For more than two decades, through the lens of my camera, I have sought out the hope and beauty woven into the fabric of all life and all peoples, from forest to ocean. In the face of the myriad unrecognized plights and urgent truths of our shared human and planetary condition, these shimmering threads promise change.

Images / Words © Cristina Mittermeier / Words © Kim Frank

National Geographic photographer and co-founder of SeaLegacy, Cristina Mittermeier, releases her new book this month, Amaze, published by teNeues. An intimate collection of over 25 years, Amaze combines impassioned poetic storytelling, indigenous wisdom, and an urgent plea to protect our planet. Amaze takes you on a insightful and hope-filled journey where the human spirit lifts from every page. Here is a glimpse into the book’s luminous world.

Ta’kaiya Blaney, a singer, songwriter, and drummer for her people, the Tla’amin First Nation of British Columbia, is seen in a cedar cape. The youngest speaker at the United Nations Indigenous Forum, she is a fierce advocate of indigenous rights and environmental protection.

AS WITH MANY IMPASSIONED JOURNEYS, MY LIFE AS A CONSERVATIONIST AND ARTIST BEGAN WITH A LESSON.

A lesson that rattles in my soul like a grain of sand in a chambered nautilus shell. Urging me onwards; reminding me why I do this work. Curled deep within this hidden spiral is the unwavering memory of one of the most powerful photographs I never took.

The densely knit Amazon rainforest; home to countless indigenous peoples and the once-mighty Xingú River, now forever tamed.

When I was a young and inexperienced photographer, I was sent on an assignment to a remote corner of the Brazilian Amazon. Flying from town to town, over vast stretches of rainforest, and in increasingly small airplanes, I finally arrived at the Kayapó village of Kendjam; home to one hundred and fifty individuals. My mission was to give a face and a name to the thousands of indigenous people whose lives were soon to be impacted by the construction of the Belo Monte dam.

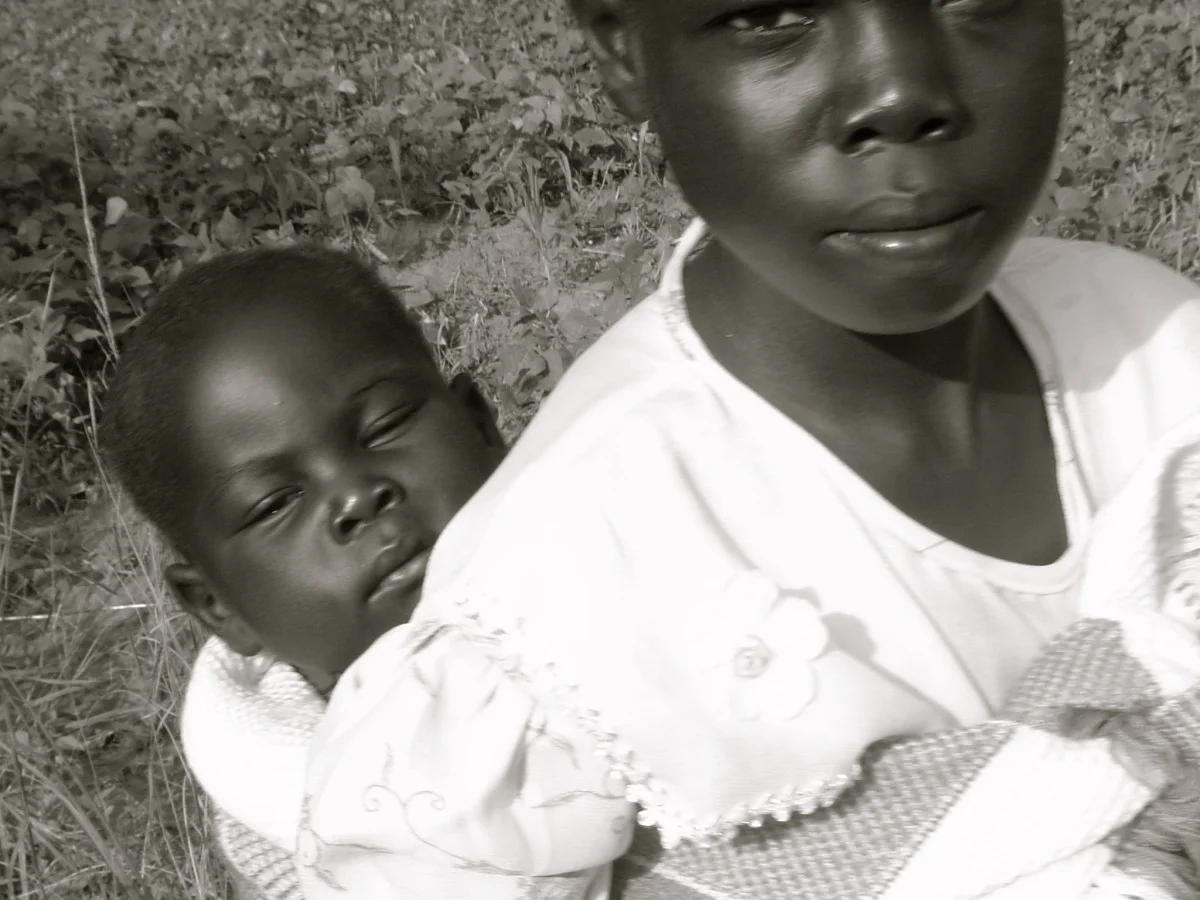

Young Kayapó children will sit or stand patiently for hours, as their mothers paint their bodies with genipap, a dye made from a forest fruit of the same name. Being painted, and painting others, is a very important form of social bonding in these remote Amazonian villages.

Late one afternoon, I saw a group of women coming up from the river; one of them carrying a tiny baby in her arms. It dawned on me that they had just given this newborn his first bath in the river; a vital ritual bath that ties a person’s fate to the fate of the river. And I had missed it. I consoled myself, naively thinking I that could find the mother in the morning and ask her to bring her baby back down to the water, hoping to recreate what I had missed. Tragically, we woke to the news that the infant had not lived through the night. By the time I had figured out what was happening, the women had already buried the tiny body, and I had missed that ritual as well.

Dismayed, I began to wonder if I was up to the challenge of this assignment, wishing the editors had sent a more experienced photographer, when out of the corner of my eye I saw a figure approaching. It was the mother of the baby, walking straight towards me and bawling. Nobody was going near her. As she came closer, I saw that she was cradling a dirty bundle.

In her sorrow, she had dug out the body of her dead child, and was carrying him around. Clutching a machete in her hand, she was hitting her forehead with the blunt edge as she screamed out her sorrow. Her face, her dress, her dead son; all were covered in mud and blood.

I stood there, gripping my camera with frozen fingers; paralyzed.

I could think only of my children back home and how I would feel if a stranger shoved a camera in my face just after I had lost my child. I am ashamed to admit that I did not take any photos.

The Xingú river is intimately woven into the fabric of Kayapó life. This young girl’s eyes speak of a beloved waterway about to be dammed forever, of pride in her people’s traditions, of fear for a future unknown, and of the innocence that every child deserves to live with.

A few months later we learned that the dam had been approved and construction was to begin immediately. I thought about the beautiful, generous people I had met and how their lives would be changed forever.

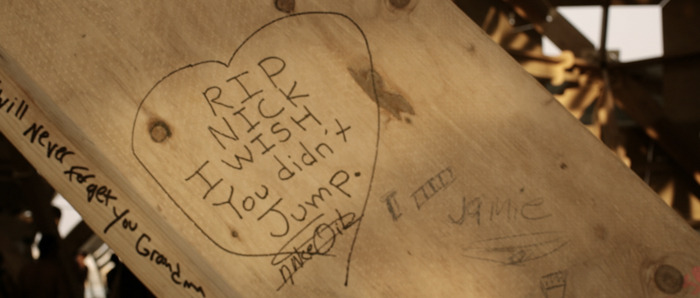

To this day, I am haunted by this question:

Would their fate have been been different if I had dared to do my job and take those difficult photographs? What if my images had been beautiful enough, or dramatic enough, to change the conversation?

The Kayapó people believe that if they are good to the forest and to the river, they will be provided with everything they need to sustain themselves.

I will never know, because that day I lacked the courage to press the shutter: a mistake I never made again. From that moment forwards, I pledged never to hesitate and to make images that matter.

For centuries the Kayapó way of life has been deeply entwined with the rivers that flow through the forest. For me, this image is a powerful symbol of nature’s familial hold on the human spirit, reminding us that nature is so much more than a commodity to exploit.

Over the course of my career I have witnessed photography’s ability to shape perceptions, help societies pause and reflect, and inspire change. Being a photographer allows me to share my deepened understanding of the truth that all things in nature are part of one vast ecosystem.

Unlike people, the Earth’s diverse waterways, wildlife, and forests are intricately woven into the fabric of the whole; not claiming a separate existence. My hope is that my images will inspire a stronger connection with the nature that lies within and around us, as it is infinitely worthy of our deepest respect and care.

In a raw world that seems to bleed everyday with shriveling resources, human tragedy, and environmental ruin. Where every moment with a press of a button or a swipe of a screen, we are assaulted with distressing news, stories and images that threaten our sense of security and dim our lights, we must find ways to remain optimistic.

We must work to remove the physical and metaphorical barriers that block our meaningful connection to one another and to our planet. In my twenty five years documenting remote tribal communities around the world I have learned important lessons from their collective wisdom.

A young girl of the Afar tribe, from Ethiopia. Her people are fiercely proud and independent, having lived forever in the harsh deserts of the Horn of Africa, as semi-nomadic cattle and camel herders.

Spending time with Indigenous peoples has taught me that abundance is not measured in the things that we own, but in the strength of our human spirit, and in the depth of our connection to the natural world.

From the Amazon to the Arctic, these communities nurture an intimate awareness of the web of relationships that have sustained them in harmony with nature, for millennia. I have long thought about how I could share my own interpretation of this intuitive wisdom. Among the Kayapó, the Gitga’at, the Inuit, and the many other Indigenous communities I have photographed, I have witnessed a myriad of common strands — spiritual and physical; past and future. Woven together, they become the exquisite and universal fabric of something that I have come to call “enoughness”.

Made from the feathers of birds of paradise, the Indigenous peoples in the highlands of Papua New Guinea pride themselves on elaborate personal decoration. This woman’s spectacular headdress had been passed down from generation to generation.

My personal true north for navigating the complexities and contradictions of modern life with more planetary integrity, I search for these threads of enoughness: belonging, purpose, sacred ecology, spirituality, and creative expression in the people I meet, and the experiences I have.

I describe and show enoughness within the words and images in the first part of my book, Amaze, and I share an excerpt with you here. It is my hope that enoughness can be recognized as a path to a more fully expressed life, as we seek to entwine these threads more deeply into our own personal tapestry.

I am often asked if I gave gum to these boys from the highlands of Papua New Guinea, but the answer is no. They were at the Mount Hagen Sing-Sing, a festival that celebrated the most culturally-intact tribe, and delighted in surprising me with their bubbles.

We all yearn to belong, whether it be to a people, or to a place.

On the spray-soaked shorelines of the Pacific Northwest, a part of the world that I am now fortunate enough to call home, the Sundance Chief of the Tsleil-Wuatuth First Nation shared with me what belonging means to him. For his people, the land is not something that you own, nor is it a commodity to be bought and sold. Instead, it is something that you belong to.

For over 30,000 years the Tsleil-Waututh First Nation and their ancestors have lived in the region we now call Burrard Inlet.

Rock, tree, river, or hill, crow, bear, or human, all were formed from the same elements by the Ancestors long ago. Their land is alive with relations, no matter the shape that relation may take. When you love, need, and care for the land, in return, the land will love, need, and care for its people. For the Tsleil-Waututh, the land is both family and self.

It is the ultimate expression of belonging.

Wearing his people’s traditional headdress, Will George, of the Tsleil-Waututh First Nation, screams out his frustration at the Canadian government for allowing the expansion of another destructive oil pipeline across his people’s ancestral lands.

Over the years I have observed that irrespective of culture and our place within the world, the path to true fulfillment often lies in finding joy and meaning through purpose. Living a life of purpose may mean intentionally raising your children wholeheartedly as compassionate, courageous citizens, of planet Earth, or it may mean developing your unique skill or talent so that you can contribute to your community. For me, it is the feeling that my passion lines up with what the world needs. Regardless, it is about recognizing your own inner value.

Seeking shelter from the relentless sun, I was invited in by this beautiful Antandroy woman, who was wearing a traditional mask made of powdered bark, a natural mosquito repellent and sunblock. She too was feeling unwell and I was moved by her humble hospitality and grace.

I marvel at how when we treat one another with compassion, and respect the creatures and land we rely on, our sense of personal nourishment grows in direct relationship. The elements that make up enoughness help us cultivate fulfillment from within. Rather than needing or expecting the world to give us something, enoughness naturally inspires us to give back, to others and to the planet. Cultivating a sense of belonging, embracing spirituality, and intentionally finding purpose. Tapping into existing sacred ecologies and embracing our natural gifts for creative expression. This is how we can nurture enoughness, as individuals, and as an intimately connected global community.

In northwestern Yunnan, each village has a sacred forest where the locals believe the gods reside, along with the spirits of their ancestors. People are not allowed to cut down trees, but they can collect fallen branches, mushrooms, and medicinal plants.

Enoughness is the feeling of something central being restored. It is a luminous path to a fully expressed life.

What a joy it has been to find the purposeful focus of living from enoughness in my own life; by looking carefully and listening closely to the lessons shared with me by the people who still live close to the land and who know how to carve a living from the Earth without destroying it.

The embodiment of strength, knowledge, and the rich cultural heritage of her people, who have lived in the rainforests of Brazil for millenia, this Kayapó elder is a leader in her community and a proud keeper of their traditional knowledge.

Eyes on the horizon, Miracle, Virtuous, and Heavenly Kaahanui float with their surfboards, waiting for the next set of waves to roll in. For centuries their ancestors have practiced this art, perfecting their prowess in the water, and nurturing a deep connection with the life-giving grace of the sea. In that moment, soaked in the glittering spray of the vast Pacific Ocean once again, I know for certain that long-lasting change will only come when we feel more connected to the surge of life that is beating on our shores.

Three Hawaiian sisters wait for the waves in Makaha Beach, Oahu.

Over millennia, the tireless swing of the tides has given shape to the continents and character to our coasts; morphed and bent to the will of the sea. Every day, for a few precious hours, the shore belongs to the land. Then under the gravitational spell of the moon, it is once again reclaimed by the waves. To us, however, it never truly belongs.

There is an invisible line between the familiar feeling of our feet on solid ground and the inky abyss, often foreign and fearsome, where creatures with gills, scales, and fins are better suited to survive.

[1] A curious Stellar sea lion in the rich waters of the Salish Sea. [2] Molina Dawson, a young Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw warrior, is occupying the polluting open-net fish farm that was placed in her people’s ancestral territory without their consent.

Though bound to the land, humans have benefited from the riches of the sea since the beginning of time. We should know by now that if our oceans thrive, so do we. Why then, are we collectively failing to nurture and protect the cornerstone of all life on Earth?

As he lifts his eyes to the falling snowflakes, Naimanngitsoq Kristiansen, a traditional Inuit hunter from Greenland, reminds me that nature is a spiritual sanctuary, made all the more hallowed by the first flurry of snow in Spring.

Knowingly or not we have abused the generosity of the sea. Perhaps we have been walking on land for so long, we have forgotten that our very existence depends on a healthy ocean. Every second breath we take comes from the sea; the oceans are the watery lungs of our planet, producing vast amounts of oxygen and absorbing countless tons of carbon dioxide.

