Arvīds Barānovs, award winning photographer and head of Eaglewood Pictures, explores Manaslu, a mountain within the Nepalese Himalayas. Manaslu, at 8,163 meters (26,781 feet), is the eighth highest mountain in the world. The mountain stands proudly over Budhi Gandaki valley. At the peak of the mountain, one can gaze upon the adjacent Annapurna mountain range and Tibetan plateau. As one climbs the mountain, they will encounter many small tea houses along the way. Climbers often stop there to have a cup of tea and eat dal bhat, a staple dish of rice and lentils. Manaslu is inhabited by the Tsum and Nubri peoples, whose ways of life are rooted in Buddhism and Tibetan culture. The local people live traditionally and farm barley, maize and oats, in addition to cultivating nuts and fruits.

Sandboarding: The Art of Surfing Sand Around the World

Requiring nothing but a board and steady nerves, sandboarding has become a popular new solo-extreme sport. Small and large competitions occur all over the world as the sport gains popularity.

A man sandboarding in Egypt. Surfing The Nations. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Sandboarding has gained popularity as an extreme solo sport, with competitions held at dunes around the world. The sport is perfect for adventurous athletes and travelers interested in seeing new places and seeking adrenaline-fueled fun, as it can be done anywhere with expansive sand dunes and the right equipment.

The sport itself is logistically simple: riders climb to the top of a sand dune and get on their board. Then, by jumping closer to the downward slope of the dune, pivoting to have their front foot ahead of them and leaning forward, the board will start to move and pick up speed as it makes its way down the slope—similar to snowboarding. Professionals will throw tricks like jumps and spins which have flooded YouTube over the years, and sandboarding courses have even installed bars and pipes for riders to test out, just like a skateboarder or snowboarder would find at parks or slopes.

Surfer Today describes sandboarding as “a blend between surfing, skateboarding and snowboarding.” Typically, sand boards are almost identical to snowboards, yet they tend to be lighter and either include no foot holdings or two straps for each of the rider’s feet with a latch that locks you to the board. No uniform is required unless you are competing professionally, and even then, experts and riders wear casual uniforms during competitions.

Pro-sandboarder Josh Tenge at Sand Master Park. OCVA. CC BY-ND 2.0.

Sandboarding is also an accessible sport that can be done on a range of levels from beginner to expert. At the beginner and intermediate levels, the extreme sport becomes more of a daring passtime. Perfect for summer conditions due to the dryness of the sand, recreational sandboarding is done all around the United States and in other parts of the globe. In the United States, perfect sandboarding conditions can be found in places like Utah’s Coral Pink Sand Dunes Park, Sand Master Park in Oregon, Monahans Sandhills State Park in Texas and the Kelso Dunes in California. There are more great national parks and dunes spread across the United States that perfectly cater to sandboarding conditions, and finding a location nearest to you can be easily done with a simple search on the internet; lists on the best locations to sandboard are scattered across the web because of how popular the activity is.

Additionally, there are amazing places to sandboard across the globe that are perfect for a day trip to some of the world’s most famous dunes and deserts. South America is immensely popular for sandboarding—the World Cup is typically hosted here because of the massive dunes and numerous locations to be found in the continent. Some examples can be found in Peru, at both Cerro Blanco and Huacachina, while other South American spots ideal for the sport are located in Concon, Chile. Towards the Middle East and Africa, other famous deserts and dunes that are great for sandboarding include the Great Sand Sea in Egypt, the Namib Desert in South Africa and the Moroccan Sahara, known for its vast expanse of sandy hills.

The Great Sand Sea in Egypt. Virtualwayfarer. CC BY-NC 2.0.

Most parks do not make visitors pay to use the sand dunes, but occasionally visitors will have to pay an entrance fee—especially if the dunes they wish to ride are located in a national park. If participants wish to take lessons, the prices of those are somewhere between $50 for an individual lesson and $160 for a group lesson with six people that lasts for a few hours at the Sand Master Park in Oregon and may fluctuate depending on where in the world you are trying to board. Rentals are also available at certain locations, like Sand Master Park, and boards costing around $10 to rent for 24 hours. Additional costs can be applied if users wish to rent helmets and other protective gear.

Many people find that the sport just takes practice. The beauty of sandboarding is that it is less risky to try as a beginner because the conditions are better for falling off your board or slipping on your way down the dunes when compared to icy conditions of snowboarding or the hard concrete used for skateboarding.

It is also worth noting that some places require participants to provide their own board; not all locations will have a shop where those looking to sandboard can rent the equipment. Boards for sale online range from anywhere between $150-400, but it depends on brand and size. Cheaper boards can be found on sites like Amazon for anywhere between $40 to $80 if people are not looking to invest in the sport too heavily.

Some slopes even end with a splash in a pond or lake; riders will descend dunes to find a ramp at the bottom which launches them into refreshing, cool water. This is exemplified in Huacachina, Peru, where the dunes feed right into a pond at the center of the village. Huacachina is also listed commonly as one of the best places to sandboard in the world and was the host of the Sandboarding World Cup in 2019.

Dune that feeds to water at Huacachina. Flexbox. CC BY 2.0.

More advanced riders who wish to compete at higher levels have a multitude of competitions to choose from around the globe. Alongside the Sandboarding World Cup, which changes locations frequently, other competitive events include Sand Spirit in Germany, the Pan-American Sandboarding Challenge in Brazil, the Sand Master Jam in Oregon and the Sand Sports Super Show in California. Participants compete for titles and merchandise, all fighting to become champions in this extreme sport.

Sandboarding is a great activity to get adrenaline pumping, explore new areas of the world, and to remain active during travel. . For those looking to ride the craziest, most intense dunes in the world, Peru, Egypt, Japan and a plethora of other locations provide not only a fulfilling trip but host the correct conditions for riding. Perfect for both adventure and travel, the sport encourages riders to seek the most daunting dunes in the world and conquer them.

Ava Mamary

Ava is an undergraduate student at the University of Illinois, double majoring in English and Communications. At school, she Web Writes about music for a student-run radio station. She is also an avid backpacker, which is where her passion for travel and the outdoors comes from. She is very passionate about social justice issues, specifically those involving women’s rights, and is excited to write content about social action across the globe.

Before the Sex Pistols, There Was Peruvian Punk Rock

Western punk groups have taken credit for starting the punk movement, but a small group in 1960s Peru would say otherwise.

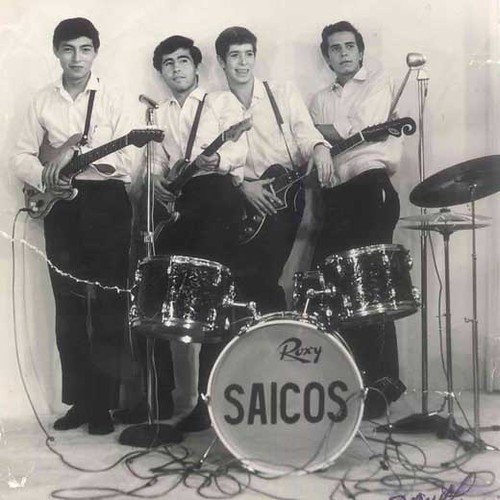

Peruvian punk band Los Saicos. TravelingMan. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Punk music has been used for decades as a means to express discontent about numerous topics, including politics and controversial events. But where does the genre come from? While it is easy to claim Western influences, like the Sex Pistols and The Clash to be the forefathers of the punk scene, the Peruvian rock band Los Saicos, formed in 1964, is a strong contender for the position of “Originators of Punk.”

In order to make comparisons between Los Saicos and Western punk bands, a definition of punk music is in order. Punk music consists of fast beats and often aggressive lyrics that seek to critique certain ideas or systems of power. A recent academic article discusses how the lyrics to the Sex Pistol’s “Anarchy in the U.K.” were a critique of the U.K.’s foreign policy in Ireland, a period known as The Troubles. The Los Saicos song “Demolición” lacks a specific reference to Peruvian politics at the time, but clearly expresses discontent with government infrastructure.

The members of Los Saicos were likely influenced by the political turmoil within Peru during their upbringing. Guitarist and vocalist Erwin Flores and drummer Francisco Guevara had just graduated high school and were grappling with unprecedented political strife, drastically affecting how they prosper as adults. The group was established in 1964, with “Demolición” being one of the country’s biggest songs that year. Amidst massive inflation under President Fernando Terry’s land redistribution policy, economic hardship increased for Peruvians. The lyrics are representative of a future that was promised to them with Terry’s liberal redistribution policies, but one that ultimately drowned with the Peruvian sol’s value. ‘Demolición’ expresses hatred at the government for promising a future and delivering inflation.

Los Saicos broke up in 1966, but its influence was picked up by garage rockers throughout Peru and abroad in the U.K. The punk genre’s grungy and generally angsty music did not necessarily originate from the members of Los Saicos, but they were critical in the genre’s explosion in popularity, especially in areas where there was a discontent with state functions.

“Nobody invented the wheel, we were obviously building off of what others have done,” said Flores in an interview.

The band’s desire to express themselves within a country in turmoil ranges across languages and generations, effectively changing how the music scene functioned as ‘angry’ music started becoming mainstream and profitable.

Clayton Young

Clayton is an aspiring photojournalist with a Bachelor's in Liberal Studies with a minor in History from Indiana University - Bloomington. In his free time, he enjoys hikes, movies, and catching up on the news. He has written extensively on many topics including Japanese incarceration in America during World War II, the history of violence, and anarchist theory.

The Surprising Popularity of Rock Climbing in Slovenia

Slovenia, a Central European country, holds a lesser-known secret: its rock climbing. Not only does Slovenia have many beautiful natural climbing sites, but it also has world-renowned rock gyms and some of the most acclaimed rock climbers in the world.

People climbing Mount Triglav in Slovenia. Derbeth. CC BY 2.0.

Formerly part of Yugoslavia, Slovenia can often be reduced down to its political turmoil. However, this Slavic country is incredibly mountainous and hilly, providing the perfect terrain for rock climbers of all skill levels. Slovenia has produced numerous renowned climbers and built a culture around the sport.

The most well-known Slovenian rock climber would have to be Janja Garnbret, who became the first woman to win gold in sport climbing at the Tokyo 2020 Olympics—the first year that sport climbing was featured at the Olympic games at all. While many people may find rock climbing intriguing and even do it in their free time, it wasn’t well known as a competitive sport until it became an Olympic event. However, competitive rock climbing has a large community, and a major facet of that community is in Slovenia, Garnbret’s home country. For example, Garnbret also placed first in the International Federation of Sport Climbing World Cup in September of 2021, which happened to be hosted in Kranj, Slovenia.

Garnbret follows in the footsteps of years of successful Slovenian women climbers, such as Martina Cufar, who made it on the podium at sixteen different world cup events between 1997 and 2002. Slovenia’s climbing history—specifically when it comes to women—goes back to the early 20th century with Pavla Jesih and Dana Kuraltova, two Slovenian women who climbed the famous Mount Triglav in 1925.

Slovenia’s rock climbing success isn’t by chance. An obvious source of the country’s enthusiasm for the sport is its spectacular mountains such as Mount Triglav. But the success of the Slovenian National Team today can also be attributed to how small the country is and thus how close knit the coaches and the team members are able to be. For example, Slovenian National Team coach Luke Fonda owns Plus Climbing gym in Koper, Slovenia, a gym which the team often practices at.

Climber in Koper, Slovenia. David Glanzer. CC BY 2.0.

In addition to Plus Climbing, rock gyms are plentiful in Slovenia, especially when compared to the country’s size. Some of the most famous gyms are First Ascent in Kranj and The Climbing Ranch in Vrbnje, which serious, competitive climbers from around the world strive to visit. In terms of Slovenia’s natural climbing sites, the country boasts stunning mountains such as Mount Triglav, Mount Viševnik and Mount Prisojnik. The mountains in Slovenia range from beginner to advanced level climbing, with Mount Triglav and Mount Viševnik being doable hikes for most travelers. Mount Prisojnik is known to have a range of trails and climbs—some good for beginners, and others that will be engaging for experienced climbers. Ultimately, Slovenia is a great option for an off-the-beaten-path visit in general, but is especially perfect for those interested in rock climbing, given its rich history and multitude of climbing sites.

RELATED CONTENT:

Ljubljana: The Green City of Slovenia

VIDE: In the Slovenian Alps, an Island on an Emerald Lake Beckons

PHOTO ESSAY: Getting Lost in Slovenia

Calliana Leff

Calliana is currently an undergraduate student at Boston University majoring in English and minoring in psychology. She is passionate about sustainability and traveling in an ethical and respectful way. She hopes to continue her writing career and see more of the world after she graduates.

5 Captivating Silk Road Sites to Visit in Central Asia

Stretching from China and the Far East to Europe and the Middle East, the Silk Road was once the world’s most important trade route.

Read MoreTurning Menaces Into Meals: 5 Invasive Species You Can Eat

Invasive species threaten naturally occurring ecosystems. However, locals and travelers are now being encouraged to eat these organisms, a practice allowing for sustainable eating and providing opportunities for adventurous dining.

A King Lionfish. Niklas FliNdt. CC BY-SA 2.0.

By definition, invasive species are organisms that cause harm to environments they don’t originate from. When a new species is introduced to a naturally occurring ecosystem, they disrupt the balance of the environment and harm the pre-existing organisms in the area. Across the globe, invasive species wreak havoc on struggling ecosystems, but many people have found a possible solution to this environmental issue. In turning their most invasive organisms into food that locals and travelers can eat, countries around the world are creating opportunities for sustainable and adventurous eating, eliminating massive environmental threats along the way.

Eating sustainably is the practice of consuming food and drink that are good for both the consumer and the environment. In eating invasive species, locals and travelers are playing a part in removing harmful organisms in the places they live or visit. To become a sustainable and adventurous traveler, try eating any of these five invasive species on your next trip.

1. Kelp - Alaska

Barnacle Foods pickled kelp. Josefine S. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Invasive species aren’t just animals, they’re plants too. And kelp is one of the most invasive plants in the world; the Global Invasive Species Database (GISD) lists kelp among the top 100 worst invasive species around the globe. It originated in Japan and China but has since traveled through the waters of the Pacific where it now creates major problems for Alaskan marine life. However, a company called Barnacle Foods has created a way to harvest and consume this terrorizing plant: by pickling it.

Stationed in Southeast Alaska, Barnacle Foods is dedicated to harvesting kelp from the water and pickling it.. Set on remaining in Alaska, travelers can only visit their location by boat or plane, but Barnacle Food has made their product available online as well. In turning this invasive species into a beloved snack and by providing multiple recipes on their website for the pickled kelp’s usage, this food has become a great way to eat sustainably for the benefit of Alaskan marine life. It has also become a media sensation, the company gaining over 24,000 followers on Instagram and having been featured by magazines like the Specialty Food Association.

2. Wild Boar - Spain

Although wild boar are found commonly across Europe and the United States and have been flagged as invasive in both continents, they are a true pestilence in Spain. Spanish cities have declared war on these animals, which breed rapidly, disrupt traffic in cities and have become local hunter’s number one target. Additionally, wild boar love to dig up black truffles, and as a leader in black truffle trade, Spain is looking for any way to rid themselves of the species.

Wild boar is said to taste like a cross between beef and pork. In Spain, it is most popularly prepared by the shank or as a stew and typically slow cooked like pork to give the meat a tender, juicy flavor. A great meal for hungry travelers, wild boar is also a great way to eat sustainably on the road and help Spain fight against the pigs that have disrupted their trade and cities.

3. Lionfish - The Mediterranean

Lionfish ceviche served with bread. Leo Roza. CC BY 2.0.

Lionfish have completely overtaken the natural ecosystems in the Mediterranean Sea, but the countries that surround the affected water have started preparing and serving the fish in a multitude of ways. Although poisonous when alive, the lionfish becomes edible when killed, and the Mediterranean region has integrated the species into its culture of fresh, vibrant cuisine.

Becoming a staple in many countries around the Mediterranean Sea, lionfish can be prepared just like all other fish; you can fry it, bake it, pan sear it and even serve it raw. The most popular way travelers will find it served in the Mediterranean is as ceviche. Described as extremely buttery and tender, Lionfish are a menace in the ocean but a treat on the plate of any traveler.

This fish can be found at most restaurants near the Mediterranean Sea. ILionfish is served in the south of France, Italy, Greece, Tunisia, Libya and Spain.

4. Brown Hare - Ireland

Jugged Hare. Kent Wang. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Introduced to Ireland in the mid-1800s, the brown hare, also known as the European hare, has threatened the Irish hare population for decades now. The overpopulation of the brown hare is stealing resources away from Irish hare and herbivores in the country, posing a threat to the ecological integrity of the land. Hunters are allowed to take down hares during the winter months, starting in September and ending in February, and the brown hare has become a major target.

Celtic myth considered it unlawful to eat hares, but modern times have called for different measures. The Irish Examiner says it's time for rabbit to become a part of more Irish menus due to the overpopulation and invasion of the species. Luckily, a dish that originated in France has become more widespread as the brown hare has infiltrated different parts of the globe. Civet of Hare, also known as jugged hare, has become a popular dish in Ireland and the UK—where the hare is also an invasive species in many parts. The dish is made by stewing the entire brown hare in a jug or container with a variety of vegetables and red wine, making the meat so tender it falls right off the bone. This is the perfect dish to warm you up during travel to Ireland, which is notorious for their abundant rainfall and moist climate.

5. Japanese Knotweed - Everywhere but Antarctica

Knotweed ready to be cooked. K_Hargrav. CC BY 2.0.

Last on the list but certainly not least, Japanese knotweed is an invasive plant that is quite literally everywhere on the map. It is said to be found in every part of the globe except Antarctica. Growing at unbelievable rates and heights, it makes it difficult for animals in surrounding areas to walk through its dense brush and feed on other plants. It also blocks sunlight for plants lower to the ground, subsequently killing them.

However, knotweed is edible and an extremely versatile ingredient. The most popular way knotweed is eaten is when it is sauteed like spinach or other leafy greens. It can also be pickled, like kelp, or grilled and roasted in the same way asparagus would be. Bon Appitite published an article on how chefs from all over are using Japanese knotweed as an ingredient in new recipes and where travelers can try them.

Ava Mamary

Ava is an undergraduate student at the University of Illinois, double majoring in English and Communications. At school, she Web Writes about music for a student-run radio station. She is also an avid backpacker, which is where her passion for travel and the outdoors comes from. She is very passionate about social justice issues, specifically those involving women’s rights, and is excited to write content about social action across the globe.

In the Czech Countryside, a City Eaten Alive by Its Own Beauty

Since the fall of communism, Český Krumlov has transformed from relic to hotspot—but has it lost its authentic appeal along the way?

The Czech capital of Prague is known the world over for its storybook beauty, manifesting most dramatically in the towering gothic facade of the St. Vitus Cathedral and the sprawling tableau of red rooftops visible from atop Petřín Hill. Yet just over 100 miles away is another sparkling jewel in the Czech Republic’s crown: Český Krumlov, a city of only 13,000 residents whose 13th-century castle and picturesque riverbanks have brought it not only recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage site but also an increasing influx of tourists that now threatens its very identity.

Former Czechoslovakia’s communist regime, which lasted from 1948 to 1989 before it was ushered out by the Velvet Revolution, left much of Český Krumlov in disrepair. Yet the city’s neglected state lent it a sense of mystery and charm. In the years since, Krumlov—much like the country’s capital, Prague—has been transformed into a tourist wonderland, with historic buildings being renovated and revitalized and ensuing increases in tourist income bolstering the city’s economy.

City streets. Hindol Bhattacharya. CC BY-SA 2.0

As the city has changed, so have the demographics of its visitors. In an interview with Radio Praha, Krumlov’s mayor, Dalibor Carda, explained that an initial boom of Austrian and German tourists after 1989 gave way to an influx of Americans, many of whom settled in the city indefinitely. Today, for locals—whether native-born or transplants—the off-season is a thing of the past, with tour groups flooding the city on a year-round basis. “[I]f you want to have a pristine Krumlov,” writes Jan Velinger in a piece for Radio Praha, “you have to get up very early to ever have its romantic streets, or overlooking castle, ramparts to yourself.” Fed up with the unrelenting crowds, locals have largely migrated to the outskirts of the city, resulting in an exodus of local businesses: Bakeries, hardware stores, and family-owned shops are now difficult to find, having been replaced with bars, restaurants, and hostels catering to short-term visitors.

One of Český Krumlov’s bars, popular among tourists. kellerabteil. CC BY-NC 2.0

In some respects, Český Krumlov has moved to mitigate the encroaching tendrils of tourism, notes reporter Chris Johnstone, pointing to a ban on advertising and the exclusion of cars and buses from the city center. Moreover, just this June, the city established a tariff on buses in an effort to regulate the influx—up to 20,000—arriving each year. The plan is the first of its kind in the Czech Republic, although Salzburg and other Austrian cities have imposed similar measures. Now, all buses rolling into Krumlov must book in advance, navigate to one of two designated stops, and pay the toll of CZK 625, approximately $28.

Tourism has inspired not only legislative changes, but also works of art—as in the case of “UNES-CO,” a 2018 project by renowned conceptual artist Kateřina Šedá. Responding to the profound impact of visitors on the distribution of local populations, Šedá conceived of a work that involved relocating a group of individuals and families to the heart of Český Krumlov for three months at the height of the tourist season. The participants were provided with starter apartments and jobs “on the basis of what Krumlov most needs,” which Šedá deemed to be “the pursuit of normal life.” The title played on the city’s status as a UNESCO World Heritage site and on the Czech words “unést” and “co,” meaning “take away” and “what,” as in “What do visitors get out of this place?” Šedá, whose work often involves social themes and who is famed for relocating an entire Czech village to London’s Tate Modern in 2011, stressed that the project was not intended to be a show for tourists, but rather a social experiment.

Houses along the banks of the Vltava River. P. N. CC BY-SA 2.0

On the opposite side of the artistic spectrum, Huawei—the Chinese electronics behemoth currently facing scrutiny from the U.S. for potential security issues—announced in January that it would build an exact facsimile of Český Krumlov at its headquarters. The Huawei campus, which lies just outside of Shenzhen in the city of Dongguan, will also count Granada, Verona, Paris, Budapest, and Bruges among its plethora of reconstructed European cities. “I heard about it when they started preparing it,” commented Cardo. “The fact that they [are] building it without at least contacting the city does not sit well with me.”

The Krumlov replica may well draw more Chinese tourists, who already represent the largest segment of visitors to the historic city. Yet for embittered locals, the mini-city could be a grimly apt representation of what their home has become: a mere palimpsest of its original iteration, and a cautionary tale depicting how capitalism and tourism can spur unwelcome transformation.

Talya Phelps

Talya hails from the wilds of upstate New York, but dreams of exploring the globe. As former editor-in-chief at the student newspaper of her alma mater, Vassar College, and the daughter of a journalist, she hopes to follow her passion for writing and editing for many years to come. Contact her if you're looking for a spirited debate on the merits of the em dash vs. the hyphen.

The Nasir ol Molk Mosque in Shiraz, Iran: Islamic architecture is one of the gems of Persian culture, as is its traditional music. Wikimedia Commons

Why Traditional Persian Music Should be Known to the World

Weaving through the rooms of my Brisbane childhood home, carried on the languid, humid, sub-tropical air, was the sound of an Iranian tenor singing 800-year old Persian poems of love. I was in primary school, playing cricket in the streets, riding a BMX with the other boys, stuck at home reading during the heavy rains typical of Queensland.

I had an active, exterior life that was lived on Australian terms, suburban, grounded in English, and easy-going. At the same time, thanks to my mother’s listening habits, courtesy of the tapes and CDs she bought back from trips to Iran, my interior life was being invisibly nourished by something radically other, by a soundscape invoking a world beyond the mundane, and an aesthetic dimension rooted in a sense of transcendence and spiritual longing for the Divine.

I was listening to traditional Persian music (museghi-ye sonnati). This music is the indigenous music of Iran, although it is also performed and maintained in Persian-speaking countries such as Afghanistan and Tajikistan. It has ancient connections to traditional Indian music, as well as more recent ones to Arabic and Turkish modal music.

It is a world-class art that incorporates not only performance but also the science and theory of music and sound. It is, therefore, a body of knowledge, encoding a way of knowing the world and being. The following track is something of what I might have heard in my childhood:

Playing kamancheh, a bowed spike-fiddle, is Kayhān Kalhor, while the singer is the undisputed master of vocals in Persian music, ostād (meaning “maestro”) Mohammad Reza Shajarian. He is singing in the classical vocal style, āvāz, that is the heart of this music.

A non-metric style placing great creative demands on singers, āvāz is improvised along set melodic lines memorised by heart. Without a fixed beat, the vocalist sings with rhythms resembling speech, but speech heightened to an intensified state. This style bears great similarity to the sean-nos style of Ireland, which is also ornamented and non-rhythmic, although sean-nos is totally unaccompanied, unlike Persian āvāz in which the singer is often accompanied by a single stringed instrument.

A somewhat more unorthodox example of āvāz is the following, sung by Alireza Ghorbāni with a synthesised sound underneath his voice rather than any Persian instrument. It creates a hypnotic effect.

Even listeners unfamiliar with Persian music should be able to hear the intensity in the voices of Ghorbāni and Shajarian. Passion is paramount, but passion refined and sublimated so that longing and desire break through ordinary habituated consciousness to point to something unlimited, such as an overwhelming sense of the beyond.

Beyond media contrived images

The traditional poetry and music of Iran aim to create a threshold space, a zone of mystery; a psycho-emotional terrain of suffering, melancholy, death and loss, but also of authentic joy, ecstasy, and hope.

Iranians have tasted much suffering throughout their history, and are wary of being stripped of their identity. Currently, economic sanctions are being re-applied to Iran’s entire civilian population, depriving millions of ordinary people of medicine and essentials.

Traditional Persian music matters in this context of escalating aggression because it is a rich, creative artform, still living and cherished. It binds Iranians in a shared culture that constitutes the authentic life of the people and the country, as opposed to the contrived image of Iran presented in Western media that begins and ends with politics.

This is a thoroughly soulful music, akin not in form but in soulfulness with artists such as John Coltrane or Van Morrison. In the Persian tradition, music is not only for pleasure, but has a transformative purpose. Sound is meant to effect a change in the listener’s consciousness, to bring them into a spiritual state (hāl).

Like other ancient systems, in the Persian tradition the perfection of the formal structures of beautiful music is believed to come from God, as in the Pythagorean phrase, the “music of the spheres.”

Because traditional Persian music has been heavily influenced by Sufism, the mystical aspect of Islam, many rhythmic performances (tasnif, as opposed to āvāz) can (distantly) recall the sounds of Sufi musical ceremonies (sama), with forceful, trance-inducing rhythms. (For instance in this Rumi performance by Alireza Eftekhari).

Even when slow, traditional Persian music is still passionate and ardent in mood, such as this performance of Rumi by Homayoun Shajarian, son of Mohammad-Reza:

A Persian woman playing the Daf, a frame drum, from a painting on the walls of Chehel-sotoon palace, Isfahan, 17th century. Wikimedia Commons

Another link with traditional Celtic music is the grief that runs through Persian music, as can be heard in this instrumental by Kalhor.

Grief and sorrow always work in tandem with joy and ecstasy to create soundscapes that evoke longing and mystery.

Connections with classical poetry

The work of classical poets such as Rumi, Hāfez, Sa’di, Attār, and Omar Khayyām forms the lyrical basis of compositions in traditional Persian music. The rhythmic structure of the music is based on the prosodic system that poetry uses (aruz), a cycle of short and long syllables.

Singers must therefore be masters not only at singing but know Persian poetry and its metrical aspects intimately. Skilled vocalists must be able to interpret poems. Lines or phrases can be extended or repeated, or enhanced with vocal ornaments.

Thus, even for a Persian speaker who knows the poems being sung, Persian music can still reveal new interpretations. Here, for example (from 10:00 to 25:00 mins) is another example of Rumi by M.R. Shajarian:

This is a charity concert from 2003 in Bam, Iran, after a horrendous earthquake destroyed the town. Rumi’s poem is renowned among Persian speakers, but here Mohammad-Reza Shajarian sings it with such passion and emotional intensity that it sounds fresh and revelatory.

“Without everyone else it’s possible,” Rumi says, “Without you life is not liveable.”

While such lines are originally drawn from the tradition of non-religious love poems, in Rumi’s poems the address to the beloved becomes mystical, otherworldly. After a tragedy such as the earthquake, these lyrics can take on special urgency in the present.

When people listen to traditional music, they, like the singers, remain still. Audiences are transfixed and transported.

According to Sufi cosmology, all melodious sounds erupt forth from a world of silence. In Sufism, silence is the condition of the innermost chambers of the human heart, its core (fuad), which is likened to a throne from which the Divine Presence radiates.

Because of this connection with the intelligence and awareness of the heart, many performers of traditional Persian music understand that it must be played through self-forgetting, as beautifully explained here by master Amir Koushkani:

Persian music has roughly twelve modal systems, each known as a dastgah. Each dastgah collects melodic models that are skeletal frameworks upon which performers improvise in the moment. The spiritual aspect of Persian music is made most manifest in this improvisation.

Shajarian has said that the core of traditional music is concentration (tamarkoz), by which he means not only the mind but the whole human awareness. It is a mystical and contemplative music.

The highly melodic nature of Persian music also facilitates expressiveness. Unlike Western classical music, there is very sparing use of harmony. This, and the fact that like other world musical traditions it includes microtonal intervals, may make traditional Persian music odd at first listen for Western audiences.

Solo performances are important to traditional Persian music. In a concert, soloists may be accompanied by another instrument with a series of call-and-response type echoes and recapitulations of melodic phrases.

Similarly, here playing the barbat, a Persian variant of the oud, maestro Hossein Behrooznia shows how percussion and plucked string instruments can forge interwoven melodic structures that create hypnotic soundscapes:

Ancient roots

The roots of traditional Persian music go back to ancient pre-Islamic Persian civilisation, with archaeological evidence of arched harps (a harp in the shape of a bow with a sound box at the lower end), having been used in rituals in Iran as early as 3100BC.

Under the pre-Islamic Parthian (247BC-224AD) and Sasanian (224-651AD) kingdoms, in addition to musical performances on Zoroastrian holy days, music was elevated to an aristocratic art at royal courts.

Centuries after the Sasanians, after the Arab invasion of Iran, Sufi metaphysics brought a new spiritual intelligence to Persian music. Spiritual substance is transmitted through rhythm, metaphors and symbolism, melodies, vocal delivery, instrumentation, composition, and even the etiquette and co-ordination of performances.

A six-string fretted lute, known as a tār. Wikimedia Commons

The main instruments used today go back to ancient Iran. Among others, there is the tār, the six-stringed fretted lute; ney, the vertical reed flute that is important to Rumi’s poetry as a symbol of the human soul crying out in joy or grief; daf, a frame drum important in Sufi ritual; and the setār, a wooden four-stringed lute.

The tār, made of mulberry wood and stretch lambskin, is used to create vibrations that affect the heart and the body’s energies and a central instrument for composition. It is played here by master Hossein Alizadeh and here by master Dariush Talai.

Traditional Persian music not only cross-pollinates with poetry, but with other arts and crafts. At its simplest, this means performing with traditional dress and carpets on stage. In a more symphonic mode of production, an overflow of beauty can be created, such as in this popular and enchanting performance by the group Mahbanu:

They perform in a garden: of course. Iranians love gardens, which have a deeply symbolic and spiritual meaning as a sign or manifestation of Divine splendour. Our word paradise, in fact, comes from the Ancient Persian word, para-daiza, meaning “walled garden”. The walled garden, tended and irrigated, represents in Persian tradition the cultivation of the soul, an inner garden or inner paradise.

The traditional costumes of the band (as with much folk dress around the world) are elegant, colourful, resplendent, yet also modest. The lyrics are tinged with Sufi thought, the poet-lover lamenting the distance of the beloved but proclaiming the sufficiency of staying in unconsumed desire.

As a young boy, I grasped the otherness of Persian music intuitively. I found its timeless spiritual beauty and interiority had no discernible connection with my quotidian, material Australian existence.

Persian music and arts, like other traditional systems, gives a kind of “food” for the soul and spirit that has been destroyed in the West by the dominance of rationalism and capitalism. For 20 years since my boyhood, traditional Persian culture has anchored my identity, healed and replenished my wounded heart, matured my soul, and allowed me to avoid the sense of being without roots in which so many unfortunately find themselves today.

It constitutes a world of beauty and wisdom that is a rich gift to the whole world, standing alongside Irano-Islamic architecture and Iranian garden design.

The problem is the difficulty of sharing this richness with the world. In an age of hypercommunication, why is the beauty of Persian music (or the beauty of traditional arts of many other cultures for that matter) so rarely disseminated? Much of the fault lies with corporate media.

Brilliant women

Mahbanu, who can also be heard here performing a well-known Rumi poem, are mostly female. But readers will very likely not have heard about them, or any of the other rising female musicians and singers of Persian music. According to master-teachers such as Shajarian, there are now often as many female students as male in traditional music schools such as his.

Almost everyone has seen however, through corporate media, the same cliched images of an angry mob of Iranians chanting, soldiers goose-stepping, missile launches, or leaders in rhetorical flight denouncing something. Ordinary Iranian people themselves are almost never heard from directly, and their creativity rarely shown.

The lead singer of the Mahbanu group, Sahar Mohammadi, is a phenomenally talented singer of the āvāz style, as heard here, when she performs in the mournful abu ata mode. She may, indeed, be the best contemporary female vocalist. Yet she is unheard of outside of Iran and small circles of connoisseurs mainly in Europe.

A list of outstanding modern Iranian women poets and musicians requires its own article. Here I will list some of the outstanding singers, very briefly. From an older generation we may mention the master Parisa (discussed below), and Afsaneh Rasaei. Current singers of great talent include, among others, Mahdieh Mohammadkhani, Homa Niknam, Mahileh Moradi, and the mesmerising Sepideh Raissadat.

Finally, one of my favourites is the marvelous Haleh Seifizadeh, whose enchanting singing in a Moscow church suits the space perfectly.

The beloved Shajarian

Tenor Mohammad-Reza Shajarian is by far the most beloved and renowned voice of traditional Persian music. To truly understand his prowess, we can listen to him performing a lyric of the 13th century poet Sa’di:

As heard here, traditional Persian music is at once heavy and serious in its intent, yet expansive and tranquil in its effect. Shajarian begins by singing the word Yār, meaning “beloved”, with an ornamental trill. These trills, called tahrir, are made by rapidly closing the glottis, effectively breaking the notes (the effect is reminiscent of Swiss yodeling).

By singing rapidly and high in the vocal range, a virtuoso display of vocal prowess is created imitating a nightingale, the symbol with whom the poet and singer are most compared in Persian traditional music and poetry. Nightingales symbolise the besotted, suffering, and faithful lover. (For those interested, Homayoun Shajarian, explains the technique in this video).

As with many singers, the great Parisa, heard here in a wonderful concert from pre-revolutionary Iran, learned her command of tahrir partly from Shajarian. With her voice in particular, the similarity to a nightingale’s trilling is clear.

Nourishing hearts and souls

The majority of Iran’s 80 million population are under 30 years of age. Not all are involved in traditional culture. Some prefer to make hip-hop or heavy-metal, or theatre or cinema. Still, there are many young Iranians expressing themselves through poetry (the country’s most important artform) and traditional music.

National and cultural identity for Iranians is marked by a sense of having a tradition, of being rooted in ancient origins, and of carrying something of great cultural significance from past generations, to be preserved for the future as repository of knowledge and wisdom. This precious thing that is handed down persists while political systems change.

Iran’s traditional music carries messages of beauty, joy, sorrow and love from the heart of the Iranian people to the world. These messages are not simply of a national character, but universally human, albeit inflected by Iranian history and mentality.

This is why traditional Persian music should be known to the world. Ever since its melodies first pierced my room in Brisbane, ever since it began to transport me to places of the spirit years ago, I’ve wondered if it could also perhaps nourish the hearts and souls of some of my fellow Australians, across the gulf of language, history, and time.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

RELATED CONTENT:

Musical Styles Worth Exploring in Lusophone Countries

VIDEO: Reinventing Electronic Music With Dubai’s Cellist DJ

VIDEO: Mirage of Persia

DARIUS SEPEHRI

Darius is a Doctoral Candidate for Comparative Literature in the Religion and History of Philosophy at the University of Sydney.

VIDEO: Wild Botswana

Filmmaker Martin Harvey documents the wildlife in Botswana, capturing the beauty of Okavango Delta and the Makgadikgadi Pans. The Okavango Delta is a delta in Northwest Botswana teeming with endangered species of large mammals, including cheetahs, white rhinoceros, black rhinoceros, African wild dogs and lions. UNESCO World Heritage protects two million hectares of this pristine delta. Okavango is an important site of support for elephants, as Botswana has the largest elephant population in the world. The delta is also species-rich in terms of plant life, possessing over 1,000 plant species. The Makgadikgadi Pans lie south-east of the Okavango Delta. From February to March, zebras, oryx, wildebeests, impalas and springbok graze Makgadikgadi National Park. The national park has never been inhabited by humans and is rather remote.

Indian Cuisine Is More Than Just Curry

From the steamed seafood dishes of coastal Odisha to the smoky meat skewers of the northern Punjab region, Indian cuisine has an incredible range to offer.

Indian cuisine.CC0.

Despite the popularity of dishes like butter chicken and naan in westernized Indian restaurants, the rich history of the Indian subcontinent actually has a surprisingly diverse cuisine that ranges far beyond the bright red curries and steaming roti that often comes to mind. Thanks to the diverse geography across the country, each region has its own go-to meats, vegetables, grains and most importantly, spices.

Indian cuisine has also been hugely impacted by its colonial history, and not just the British one that we are familiar with; the Portuguese and French also set up colonies across the southern and western parts of the country—both of which influenced the cooking styles of those regions. This, in addition to flavors from neighboring Persia, China and a variety of religious influences, have transformed Indian cuisine into a hugely popular cuisine not just across Asia, but in the western world as well.

Setting the south Indian plate. Rajesh Pamnani. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

The coastal state of Kerala lies on the southwestern tip of India and is most well known for its unique geography and natural beauty. This makes it an ideal travel destination for people interested in Ayurvedic healing, a centuries old natural medical technique that relies on a number of herbal remedies. Ayurvedic cooking is based on trying to re-balance the patient’s internal constitution using the six rasas or flavor profiles: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, pungent and astringent. The local food and culture are both heavily influenced by the region’s 200 years as a colony under the rule of Arab settlers, the Portuguese and finally the Dutch, which added to the large Christian population in the area.

Keralan cuisine is known for its generously seasoned seafood dishes, as well as its use of tapioca, banana leaves and most famously, coconuts. The long monsoon season in this region of the country is conducive to paddy farming, making rice and rice-flour based dishes like idli and appam, different types of rice cakes and common dietary staples. Because of its coastal location, Kerala received huge imports of spices from the Middle East, which to this day can be seen in the extensive use of cardamom, cinnamon, chili and black pepper in both seafood curries and vegetarian stews. A popular dish amongst Western travelers is vindaloo, which is the local south-western variation on a Portuguese dish known as carne de vinha d’alhos, a pork dish flavored with garlic, wine and vinegar.

Odishan pakhala platter. Lopanayak. CC BY-ND 2.0.

Formerly known as Orissa, the mountainous state of Odisha is home to more than 700 beautifully preserved Hindu temples, many of which are still in use by the state’s huge Brahman population to this day. The local food is heavily influenced by the many thriving tribal cultures as well as the religious restrictions of the social caste system, which survived despite the region being part of the Muslim Mughal empire and later the southern Marathas dynasty before coming under British rule in the early 1800s.

Because of the prominent role of religion in Odia life, most of the local cuisine is based on foods believed to be the favorites of Hindu gods so that they can be given as offerings. Most dishes are prepared with ghee, a form of clarified butter, instead of regular cooking oil, and unlike most other regional Indian cuisines, not a lot of chili is used either. The local climate is favorable for the growth of mustard leaves, which is a common flavoring agent in a number of popular curries and chutneys. Odia desserts are also very unique to the region given their heavy use of dairy products, especially paneer, a local preparation of cottage cheese. It can be deep fried with brown sugar to make jalebis and is a very popular snack because of the sugar syrup it soaks in. Paneer can also be scrambled and soaked in milk, giving it a much softer and fluffier texture before adding various flavors to make a porridge-like dish called kheer. Most commonly, the raw paneer is shaped into cake-pop sized balls and boiled in sugar syrup to make gulab jamun and rasgullas.

Traditional Meghalayan meal. Jakub Kapnusak. CC BY 2.0.

The northeastern state of Meghalaya is one of the Seven Sister States tucked between Bangladesh and Bhutan, with nearby Myanmar not too far to the east. It is located entirely on a mountain plateau and is often subject to heavy precipitation, which gives it a unique range of local vegetation. Tribal cultures are still very prominent, many of which are reminiscent of more East Asian groups due to the region’s proximity to China, which also heavily influences the local cuisine.

The two most staple ingredients in Meghalaya cuisine are rice and pork, especially when prepared with the local spice mix known as purambhi masala. In fact, local tribes even brew their own rice liquor, a clear yellow liquid called kiad that tends to contain up to 70% alcohol and is believed to have healing and curative properties. Rice noodles and dumplings made with rice paper wrappers are also very popular in the area. In parts of the state with higher altitude, locals may substitute pork for yak meat instead, which is a local delicacy that also shows the heavy influence of nearby Bhutan. Many of the local vegetable dishes make use of fermented soybeans, bamboo shoots, tree tomatoes, banana flowers and sesame seeds for texture and flavor.

Punjabi food. What The Fox Studio. CC BY-NC 2.0.

Punjab is a state located in the northwestern part of India, right on the border with Pakistan. While Sikhs make up the majority of the local population, many are descendants of Greek and Aryan invaders who came into the country thousands of years ago. The state is also completely landlocked and receives most of its irrigation from the Sutlej and Beas rivers that flow through it. This, in addition to extremely hot and dry summers, makes the area very favorable for growing wheat, which earned the state the nickname of “India’s bread-basket”.

Besides garam masala, the local spice mix composed of cumin, nutmeg, cardamom and black pepper among other condiments, pickled vegetables are a local favorite to be eaten alongside the tandoori dishes unique to Punjab. The meter-tall clay tandoor ovens are often buried in the ground and house a small wood charcoal fire at their base. They are filled with meat skewers that have been soaked in yogurt based marinades while pre-rolled naan are stuck to the sides to bake. Aside from the dry tandoori meats, Punjabi cuisine also features a variety of sauce-heavy dishes, including murgh makhani which is famously known worldwide as butter chicken. Another local favorite is kulfi, the Punjabi take on ice cream made from churned milk and sugar, often flavored with fresh mango, especially during the hot summer months.

Tanaya Vohra

Tanaya is an undergraduate student pursuing a major in Public Health at the University of Chicago. She's lived in Asia, Europe and North America and wants to share her love of travel and exploring new cultures through her writing.

5 Cave Painting Sites that Paint a Picture of Prehistoric Life

Cave paintings provide valuable knowledge about the culture of prehistoric civilizations. These five cave painting sites contain some of the oldest and most fascinating prehistoric art from around the world.

Lascaux Cave paintings in France. Bayes Ahmed. CC BY 2.0.

From Argentina to Bulgaria, humans have been creating art since the dawn of civilization. This art is sometimes the only way to glean certain details about prehistoric culture in various parts of the world. Each of the following five sites provides a unique insight into culture, religion, social life and more, as early as the Stone Age, which spanned from about 2.5 million years ago to 5,000 years ago.

1. Bhimbetka Rock Shelters - India

Paintings of animals at Bhimbetka Rock Shelters. Arian Zwegers. CC BY 2.0.

The cave paintings at the Bhimbetka Rock Shelters in Madhya Pradesh, India, date from the late stone age to early historic period. These paintings and carvings reflect many realities of prehistoric life, depicting animals, religious rituals, agricultural practices and social life. Many artifacts have also been found in the Bhimbetka Rock Shelters, such as stone tools likely used for agricultural purposes. Because of the significant facts about early Indian life that have been provided by this cave art, the Bhimbetka Rock Shelters have been declared a World Heritage Site.

2. La Cueva de Los Manos - Argentina

Handprint paintings. Ryan Somma. CC BY-SA 2.0.

La Cueva de Los Manos or “the cave of hands” is aptly named; this cave painting located in Santa Cruz, Argentina is mostly a collection of handprints, estimated to have been created between 9,500 and 13,000 years ago. The handprints are believed to have been made from mineral pigments by early hunter-gatherer tribes. The meaning of the hands is unknown, but some have theorized they represent an initiation of teen boys into adulthood, due to the size of the hands. In addition to the hands, the cave also contains paintings of animals such as llamas, birds and pumas.

3. The Magura Cave - Bulgaria

Paintings at Magura Cave. Klearchos Kapoutsis. CC BY 2.0.

The Magura Cave in Belogradchik, Bulgaria contains an extensive number of paintings made of bat droppings between 4000-8000 years ago. There are approximately 700 paintings in the cave. The paintings depict anything from people dancing and hunting to religious rituals. The cultural significance of the themes painted, as well as the sheer number of paintings, makes the Magura Cave a significant cultural monument.

4. Lascaux Cave Paintings - France

Painting of an animal in Lascaux Cave. Christine. McIntosh. CC BY-ND 2.0.

The paintings of the Lascaux Cave in Dordogne, France are estimated to be 15,000-17,000 years old, stumbled upon by a group of teenage boys in 1940. Interestingly, among the approximately 600 paintings and 1,500 engravings, there is only one image of a human, making this site differ significantly from the others mentioned, which all depict daily human life in some way. In fact, the human form painted has the head of a bird. Other than this, most of the paintings are of various animals, both real and imaginary. What would be known as a modern day unicorn is even depicted. The Lascaux Cave tells us more about the imagination and storytelling practices of the people of prehistoric France than it does their concrete, daily practices.

5. Laas Geel - Somalia

Cow at Laas Geel. Najeeb. CC BY- SA 2.0.

Laas Geel, in Hargeisa, Somalia, is a collection of rock paintings discovered in 2002. Laas Geel depicts cows, painted with a vibrant red pigment. What is interesting about these cows is that they appear to have some type of ceremonial necklace or hanging around their necks. Many of the cows also appear to be wearing crowns or have some sort of halo-like object around their heads. The cows are often depicted next to humans and dogs. These depictions indicate that cows played some sort of ceremonial role, bringing up important questions about early religion and culture in Somalia.

Calliana Leff

Calliana is currently an undergraduate student at Boston University majoring in English and minoring in psychology. She is passionate about sustainability and traveling in an ethical and respectful way. She hopes to continue her writing career and see more of the world after she graduates.

6 Things to Know About Kilimanjaro From a Past Climber

Tanzania is home to the tallest mountain in Africa, Mount Kilimanjaro. However, here are six things everyone should know before deciding if they are ready to brave the mountain.

Mount Kilimanjaro. Gary Craig. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Mount Kilimanjaro was created by three volcanic cones called Kibo, Shira, and Mawenzi about 2.5 million years ago. Standing at 19,341 feet, it is home to almost every ecological system: cultivation, forest, heather-moorland, alpine desert, and arctic summit zones. Climbers pass through each of these ecosystems in stages based on elevation. What many may not realize is that Kilimanjaro is dormant, not dead. This means the dormant Kibo cone could erupt again.

I made the climb in January. I will be extremely honest; it was quite miserable at times. It is simply impossible to put into words what hiking a mountain like that will do to you. From the daily struggles of altitude sickness and the feeling of breathing almost nonexistent air, to being the most exhausted you have ever been in your life, dehydrated, starving but unable to keep food down, to having to use the “bathroom” behind a rock right on the side of the trail. I even saw someone lose their life from cardiac arrest. Though it is, thankfully, not a common occurrence, it was rough.

With that said, the struggles make the reward that much sweeter. When I reminisce on my experience, I remember the hard times, but the beautiful moments I was fortunate enough to be a part of are more prominent. The dance and guitar sessions the group would have on our breaks, the feeling of being in a place completely isolated from the world, climbing higher than the plane that got me there, finding a new strength in myself that otherwise would have remained unknown. Kilimanjaro is a monster mountain, but it was the best experience of my life.

1. “Pole, Pole” are words to live by

“Pole, pole” translates to “slowly,” and I cannot stress enough how important this simple phrase is. It doesn’t matter what your physical abilities are, if you do not take your time, you will be hurting. Taking at least five days (depending on your route), this hike is no joke. It’s important to put your pride aside and accept that you might not be the fastest person to get up the mountain, and that’s completely OK! This was something I quickly learned. On the first day, I tried keeping up with the front of my group and very quickly learned I simply wouldn’t make it all six days if I kept that up. No matter what your pace, a guide will always stay by your side, carry things for you if you are struggling, and motivate you to keep going. Guides want you to succeed just as much as you want to, so definitely listen to their advice. They’re lifesavers—literally!

2. You will create amazing connections with your guides and porters

Photo taken by John Willard, my guide on my Kilimanjaro hike.

Your team on Kili will be absolutely amazing, no doubt about it. They will do whatever they can to help you summit, practically carry you if need be. They are extremely selfless and charismatic people, and they make the experience so much more enjoyable. Porters are the men and women who dedicate themselves to carrying all of your gear up the mountain, setting up camp, cooking meals, and creating a vibrant hike experience. Guides spend time with you on your hike—helping you stay on the trail, keeping an eye on your health, and really just guiding you to the summit. On my trip, the team loved to dance and sing and always invited us to join them on breaks and when at camp. They welcomed us to become immersed in the culture and understand the historical importance of Mount Kilimanjaro. The guides and porters truly enhanced the experience, so much that you simply won’t want to leave them. You will want to have WhatsApp downloaded on your phone so you can put in your favorite porters’ and guides’ numbers; when you get home, having those connections will keep a piece of Kili in your heart forever.

3. You will probably get sick

I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but if you decide to climb Kili, you will most likely find yourself experiencing at least some altitude sickness symptoms. It’s inevitable when going up 19,000 feet. Headache, nausea, and exhaustion are some of the more common symptoms. They will not end your hike early, but they will make life a little more miserable on the mountain. You just have to push through! Your guides will keep track of your vitals every day and will encourage you to eat and drink as much as your body will allow—food and water will be your best friend up there. You may hear people say that getting to high elevations eliminates your appetite, and this is very true. I found it hard to stomach even soup broth on my hike. It is best to pack some of your favorite snacks to help get past your lack of appetite. Many people, including myself, take altitude sickness pills to help combat symptoms. They are worth taking as long as they don’t cause negative effects on your body. They helped lessen the severity of my symptoms.

4. It is like being in a movie

Aerial View of Mount Kilimanjaro.Takashi Muramatsu. CC BY-ND 2.0.

Kilimanjaro is absolutely breathtaking. I remember feeling like I was living in a Star Wars scene for the majority of the hike. The sunsets and sunrises are unlike anything you will ever see again. Barranco Camp, where you will find yourself after hiking from Shira to Lava Tower to Barranco, was the highlight of my entire hike. Beautiful waterfalls, camping on a cliff in the clouds, being surrounded by the massive Barranco Wall (which you will be climbing up the next morning)—it is a beautiful and untouched part of the world. It makes the everyday battle worth it. When you’re feeling like giving up, just stop and turn around. The view you see will give you the courage to keep going.

5. You may see some horrific things

Barranco Wall on Mount Kilimanjaro. Haleigh Kierman

This is not a guarantee, but it is best to know what can happen. During my hike, I witnessed a man pass away right on the trail from cardiac arrest. I never thought I would see something like this, so it is important you know that really anything is possible before deciding if the hike is right for you. It is much more common to see people get physically sick or use the “bathroom” in clear sight, which are things we can typically move on with. With that said, there is always the possibility you can see something more severe. Do not fear though, Kilimanjaro is remarkably safe given its size. Around 30,000 hikers attempt each year with only a 0.03% death rate. If you know and trust your individual abilities and health, there is little to be concerned about.

6. You will discover an unimaginable amount of self-pride when you finish

Sunrise on Summit Day. Haleigh Kierman

Summit day: it’s killer. You begin the final trek to the summit around 11:30 p.m. and get to the top around 8 a.m., depending on your pace. At this point, you will be sleep-deprived, feeling as though you are suffocating with every step you take because the air is so thin. But somehow, you will find that strength in you to keep going. And when you finally make it to the top, all you will feel is euphoria. You may even shed a tear or two. Kili will push you to your limit and then past that. You really will discover a new part of yourself you didn’t know was there. If you set your mind to conquering Kilimanjaro, you can do it. It will be one of the hardest things you will ever do, but the reward is a feeling of accomplishment that will change your life forever.

Haleigh Kierman

Haleigh is a student at The University of Massachusetts, Amherst. A double Journalism and Communications major with a minor in Anthropology, she is initially from Guam, but lived in a small, rural town outside of Boston most of her life. Travel and social action journalism are her two passions and she is appreciative to live in a time where writers voices are more important than ever.

The Maha Kumbh Mela Pilgrimage in India

This Indian pilgrimage and festival attracts 100 million spirituality-seeking visitors—pilgrims, saints, seekers, philosophers, gurus and disciples. It happens every 12 years at the sacred confluence of Ganges and Yamuna rivers, and the next 6 week event happens in 2025.

Read More7 Famous Trees of The World

Today, trees face threats such as deforestation, habitat reduction and fires fueled by climate change. Despite it all, these seven tree species continue to symbolize the lands they call home.

Forest in Italy. Giuseppe Costanza. CC0 1.0

As urbanization and overpopulation fuel clearcutting around the globe, these trees stand in their own glory. Granted protection status, having festivals in their honor and attracting admirers from around the world, this is a list of trees that have made a name for themselves and their roots.

1. Baobabs, Madagascar

The Avenue of Baobabs. Zigomar. CC BY-SA 2.0

For many, the Avenue of Baobabs is the first thing that comes to mind when they hear the word "Madagascar." Approximately 50 baobab trees line the dusty road and surrounding groves between Morondava and Belon'i Tsiribihina. Endemic to the island, the trees are referred to as "renala," or "mother of the forest," by locals. The avenue has gained international fame, attracting crowds during sunset and became the first protected natural monument in Madagascar in 2007 when it was granted temporary protection status.

2. Yucca Trees of Joshua Tree State Park, California, USA

YuccaTree in Joshua Tree State Park.Esther Lee. CC BY 2.0

The yucca trees, for which California's Joshua Tree State Park was named, got the nickname “Joshua” from a band of Mormons traveling from Nebraska. The lunar desert climate is ideal for yuccas, which have grown adapted to storing water inside their trunks and twisted branches. They are said to be able to survive on very little rainfall a year, but if the weather happens to bring rain in the spring, the yuccas will give thanks with a sprout of flowers.

3. Cherry Blossoms, Japan

Cherry blossoms at Mount Fuji. Tanaka Juuyo. CC BY 2.0

The cherry blossom, or sakura, is considered the national flower of Japan. Hanami, the Japanese custom of enjoying the flowers, attracts locals and visitors to popular viewing spots across the country during the annual Cherry Blossom Festival. Peak bloom time depends on the weather, and the cherry trees have been flowering earlier and earlier each year due to climate change. On average, the cherry trees reach peak bloom in mid to late March and last around two weeks.

4. Jacaranda Trees, Mexico City, Mexico

Jacaranda trees. Tatters. CC BY-NC 2.0

Every spring, the already vibrant streets of Mexico City are lined with the jacaranda's violet bloom. President Álvaron Obregón commissioned Tatsumi Matsumoto, an imperial landscape architect from Japan, to plant the trees along the city's main avenues in 1920. Matsumoto was the first Japanese immigrant to come to Mexico, arriving a year before the first mass emigration in 1897 and staying until his death in 1955. Today the jacarandas are considered native flowers and symbolize international friendship.

5. Rubber Fig Trees, Meghalaya, India

Double-decker living roots bridge. Ashwin Kumar. CC BY-SA 2.0

Widely considered the wettest region in the world, villagers of the northeast Indian state of Meghalaya are separated by deep valleys and running rivers every monsoon season. The living roots bridges are handmade by the Khasi and Jaintia people with the aerial roots of rubber fig trees. The bridges grow strong as the tree's roots thicken with age, holding more than 50 people and lasting centuries if maintained. The double root bridge, pictured above, is almost 180 years old, stands at 2,400 feet high and suspends 30 meters in length.

6. Argan Trees, Morocco

Goats in an Argania tree. remilozach. CC0 1.0

Built to survive the Saharan climate, Argan trees are endemic to southwestern Morocco. Their scientific name, Argania, is derived from the native Berber language of Shilha (also known as Tashelhit). The trees grow fruits used to make argan oil, an ingredient found in many beauty products. Rights to collect the fruit are controlled by law and village traditions, while several women's co-operatives produce the oil. Goats are frequently photographed climbing argan trees and help in the production process by eating the nuts, leaving the vitamin-rich seeds for the locals to collect.

7. Trees of the Hoh Valley, Washington, USA

Trees in Hoh Valley. James Gaither. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

On the Pacific side of the Olympic Mountains in the Hoh Rainforest, lush yellow and green moss covers some of North America's giants, including the Sitka Spruce, Red Cedar, Big Leaf Maple and Douglas Fir. As a result of the area's average 140 inches of rainfall per year, the moss is not only enchanting but beneficial. Moss plays an essential role in supporting the forest's biodiversity; like a sponge, it decays, absorbs and finally releases nutrients for the trees’ roots to feed off.

Claire Redden

Claire is a freelance journalist from Chicago, where she received her Bachelor’s of Communications from the University of Illinois. While living and studying in Paris, Claire wrote for the magazine, Toute La Culture. As a freelancer she contributes to travel guides for the up and coming brand, Thalby. She plans to take her skills to London, where she’ll pursue her Master’s of Arts and Lifestyle Journalism at the University of Arts, London College of Communication.

VIDEO: Journey Through Thailand

This footage of Thailand serves as the second installment in Vincent Urban’s series: “In Asia.” The video features glimpses into the vibrant streets of Bangkok and the natural scenery of Northern Thailand. He also features footage from the small but lively town of Pai, located near a mountain base in Northern Thailand. The director includes evocative imagery of Buddhist temples from his visit to the city of Chiang Mai, capital of Chiang Mai province. German director Vincent Urban, based in New York City, concludes the episode teasing his next stop, Laos, for the following installment of the series.

5 Alcoholic Drinks Made By European Monks

Catholic monks throughout Europe make and sell liquors, beers and wines to travelers, using recipes they have cultivated and perfected over centuries.

Read MoreTravel and Work for Food on Organic Farms

Organic farms look for travelers to help in exchange for housing, meals and an opportunity to learn—providing a unique mode of affordable, ethical travel.

Organic farm in Cyprus, Greece. George M. Groutas. CC BY 2.0.

Worldwide Opportunities on Organic Farms (WWOOF) is the most widespread and popular organization that pairs people interested in volunteering on organic farms throughout the world with host families who run their own organic farms. The idea is that volunteers would be just that: unpaid volunteers, who work part-time on a close-knit and often family-run farm in exchange for free housing and meals with the family. In fact, WWOOF bans any exchange of money between the host and the volunteer. Often, these volunteer stints are short (a few weeks) or part-time, allowing for the volunteer to obtain paid work and/or spend time exploring the area they are living in while also growing the food they will eat during their stay, immersing themselves in culture, helping a local organization and learning from experienced farmers. Below are some detailed opportunities from every continent in the world.

North America: Consecon, Canada

Stonefield Alpaca Farm in Consecon, Canada is a 100-acre family-owned and operated farm powered by solar panels and windmills. The owners are looking for volunteers to help maintain the straw bale home they built together, grow their own food and take care of the animals (alpacas and poultry). They hope to become completely self-sufficient in terms of food, and that volunteers can help them do so while also learning from them and exploring Ontario. Learn more here.

South America: Belize City, Belize

An individual who bought and began his own 14-acre pesticide-free, organic farm in Belize City, Belize offers an opportunity to help develop his farm further in terms of sustainable energy production and other sustainable farming methods. He became a host because he was a WWOOF participant in the past. His farm has goats, monkeys, parrots and sheep. Responsibilities would include taking care of the animals, gardening, landscaping and sharing ideas on how to improve the farm’s organic practices. Learn more here.

Africa: Apam, Ghana

This family-owned farm in Apam, Ghana is not only a farm located on the coast, in the center of a fishing community, but also an educational and charitable center focused on agriculture and helping the larger community. The hosts are looking for volunteers to help with typical farming tasks, such as taking care of animals and harvesting, as well as build ecological houses and participate in the local fishing. This is a unique opportunity to not only help the environment and one local family, but the entire community as well. Learn more here.

Australia: Upper Kangaroo River

Winderong Farm is a cooperation of 10-15 employees and volunteers working together to revive their surrounding environment in Upper Kangaroo River, Australia. They’re looking for volunteers interested in conservation to work on composting, permaculture and regeneration of the Australian bush. This farm differs from most as it is a larger, community-based effort as opposed to a small family-run farm. Learn more here.

Asia: Kampot, Cambodia

Nakupenda Farm in Kampot, Cambodia is a family and community farm focused on sustainability. They are completely sustainable in terms of energy and are working towards growing all of their own food. They would like volunteers to help harvest food and help them reach their goal of becoming entirely self-sufficient. They have also worked on projects in the past such as building earth houses and solar dehydrators, which dry fruits and vegetables to preserve them. Nakupenda Farm sits on 3.5 acres of land. Learn more here.

Passive solar dehydrator. Colleen Taugher. CC BY 2.0.

Europe: Hvolsvöllur, Iceland

The Farm Buland is a certified organic dairy farm run by three generations of one family. They would primarily be looking for help with the cows and other livestock, such as chicken, horses and sheepdogs. The owner is passionate about environmentalism and has studied natural healing and medicine. They have over 50 humanely treated cows, providing an opportunity to work on a large-scale ethical and organic farm. Learn more here.

These are only a few examples of the types of farms looking for volunteers; there are hundreds of local and family-owned farms all over the globe searching for people passionate about agriculture and the environment to help them while learning from their experience. In addition to WWOOF, potential volunteers can find more opportunities through similar organizations like World Packers, as well as through the websites of individual independent farms on the lookout for volunteers, such as Red Hook Farm.

Calliana Leff

Calliana is currently an undergraduate student at Boston University majoring in English and minoring in psychology. She is passionate about sustainability and traveling in an ethical and respectful way. She hopes to continue her writing career and see more of the world after she graduates.

TikTok Creator Highlights Living Near North Pole

Living with no running water, and four months of complete darkness sounds like an extreme way of living for most of us, but for Tik Tok creator Cecilia Blomdhal it is her daily normal. By showing her minimalist living in the most extreme conditions she has gained her over a million followers.

Trail Angels and Trail Magic on the Appalachian Trail

As thru-hikers backpack the Appalachian Trail from Maine to Georgia, people dedicated to assisting the hiking community volunteer their time to perform services to the hikers who need it most.

The Appalachian Trail in the fall. Nicholas T. CC BY 2.0.

Sporadically stationed along the Appalachian Trail (AT)—a hike that spans through 14 states starting in Maine and coming down through Georgia—volunteers dubbed “Trail Angels” set up to assist thru-hikers on their journey across the mountains.

The Appalachian Mountain Range has become one of the three major hiking trails in the U.S. and a welcome challenge for some of the most experienced backpackers in the country. The Appalachian Trail Conservatory (ATC) website states the trail is over 2,190 miles, and to do it in one trip “typically takes five to seven months.” Despite the challenge, thru-hikers travel in droves to attempt the AT every year, facing the physical and mental fatigue that accompanies months of full-day hikes, low calorie meals and poor sleeping and hygiene conditions. But in tests of true strength, a little help is always welcome, and the thru-hiking community shows an aptitude for providing some magic just when it’s needed most.

A thru-hiker on his journey. @Zen. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Trail Angels are volunteers who provide free services to thru-hikers during their journey across the mountains, a fitting name for their selfless acts of kindness. Trail Angels typically provide what has been called Trail Magic. The Appalachian Trail Conservatory explains Trail Magic as “finding what you need most when you least expect it,” emulating why the work Trail Angels do is so special; it is an unexpected surprise in an environment where everyday is so monotonous - hiking, eating, camping and repeating the process for days on end. Further, in stretches of the Appalachian Trail where the terrain is most daunting, Trail Magic can make a world of difference to thru-hikers contemplating quitting or even more severely, thru-hikers in desperate, life-or-death need of food, water, or shelter.