Brazil, the last South American country to abolish slavery in the late 1800s, struggles to uplift their nation’s Black lives. Through pay gaps, urban designs, government representation and policing, Brazil’s society threatens the Black community.

A protester on the streets in Brazil. Michelle Guimarães.

Over the course of 300 years, approximately four million Africans were taken to Brazil as slaves. Today, Brazil’s racial demographics are 47.7 percent white, 43.1 percent multiracial and 7.6 percent Black. The average income for white Brazilians is almost double that of the average income for Black or multiracial Brazilians, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Also, 78.5 percent of people in Brazil who are receiving the lowest rate of income (equivalent to $5.50 U.S. dollars per day) are Black or multiracial people.

This May, Black Lives Matter protests filled the streets of Rio de Janeiro, Sao Paulo and Brasília after 28 people died during a police raid. Human rights activists said that the officers killed people who wanted to surrender and posed no threat. The raid took place in Rio de Janeiro, where heavily armed officers with helicopters and vehicles went into Jacarezinho, a poor neighborhood. Thousands of residents were subject to nine hours of terror.

Organizers said that 7,000 people took to the streets in Sao Paulo. Protesters painted the Brazilian flag with red paint and held up a school uniform stained with blood. In Rio de Janeiro, protestors chanted, “Don’t kill me, kill racism.”

As Brazilian author and activist Djamila Ribeiro said, “The Brazilian state didn't create any kind of public policy to integrate Black people in society," and that "although we didn't have a legal apartheid like the U.S. or South Africa, society is very segregated—institutionally and structurally."

In 2019, the police killed 6,357 people in Brazil, which is one of the highest rates of police killings in the world—and almost 80 percent of the victims were Black.

During COVID-19, Black Brazilians were more likely than other racial groups to report COVID-19 symptoms, and more likely to die in the hospital. Experts attributed this disparity to high rates of informal employment among Black people, preventing them from the ability to work from home, and a higher prevalence of pre-existing conditions. Specifically, in 2019, Black Brazilians already accounted for the majority of unemployed workers (64.2%); therefore, they already lacked economic support even before the pandemic.

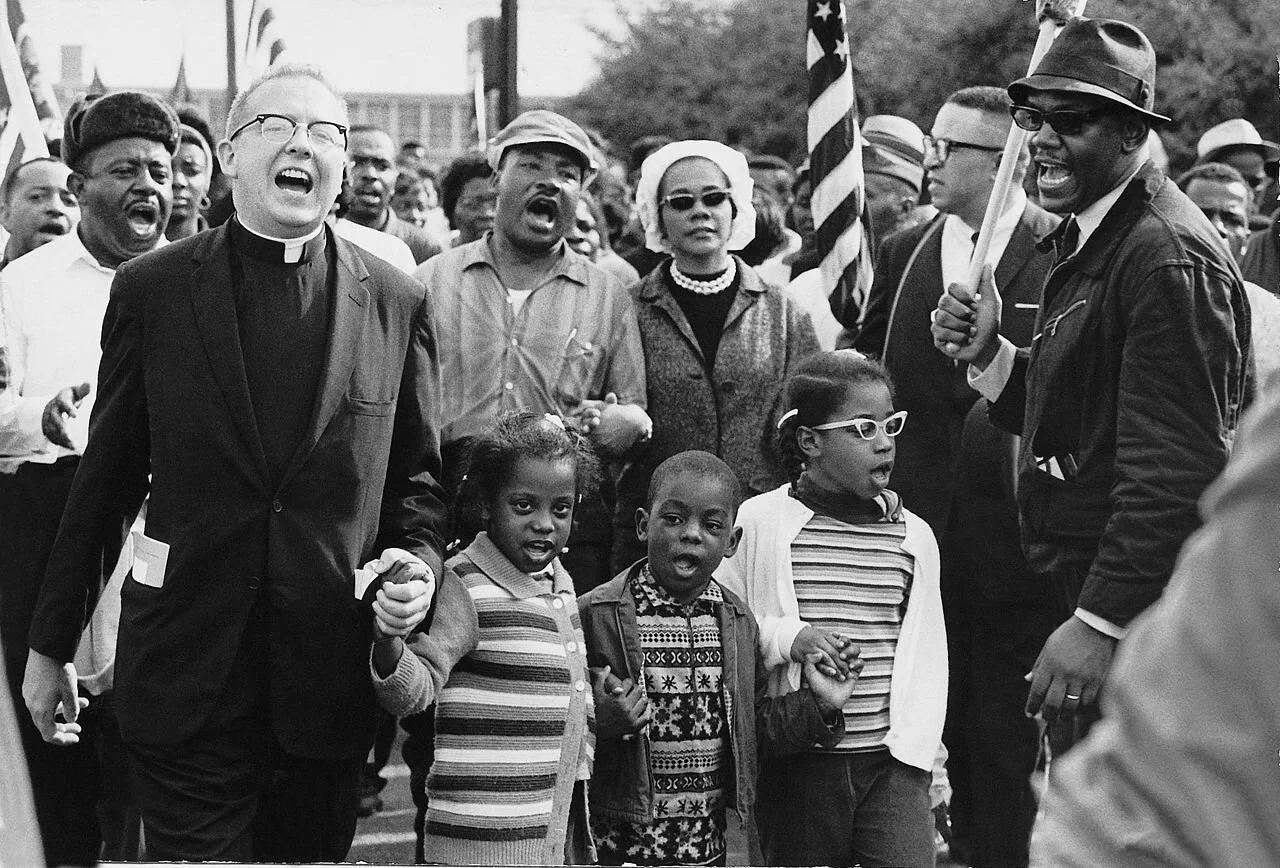

An artist’s photoshoot with Brazil flag covering their bodies. Eriscolors.

Only a quarter of federal deputies in the lower chamber of Brazil’s Congress and a third of managerial roles in companies were Black people, according to the IBGE statistics from 2019.

Brazil’s President, Jair Bolsonaro, said during his campaign in 2018 that descendants of people who were enslaved were “good for nothing, not even to procreate,” while using the slogan “my color is Brazil.”

Keisha-Khan Y. Perry, a professor at the University of Texas, conducted an ethnographic study looking at how Black women in Gamboa de Baixo—a city culturally and historically tied to Black Brazilians—are leading the community towards social activism against racist politics. Specifically, these racist policies include political urban revitalization programs that push out Black and poor people. Perry said that these policies are a political tactic continually utilized in Brazilian cities.

However, recently in May, Milton Barbosa, one of the founders of the most notable Black civil rights organization in Brazil, Unified Black Movement, said, “There’s been an increase in awareness nationally… We still have to fight, but there have been important changes.”

Kyla Denisevich

Kyla is an upcoming senior at Boston University, and is majoring in Journalism with a minor in Anthropology. She writes articles for the Daily Free Press at BU and a local paper in Malden, Massachusetts called Urban Media Arts. Pursuing journalism is her passion, and she aims to highlight stories from people of all walks of life to encourage productive, educated conversation. In the future, Kyla hopes to create well researched multimedia stories which emphasize under-recognized narratives.