One billion people, including many of the world’s poor, rely on fish for their daily protein. The rain and snow that falls over distant mountains, irrigating fields many miles from the shore, originates at sea. Immense ocean currents regulate our planetary climate, maintaining the perfect conditions for our fragile existence. Today, human-induced global warming and exploitation of our environment are threatening to destabilize all of this.

On a three-week long expedition from the southernmost tip of India to Chennai, I stopped in every coastal town to see what the fishermen were bringing in. The women I met told me that the fish are getting smaller and smaller, and many species are disappearing.

HOWEVER, ALL IS NOT LOST. WE STILL HAVE TIME TO NURTURE THE OCEAN’S INCREDIBLE RESILIENCE.

From Mexico to the Pacific Northwest, I have witnessed entire ocean ecosystems spring back to life when local communities are empowered to sustainably manage and restore their waters. Slowly but surely, communities around the world are harnessing the political will necessary to bring our oceans back to health. When we act together, we can inspire great change. This is why I co-founded SeaLegacy with my life partner, Paul Nicklen.

Zah, an artisanal fisherman, harpoons fish in the Abrolhos Reef to feed his family. Because they live in a Marine Protected Extractive Area, fishermen like Zah are committed to complying with fishing regulations and no-take zones, which benefit their local ecosystem.

With a mission to create healthy and abundant oceans for our planet, SeaLegacy is a strong, collective voice of organizations, social media influencers and individuals working together to spark the kind of global conversation that inspires people to act. Through powerful media and art we deliver hope — the kind of hope that empowers and generates solutions. Hope can be a game changer, and hope for our planet is empowering.

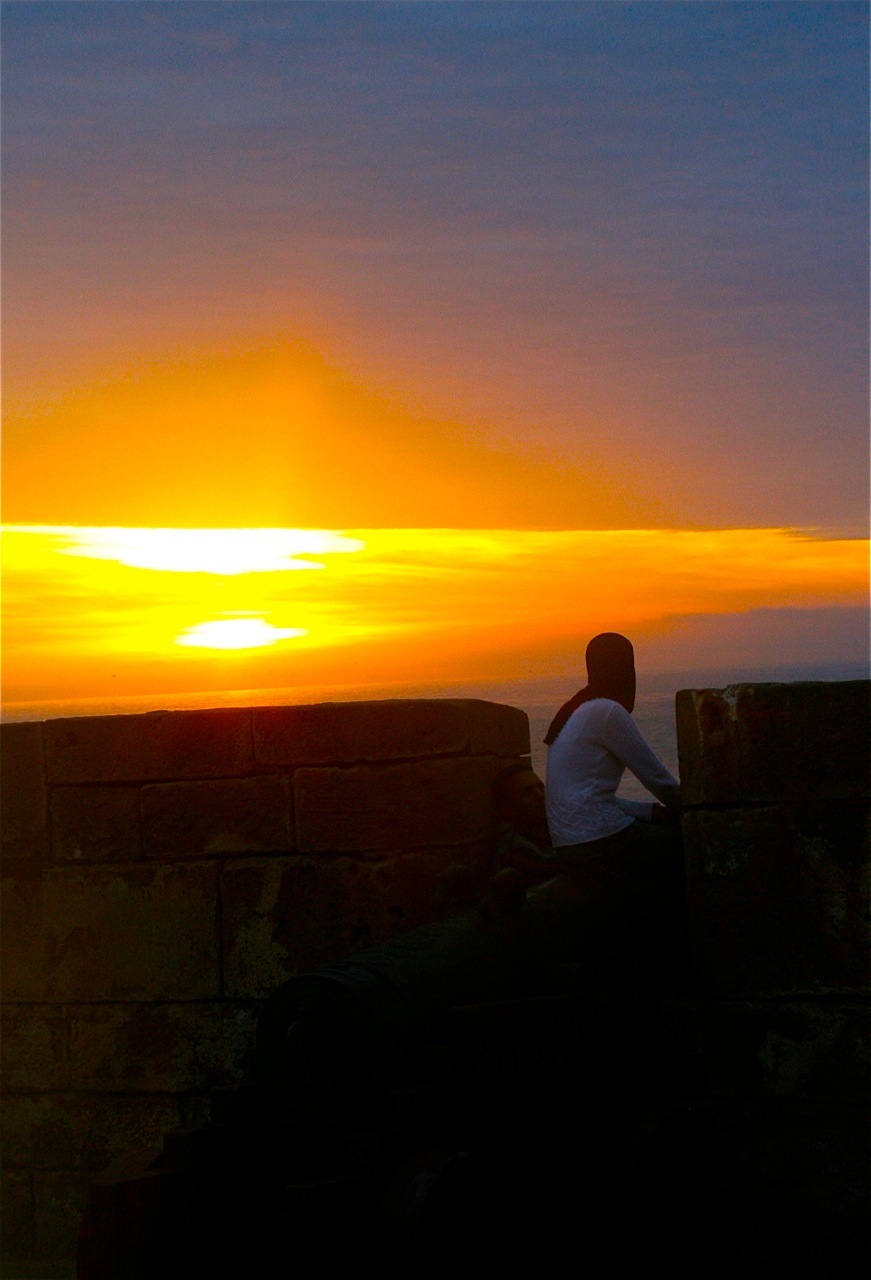

I watched as the sun dipped below the horizon, and the molten gold of sunset saturated the twilight. Just as his ancestors have done for centuries before him, Naimanngitsoq Kristiansen waits patiently for harp seal or walrus at the ice edge.

Extraordinary opportunities exist to restore and thoughtfully develop our oceans in order to protect them and sustain life on this planet.

Our team at SeaLegacy works with an international council of experts to identify projects that are helping to create healthy and abundant oceans. We engage a groundswell social audience of over six million followers with compelling storytelling and invest in community-centered solutions, rallying global support through our massive media network.

Through vibrant digital campaigns, we take on projects such as influencing policy makers to protect whale habitats in the Norwegian fjords, filmmaking to show the critical ecological value of keeping the Antarctic Peninsula wild and free, and partnering with indigenous First Nations communities to ban harmful fish farming in northern Vancouver Island, Canada.

Every day, through our vital work, I experience hope in action. Co-founding SeaLegacy gifts me with the ability to align the rich elements of enoughness with my deep concern for life beneath the thin blue line of our ocean.

From the air we breathe, to the food we eat, to the climate we live in, we all depend on our oceans. Today, they are more important than ever. Healthy oceans absorb vast amounts of carbon from our atmosphere and help reduce the impact of climate change.

On nights when the opalescent moon brings waves crashing against the rocky shoreline of the coast that I call home, I rejoice in the pungent scent of saltwater. The sea is like a forgotten womb from which all life emerged. It is here, at the water’s edge, that my heart beats its loudest.

Perhaps it is the reassuring cadence of the tidal rhythms or the way that the waves roll in from the open ocean with playful, operatic grace, carrying dreams of faraway underwater kingdoms. Or perhaps it is the way that the ocean’s low, sacred rumble rests in my soul, long after the last grain of sand has washed from between my toes.

A shimmering sunset is reflected in these shallow waters, as traditional Vezo fishermen draw up their boats for the night.

As a photographer, I feel an urgency to remind my fellow humans that our destiny is inexorably tied to the fate of the sea. As a scientist, I am motivated by the knowledge that continuing to ignore the failing health of our oceans now, while we ponder the consequences later, is an invitation for disaster.

Combining the two, I am a fierce advocate for our planet and strive every day to make a tangible difference. With hope as a beacon, my dream is that together we can turn the tide and achieve healthy, abundant oceans for all.

Two young Vezo girls, like water nymphs more at home in the ocean than on land, gather fish for their family’s dinner.

CRISTINA MITTERMEIER is a photographer, writer and conservationist documenting the intersection of wild nature and humans. Co-founder at SeaLegacy.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON MAPTIA