated the matter should be decided by Parliament, itself, not just the judiciary.

In 2016, the case was revisited by three Court members and they decided to pass it on to a five-member court decision. It was not until a year later when the LGTBQ+ community of India saw results. In 2017, in the Puttuswamy case, the Court ruled that “The right to privacy is implicit in the right to life and liberty guaranteed to the citizens of this country by Article 21” - a historic decision which overruled a previous case that said there is no right to privacy in India. The Court also found that “sexual orientation is an essential attribute of privacy. Discrimination against an individual on the basis of sexual orientation is deeply offensive to the dignity and self-worth of the individual. Equality demands that the sexual orientation of each individual in society must be protected on an even platform. The right to privacy and the protection of sexual orientation lie at the core of the fundamental rights guaranteed by Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Constitution.” Essentially, they condemned discrimintion and give validity to the rights of the LGTBQ+ community.

It wasn’t until September 2018, though, when the Court ruled “in so far as it criminalises consensual sexual conduct between adults of the same sex” in the Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India case. According to an article in the Guardian, chief justice Dipak Misra stated that “Criminalising carnal intercourse under section 377 Indian penal code is irrational, indefensible and manifestly arbitrary”. Misra goes on to say “Social exclusion, identity seclusion and isolation from the social mainstream are still the stark realities faced by individuals today, and it is only when each and every individual is liberated from the shackles of such bondage … that we can call ourselves a truly free society.”

Now, a year later, two lawyers who worked on dismantling Section 377 came out as a couple. In an interview with CNN’s Fareed Zakaria, Menaka Guruswamy and Arundhati Katju announced that they were a couple. Ms. Guruswamy stated that they fought so hard because "That was when [they] decided that [they] would never let the LGBT Indians be invisible in any courtroom".

The couple’s decision to come out was met with raved support, one user on Twitter congratulated them and added, “Personal is indeed political”. Which is true - queer people anywhere are responsible for queer people everywhere because to fight for the rights the community deserves, the community must do it as a unit, rather than individually.

Menaka Guruswamy and Arundhati Katju’s accomplishments are not limited by the strides they have made with Section 377, but also with the visibility they have given to the LGBTQ+ community - in India and across the world. They represent the strength and power the LBGTQ+ community has when they preserve despite the setbacks.

OLIVIA HAMMOND is an undergraduate at Emerson College in Boston, Massachusetts. She studies Creative Writing, with minors in Sociology/Anthropology and Marketing. She has travelled to seven different countries, most recently studying abroad this past summer in the Netherlands. She has a passion for words, traveling, and learning in any form.

Each year, about 8 million tons of flowers are dumped into India’s rivers. As flowers hold a sacred place in Hindu rituals, they are often thrown into the Ganges, India’s holiest river. Unfortunately, pesticides and other chemicals from these flowers are mixing with the water, exacerbating an ecosystem already plagued with pollution. Enter HelpUsGreen, an organization that has begun collecting the waste flowers and upcycling them into products like incense, soap and biodegradable styrofoam. Through the group’s efforts, they’re addressing an environmental threat while giving the flowers a new life.

For many Indians, lack of access to menstrual products is compounded by entrenched societal stigma. Across the country, women are beginning to make a change.

A sign in Bali, Indonesia, demonstrates stigmatization of menstruation in the Global South. dominique bergeron. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

For most people with periods in the Western world, menstruation is something of an afterthought—annoying and sometimes painful, but easily dealt with, and far from debilitating. In parts of the Global South, however, “that time of the month” is not only a serious health concern and financial impediment but also a source of profound social and cultural tension. Over the past two years, grassroots activists have brought increased attention to the plight of menstruating women in India, and begun to envision a future in which well-being and participation in society is not dictated by one’s reproductive cycle.

