In a series of provocative photographs, poor children in India were made to pose in front of fancy tables covered with fake food. A prize-winning Italian photographer, Alessio Mamo, took these pictures in 2011, as part of a project called “Dreaming Food.” After the World Press Photo Foundation shared the photos on Instagram, they sparked a bitter controversy. Many considered them unethical and offensive.

In his apology, Mamo described his desire to show to a Western audience “in a provocative way, about the waste of food.” He was attacked for lacking cultural sensitivity and violating 21st-century photographic ethics.

Despite such risks, as a public law scholar, I am aware that images of suffering are often part of human rights campaigns. And freedom of expression, including visual representation, is protected by a United Nations treaty and many national constitutions.

At the same time, however, I argue for ethical limitations on the right to take pictures.

Moral questions

The controversy around Mamo’s so-called “poverty porn” images is not the first time that such questions have been raised.

The iconic photograph ‘Migrant Mother’ by Dorothea Lange, on display at the Oakland Museum of California. AP Photo/Eric Risberg

One such case was that of the 1936 black-and-white photograph of Florence Owens Thompson that became the iconic image of the “Migrant Mother” during the Depression. Photographer Dorothea Lange took the picture for Resettlement Administration, a New Deal agency tasked with helping poor families relocate. It showed Thompson, with her children, living in poverty.

The family survived on frozen vegetables and birds they hunted. The photo was intended to build support for social welfare policies.

The photo raised some moral questions.

While Lange shot to fame, no one knew the name of the woman. It was only decades later that Thompson was tracked down and agreed to tell her story. As it turned out, Thompson didn’t profit from “Migrant Mother” and continued to work hard to keep her family together. As she said later,

“I didn’t get anything out of it. I wish she hadn’t taken my picture. … She didn’t ask my name. She said she wouldn’t sell the pictures. She said she’d send me a copy. She never did.”

Thompson felt “bitter, angry and alienated,” over the “commodification” of her image, wrote scholars Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites, in their study of powerful images.

Thompson was the poster child for the Depression, and she did take some pride in that. Her photo benefited many. But, as she asked a reporter, “what good’s it doing me?”

What’s the role of a photographer?

