Earlier this year, Black Panther premiered in theaters around the world. The latest in a string of comic book-themed films turned out to be more of a cultural event than a mere movie. Black Panther broke records in the United States, as well as Great Britain, North and South Korea, and East and West Africa, dispelling the long-held Hollywood myth that “black films don’t travel.” Though fictional, the film struck a chord with audiences, as it featured a predominantly black cast and did not put them into the stereotypical roles often lamented by moviegoers. The film, however, was not as successful in Mainland China. Despite the fact that China is a major trading partner with the African continent, many Chinese moviegoers bristled at the idea of seeing Africans up close.

Chadwick Boseman, star of the movie Black Panther, appearing at Comic-Con in San Diego. Gaga Skidmore. CC BY SA-2.0

China was relatively closed to foreign trade until Deng Xiaoping's economic reform in 1978. Because of this, interactions with non-Chinese people are still a relatively new phenomenon. There is also a traditional standard in China that equates lighter skin with a comfortable, indoor lifestyle, and darker skin with peasantry, having to labor in fields under the hot sun. This combined with exposure to western media creates an environment that can be less than hospitable to blacks. Last year, an exhibit at the Hubei Provincial Museum in Wuhan titled, “This is Africa”, featured a portrait of a young African boy placed next to the portrait of a monkey. The exhibit was visited by over 100,000 people before criticism from the African community prompted museum officials to dismantle it, and the museum curator to take responsibility for the presentation. In February of this year, the same month Black Panther premiered, China’s Central China Television (CCTV) network came under fire when it aired a skit featuring a Chinese actor in blackface. Beijing issued a statement saying it was opposed to racism of any kind, but did not apologize for the skit.

Western nations are by no means immune to racial prejudice. While the Civil Rights movement of the 1960’s attempted to resolve many of the racial schisms that split the United States, lingering prejudices remain in various parts of the country. In recent years, proponents of racism have become more desperate, and less discreet. In January, the president of the United States allegedly referred to El Salvador, Haiti, and various African nations as “shithole countries,” seemingly forgetting his role as chief diplomat. Perceptions of Africa, and by extension those of African descent, are still slanted by the media, and media still accounts for much of the world’s education. This creates a quandary for those who have to live day-to-day under the banner of these stereotypes.

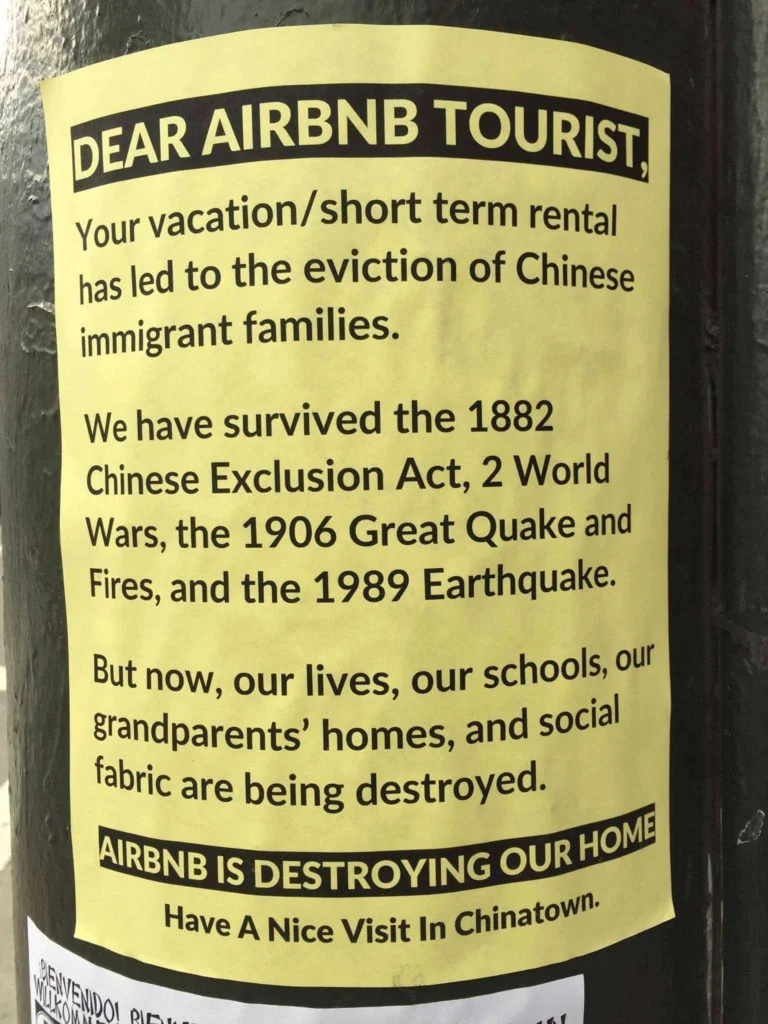

The CCTV building in Beijing. Verdgris. CC BY SA-3.0

There are some things that we believe because it serves us to believe them. Racism today is more than mere ideology. Like sexism, racism has evolved into a cultural standard, feeding into a lifestyle standard that is enjoyed, or not enjoyed, by millions of people around the world. As we begin to tinker with the idea racism, we also tinker with the standards it creates in our societies-some people are bound to get upset. At the same time, this tinkering opens new possibilities for growth, for all the parties it applies to. It refutes old characterizations of people and cultures and encourages us to make connections that we may not have considered before. All change involves a degree of pain and uncertainty, but we can only move forward, confident that the benefits of our efforts will justify the challenges.

JONATHAN ROBINSON is an intern at CATALYST. He is a travel enthusiast always adding new people, places, experiences to his story. He hopes to use writing as a means to connect with others like himself.