Shameful attitudes toward menstruation in India are deeply ingrained, and, especially in rural areas, can be actively harmful to women of all ages. Indian women experiencing their periods can be banned from entering the kitchen and preparing food, separated from family members, and removed from religious ceremonies, sometimes on the grounds of theistic tradition: In 2018, many Indian men were outraged at a ruling by the country’s Supreme Court allowing women of menstruating age to visit Sabarimala, a Hindu temple in Kerala dedicated to Lord Ayyappa, who is seen in traditional mythology to be disgusted by the concept of female fertility. Indignation at the ruling reached a peak in January 2019, when one person died and dozens were injured in protests against the judgment.

Equally dangerous, and highly imbricated with traditional views of menstruation, is the pervasive lack of access to sanitary products, which are crucial to keeping women clean and safe during their periods. An estimated 70 percent of Indian women are unable to afford such products, with 300 million resorting to unhygienic options such as newspapers, dry leaves, and unwashed rags. Menstruation is also a key driver of school dropouts among girls, 23 percent of whom leave their schooling behind upon reaching puberty.

Cost barriers can prevent Indian women from acquiring menstrual products. Marco Verch. CC BY 2.0

In a sociocultural landscape where natural bodily functions are affecting the human dignity of people with periods, education, outreach, and access are crucial. In February 2018, Indian news outlet Daijiworld reported on one person working toward these goals: the so-called “Pad Woman” of Manguluru, who has been leading a group of young students in her southwestern port to create awareness of menstrual hygiene. The Pad Woman, Prameela Rao, is the founder of non-profit Kalpa Trust, which offers students at the Kavoor government First Grade College materials to manufacture sanitary pads for women in rural areas. The completed pads are distributed free of charge to the colonies of Gurupur, Malali, Bajpe, and Shakthinagar, obviating the need for women to purchase prohibitively expensive mainstream menstrual products. The pads are made from donated cotton clothing, which the students wash, iron, cut, and stitch to create the final product.

In the western state of Gujarat, an organization known as the Aga Khan Rural Support Program (AKRSP) is directly targeting period taboos among rural communities. Activists Manjula and Sudha told the Indian magazine The New Leam that, for the girls they have educated in the villages of Karamdi Chingaryia and Jariyavada, confusion and fear regarding menstruation have given way to confidence and clarity. For the AKSRP, which emphasizes gender equality and the societal participation of women, offering rural villagers the ability to make informed choices about their own menstrual health is key. As of The New Leam’s report in April 2019, the non-profit had reached about 60 Indian villages, providing information about sanitary pads of various designs, longevities, and price points.

While pads are a far more hygienic choice than rags or newspaper, they are not the only option: Back in Manguluru, two German volunteers have initiated a menstrual cup project known as “a period without shame.” In their pilot run, Nanett Bahler and Paulina Falky distributed about 70 menstrual cups free of charge to Indian women, as well as leading workshops on effective use for recipients. The cups, which are made of silicone and emptied around twice per day during one’s period, can be used for up to 10 years, making them a hygienic, eco-friendly, and potentially more affordable option for people of all ages.

Manguluru, where Indian and German activists are working to provide menstrual products. Aleksandr Zykov. CC BY-SA 2.0

Such grassroots efforts have been instrumental in chipping away at stigma among Indians in certain cities and villages, but broader change is unlikely without widespread publicity. One potential avenue for increased awareness is the newly released documentary Period. End of Sentence., which follows rural Indian women in their battle against period stigma. To create the film, Iranian-American director Rayka Zehtabchi visited small villages outside of Delhi to inquire after women’s menstrual health, and shot extensive footage of women who have learned to create their own sanitary products. The diligent pad-makers, many of whom are housewives who have never before held a full-time job, sell their creations to locals in their area, educating women on proper use and convincing shop owners to stock the products. By the end of the time span covered by the documentary, the women had set up a factory and manufactured 18,000 pads, earning economic self-sufficiency for themselves and an Academy Award nomination for Zehtabchi.

The work of these Delhi entrepreneurs, along with that of the AKSRP and Pad Woman Prameela, has made a positive difference for countless people—but, according to Mumbai-based journalist and author Puja Changoiwala, education and access must rise above the grassroots level and reach the legislative in order to create enduring change in attitudes toward menstruation. In a piece for Self, Changoiwala suggests that the Indian government should distribute free pads and launch an “aggressive nation-wide awareness program,” engaging celebrities and the press to address the dire consequences of long-held stigma. For anyone in India with a period, such a moment cannot come soon enough.

TALYA PHELPS hails from the wilds of upstate New York, but dreams of exploring the globe. As former editor-in-chief at the student newspaper of her alma mater, Vassar College, and the daughter of a journalist, she hopes to follow her passion for writing and editing for many years to come. Contact her if you're looking for a spirited debate on the merits of the em dash vs. the hyphen.

A school combines accessible education with environmental responsibility through a creative program.

Photo of plastic waste by John Cameron on Unsplash.

In 2016, Parmita Sarma and Mazin Mukhtar founded Akshar School in Assam, a state in northeast India. Initially, the school struggled to enroll many of the children living in the area. Most families could not afford private school tuition, and relied on the $2.50 per day wage their children could make working in the nearby stone quarries.

In the winter months, many families in Assam burned plastic waste to keep warm, unaware of the health and environmental hazard this created. The fumes would often linger in Akshar’s classrooms, and ended up giving Parmita and Mazin the idea that would transform the school.

Instead of tuition, Akshar began requiring students to bring 25 plastic waste items to school every week. “We wanted to start a free school for all, but stumbled upon this idea after we realised a larger social and ecological problem brewing in this area,” Parmita told Better India.

Through the use of plastic waste as tuition, students who would not have been able to attend the school were able to learn, and the surrounding environment benefitted. Under the new tuition system, the school blossomed, and now enrolls 100 students ages 4 to 15. Before the tuition program was implemented, Akshar had only 20 students.

To compensate for the wages that children could be making working in the mines, Akshar established a tutoring program, where older students can help younger ones with their work in exchange for currency tokens that can be used to purchase snacks, toys, shoes, and clothing. The students can even exchange the tokens for real money to purchase items online. But financial compensation isn’t the only rationalization for the tutoring program. Through teaching, older students are able to develop useful life skills, practicing communication, leadership, and compassion.

Tuition isn’t the only unusual aspect of the school. Parmita told Better India that the goal of the school is to break with traditional curriculum. Students take class in open areas, and grades are divided by level rather than age.

“We realised that education had to be socially, economically and environmentally relevant for these children,” Mazin told Better India. That would mean not only providing an accessible education, but one that would enable children to find jobs after graduation. To this end Akshar offers career focused classes alongside traditional ones, enabling students to gain skills in cosmetology, solar paneling, carpentry, gardening, organic farming, electronics, and more. The school is also willing to adapt to create the best education for its students. Mazin told Better India that when the school noticed a spike in landscaping in Assam, they began to draft plans for a sustainable landscaping course.

Mazin and Parmita’s success with Akshar has inspired them to create more schools that follow the same philosophy. They hope to implement the Akshar model in 5 government schools over the next year, and 100 government schools in the next 5 years.

Emma is an undergraduate student studying English and marketing at Emerson College in Boston. While not writing she explores the nearest museums, reads poetry, and takes classes at her local dance studio. She is passionate about sustainable travel and can't wait to see where life will take her.

Daily life in the Indian holy cities of Rishikesh, Haridwar, and Devprayag. This region lies in the foothills of the Himalayas where the Ganges River descends from the mountains. I visited not knowing what to expect, and I was both awed and saddened by the experience. The beauty of nature and the Hindu ceremonies contrasted with the poverty and suffering on the streets. The people I met had a high-spirited resilience that seemed to stem from surviving and maintaining their devotion through a challenging life.

Holi, known as the Festival of Colors, is a popular Hindu festival celebrated in India and surrounding areas. Colors and water are thrown on each other, amidst loud music and drums to celebrate. Kieran Mellor, the videographer, comments on his work “Since witnessing the insane celebrations of Holi inside Banke Bihari Temple in Vrindavan, I knew that these celebrations deserved their own little film. Hours before the temple doors open, thousands upon thousands of devotees gather to take part in the 20 minute flower and colour throwing celebration of Phoolon Wali Holi. As the doors open, an unstoppable surge begins as the crowd funnels inside and the chanting and applause becomes thunderous. Many people carry offerings which they will bring to the front of the temple to devote to the deities, others pray as they enter through stone archways. For me, however, the most intense part comes when the entire temple unites in raising their hands, and yelling in unison as colours and flowers surround them.”

Home to the legendary, yet treacherous, Chadar Trek, the Zanskar region of Ladakh has earned the reputation of a trekker’s delight.

Stirring images of the Phugtal Monastery, and the river, both in full spate and frozen, of the lush valleys and the Zanskari people have enticed me from the time I was at school and this year, I finally managed to do the trek for myself.

The trek usually begins at Lingshed and culminates in Phugtal, but I undertook it the other way around. In fact, I was able to reduce two days travel time to two hours by chartering a helicopter to my starting off point. It all began at Padum from where we headed to Phugtal and then across the Zanskar through Pishu, Hannmur, ending finally at Lingshed.

The experience was phenomenal. From traversing the most treacherous paths and crossing deep gorges and valleys to witnessing rivers of the most unreal blue and sleeping under the milky way, the entire trek was really something else; the delight of a hot shower at the end of those ten days made it sweeter still. It wasn’t all milk and honey though. Ascending nearly 16,000 feet at some passes and walking at least 20 kilometres a day, the trek tested my wits and guts, making me question why I embarked on this adventure in the first place.

In retrospect though, I can say without a shred of doubt that it was well worth it. Not only did I witness first-hand the glories of a phenomenal terrain, but I also met some wonderful people and experienced inspirational no-waste lifestyles. More than anything else, I learned what I myself am capable of enduring both physically and mentally; that when push comes to shove the human body and mind can surprise us in more ways than one.

HAJRA AHMAD studied photography in Ooty, a small hill town in South India. She became inspired by the darkroom and now specializes in travel and wildlife photography as well as often shooting hotels and interiors. Her photography has enabled her to travel to many new places and her work continues to evolve with each shoot.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON ROAM MAGAZINE

This video portrays the city of Mombasa, which is is a seaport city on the coast of Kenya, along the Indian Ocean. It is the country's oldest and second-largest city, with an estimated population of about 1.5 million people in 2017.

For centuries, Dalits occupied the lowest rung of Indian society. Flickr user The Philosophy of photography - https://www.flickr.com/photos/matteo-gianni/109971376/. CC BY 2.0.

With 1.2 billion citizens India is the second most populous country in the world, and while today’s India is governed by a parliamentary system, for more than three millennia, India’s massive population lived under a rigid caste system that forced many Indians into occupational roles with no hope of advancement. Though modern India has officially done away with castes, the old system’s influence is still felt, particularly among those formerly identified as “untouchables”.

According to Hindu texts, the caste system was brought to India by the creator god Brahma. The top caste was occupied by Brahmins, India’s priests and teachers. Next came Kshatriyas, who were warriors and rulers. Below them, Vaisyas made up the middle class of merchants and traders while Sudras were unskilled workers or peasants. Dalits were “untouchables,” outcasts who existed outside of the caste system entirely and were often relegated to undesirable tasks like street sweeping, toilet cleaning, and disposing of dead animals. A person’s surname identified to which caste they belonged., While one could never hope to ascend to a higher caste in a single lifetime, it was believed that through dedication to one’s Dharma, or caste-specific duty, one could earn a higher position in the next life.

In 1950, the caste system was abolished, creating new opportunities for social mobility and intermingling between India’s various social groups. India even elected a Dalit president, K.R. Narayanan, who served from 1997 until 2002. Tensions remain, however, as Dalits, still identifiable by their surnames, continually find themselves subject to discrimination, harassment, assaults, and rapes. Many attacks go unreported, and local police tend to show leniency to the attackers.

India’s caste system has been likened to South African apartheid or the Jim Crow laws, both of which required many years of legislation and social pressure to affect changes which could be embraced by the general populace—if they were ever fully embraced at all. As India wrestles with its own history of social stratification, the future of its Dalits remains unclear. But it is clear that Dalits, who make up a quarter of India’s population, are an integral part of Indian history, culture, and society, and they won’t be leaving any time soon. Greater equality could be vital to India’s overall health as a country.

JONATHAN ROBINSON is an intern at CATALYST. He is a travel enthusiast always adding new people, places, experiences to his story. He hopes to use writing as a means to connect with others like himself.

With one of the largest kitchens in Asia, the Shri Saibaba temple in Shirdi, India, prepares, cooks and serves quantities of food that are nearly unimaginable. The kitchen dishes out as many as 40,000 meals per day, every day, all year long. It takes 600 people working in two daily shifts to prepare all this food. Yet despite all the effort, meals are free to the public. Why? The temple believes that those who are hungry deserve to be fed, and those who are thirsty deserve to be given a drink.

The supreme court’s decision removed a 150 year old clause created by the British colonial government.

Rainbow flags in Alvula, India. Kandukuru Nagarjun. CC 2.0

Last Thursday the Indian supreme court voted to dismiss section 377 of the Indian Penal Code which made gay sex illegal. The law, labeling gay sex as “against the order of nature” was created in 1860 by the British colonial government and was in existence for 150 years before being struck down last week. While the section was briefly dismissed in 2009, it was reinstated four years later due to appeals filed at the supreme court. It was the supreme court’s decision a few days ago that removed the law once and for all.

The dismissal of the law was due in part to the tireless efforts of many LGBTQ activists who risked reprecutions of up to life imprisonment for publicizing their sexuality in order to petition and protest for the removal of the law. They represent the many gay and trans people who have suffered blackmail, intimidation, and abuse because of the section.

“History owes an apology to members of the community for the delay in ensuring their rights,” Justice Indu Malhotra said in a statement.

The supreme court went further than merely decriminalizing gay sex: as part of the repeal of section 377, gay people in India will finally receive all the protections of their constitution.

The law, called “irrational, indefensible and manifestly arbitrary” but Chief Justice Dipak Misra, was defeated in part because it conflicted with a recent law granting privacy as a constitutional right. It was also largely perceived out of step with modern India. In their decision, the justices referenced the fact that the Indian constitution is not “a collection of mere dead letters”, but a document open to evolving with time and social attitudes.

According to Menaka Guruswamy, one of the main lawyers representing gay petitioners, the court's decision not to discriminate based on sexual orientation has created a “very powerful foundation.” It represents a public acknowledgement that as a gay person, “You are not alone. The court stands with you. The Constitution stands with you. And therefore your country stands with you.”

In excitement over the law it is important to acknowledge that India is not in any way “catching up” to the west in LGBTQ rights. Instead, the removal of this oppressive law is an example of India decolonizing. Many Hindu temples show images of people of the same sex embracing erotically. In the temples of Khajuraho there are depictions of women embracing and men showing their genitals to each other. There are Hindu myths in which men become pregnant and in which transgender people are awarded with special ranks. India Today writes that “In the Valmiki Ramayana, Lord Rama's devotee and companion Hanuman is said to have seen Rakshasa women kissing and embracing other women.”

In response to the law’s framing of homosexuality as unnatural, Anil Bhanot wrote in the Guardian that “the ancient Hindu scriptures describe the homosexual condition to be a biological one, and although the scripture gives guidance to parents on how to avoid procreating a homosexual child, it does not condemn the child as unnatural.”

The removal of the law represents a shift toward a more progressive future while also returning to India’s pre colonial attitudes.

EMMA BRUCE is an undergraduate student studying English and marketing at Emerson College in Boston. While not writing she explores the nearest museums, reads poetry, and takes classes at her local dance studio. She is passionate about sustainable travel and can't wait to see where life will take her.