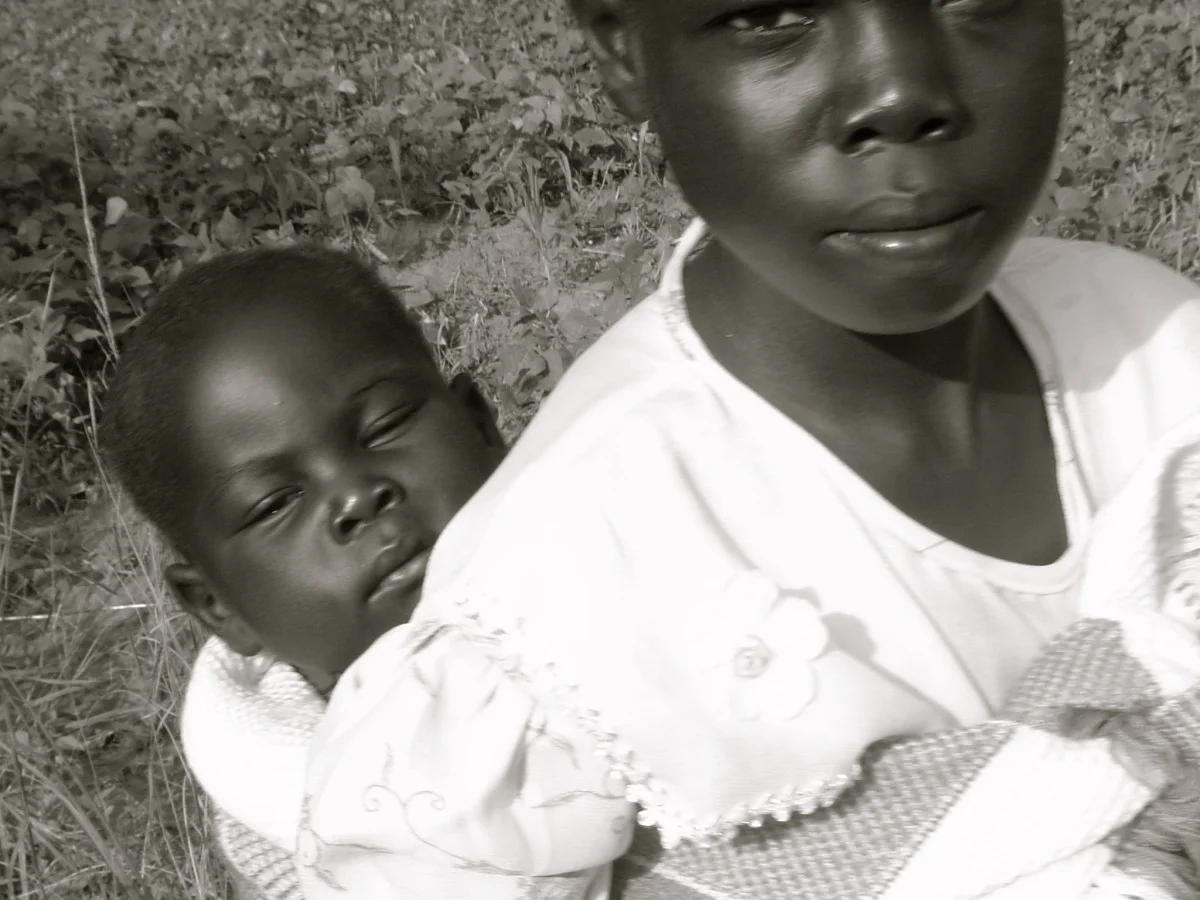

Another striking example is a 1993 photo by South African photographer Kevin Carter showing a young Sudanese girl, with a vulture perched near her. The iconic image captured public attention by focusing on the plight of children during a time of famine.

Kevin Carter’s photo shows a starving girl with a vulture next to her. Cliff

Unlike other images depicting starving children with “flies in the eyes,” this one highlighted the predicament of a vulnerable famine victim, crawling to a food station in Ayod, in South Sudan.

The picture won Carter a Pulitzer Prize in 1994, but also precipitated an avalanche of criticism. Although Carter scared the vulture away, he did not carry the girl to the nearby food station. The fate of the girl remained unknown.

In a critical essay about the image, scholars Arthur and Ruth Kleinman asked: Why did the photographer allow the predatory bird to move so close to the child? Why were her relatives no where to be seen? And, what did the photographer do after he took the picture?

They also went on to write that the Pulitzer Prize was won “because of the misery (and probable death) of a nameless little girl.” Some others called Carter “as much a predator as the vulture.”

Two months after receiving the Pulitzer, in July 1994, Carter took his own life. Apart from his own challenging personal circumstances, his suicide note revealed that he was haunted by the vivid memories of the suffering that he witnessed.

Pictures for charity

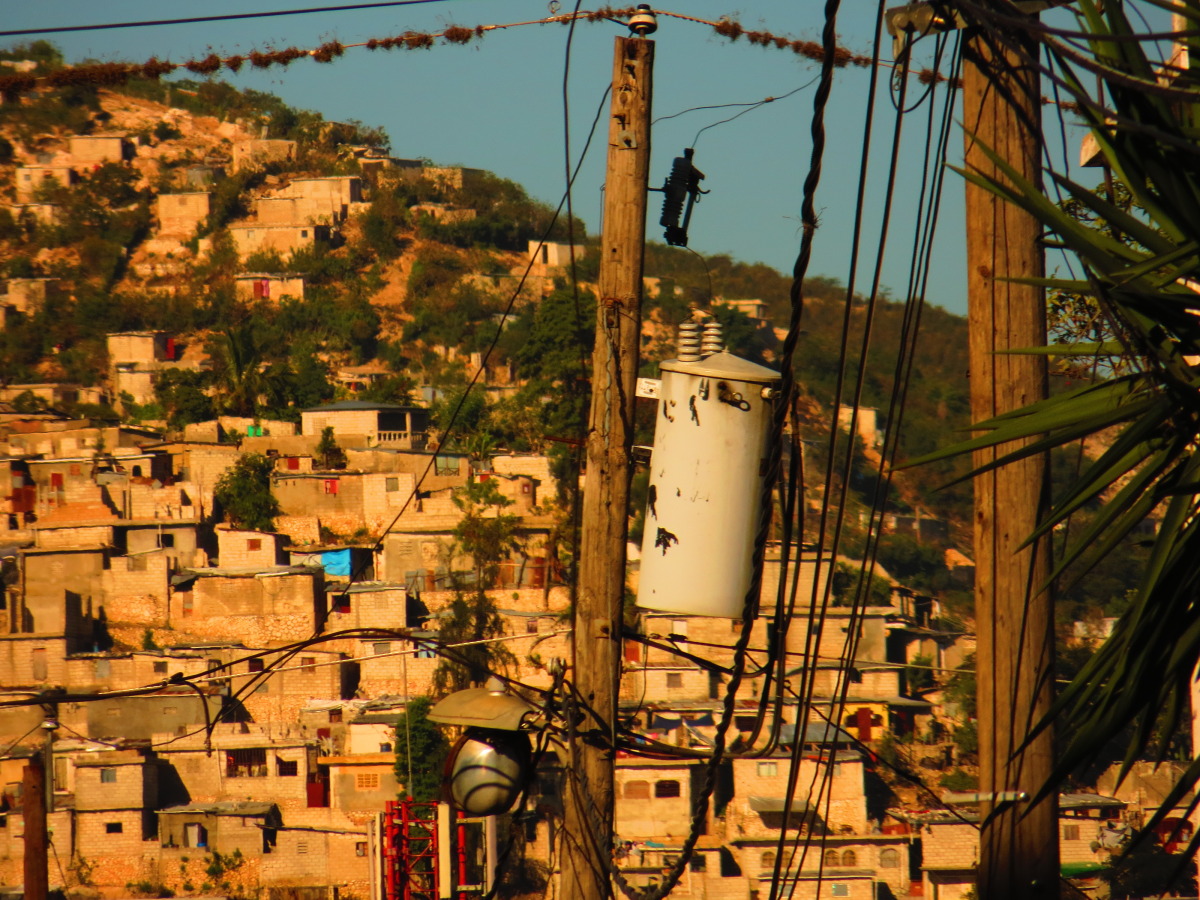

Admittedly, famine, poverty and disasters need attention and action. The challenge for journalists, as scholar David Campbell notes, is to mobilize public reactions before it is too late.

These catastrophes require prompt intervention by government and relief agencies, through, what human rights scholar Thomas Keenan and others call, “mobilizing shame” – a way of exerting pressure on states to act to rescue those in dire circumstances.

Such an effort is often more effective if images are used. As Rakiya Omaar and Alex de Waal, co-directors of African Rights, a new human rights organization based in London, note,

“The most respectable excuse for selectively presenting images of starvation is that this is necessary to elicit our charity.”

The truth is, these images do have an impact. When James Nachtwey, an American photographer, took photos of the famine in Somalia, the world was moved. The Red Cross said public support resulted in what was then its largest operation since WWII. It was much the same with Carter’s image, which helped galvanize aid to Sudan.

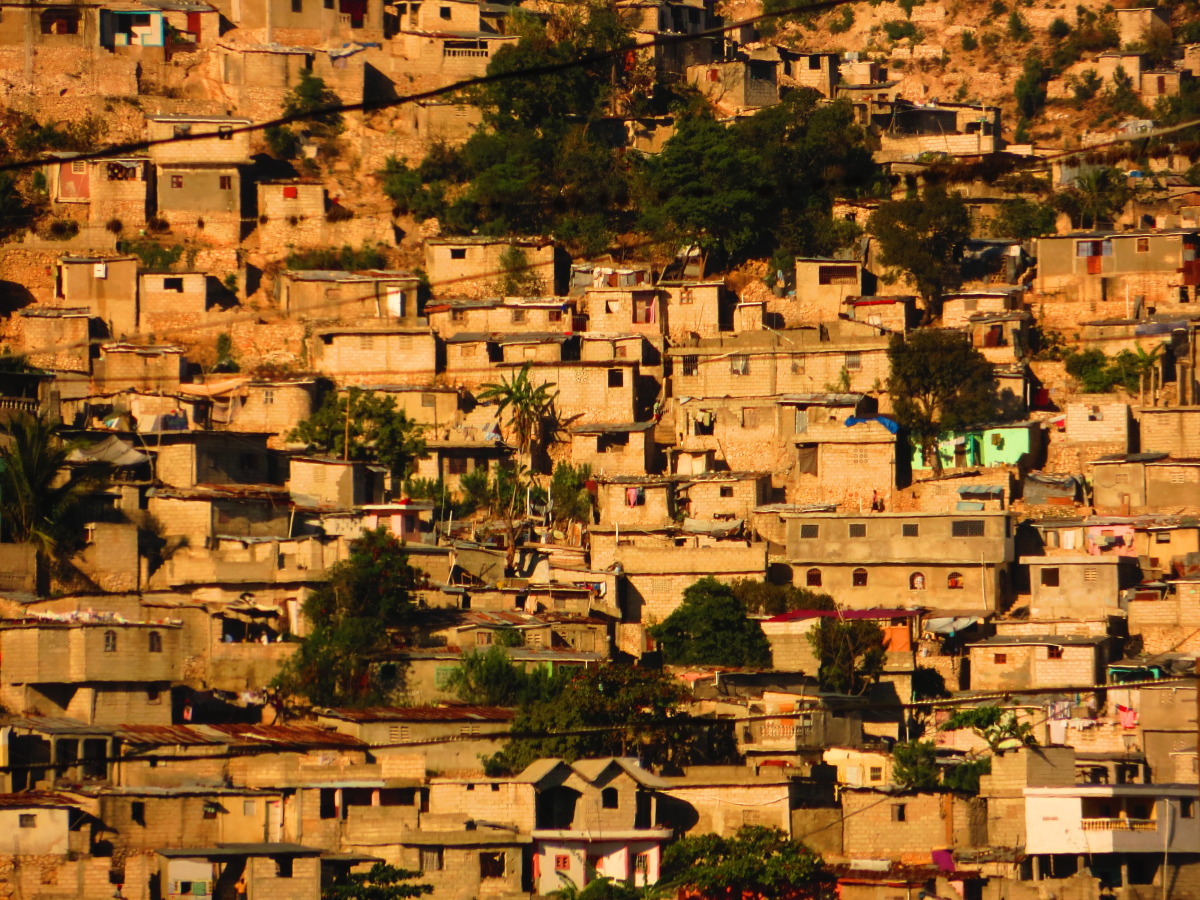

Nonetheless, as Campbell contends, media coverage can reinforce negative stereotypes through an iconography of famine or images of those starving in “remote” places like Africa. His argument is that individuals continue to present people in what the Kleinmans call the “ideologically Western mode.”

In this framing, the individual appears without context, usually alone, and without the ability to act independently.

Changing representations

Greater awareness of the power of images in different contexts has exerted pressure on NGOs and journalists to shift from a “politics of pity” to a “politics of dignity.”

In 2010 Amnesty International issued photo guidelines, regarding rules for images that show suffering. Save the Children also drafted a manual after conducting research on image ethics in various parts of the world.

Explicit rules include not posing subjects, avoiding nudity and consulting subjects about the way they believe the narrative ought to be presented visually. A major concern has been how sometimes the subjects and scene might be manipulated to orchestrate an image.

What this reflects is a desire to show greater sensitivity to the precarious status of some subjects in photographs.

But this is easier said than done. Recognizing that voyeuristic interpretation of distant suffering is offensive does not necessarily mean this practice will cease. The real challenge ultimately is that the ethically problematic images that present “pitiful” victims to the world are often the ones that capture public attention.

Eventually, much rests on the stringent ethical standards that photographers set for themselves. What they do need to remember, is that often, good intentions do not justify the use of questionable images of suffering.

ALISON DUNDES RENTEIN is a Professor of Political Science, Anthropology, Public Policy and Law at the University of Southern California – Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION