During this time where everything in our life is completely run within the parameters set by COVID19, the only way we might get the chance to see a city is to fly through it, like a bird. These Milanese filmmakers found a way to do just that. Check out this short documentary, shot by a drone flown through the neighborhoods of Milan, which gives us a chance to witness that life is still happening.

Nests of Gold: All About Birds Nest Soup

“A visual journey following one of the world's most expensive foods. From its creation in the remote island caves of the Philippines, to its transformation into the legendary Cantonese dish of ‘Bird's Nest Soup’ at a 3 Michelin Star restaurant, this film examines this strange delicacy, and the different lives that are touched by it.”

Meet the Helpers Rising Up During the Coronavirus Pandemic

Mister Rogers taught us that when things feel scary, “look for the helpers.” Today, people all over the world are stepping up to help their fellow human beings during the COVID-19 pandemic. This one’s for them—for the doctors, nurses and paramedics risking their own lives to keep us healthy; for those in the garment industry making masks for the workers on the front lines; for the chefs, the kitchen and delivery workers making sure no one goes hungry. These are the everyday heroes showing kindness and strength when we need it the most.

There are so many ways you, too, can help. If you’re looking to lend a hand, here are just a few ways you can make a difference.

Make Masks

The folks at the Minnesota Opera costume shop, EquiFit (a company that designs gear for horses and riders), Stitchroom (a custom home goods outfit) among so many others are retooling their operations to make and deliver masks to those working on the frontlines. If you’ve got a sewing machine and some free time, you can, too. Here’s what you would need.

For supplies, the most effective household materials to transform into masks include vacuum cleaner bags, dish towels, T-shirts, and pillowcases. Find more information about the efficacy of different materials right here.

There are many different types of masks you can create, from double-layered, to those with a pocket for a reusable filter. Here’s a tutorial to one of the simplest masks you can make from home. Find more mask-making resources here.

There are many different places you can donate your masks, including your local hospital. If you are looking for organizations that are helping to distribute, check out Stitchroom, and join their Facebook group for more maker resources.

Give Food

Chefs like José Andrés and Marcus Samuelsson are working to bring relief to those affected by COVID-19 through World Central Kitchen. So many other small restaurants and businesses in the US and beyond are donating food to make sure no one has to go hungry.

Save the Children and Blessings in a Backpack have teamed up with school districts to provide meals to students. You can donate to Save the Children here, and Blessings in a Backpack here.

Older adults are also among the most vulnerable right now. Meals on Wheels provides home delivery of food to seniors, and needs resources now more than ever. You can donate here.

Food banks are also facing an increased need during this time. Feeding America has set up a COVID-19 Response Fund to support its 200 food banks nationwide, and has set up mobile, drive-through distribution points.

Support Healthcare Workers

People like 16-year-old pilot TJ Kim and the motorcyclists at Masks for Docs are going the distance to deliver PPE to healthcare workers. Here’s how you can help, too.

The World Health Organization, the UN Foundation and the Swiss Philanthropy Foundation have come together to create the COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund to finance diagnostic tests, buy supplies for healthcare workers and fund research efforts. You can donate here.

International Medical Corps is working with WHO to provide training, supplies and emergency medical response planning in high-risk locations. You can donate here.

Direct Relief is supplying health authorities in the US and China with protective equipment they need right now. You can donate here.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON GREAT BIG STORY

Traditional Mosque. Clay Gilliand. CC 2.0

The Impact of COVID-19 on Ramadan

Since the beginning of the year, the global pandemic has successfully disrupted everyone’s lives in some shape or form. Now however, Muslims especially around the world are feeling the weight of it as they start to practice Ramadan but cannot do so as traditionally practiced for thousands of years. It is a holy time for them, observed on the ninth month of the Muslim calendar year and is a time to reflect on their faith and community. However, with the virus spreading and concerns for health are still a major issue, those practicing Ramadan are unable to come together, worship and reflect on what their faith means to them.

What is Ramadan?

A time to reflect on one’s faith and focus on community and charity, Ramadan is a holiday that has been celebrated for thousands of years and serves as a commemoration of Muhammad’s first revelation. During this time, which lasts between twenty-nine and thirty days, adult Muslims who do not meet the exceptions are required to fast from dawn to dusk. Throughout the day, they devote their time to the Quran, performing charitable deeds and striving for purity that is heightened throughout this time period.

Mecca, the Holiest of Sites

Mecca, Saudi Arabia is seen as the holiest site to Muslims and is usually full to capacity during Ramadan with worshippers from around the world. But now with shelter-in-place orders, mass gatherings are still illegal, causing mosques to be closed to the world. “Saudi Arabia’s grand mufti, Sheikh Abdul Aziz bin Abdullah Al Al- Sheikh, has told people to pray at home, including the special nightly Ramadan prayers called Taraweeh that attract throngs to mosques.” Their sahur (pre-dawn meal) and iftar (breaking of fast at dusk) are also ordered to be done only with family, not with the community they are so used to being with. Lastly, Saudi Arabia has banned all travel “during Ramadan”, resulting in millions of families separated from their family during the holiday. Ultimately, the community that is so strong during this time has been kept apart by the virus, isolating those when they lean on their community the most.

How Fasting has been Impacted in Developing Countries

In some countries, fasting has proved harder as the distribution of food has not been equal and many families have found themselves without any food. In Burkina Faso, a landlocked country in West Africa, Karim Bamago states, “I am managing, but it’s difficult to fast knowing there will be nothing at the end of it.” Around the violence-stricken country, the pandemic has only intensified the disruption of food supplies. They have reported that “they really need help…water is an issue and there is no healthcare.” With very little water, they are even finding it difficult to wash their hands and keep within the guidelines for COVID-19. The once joyously celebrated holiday will now be observed with the same revere as previous years, with Muslims only able to keep praying to Allah to keep them safe. Those that have brought them food in the past are coming “less and less” and families are starting to feel the impact of COVID-19 on all fronts, physically, mentally and now spiritually.

Muslims around the world are finding it hard to keep the same joy in their hearts while celebrating a holiday centered on faith, charity and community. A once beautiful time has been shoved into the shadow of isolation as millions of Muslims find themselves celebrating Ramadan as they never have before. While COVID-19 has helped bring families closer, it has ultimately served to disrupt the lives of people who need community now more than anything else.

Elizabeth Misnick

is a Professional Writing and Rhetoric major at Baylor University. She grew up in a military family and lived in Europe for almost half her life, traveling and living in different countries. She hopes to continue writing professionally throughout her career and publish her writing in the future.

Graphic of Mona Lisa wearing sanitary mask. Folsom Natural. CC BY 2.0

Studying Abroad Amid Lockdown

According to the Institute of International Education, the University of Georgia ranks thirteenth in the nation for the number of students who study abroad. With over one hundred faculty-led programs and nearly 2,000 students studying abroad each year, global experiential learning promises an expanded worldview and diversified education.

During my second year pursuing a Spanish degree at the University of Georgia, I decided to study abroad in Valencia, Spain. Expecting to explore Europe for six months, I eagerly boarded a plane from Atlanta to Madrid with three bulky suitcases. From December to January, I spent my days attending lectures at a local university, traversing the Spanish countryside, and conversing with locals. Amid my cultural immersion, reports began to emerge about the coronavirus outbreak in China. I naively believed this novel disease would not impede trips to England, France, and Portugal.

By February, however, COVID-19 had inundated Europe, forcing many study abroad students to return home. UGA’s Office of Global Engagement, like many universities, consequently issued this statement: “The University of Georgia recognizes that international travel, communication, and partnerships are essential to UGA's academic, research, and outreach mission and supports these endeavors. Countries and areas that carry U.S. State Department Travel Advisory Level 3/4 require special consideration and review to manage and mitigate risk, and in many circumstances, require the avoidance of travel altogether.” After a soccer match against Milan, a coronavirus epicenter, Valencia’s travel advisory was raised to a level 2.

Fearing my study abroad program would abruptly end, I intended on visiting as much of Europe as possible. For three consecutive weeks, I took advantage of cheap airfare and traveled to London, Paris, and Lisbon. Each city’s hotels, restaurants, and tourist attractions were practically vacant. I had imagined the streets of Paris, the city of romance and culture, to be bustling with music and lovers walking hand in hand. Yet, during the last week of February, Paris was eerily still. I waited for five minutes to climb the Eiffel Tower and Arc de Triomphe, while most tourists wait over an hour. In the Louvre, which normally averages 15,000 visitors per day, I observed artwork like the Mona Lisa and Venus de Milo in silence. Even Champs-Elysees, the most famous street in Paris, was deserted. Apart from the occasional Parisian in mask, it seemed I had the city to myself. Days after departing Paris, the government announced, “All gatherings of more than 5,000 people in confined spaces will be cancelled.” Infamous sites that I had just toured, like the Louvre and Eiffel Tower, were closed indefinitely.

On March 11, more chaos ensued as the World Health Organization’s Director General, Tedors Adhanom, declared the coronavirus a pandemic, stating, “We have rung the alarm bell loud and clear.” The following day, while I slept in my Valencia dorm, President Trump announced travel restrictions on 26 European countries, including Spain. Although the 30-day travel ban did not apply to legal residents of the United States, Spain simultaneously imposed a nationwide lockdown to combat the virus. Madrid barred travel to and from the city, and word spread that international flights would soon be suspended. In the early hours of March 12, I was awoken to program directors frantically pounding on my door. They affirmed we had a mere 24 hours to escape Spain on the final flight to Atlanta.

I hastily packed clothes and souvenirs and boarded a bus to Madrid, leaving behind two suitcases full of belongings and many unsaid farewells to Spanish friends. After a five-hour excursion and many failed attempts to enter the city due to strict quarantine orders, I finally arrived at the Madrid-Barajas Airport. Panicked passengers in makeshift masks and hazmat suits rushed to their gates. Travelers emptied suitcases into trash cans to avoid long check-in lines. University students tearfully begged customer service for tickets home. While rushing through security, the customs officer reviewing my ticket murmured, “You’re lucky you found a flight out of here. Volver pronto,” meaning “come back soon.” On March 14, one day after my return to the United States, the Spanish Prime Minister, Pedro Sanchez, declared a state of emergency which placed the country on lockdown and cancelled all outgoing flights. I had narrowly escaped an impending two-month state of emergency.

On March 13th, travelers in hazmat suits rush through the Madrid-Barajas Airport. Photo by Shannon Moran.

Upon arrival in Atlanta, CDC workers recommended 14-day quarantine and randomly screened a handful of passengers for fevers. On April 20, Georgia Governor Kemp disregarded public health officials by announcing, “We will allow gyms, fitness centers, bowling alleys, barbers, cosmetologists, hair designers, nail care artists, estheticians, and massage therapists to reopen their doors.” Following a chaotic return to the United States and cancellation of my study abroad experience, I continue to fear contracting and spreading COVID-19 in a state reopening. In spite of dismay and uncertainty, I witnessed the world at a pivotal moment in history. Amidst a worldwide pandemic, I visited Europe’s cultural epicenters, and volveré pronto, I will return soon.

Shannon Moran

Shannon is a Journalism major at the University of Georgia, minoring in English and Spanish. As a fluent Spanish speaker, she is passionate about languages, cultural immersion and human rights activism. She has visited seven countries and thirty states and hopes to continue traveling the world in pursuit of compelling stories.

Alaska: The Problem of the Wilderness

An exerpt from “The Problem of the Wilderness” - Bob Marshall, 1930

“It is well to reflect that the wilderness furnishes perhaps the best opportunity for pure esthetic enjoyment. This requires that beauty be observed as a unity, and that for the brief duration of any pure esthetic experience the cognition of the observed object must completely fill the spectator’s cosmos. There can be no extraneous thoughts—no question about the creator of the phenomenon, its structure, what it resembles or what vanity in the beholder it gratifies. The purely esthetic observer has for the moment forgotten his own soul, he has only one sensation left and that is exquisiteness. In the wilderness, with its entire freedom from the manifestations of human will, that perfect objectivity which is essential for pure esthetic rapture can probably be achieved more readily than among any other forms of beauty.”

Kim Ludbrook / EPA

Coronavirus Shows We Are Not at All Prepared for the Security Threat of Climate Change

How might a single threat, even one deemed unlikely, spiral into an evolving global crisis which challenges the foundations of global security, economic stability and democratic governance, all in the matter of a few weeks?

My research on threats to national security, governance and geopolitics has focused on exactly this question, albeit with a focus on the disruptive potential of climate change, rather than a novel coronavirus. In recent work alongside intelligence and defence experts at the think-tank Center for Climate and Security, I analysed how future warming scenarios could disrupt security and governance worldwide throughout the 21st century. Our culminating report, A Security Threat Assessment of Global Climate Change, was launched in Washington just as the first coronavirus cases were spreading undetected across the US.

The analysis uses future scenarios to imagine how and where regions might be increasingly vulnerable to the resource, weather and economic shocks brought about by an increasingly destabilised climate. In it, we warn:

Even at scenarios of low warming, each region of the world will face severe risks to national and global security in the next three decades. Higher levels of warming will pose catastrophic, and likely irreversible, global security risks over the course of the 21st century.

Little did we know when writing these words and imagining the rapidly evolving shocks to come, that a very similar test of our global system was already brewing as governments sputtered to contain the damage of COVID-19.

Over the first few crucial weeks of this crisis, we’ve seen world leaders take a number of actions that indicate how climate shocks could destabilise the world order. With climate change disasters, as with infectious diseases, rapid response time and global coordination are of the essence. At this stage in the COVID-19 situation, there are three primary lessons for a climate-changing future: the immense challenge of global coordination during a crisis, the potential for authoritarian emergency responses, and the spiralling danger of compounding shocks.

An uncoordinated response

First, while the COVID-19 crisis has engendered a massive public response, governments have been largely uncoordinated in their efforts to manage the virus’s spread. According to Oxford’s COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, countries vary widely in the stringency of their policies, with no two countries implementing a synchronised course of action.

While traditionally a great power like the US might step forward to direct a collective international response, instead the Trump administration has repeatedly chosen to blindside its allies with the introduction of new limitations on trade and movement of peoples. This mismanagement has led to each nation going on its own, despite the fact that working together would net greater gains for all. As the New York Times’s Mark Landler put it, the voices of world leaders are forming “less a choir than a cacophony”, leading to mixed global messages, undetected spread, and ongoing fights over limited resources.

Politicians have sent mixed messages. Tasos Katopodis / EPA

In the face of climate change, such a lack of coordination could be be highly destabilising to world social and economic order. The mass displacement of people, the devaluation of assets, rising seas and natural disasters will call for shared practices and common decency in the face of continued tragedy. Many climate impacts will raise new questions the world has yet to answer. What do we do with nation-states that can no longer reside in their homeland? How do we compensate sectors for ceasing harmful practices such as fossil fuel extraction and deforestation, especially where national economies may depend on them?

We also face new global governance questions around the use of risky geoengineering technologies, which can be deployed unilaterally to alter local climates, but with the potential for vast unintended regional or even global consequences. These are challenges which, like climate change itself, can only be solved collectively through coordinated policies and clear communication. The sort of wayward responses and lack of leadership in response to COVID-19 would only lead to further destruction of livelihoods and order in the decades to come.

Authoritarian agendas

This historic moment is also offering new opportunities for leaders to further dangerous, illiberal agendas. Authoritarians have long used emergency situations as a pretext to further curtail individual rights and consolidate personal power against backdrops of real or imagined public danger. We’ve seen these actions spiral worldwide in the past month in autocracies and backsliding democracies, alike.

President Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines has given security services the directive to open fire on protestors while Vladimir Putin is deploying mass surveillance technologies and new criminal penalties to monitor the Russian population. Hungary’s prime minister Viktor Orbán has forced new emergency powers through parliament that muzzle political opposition and allow for his indefinite rule. Even the supposed democratic bastions of the US and the UK are seeing worrying signs of autocratic policies, as surveillance drones are deployed to monitor citizens, scientific expertise is undermined, and open-ended emergency powers are granted to police forces for undetermined time frames.

Police across the world have been given new powers. Yuri Kochetkov / EPA

A warming world will only result in more disaster-related events for power-hungry leaders to take advantage of in the years ahead. From the nationalisation of resources to the deployment of militaries in response to climate shocks, it can be all-too-easy for public safety needs to bleed into personal political opportunities. The second-order effects of climate change, from supply chain instability to the migration of peoples, will also provide authoritarian leaders more fodder for their ethno-nationalist ideologies, which inflame divisions in society and could help broaden their personal appeal. Without clear and sturdy limits on executive power, the disruptive impacts of climate change will be used to further chip away at democratic freedoms across the world.

Overlapping shocks are the new normal

Finally, this situation is teaching the globalised world new lessons on the devastating consequences of compounding shocks. Managing a deadly global pandemic is bad enough, even before you layer on the massive unemployment, trade disruptions and economic shutdown that its mitigation sets in motion.

The months ahead will bring about additional crises – some related to the pandemic, like a massive uptick in public debt used to bail out national economies. But other near-term shocks may themselves be climate change-induced, from new forecasts for large-scale floods this spring in the central US, to a prospective repeat of 2019’s severe summer heat waves across Europe.

Recent floods in Mosul, Iraq. Can we handle climate-related disasters during a pandemic? Ammar Salih / EPA

These disasters have the potential to strike just at the time when people are being advised to shelter inside, many in at-risk areas and without adequate indoor cooling. Overlapping, historic shocks like this are becoming the new normal in our climate-changed era. As public disaster response budgets spiral and loss of life mounts each year, governments will continue to struggle to contain their compounding damage.

Scientists and security professionals alike have long warned about the devastating potential of climate change, alluding to how it might rattle our global governance systems to breaking point. But few could have expected that the fissures in our institutions would be revealed so soon, let alone on such a disturbingly large scale.

We can treat the current global crisis as a sort of “stress test” on these institutions, exposing their vulnerabilities but also providing the urgent impetus to build new resilience. In that light, we could successfully rebound from this moment with more solid global security and cooperation than we knew going into it. Decision-makers should take a hard look at their current responses, problem-solving methods, and institutional design with future climate forecasts like our Threat Assessment in mind.

We know that even steeper and more frequent global shocks are in store, particularly without serious climate change mitigation efforts. What we don’t yet know is whether we’ll repeat current patterns of mismanagement and abuse, or if we’ll chart a more proactive and resilient course through the risks that lie ahead.

Kate Guy PhD Candidate and Lecturer in International Relations, University of Oxford

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Divyakant Solanki/EPA

In India’s Cities, Life is Lived on the Streets – How Coronavirus Changed That

In India, where the coronavirus lockdown affects 1.3 billion people, the effect is a big contrast to a place where the city streets are normally thronged with life in all its guises.

Read MoreBloom: Japan

In April this year, director Julian Lucas went on holiday to Japan - his camera came with him.

The result is the film Bloom.

He discovered a peculiar sense of quiet, desolation, and loneliness among the people.

In a country so packed with lights and trains and crowds and experiences, from the theatrical to the serene to patently bizarre, Bloom captures this lovely dichotomy between the people and the cities they inhabit. Inside the noise and the chaos, Julian captures people alone, wandering the streets, buried in telephones - a dull, menacing and peaceful nothingness below the surface.

What’s most inspiring about the footage is the way that it doesn’t struggle or form its way into any kind of narrative - Julian just lets the film be exactly what it is. But in that loose process, which is unlikely an accident, there’s this dizzying repetition that tells us something quite profound about Japanese culture. The score, too, by Matt Hadley, dances with the vision. At times intense and jarring, edited cleverly to interplay with the captured audio. At times serene and beautiful, with layered synths and string lines that dance softly up and down the keyboard.

“I wanted the soundtrack to be it's own character,” says Julian. “I wanted the viewer to be as audibly stimulated as they are visually. And I wanted sounds from the real world to contribute to the rhythm and pacing of the piece.”

LOCKDOWN: Edinburgh, Scotland

“The COVID-19 pandemic has affected many people’s lives all over the world. This short film is focusing solely on Edinburgh, showcasing the situation and how the daily lives in the city have been affected. Inclusion of some positivity and optimism too in this short film. My own old stock footage as well as some aerial footage from other sources were used. New current footage were shot without flouting the lockdown rules, only done so in conjunction with essential travel.” Carsan Choong

An urban street in Bangladesh. Manbarlett. CC 2.0

The Detrimental Impact of Covid-19 on Developing Nations

The world has dealt with COVID-19 since the beginning of the year with varying countries successfully staving it off. However, the question of how developing countries are doing has crossed the media only a few times. The problem is our inability to know the true extent of their situation since they do not have the same means as more developed countries like ourselves and other impacted countries. Their economic situations are close to being called a crisis while medical care is scarce to come by. In countries like Bangladesh, Nigeria and South Africa, their vulnerability to the virus has increased with the global economic shut-down and sparse supplies.

The Economic Crisis

The biggest issue with developing countries is their reliance on “foreign income and tourism”. This ultimately means that regardless of confirmed COVID-19 cases, they will feel the impact of the virus as the world economy faces major setbacks and in some cases come close to halting as some countries' exports are affected. For example, in Bangladesh “only 15% of Bangladeshi workers make over $6 a day”, meaning very few families are able to support themselves in the event of an economic shut down. The World Bank has sent aid across the globe and plans to send out close to $160 billion dollars of relief money to Africa and countries such as Pakistan, India, Ethiopia and more, hoping to help relieve them of economic stress and strengthen “their national health systems.” An issue that has risen with giving aid to these countries is that their situation is not like the United States of America where we can enforce “social distancing guidelines and then pair them with stimulus packages”. Poorer countries, such as Bangladesh, are more spread out with the majority of their population self-employed or working in informal sectors meaning they are not under the tax and benefits system. They tend to live “hand-to-mouth” instead of pay-check to paycheck. This means they are completely reliant on what they make that day to feed their families and survive. Further complicating the matter, with so few resources spread out across the country, we are unable to find the COVID-19 epicenters of these countries. They lack the proper test kits and quantity, resulting in an inaccurate number of positive COVID-19 cases and too few resources for help and trained professionals.

The Impact on Medical Care

It has been predicted that with the rest of the world’s cases slowly dropping, the new world epicenter for COVID-19 will shift to Africa. Currently, they have “10,000 reported confirmed cases and over 500 fatalities”. While they were not the first to be impacted, their curve of cases has yet to flatten, worrying health officials worldwide. Just this last week, Capetown, South Africa jumped 43% with confirmed cases, alerting the WHO of the rising crisis but no way to determine the true epicenter of the continent. Without proper safety equipment in hospitals, many doctors or nurses try to avoid seeing patients who predict they have the virus, seeing as they won’t be protected themselves. Additionally, there is a severe lack of testing kits available, so they’ve tried to spread them out as much as possible nationwide. A stark example is Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country with over 200 million inhabitants, which has reported almost 900 COVID-19 cases with only 28 confirmed deaths. They have only conducted just over 7,000 tests with only 5,000 of these coming in this past week and being used. This lack of equipment again adds to the ignorance of the true numbers of cases these countries have and how we can help.

Lastly, countries such as South Africa and Bangladesh have an inability to obtain an adequate amount of medical supplies, and the ones they do have are spread so thin that they are hardly useful. Populations are scrambling to seek help, but social-distancing guidelines like we’ve seen in our own country are impossible to implement in countries where most of their population do not live in an urban setting. For example, in Bangladesh, the entire country only has “432 ICU beds with only 110 outside the capital city of Dhaka”. This ultimately means unless the Bangladeshi population lives inside the city, it’s unlikely they will receive the help they need. Already Bangladesh has over 5,000 confirmed cases and over 150 deaths. Their inability to give out adequate healthcare has required donations from all around the world to enable people to get the help they need. Bangladesh, Nigeria and South Africa are only a few examples of the countries who rely on each other to take home food and money to their families, and most do not live in a country that has an organized, official census. This makes it hard for health officials to know how much supplies they need to send to these countries and give them aid.

Implemented Strategies

Initially, their ability to sustain their countries through this pandemic has looked grim, but the world has flooded in to help by donating supplies and tests. For example, in Bangladesh, officials have implemented a survey to try to get a good grasp on the exact number of population while increasing their efforts to educate the general population on what COVID-19 is and how to keep themselves safe. Additionally, they are working on an already established census to call citizens to check in on them, making sure they have the help and resources they need. In other countries like South America and Nigeria, they are currently working on educating their populations and trying to implement as little contact as possible with people not related to each other. At the end of the day, the most that can be done is a step by step process that starts with getting the full scope of what these countries are dealing with. This starts with getting more test kits sent out and more government officials working on getting the exact numbers on a population.

Ultimately, the world has been floored by this pandemic, and each day brings a new challenge. But globally, people are gathering to find ways to help countries who are not as equipped to function as normal, while ensuring the safety of everyone is kept at the forefront of their minds.

Elizabeth Misnick

is a Professional Writing and Rhetoric major at Baylor University. She grew up in a military family and lived in Europe for almost half her life, traveling and living in different countries. She hopes to continue writing professionally throughout her career and publish her writing in the future.

Child Adoption by Nick Youngson CC BY-SA 3.0 Alpha Stock Images

Adoption in the Time of Covid-19

The coronavirus has created new challenges and caused disruptions for child adoptions and surrogacy as adoption-related travel has been delayed and U.S. courts were closed for nonessential hearings. On April 22, 2020 President Trump signed an executive order that restricted immigration into the U.S. for the next 60 days due to the COVID-19 outbreak. Adoptive families were concerned about how the order would impact them and their prospective children. Holt International, a nonprofit, faith-based adoption agency received an official notice that “children can still travel home to the U.S. with their adoptive families, and international adoptions can move forward without delay.” While this is a relief for American adoptive families, it is only one of the hurdles families faced as the coronavirus has complicated international and domestic adoption, as well as surrogacy.

International Adoption

From 1999 to 2019, 275,891 international children were adopted by families in the U.S, according to data from the U.S. Department of State. Children from China, Russia, Guatemala, South Korea, and Ethiopia accounted for 71% of all international adoptions to the U.S. since 1999, according to a 2017 study by the Pew Research Center. In early February 2020 the State Department suspended visas to China, effectively banning travel to China because of COVID-19. As the coronavirus continued to spread, the U.S. restricted travel from Europe, effective March 13, 2020. With the travel bans in effect, American families who were in the process of adopting internationally had their plans delayed, some without a timeline due to the uncertainty around when shelter-in-place orders and the travel bans will be lifted.

According to NPR, Chinese regulations state that adoptions must be completed before a child turns 14. In addition, adoptions from China take about one to two years to be finalized, according to America World Adoption. With the added delays of the coronavirus, NPR says this means that “some of those children are in jeopardy of aging out of the adoption system forever.”

Domestic Adoption

According to statistics from the Adoption Network, around 140,000 American children are adopted in the U.S. each year. Although the coronavirus has altered daily life and has made adoption more difficult, child welfare agencies are finding ways to continue domestic adoptions despite canceled court hearings. Agencies like the National Court Appointed Special Advocate and the Department of Children and Family Services have turned to technology to proceed with adoption hearings.

A Pennsylvania family was able to adopt their 7-year-old son Dominic over a conference call on April 6. Two families in Louisiana completed their adoption ceremonies over the phone on April 7. On April 16 in Arkansas, 2-year-old Jaden’s adoption hearing took place over a Zoom video call. Although families are not physically able to have their official adoption ceremonies, they are not letting that dampen their joy of adding a new addition to the family.

Surrogacy

While the travel restrictions have not affected some international adoptions, they have greatly affected surrogacy. The Washington Post reported that many people overseas with surrogates in the U.S. are either unable to enter the country or are stuck in the U.S. and unable to bring their newborns home. Since the U.S. government has put a hold on most routine passport services unless it is a life-or-death emergency, families whose newborn babies were born to gestational surrogates are unable to obtain a passport for their infant. Without a passport, parents cannot take their newborn home. According to NBC, that delay can cost parents around $20,000, on top of the staggering cost of surrogacy.

Asiya Haouchine

is an Algerian-American writer who graduated from the University of Connecticut in May 2016, earning a BA in journalism and English. She was an editorial intern and contributing writer for Warscapes magazine and the online/blog editor for Long River Review. She is currently studying for her Master’s in Library and Information Science. @AsiyaHaou

Explore Georgia’s Martvili Canyon

There was a time when the exquisite blue-green waters of Martvili Canyon were only open to Georgian nobles, who would visit to bathe. Now, everyone is welcome to boat and swim here. The picturesque natural wonder is located in Samegrelo, a coastal region of Georgia known for being a historical center of the country’s cuisine and culture. The two-level canyon is thick with moss and other plant life and dotted with waterfalls and caves. And even on the hottest days of summer, the water that pools in the lower level of the canyon is refreshingly cool.

This Great Big Story is by Georgia National Tourism Administration.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON GREAT BIG STORY

‘Today, the pond. Tomorrow, the world!’ Patrick Robert Doyle/Unsplash, CC BY-SA

Coronavirus: What the Lockdown Could Mean for Urban Wildlife

As quarantine measures take hold across the world, our towns and cities are falling silent. With most people indoors, the usual din of human voices and traffic is being replaced by an eerie, empty calm. The wildlife we share our concrete jungles with are noticing, and responding.

You’ve probably seen posts on social media about animals being more visible in urban centres. Animals that live in cities or on their outskirts are exploring the empty streets, like the Kashmiri goats in Llandudno, Wales. Others that would normally only venture out at night are becoming bolder and exploring during the daytime, like the wild boar in Barcelona, Spain.

Our new habits are altering the urban environment in ways that are likely to be both positive and negative for nature. So which species are likely to prosper and which are likely to struggle?

Hooray for hedgehogs

It’s important to note some species may be unaffected by the lockdown. As it coincides with spring in the northern hemisphere, trees will still bud and flower and frogs will continue to fill garden ponds with frog spawn. But other species will be noticing our absence.

The way we affect wildlife is complex, and some of the changes that we’ll see are hard to predict, but we can make some assumptions. In the UK, hedgehogs are our most popular mammal, but their numbers are in rapid decline. There are many reasons for this, but many die on roads after being hit by cars. With people being asked to only make essential journeys, we are already seeing reduced road traffic. Our spiny friends will have just emerged from hibernation and will no doubt be grateful for the change.

The lockdown could be well timed for hedgehogs emerging from hibernation. Besarab Serhii/Shutterstock

Cities are also noisy places, and the noise affects how different species communicate with each other. Birds have to sing louder and at a higher pitch than their rural counterparts, which affects the perceived quality of their songs. With reduced traffic noise, we could see differences in how bats, birds and other animals communicate, perhaps offering better mating opportunities.

School closures may not be ideal for working parents, but many will use their time to connect with nature in their own backyard. More time spent in gardens (for those lucky enough to have one), perhaps doing activities like making bird feeders, could help encourage nature close to home. There’s been a surge in people taking part in citizen science projects like the Big Butterfly Count too. These help scientists to predict the population trends of different species. The British Trust for Ornithology has just made participation in their Garden BirdWatch Project free during the lockdown, so you can connect with wildlife and contribute to important scientific research.

Desolation for ducks

All is not rosy for wildlife. Many species currently rely on food provided by humans. From primates fed by tourists in Thailand, to the ducks and geese at local parks which have been closed to the public, many animals may be seeking new sources of food.

In the UK, the bird breeding season has already begun for earlier breeders like robins. Depending on how long restrictions last, many birds could ultimately make bad decisions about where to breed, assuming their carefully chosen spot is always rarely disturbed. This could threaten rarer birds which breed in the UK, such as little terns, as dog walkers and other people flock to beaches once restrictions are lifted, potentially trampling and disturbing breeding pairs and their young.

A little tern sheltering eggs on an open beach. BOONCHUAY PROMJIAM/Shutterstock

Dog walkers also enjoy lowland heathlands, especially those near urban areas such as Chobham Common in Surrey. These rare heaths are home to many rare bird species, like Dartford warblers, which could also see their nests disturbed once humans begin to emerge again in larger numbers. People who are enthralled by wildlife venturing into new areas during lockdown will need to carefully manage their return to the outdoors once restrictions are lifted.

Though some species may face challenges in now silent towns and cities, those species that live alongside us do so because they are so adaptable. They will find new sources of food, and will exploit new opportunities created in our absence. Hopefully this time will allow people to appreciate their local environments more, and find new ways to nurture them once all this is over.

Becky Thomas: Senior Teaching Fellow in Ecology, Royal Holloway

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Quarantine Brainstorm

Adriano Maffei Scatimburgo offers us a chance to experience the freedom of travel even as we ficar em casa, stay at home.

Calais Refugee Camp. Michal Bělka. C.C.4.0

Coronavirus in Calais: the Effect of COVID-19 on Refugees

The repercussions of Coronavirus are being felt across the whole world. But the degree to which they are felt greatly depends on social and economic status. Refugees are one of the groups facing the most severe effects of the virus. And in Calais, the vulnerable conditions are in full display.

Calais is a port city situated at the narrowest point of the English Channel, making it the closest French city to England. Because of this proximity to England, it is a major stopping point for refugees and migrants on their way to the United Kingdom. This has led to many encampments being made in the city, most notably the “Calais Jungle,” which gained international attention due to its population of nearly 10,000 during the European migrant crisis.

Following the clearing of the camp, the French government addressed a no tolerance speech to the refugees in Calais. They would continue to pass through Calais, but faced constant force from local authorities.

Today, their situation has devolved considerably. As of April 21, France has reported 120,000 cases and 20,000 deaths. The Hauts-de-France region, where Calais is located, has 4,000 cases. As of early April, 1,000 refugees and migrants are left without access to proper sanitation, water, or food. The number in one camp went from two to nine in three days. When in such dire circumstances, social distancing is not a possibility. Beyond this, their lack of access to basic resources, along with the intense stress of daily life, ensures that their immune systems are weak.

The organizations helping the migrants have been forced to suspend their activities due to the virus, leaving them without access to hot food. Now, without the means to acquire the declaration forms needed to leave home, they do not have the means to go to supermarkets. Instead, migrants are reliant on food packs given by local authorities: a piece of bread, cheese, and butter.

Their camps are continuing to be cleared and they are being sent to accommodation centers.

The buses used to escort the refugees do not have enough space to maintain social distancing, and are only able to carry 30 people every two days, a pace criticized for being too slow.

The transfers are said to be voluntary, but after facing consistent force from police, most migrants do not trust the authorities. Many migrants would rather cross the Channel to England than find out what accommodation center life is like. The number of channel crossing attempts has surged due to Coronavirus. This is an incredibly dangerous journey made on inflatable boats, that refugees are willing to risk making just to avoid both French authorities and the dire conditions of the camps.

For migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees in Calais, COVID-19 is not the greatest threat. It is simply another threat, another obstacle to surviving and starting a new life. Across the world, vulnerable peoples now face even greater risks due to the virus.

Arlo O’Blaney

grew up in New York City. He is currently a sophomore human rights major at Bard College. He intends on using this background to pursue a job in journalism or law.

Farmers in Northern Thailand, tbSMITH, CC 2.0

Thailand Combats Drought and Choking Fires While Still Dealing with COVID-19

Thailand has been hit on many ends this year it seems while combating COVID-19, fighting the worst drought they’ve seen for over 40 years and citizens pointing fingers on the origins of the northern fires that have devastated the country. The internal divisions of the country have only increased with everyone on edge because of these events. Already they’ve had to cancel Songkran, a two-day annual festival for Thai New Year on April 13th. The national water festival has always brought the nation together and is thrown to celebrate change. It usually consists of “spraying water guns and hurling water off pick-up trucks in a free-for-all water fight”, but has now been cancelled due to the global pandemic that has devastated the globe. With over half of Thailand’s COVID-19 cases originating from Bangkok, curfews, quarantines and cancellations have been implemented to keep their citizens safe during this time.

The Environmental Toll

Even worrying still, Thailand has been combatting a drought that started in the middle of last year and has been “forecast to last until July”. Many villages have already declared that they have been impacted by the drought, and with dams only “49% full” and only “26% percent can actually be used” for drinking water and agriculture Thailand has faced a significant drop in the global market as their crops are impacted. The dams especially are impacted by the river being dammed upstream in China, stopping the rivers from flowing as normal and decreasing their ability to grow their crops. Thailand is one of the world’s main exporters of sugar, rice and rubber, but it’s now expected to “decrease over 30%”, especially with Thailand being “the world’s second largest sugar exporter” which has directly impacted the global price of sugar per pound. This has been adding even more pressure to the Prayut government who have been struggling to keep the peace between “Thais living in villages and cities of the north and leaders of Bangkok” due to the fires that have started in Northern Thailand and some stating they think it to be deliberately set. These fires have caused significant damage to air quality, and at least three villagers who have died in separate events related to the forest fires, though some have stated that “the number of lives lost in the recent blazes is higher than the official toll.” Tensions are high and with a country already at a level of distrust with one another, the government is fighting to keep the thin peace that is being held.

COVID-19’s Toll on Thai Economy

Domesticated Thai Elephants, magnetisch, CC 2.0

Amazingly, for the “third day in a row, Thailand has reported no new deaths”. This means that their current efforts to quell the number of cases has worked, even if they were slower to react to the virus and implement screenings, quarantines and curfews. However, while it seems Thailand has found a handle on the virus and contact-tracing, the new COVID-19 laws have meant significant decrease in tourism. Around the country, there are about “4,000 domesticated elephants which visitors pay to trek with” but with the new pandemic guidelines, these parks have been closed, meaning park owners won’t be able to accurately feed their animals. Concerns for the elephants starving have started to increase, while the government has eyes on Thailand’s economy decreasing over 30% in light of their drought. Ultimately, it has been speculated that this will be “Thailand’s worst in more than a decade.”

The last year and a half has seen Thailand take one hit after another in regards to their environment, citizen health and economy. The world is scrambling to keep control of their countries, and like the rest, the Thai government is working night and day to try to keep their citizens paid, healthy, and still maintain trust after closing their borders to international travel and implementing new guidelines.

Elizabeth Misnick

is a Professional Writing and Rhetoric major at Baylor University. She grew up in a military family and lived in Europe for almost half her life, traveling and living in different countries. She hopes to continue writing professionally throughout her career and publish her writing in the future.

View from N. Seoul Tower. Goggins World. CC 2.0

How South Korea has Successfully Controlled COVID-19 and Why We Should Learn from Them

The question of why some countries have been more successful than others with their response to the current global pandemic has been asked more frequently as COVID-19 becomes a household term. In recent months, the illness has sent the world scrambling, with some slower to react than others, causing a detrimental increase in confirmed cases popping up globally. One country has seen it all and now see a decrease in their cases without shutting down the entire country. Interestingly one of the closest countries to the point of the first initial outbreak, South Korea has baffled the world in their ability to quell the spread of virus and control it. Confirming up to “30 new cases a day, while in the UK it’s about 5,000, and the US it’s more than 20,000.”, South Korea is among the top four countries in the world to have “controlled” the spread of the virus. But how has South Korea done it?

Speed

Before their first case was confirmed within their borders, South Korea had already started to quarantine and screen people arriving from Wuhan, China. This started on January third, “more than two weeks before the country’s first infection was even confirmed.” Once Korea caught wind of an outbreak, they were quick to start putting safety measures in place, ensuring that they could do all they could to keep it out. Like Dr. Eom Joong Sik stated to CNN in an interview, “early diagnosis, early quarantine and early treatment are key.” South Korea understood from the get-go that the speed in which they responded directly correlated to the amount of cases they would receive.

Innovation

South Korea still stands as one of the world’s leading centers of technology and innovation. Once they found out about COVID-19, they started to quarantine their residents and utilize two major factors. The first was a sort of “drive-through” screening process to get people tested, a model the United States has now implemented in several states. They have “tested more than 500,000 people, among the highest in the world per capita”, as well as going through rigorous contact-tracing. This has resulted in “fewer than one in every 100,000 people in South Korea’s population” dying from the virus. Additionally, they have utilized an app on the population’s phones to keep tabs on them while in quarantine, ensuring that they’re safe and healthy at home.

Learning from the Past

The question to why was South Korea so prepared for this global pandemic is answered simply: they learned from the past. In 2015, the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome shocked the world and South Korea “recorded 186 cases and 38 deaths, making it the worst impacted country outside of the Middle East”. They took the lessons of what devastated their country before and worked to ensure they had safety measures in place in case something like that were ever to hit their country again.

If you’re looking for models to emulate to stay safe from the virus, then looking at South Korea is a sure-way to help. You can never take safety too seriously. Stay inside, follow guidelines and watch our own cases drop as we pass peak periods and continue distancing ourselves until the world is safe for us once again.

Elizabeth Misnick

is a Professional Writing and Rhetoric major at Baylor University. She grew up in a military family and lived in Europe for almost half her life, traveling and living in different countries. She hopes to continue writing professionally throughout her career and publish her writing in the future.

“Uighur Women” by Sean Chiu is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

The Coronavirus Brings Added Concern For Uighur Muslims

More than 200,000 Uigher Muslims from northwest China have been forced into re-education camps (akin to concentration camps), where they experience forced labor, political indoctrination and even torture. These groups are now at high risk for Covid-19 due to overcrowding and poor ventilation in the camps.

Read MoreLockdown Lessons From the History of Solitude

When the poet John Donne was struck down by a sudden infection in 1623 he immediately found himself alone – even his doctors deserted him. The experience, which only lasted a week, was intolerable. He later wrote: “As sickness is the greatest misery, so the greatest misery of sickness is solitude.”

It’s hard to believe now, but until relatively recently, solitude – or the experience of being alone for significant periods of time – was treated with a mixture of fear and respect. It tended to be restricted to enclosed religious orders and was thus a privileged experience of a male elite. Change was only set in motion by the Reformation and the Enlightenment, when the ideologies of humanism and realism took hold and solitude slowly became something that anyone could acceptably seek from time to time. Most people in the West are now used to some regular form of solitude – but the reality of lockdown is making this experience far more extreme.

I have spent the last few years researching the history of solitude, looking into how people in the past managed to balance community ties and solitary behaviours. This has never seemed more relevant.

Take the example of my own community. I live – and now work – in an old house in an ancient Shropshire village in England. In the 11th-century Domesday Book it was recorded as a viable community, on a bluff of land above the River Severn. Over the centuries, its self-sufficiency has declined. Now it has no services beyond the church on Sunday.

But it has long displayed a collective spirit, mostly for seasonal entertainment and the maintenance of a village green, which contains the ruins of a castle built to keep the Welsh in Wales. Planning was taking place for a formal ball in a marquee on the green this autumn, which has yet to be cancelled. In the meantime, the Neighbourhood Watch group, in place to deal with very rare criminal activity, has delivered a card to all residents, offering to help with “picking up shopping, posting mail, collecting newspapers, or with urgent supplies”. There is a WhatsApp group where many locals are offering support.

For the first time in generations, the attention of the inhabitants is not focused on the resources of the region’s urban centres. The nearby A5, the trunk road from London to Holyhead and thence to Ireland, no longer goes anywhere important. Instead, the community has turned inwards, to local needs, and the capacity of local resources to meet them.

This experience of a small British settlement reflects the condition of many in Western societies. The COVID-19 crisis has led us to embrace new technologies to revitalise old social networks. As we begin to come to terms with the lockdown, it is important to understand the resources at our disposal for coping with enforced isolation.

History can assist with that task. It can give a sense of perspective on the experience of being alone. Solitude has only become a widespread and valued condition in the recent past. This gives some support to our capacity to endure the COVID-19 lockdown. At the same time, loneliness, which can be seen as failed solitude, may become a more serious threat to physical and mental well-being. That failure can be a state of mind, but more often is a consequence of social or institutional malfunctions over which the individual has little or no control.

Desert fathers

At the beginning of the modern era, solitude was treated with a mixture of exaggerated respect and deep apprehension. Those who withdrew from society imitated the example of the fourth-century desert fathers who sought spiritual communion in the wilderness.

St Anthony the Great, for example, who was made famous in a biography by St Athanasius around the year 360 CE, gave away his inheritance and retreated into isolation near the the River Nile, where he lived a long life subsisting on a meagre diet and devoting his days to prayer. Whether they sought a literal or metaphorical desert, the solitude of St Anthony and his successors appealed to those seeking a peace of mind that they could no longer locate in the commercial fray.

The Meeting of St Anthony and St Paul, Master of the Osservanza, c. 1430-1435. Wikimedia Commons

As such, solitude was conceived within the frame of a particular Christian tradition. The desert fathers had a profound influence on the early church. They conducted a wordless communion with a silent God, separating themselves from the noise and corruption of urban society. Their example was institutionalised in monasteries which sought to combine individual meditation with a structure of routine and authority that would protect practitioners from mental collapse or spiritual deviation.

In society more broadly, the practice of retreat was considered suitable only for educated men who sought a refuge from the corrupting pressures of an urbanising civilisation. Solitude was an opportunity, as the Swiss doctor and writer Johann Zimmermann, put it, for “self-collection and freedom”.

Women and the less well-born, however, could not be trusted with their own company. They were seen to be vulnerable to unproductive idleness or destructive forms of melancholy. (Nuns were an exception to this rule, but so disregarded that the 1829 Catholic Emancipation Act, which specifically criminalised monks and monasteries, did not mention convents at all.)

But over time, the risk register of solitude has altered. What was once the practice of enclosed religious orders and the privileged experience of a male elite has become accessible to almost everyone at some stage in their lives. This was set in motion by the twin events of the Reformation and the Enlightenment.

A social god

Attitudes were changing by the time Donne, poet and Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral, was struck down by that sudden infection and deserted by all and sundry. He wrote that the instinctive response of the healthy to the afflicted did nothing except increase his suffering: “When I am but sick, and might infect, they have no remedy but their absence and my solitude.” But he found solace in a particularly Protestant conception of God. He saw the supreme being as fundamentally social:

There is a plurality of persons in God, though there be but one God; and all his external actions testify a love of society, and communion. In heaven there are orders of angels, and armies of martyrs, and in that house many mansions; in earth, families, cities, churches, colleges, all plural things.

This sense of the importance of community was at the heart of Donne’s philosophy. In Meditation 17, he went on to write the most famous statement of man’s social identity in the English language: “No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.”

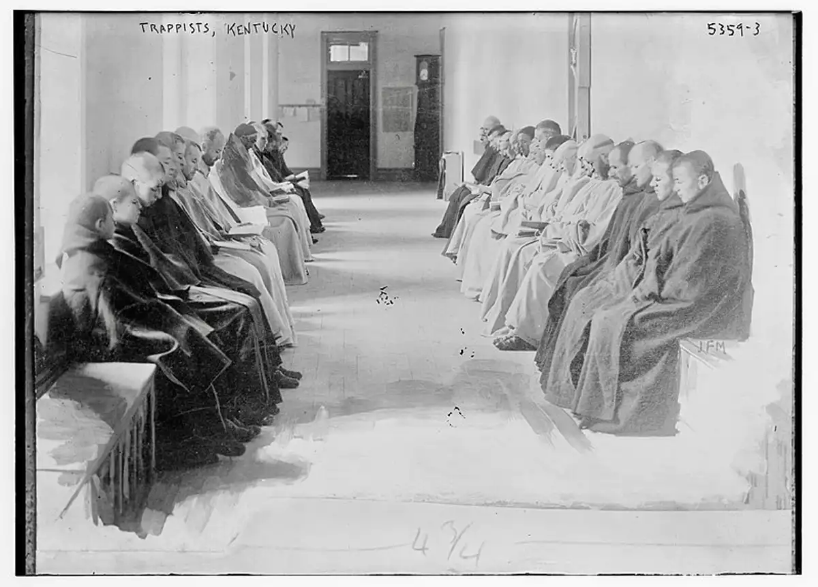

In the Catholic church, the tradition of monastic seclusion was still the subject of periodic renewals, most notably in this era with the founding of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance, more commonly known as the Trappists, in 1664 France. Within the walls of the monastery, speech was reduced to an absolute minimum to allow the penitent monks the greatest opportunity for silent prayer.An elaborate sign language was deployed to enable the monks to go about their daily business.

Trappists in Kentucky. Library of Congress, CC BY-SA

But in Britain, the work of Thomas Cromwell had devastated the enclosed orders, and the tradition of spiritual withdrawal was pushed to the margins of religious observance.

In the era following Donne’s time of anguish, the Enlightenment further emphasised the value of sociability. Personal interaction was held to be the key to innovation and creativity. Conversation, correspondence and exchanges within and between centres of population, challenged structures of inherited superstition and ignorance and drove forward inquiry and material progress.

There might be a need for withdrawal to the closet for spiritual meditation or sustained intellectual endeavour, but only as a means of better preparing the individual for participation in the progress of society. Prolonged, irreversible solitude began to be seen essentially as a pathology, a cause or a consequence of melancholy.

The spread of solitude

Towards the end of the 18th century, a reaction to this sociability set in. More attention began to be paid, even in Protestant societies, to the hermit tradition within Christianity.

The Romantic movement placed emphasis on the restorative powers of nature, which were best encountered on solitary walks. The writer Thomas De Quincey calculated that in his lifetime William Wordsworth strode 180,000 miles across England and Europe on indifferent legs. Amidst the noise and pollution of urbanising societies, periodic retreat and isolation became more attractive. Solitude, providing it was embraced freely, could restore spiritual energies and revive a moral perspective corrupted by unbridled capitalism.

At a more everyday level, improvements in housing conditions, domestic consumption and mass communication widened access to solitary activities. Improved postal services, followed by electronic and eventually digital systems, enabled men and women to be physically alone, yet in company.

Increasing surplus income was devoted to a widening range of pastimes and hobbies which might be practised apart from others. Handicrafts, needlework, stamp-collecting, DIY, reading, animal and bird breeding, and, in the open air, gardening and angling, absorbed time, attention and money. Specialised rooms in middle-class homes multiplied, allowing family members to spend more of their time going about their private business.

Increased incomes gave rise to more time for hobbies, such as building collections. Manfred Heyde/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

And although monasteries had been explicitly excluded from the epochal Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, Britain subsequently witnessed a bitterly contested revival of enclosed orders of both men and women.

By the early 20th century, declining family size combined with council houses began to supply working-class parents and children with domestic spaces of their own. Electric light and central heating meant that it was no longer necessary to crowd around the only source of warmth in the home. Slum clearances emptied the streets of jostling crowds, and adolescent children began to enjoy the privilege of their own bedroom.

In middle-class homes, domestic appliances replaced live-in servants, leaving the housewife, for good or ill, with her own society for much of the day. The motor car, the aspiration of the middle class between the wars, and increasingly the whole of the population in the second half of the 20th century, provided personalised transport, accompanied by privately-chosen radio and later musical entertainment.

Self-isolating society

After 1945, society more broadly began to self-isolate. Single-person households, a rare occurrence in earlier centuries, became both feasible and desirable. In our own times, nearly a third of UK residential units have only one occupant. The proportion is higher in parts of the US and even more so in Sweden and Japan.

The widowed elderly, equipped for the first time with adequate pensions, can now enjoy domestic independence instead of moving in with children. Younger cohorts can escape unsatisfactory relationships by finding their own accommodation. Around them a set of expectations and resources have developed, making solitary living both a practical and a practised way of life.

Living by yourself, for shorter or longer periods, is itself no longer seen as a threat to physical or psychological well-being. Instead, concern is increasingly centred on the experience of loneliness, which in Britain led to the appointment of the world’s first loneliness minister in 2018, and the subsequent publication of an ambitious government strategy to combat the condition. The problem is not being without company itself, but rather, as writer and social activist Stephanie Dowrick puts it, being “uncomfortably alone without someone”.

More and more people live alone. Chuttersnap/Unsplash, FAL

In late modernity, loneliness has been less of a problem than campaigners have often claimed. Given the rapid rise both of single-person households and the numbers of elderly people, the question is not why the incidence has been so great but rather, in terms of official statistics, why it has been so small.

Nonetheless, the official injunction to withdraw from social gatherings in response to the escalating threat of the COVID-19 pandemic throws renewed attention on the often fragile boundary between life-enhancing and soul-destroying forms of solitary behaviour. This is not the first time governments have attempted to impose social isolation in a medical crisis – quarantines were also introduced in response to the medieval plague outbreaks – but it may be the first time they fully succeed. No one can be sure of the consequences.

The threat of isolation

So we should take comfort from the recent history of solitude. It is certain that modern societies are much better equipped than those in the past to meet such a challenge. Long before the current crisis, society in much of the West moved indoors.

In normal times, walk down any suburban street outside the commute to work or school, and the overriding impression is the absence of people. The post-war growth of single-person households has normalised a host of conventions and activities associated with the absence of company. Homes have more heated and lighted space; food, whether as raw materials or takeaway meals, can be ordered and delivered without leaving the front door; digital devices provide entertainment and enable contact with family and friends; gardens supply enclosed fresh air to those who have one (now made still fresher by the temporary absence of traffic).

By contrast, the pattern of living in Victorian and early 20th-century Britain would have made such isolation impossible for much of the population. In working-class homes, parents and children passed their days in a single living room and shared beds at night. Lack of space continually forced occupants out into the street where they mixed with neighbours, tradesmen and passers-by. In more prosperous households, there were more specialised rooms, but servants moved constantly between family members, ran errands to the shops, dealt with deliveries of goods and services.

The history of solitude should also encourage us to consider the boundary between solitude and loneliness – because it is partly a matter of free will. Single-person households have expanded in recent times because a range of material changes made it possible for young and old to choose how they lived. At the opposite end of the spectrum, the most extreme form of modern solitude, penal solitary confinement wreaks destruction on almost everyone exposed to it.

Loneliness, Hans Thoma, 1880. National Museum in Warsaw, Wikimedia Commons

Much will now depend on whether the state engenders a spirit of enlightened consent, whereby citizens agree to disrupt their patterns of living for the sake of their own and the common good. Trust and communication police the boundary of acceptable and unacceptable isolation.

It is a matter of time. Many of the forms of solitude which are now embraced are framed moments before social intercourse is resumed. Walking the dog for half an hour, engaging in mindful meditation in a lunch break, digging the garden in the evening, or withdrawing from the noise of the household to read a book or text a friend are all critical but transient forms of escape.

Those living alone experience longer periods of silence, but until lockdown was imposed, were free to leave their home to seek company, even if only in the form of work colleagues. Loneliness can be viewed as solitude that lasts too long. For all the science driving current government policy, we have no way of knowing the cost to people’s peace of mind of isolation that continues for months on end.

We must remember that loneliness is not caused by living alone itself, but the inability to make contact when the need arises. Small acts of kindness between neighbours and support from local charities will make a great difference.

There is an expectation that, for good or ill, the experience of the COVID-19 epidemic will be standardised. Outside the lottery of infection, most will endure the same constraints on movement, and, through quasi-wartime financial measures, enjoy at least the same basic standard of living. But by circumstance or temperament, some will flourish better than others.

More broadly, poverty and declining public services have made it much more difficult to gain access to collective facilities. Last-minute funding changes by government will struggle to compensate for underinvestment in medical and social support over the last decade. Not everyone has the capacity or income to withdraw from places of work or the competence to deploy the digital devices which will now be critical for linking need with delivery. The more prosperous will suffer the cancellation of cruises and overseas holidays. The less so are in danger of becoming isolated in the full and most destructive meaning of the term.

Some may suffer like Donne. Others may enjoy the benefits of a change of pace, as Samuel Pepys did during another bout of plague-induced quarantine a few years after Donne. On the last day of December 1665, he reviewed the past year: “I have never lived so merrily (besides that I never got so much) as I have done this plague-time.”

David Vincent Professor of Social History, The Open University. His book A History of Solitude will be published by Polity on April 24

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION.