Filmmaker Martin Harvey documents the wildlife in Botswana, capturing the beauty of Okavango Delta and the Makgadikgadi Pans. The Okavango Delta is a delta in Northwest Botswana teeming with endangered species of large mammals, including cheetahs, white rhinoceros, black rhinoceros, African wild dogs and lions. UNESCO World Heritage protects two million hectares of this pristine delta. Okavango is an important site of support for elephants, as Botswana has the largest elephant population in the world. The delta is also species-rich in terms of plant life, possessing over 1,000 plant species. The Makgadikgadi Pans lie south-east of the Okavango Delta. From February to March, zebras, oryx, wildebeests, impalas and springbok graze Makgadikgadi National Park. The national park has never been inhabited by humans and is rather remote.

VIDEO: The Man Behind the World’s Largest Beach Cleanup

In 2015, Versova Beach in Mumbai was little more than a dumping ground for garbage and waste. After witnessing the devastating impact the refuse was having on the ocean, young lawyer Afroz Shah, with the help of 84-year-old neighbor Harbansh Mathur, decided to take matters into their own hands. What started off as a single man’s mission to clean up his favorite childhood beach turned into the world’s largest beach cleanup initiative with 70,000 adult volunteers and 60,000 student volunteers. After three years of work, Shah and hundreds of volunteers had cleaned up over 9 million kilograms of plastic and waste, with hopes to expand their initiative to other beaches in the future. The beach is now clean enough to welcome olive ridley sea turtles ready to lay their eggs to its shores. In 2016, Shah was awarded the UN’s Champions of the Earth award. He is currently working to clean Mithi River, Mumbai’s longest river.

Why Creating Rock Cairns is Dangerous and Wildly Illegal

Amplified by the social media trend of making and photographing these little towers, the prevalence of man-made rock cairns has reached an all-time high. But the illegal practice poses serious dangers to the surrounding environment.

A rock cairn. CanyonlandsNPS. CC PDM 1.0.

Trending on social media platforms like Instagram, “rock stacking” has become the latest nature fad. Seen as a challenge, those making their way through nature—whether it be at a park, a beach, a pond or elsewhere—have created a habit of creating these cairns or adding to pre-existing ones. People have even linked this habit to spirituality and luck, saying the higher the stack grows, the more luck a person has if they have added to the pile and that the practice grants them inner balance. But what might seem like a harmless human hobby is anything but that. With a plethora of environmental impacts, the ever-increasing number of rock cairns in our natural environment threatens the structure of multiple ecosystems, while also posing threats to the very humans who created them.

After the COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States, outdoor activities that accommodated for safe social distancing became a popular way to get out of the house. The Guardian reports that the National Parks Conservation Association noted a 20% increase in visitation at all national parks locations. With this uptake in visitation came the human impact on the land. Being uneducated in policies such as Leave No Trace (a principle that emphasizes the importance of humans to make as minimal an impact on nature as possible) and a severe lack of outdoor etiquette was instrumental in the rise in rock cairns.

Grand Canyon National Park visitors. Grand Canyon NPS. CC BY 2.0.

The environmental effects of rock cairns are the most threatening of the practice. Cairns made by water sources are among the worst, due to their impact on the surrounding food chain and ecosystems. Rocks disturbed by the side of a river, the edge of a pond, or even a lake, have devastating consequences on the animals that live there. Taking rocks from those areas, people dishevel the homes of macroinvertebrates, which are at the very basis of practically all freshwater food chains in the world. These little creatures provide a list of very important services, including keeping the water they inhabit clean by scavenging dead fish, plants and harmful bacteria, making them nutritious sources of food for animals in the area.

Without macroinvertebrates, our freshwater systems would not be able to self regulate, and the food chain—and ecosystems involved—would essentially crumble. By taking rocks from freshwater areas, people are stealing homes from these crucial creatures and inherently ruining entire ecosystems just to stack a few rocks. Additionally, other freshwater creatures feel the direct loss of habitat that the macroinvertebrates experience. Crayfish, algae, insect larvae and snails all lose homes to these cairns, all endangering these animals. Finally, the same threats that freshwater ecosystems face due to rock stacking can be seen in land environments. Reptiles, bugs and small mammals lose their natural habitats and plants are uprooted and disturbed.

Rock stack by a river. Angela7dreams. CC BY-NC 2.0.

In addition, rock cairns also pose threats to humans. Known to cause soil erosion, if rocks are being taken from the wrong places, large chunks of earth can become loose, leading to rock and mudslides. Further, large cairns, commonly found on mountain peaks and summits, have been known to fall over hillsides and hit hikers below.

The dangers of these cairns have made them illegal to make, unless done professionally by a park ranger. The penalties for making these cairns are equivalent to those for vandalism. Dubbed “rock graffiti,'' cairns are considered malicious mischief and warrant hefty fines that vary depending on location, and in some instances, rock stacking is punishable by jail time. Sometimes, when there is no other way to mark a trail path, rangers will make these cairns, having been trained to do so without disturbing the environment. However, those who make them for fun have been said to lead people the wrong way on hikes or walks. Because of the uptake in rescues, and all the other factors listed above, this practice of stacking rocks has been prohibited in national parks.

To Get Involved

If you ever come across a rock cairn, the National Parks Service (NPS) advises you to leave them be. The NPS asks that people do not disturb pre-existing cairns, do not add to them and especially refrain from building them. To read more about rock cairns from the NPS, click here.

Ava Mamary

Ava is an undergraduate student at the University of Illinois, double majoring in English and Communications. At school, she Web Writes about music for a student-run radio station. She is also an avid backpacker, which is where her passion for travel and the outdoors comes from. She is very passionate about social justice issues, specifically those involving women’s rights, and is excited to write content about social action across the globe.

Donating Used Clothing May Do More Harm Than Good

Donated clothes rarely end up in the hands of someone who needs them. Instead, they usually end up in landfills or overwhelming already struggling industries.

Landfill in Kenya. Thad K. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Many Americans assume donating is the best thing they could do with their old, unwanted clothing. However, in reality, more than 80% of donated clothing ends up in landfills. Only clothing in the best condition is accepted into secondhand stores in the U.S., such as Goodwill or Buffalo Exchange. Even then, if the clothing remains in the store without being purchased for weeks at a time, the store itself often disposes of it. The rejected clothing often ends up in landfills or is shipped overseas.

Americans buy five times as much clothing, on average, than they did 30 years ago. However, the quality of the clothing most people buy has decreased due to fast fashion trend cycles, resulting in an average of only seven wears per piece. The increase in purchasing combined with the decrease in wear time has resulted in an overwhelming influx of clothing donations in the past 30 years.

In theory, shipping unwanted clothing to countries seems like a good thing; it has the potential to create jobs and provide more affordable clothing. Unfortunately, many countries (mostly in East Africa, where unwanted clothes are most commonly sent to, with the exception of Ghana) cannot handle the sheer mass of the clothing they are receiving. The U.S. ships up to 700,000 tons of clothing overseas every year, which is simply too much for the textile and clothing industries to disperse. Additionally, secondhand clothing sells for such a small fraction compared to new clothing in East Africa, causing local companies unable to compete with cheap clothing to go out of business.

Clothing Donation Stop. Laura0509. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Several East African countries (Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Burundi and Rwanda) even signed a ban on the importation of used clothing from the U.S. in 2016. The Trump administration negotiated with the East African Community (EAC) to reverse the ban, which they did, mostly due to international pressure. With that being said, certain countries, such as Kenya, claim to rely on the influx of clothing from the U.S. to keep their textile industry up and running. But while that is the case for Kenya, donated clothing does more harm than good for the majority of East African countries.

In terms of the environment, secondhand clothing markets in every country in the world are simply unable to keep up with the amount of discarded clothing as the fast fashion industry continues to ramp up production exponentially. Whether the clothing begins its journey in a thrift store in the U.S. or on a plane to Kenya, it is ultimately most likely to end up creating more waste. The myth of clothing donation is part of what propels the fast fashion industry; people think donating their clothes will have an ultimately positive impact, and so they feel justified in continuing to amass more clothing.

Ultimately, the most effective fix for this problem would be to reduce collective clothing consumption. The less unnecessary clothing that is bought, the less clothing waste will be produced. With that being said, there are other options to reduce your clothing waste. Instead of donating your unwanted clothing, giving it directly to someone that you know wants and will use it ensures that it won’t end up in a landfill, at least in the short-term. Donating your clothing to homeless or women’s shelters is also another option, as they have more need than thrift stores such as Goodwill or Salvation Army. However, even when it comes to donating clothing to shelters, the clothing must be in good enough condition to actually be worn. If it’s not, another option is to keep and repurpose it yourself. Old fabric can be used as stuffing or kept for a future art project. All in all, donating excess clothing can be the last resort, which comes after making an effort to buy less, trade within your own circles and repurpose used materials.

Calliana Leff

Calliana is currently an undergraduate student at Boston University majoring in English and minoring in psychology. She is passionate about sustainability and traveling in an ethical and respectful way. She hopes to continue her writing career and see more of the world after she graduates.

Sand Mining Threatens Coastline as Sierra Leone Rebuilds

Within a few miles of Sierra Leone’s capital, sand mining is having a devastating effect. As beaches slowly disappear, so do the country’s hopes of post-war revival.

Freetown Beach in Sierra Leone, Erik Cleves Kristensen, CC BY 2.0

Twenty years after Sierra Leone's 11-year civil war, the economic promises of sand mining prove to be costly. The war, which took thousands of lives and led nearly half the country's population into poverty, destroyed most of the country. What followed was a construction boom made possible by an essential ingredient of modern civilization: sand. However, as Sierra Leone’s 300 miles of glorious beaches slowly disappear, so does the revival of tourism and the protection of 55% of the population who live along the country’s coast from the dangers of rising sea levels due to climate change.

As part of a post-civil war move to help communities benefit from local resources, Sierra Leone’s central government gave regulation of sand mining to local councils. Under the 2004 Local Government Act, local committees operate the trucks and strictly hire local people to mine the sand. After a long day of mining, the sand is dried and sold to developers to pave and extend roads as new homes, hotels and restaurants go up across the country.

Government officials defend sand mining as an essential source of jobs and a necessary component in rebuilding Sierra Leone. Kasho Cole, chairman of the Western Area Rural District Council, told the Los Angeles Times that his council is “sensitive to environmental concerns, having banned sand mining on certain beaches because of the devastation it has already caused.”

Cole also acknowledged that assessments had not been carried out anywhere in the district to determine sand mining’s environmental impact. Due to large-scale illegal sand mining operations, Cole could not provide a definite amount of sand extracted from the beaches.

Sand theft, the unauthorized and illegal form of sand mining, has led to a worldwide non-renewable resource depletion issue, causing the permanent loss of sand and significant habitat destruction. Sand mining has already made a significant environmental impact in North Stradbroke Island and Kurnell in Australia; the Indian states of Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Goa; and the Red River in Yunnan, China.

In the United States, the sand mining market generates slightly over $1 billion per year. The industry continues to grow annually by nearly 10% because of its use in hydrocarbon extraction. Globally, sand mining is a $70 billion industry, with sand selling for up to $90 per cubic yard.

In Sierra Leone, sand mining operations are regulated on John Obey Beach, a village 20 miles south of the Western Area (Freetown Peninsula.) According to the Environmental Protection Agency, sand mining should be banned on all beaches apart from John Obey. However, when the police leave the beaches at 5 p.m., the mining continues after dark.

Efforts to address the issue are hampered by conflicts of interest from those involved: miners who need the work, construction companies who need the supply and investors who are getting rich taxing the sand. Last year, a press statement from the local police force confirmed “certain service personnel appear to be aiding and abetting this illegal act.”

As dump trucks continue to haul sand away and tides push further inland, John Obey Beach is slowly disappearing—taking trees, businesses, homes and dry land with it as far down the coast as Bureh, a surf town two miles south. While the activity contributes to Sierra Leone's coastal erosion, which is proceeding at up to 6 meters a year, the removal of sand also changes wave patterns that move sand along the coast, altering the quality of surf that Bureh, a renowned surf spot in Africa, is known for.

Prior to the war, Sierra Leone’s beaches were packed with adventurous travelers from around the world. Kolleh Bangura, the director of Sierra Leone’s Environmental Protection Agency, told The New Humanitarian that “sand-mining is a calamity for the tourism industry… Anywhere in the world, sand is the resource of tourism, but now our beaches are being degraded.”

Lakka, a coastal town located 10 miles from Freetown, was once known for its large beaches and seaside resorts, offering a glimpse of the future if actions are not taken. Sand mining on Lakka Beach is illegal now, but the ban came too late—leaving a thin wedge of sand lined by crumbling buildings, many of which have been left abandoned.

Even the miners themselves recognize sand mining is not sustainable; however, with a youth unemployment rate of 70%, the pressure falls on the government to provide alternative jobs. “In time, they need to ban it, as we want to bring tourism here,” Abu Bakarr, a sand miner, told The New Humanitarian. “But we need sand-mining to sustain our lives…The government needs to give us jobs. If there are no jobs, the youths will mine the sand.”

Papanie Bai-Sessay, the biodiversity officer at Conservation Society of Sierra Leone, told the Los Angeles Times that “the sand has been a buffer… we are destroying our first line of defense. If we don’t stop, it will be a disaster for millions.”

Claire Redden is a freelance journalist from Chicago, where she received her Bachelor’s of Communications from the University of Illinois. While living and studying in Paris, Claire wrote for the magazine, Toute La Culture. As a freelancer she contributes to travel guides for the up and coming brand, Thalby. She plans to take her skills to London, where she’ll pursue her Master’s of Arts and Lifestyle Journalism at the University of Arts, London College of Communication.

5 Everyday Products that Hurt the Environment And Their Sustainable Alternatives

In our fast-paced lives, it can be difficult to remember to make sustainable choices. Here are a few products most of us use every day that have a negative effect on the environment.

Image Credit: HuffPost UK

Plastic Bags

You’ve probably heard this one before, but despite widespread coverage of the issue, between 500 billion and 1 trillion plastic bags are used worldwide every year. These bags take enormous amounts of energy to produce and ship; they are difficult to recycle, do not decompose and emit toxic chemicals into the environment.

Fortunately, there are many green alternatives to the plastic bag. Fabric or canvas shopping bags are relatively inexpensive to purchase and can be reused for grocery shopping.

Produce Bags

Produce bags often get left out of the conversation surrounding plastic bags, but they are made from the same materials and are equally harmful. Try using washable mesh produce bags instead—they are fairly cheap and can be reused.

Exfoliant Products

Many facial soaps contain tiny plastic microbeads that help exfoliate the skin. These beads are too small to be filtered during sewage treatment and have started to build up in lakes and oceans. In one year alone, researchers found 1,500 to 1.7 million bits of plastic per square mile in the great lakes. California, Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, Maine, Maryland and New Jersey have already banned microbeads, and it is likely that other states will follow. There are many alternatives to these soaps that are environmentally friendly and better for the skin. Try using oatmeal, raw honey or coffee ground scrubs—often you can make them yourself from ingredients you probably already have in your pantry.

Coffee Pods

They may be convenient, but single-serve coffee pods aren’t recyclable, meaning almost all of the 10 billion made each year end up in landfills. Brewing coffee the old fashioned way may take a few minutes longer, but it will reduce your waste in the long run. You can recycle unbleached paper filters and compost the grinds or use them in a face scrub.

Non shade-grown coffee

While we’re on the subject, the coffee industry is responsible for massive amounts of deforestation and water pollution. Buying shade-grown coffee is easier on the environment because it allows trees to grow alongside the coffee plants, which not only guards against deforestation, but controls soil erosion and filters carbon dioxide. Shade-grown beans also mature at a slower rate, which creates a delicious flavor.

Prepackaged Food

From juice boxes to chips, almost nothing you buy at a grocery store is free of plastic packaging. While these products are convenient, they pose a risk to the environment. Like plastic bottles and bags, plastic food packaging is difficult to recycle and does not decompose. While there are alternatives to prepackaged food, such as zero waste grocery stores, they can be hard to come by. Try to reduce the amount of packaged food you buy, but when necessary, buy bulk products instead, as single-serve items have more packaging.

In the end, working to reduce or eliminate your consumption of these five products is a step towards a greener planet and more sustainable lifestyle.

EMMA BRUCE

Emma is an undergraduate student studying English and marketing at Emerson College in Boston. She has worked as a volunteer in Guatemala City and is passionate about travel and social justice. She plans to continue traveling wherever life may take her.

Saving More Elephants with Honey than with Vinegar

The vast majority of people around the world have only seen African elephants from a television screen, from behind fences in zoos, or- if they’re lucky- from a safe seat in a safari car as it bounces past the grazing giants of the Serengeti. From those vantage points, it’s impossible to look at the massive bodies, dexterous trunks, and intelligent eyes of the elephant and not feel a keen sense of wonder and awe. Elephants are some of those ‘charismatic megafauna’ that capture the hearts of people worldwide, making conservation efforts seem like a no-brainer. Who wouldn’t want to protect and save these wise, complicated, prehistoric-seeming creatures?

The people who share a homeland with elephants might be in that category.

Elephants are herbivores, and must eat almost constantly to maintain enough calories to support their gargantuan bodies- individual adults can consume between 200 and 600 pounds of food per day. Traveling in family groups that can consist of 10-20 elephants or more, that’s an incredible amount of vegetation needed to sustain a herd.

In addition to the grasses, roots, fruit, and bark found in the wild, elephants have quickly learned that their human neighbors can provide a tasty supplement to their diet- fields of carefully tended yams, cassava, corn, plantains, and grains. A herd of elephants can destroy a subsistence farmer’s means of food and income for the whole year in just a single night.

These episodes of crop raiding have created dangerous situations for people living in sub-Saharan Africa. Desperate to protect their livelihood, farmers may try to stay awake all night, ready to yell and bang pots in an effort to frighten away any pachyderm pilferers. However, elephants are not so easily startled by humans, and have been known to attack and kill would-be crop defenders. In anger and frustration, a group of villagers may then retaliate and try to kill the next group of elephants they see. These was creating a vicious cycle of animosity on both sides; elephants are intelligent creatures, and once they began associating humans with pain and disruption, there was evidence that they became more violent to humans in future encounters.

The heightened tensions were disastrous for both humans and elephants, and a solution was desperately needed to protect both vulnerable groups.

There had been local rumors buzzing around for a while that claimed elephants were afraid of bees, but it wasn’t until researchers Fritz Vollrath, Dr. Iain Douglas-Hamilton, and Dr. Lucy King investigated that those results were confirmed to the rest of the world. When confronted with the sound of bees buzzing, the elephants would immediately retreat and send out a rumbling call that would warn other elephants of danger in the area. Additionally, the elephants would begin shaking their heads and dusting themselves, suggesting that their skin was sensitive to bee stings and that they knew to associate the sound with potential pain.

Armed with this knowledge, researchers, nonprofits, and government groups set out to make affordable beehive fences that could protect precious crops from marauding elephants and protect elephants from learning dangerous behaviors that would bring them into conflicts with humans.

In the last few years, as the success of the beehive fences has been proven time and again, they are gaining in popularity throughout Africa. The fences are genius in their simplicity; a hanging box hive is hung from a fence every ten meters, all connected by wire. This way, if an elephant brushes against the fence or wire, the hives will swing and rock and the bees will swarm out to get away from the disturbance. Nearly 100% of the time, the elephant will turn tail and run, warning its family members to stay away. Thanks to their famous memories, the elephants won’t soon forget that lesson.

Not only do the fences allow farmers to harvest their full crop without any losses to elephants, but the honey produced in the hives has also found a niche market. “Elephant-Friendly Honey,” as it’s called, has been a huge hit with globally conscious consumers who increasingly want to know that the products they are buying support a good cause.

African elephant populations have slowly been increasing since the poaching crisis that decimated their numbers in the 1970’s and 1980’s. While the rest of the world celebrated that fact, many African people living in close proximity to elephants couldn’t see why people around the world were so eager to save the creatures that were plaguing their lives and livelihoods. Now, thanks to an increased effort to help protect people along with ivory-tipped neighbors, more and more people are able to view their globally treasured wildlife with a sense of pride instead of fear.

Katharine Rose Feildling

Katharine Rose was born in Maryland and is currently working for the Condor Recovery Project in California. She studied wildlife management in East Africa, and gained a deep passion for wildlife conservation, social activism, and travel while there. Since then, she has traveled and worked throughout the United States, South America, and Asia, and hopes to continue learning about global conservation and inspiring others to do the same.

The World’s Electronic Waste is Ending Up in Ghana’s Landfill

While new tech gadgets launch every few months, the buildup of electronic waste is being sent to Ghana and damaging the citizens’ health.

Location, Ghana. Fairphone. CC BY-NC 2.0

The capital city of Accra in Ghana is home to the largest e-waste landfill, Agbogbloshie. Electronic waste or e-waste is waste material with any battery or power cable. It ranges from everyday appliances to laptops, circuit boards, lamps, phones, etc. If these items are not disposed of properly, they can become harmful to the environment and people. An estimated 250,000 tons of electronics are sent every year to the dumpsite. The site not only houses e-waste, but about 40,000 Ghanaians inhabit the area alongside livestock.

The e-waste arrives in Ghana through the Port of Tema, about 20 miles east of Agbogloshie. Most of the items in the container ships are from the United States or Western Europe. The electronics are secondhand and sent to Ghana with the idea of being refurbished then sold. The majority of the items cannot be fixed and become e-waste, which is then taken to Agbogbloshie. Once the electronics arrive at the dumpsite, there is an entire process the electronics go through. First, small collectors sell the items to scrap dealers known as “masters.” The scrap dealers then have their workers, known as “boys,” use their bare hands, hammers and other tools to break apart the valuable metals inside. At times insulated wires are bundled together and taken to the “burner boys” they’re in charge of burning the plastic off of the wires. In doing so, they’re able to retrieve valuable metals. The metals include copper, aluminum, zinc, silver and others. Once the metals are recovered, they are weighed and sold for instant cash.

PCBs Used to Extract Metals. Fairphone. CC BY-NC 2.0

The supply and demand is what fuels the toxic pollution in Agbogbloshie. As soon as the bulk of metals and wires are sold, they are exported out of Ghana and reused to produce new devices. The men and young boys who do this harmful labor are usually from rural northern cities searching for work to provide for their families back home. A “burner boy” will make about $40-50 Ghanaian cedis a day (US$6-8). Living in extreme poverty and barely making enough to move further up the chain, along with paying the ultimate price with their lives. They work arduously with no protective gear and no government regulations. At times, these young men and children have multiple health issues due to the toxic fumes and chemicals that leak from the electric waste. They face chronic nausea, debilitating headaches, skin diseases, burns, respiratory problems, infected wounds and cancer among others. All these issues are brought on by the toxic work environment, pollution and lack of regulations. Most people know that this line of work is debilitating to their health. However, the desperation for survival is the driving force.

The people who work and live in Agbogbloshie are not the only ones suffering; the livestock is, too. The toxins are entering the food chain as cattle roam and graze the dumpsite freely. This is concerning as the Agbogbloshie area is home to one of the largest food markets in Accra. Most of the cows and chickens are slaughtered and eaten by the residents, which then ingest the high-level toxins. In addition, the water is also being contaminated as Agbogbloshie is situated on the Korle Lagoon. This lagoon is filled with piled-up waste of all sorts and links to the Gulf of Guinea, the Northeastern part of the Atlantic Ocean.

Goat Freely Roaming. Fairphone. CC BY-NC 2.0

Agbogbloshie is known to many of the locals as Sodom and Gomorrah. These biblical cities are synonymous with Agbogbloshie’s difficult living conditions. Although harsh, the people of this slum depend heavily on electrical waste in order to make a living. The Ghanian government has condemned the activity that’s taking place here. However, it has not lessened. As of now, change might be taking place in the near future. The German agency, GIZ, is in the middle of delivering a $5.5 million project for the people of Agbogbloshie. The plan is to build a sustainable recycling system and a health clinic and football pitch for workers. Much more will need to be done to keep the people’s health intact and away from this harmful environment. However, this is a start in bettering the status quo.

Jennifer Sung

Jennifer is a Communications Studies graduate based in Los Angeles. She grew up traveling with her dad and that is where her love for travel stems from. You can find her serving the community at her church, Fearless LA or planning her next trip overseas. She hopes to be involved in international humanitarian work one day.

8 Animals Recently Declared Extinct

Anywhere from 24 to 150 animal species go extinct daily, with human activity as a primary cause. Here are eight animals that have recently gone extinct.

Many animal species have recently gone extinct at the hands of humans, which should be a wake up call about how our actions can harm wildlife and the environment. Learn about these eight recently extinct animals to see what you can do to help.

Poison Arrow Frog (Dendrobatidae). Jerry Kirkhart. CC BY 2.0.

1) Splendid Poison Frog

The IUCN added the splendid poison frog to the Red List of Endangered Species in 2004 and officially declared the species extinct in 2020, making it one of the most recently extinct species on the planet. These frogs are often referred to as poison arrow or poison dart frogs, and they are the brightest colored frogs in the world. Splendid poison frogs’ diets cause them to secrete toxins from their skin, and their bright colors warn predators of their toxicity. While the species lived in the humid lowlands and forests of western Panama, deforestation and habitat degradation severely harmed these areas and threatened the frogs. Human invasion such as with logging and construction in the area decreased the species’ population significantly.

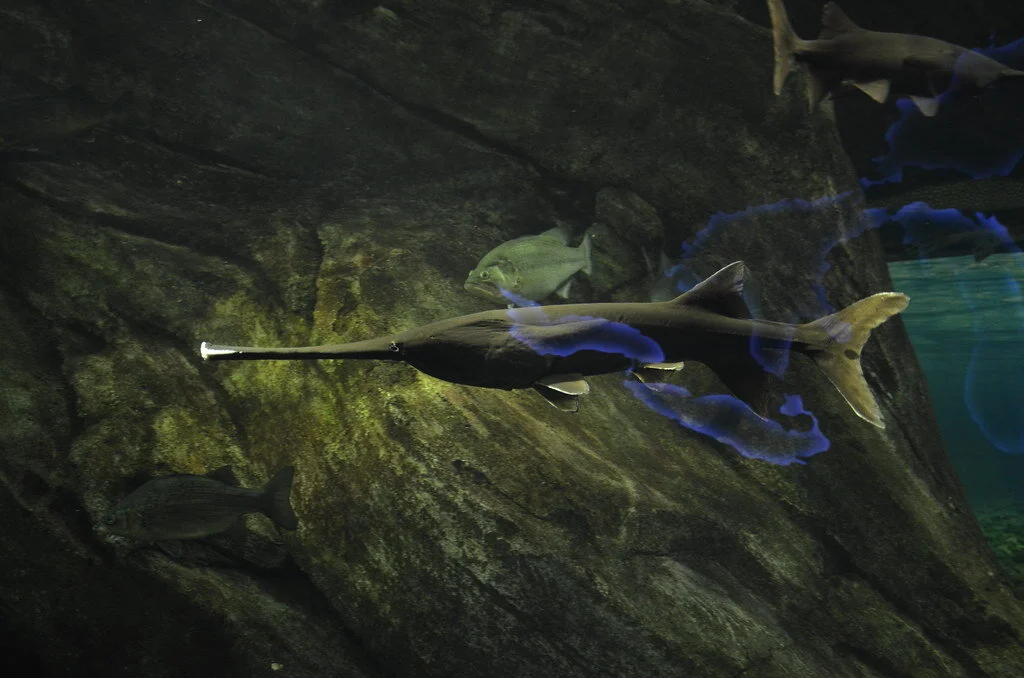

2) Chinese paddlefish

Like the baiji dolphin, the Chinese paddlefish (also known as the Chinese swordfish) was most commonly found in the Yangtze River and was one of the largest freshwater fish in the world. This ancient fish species has lived since the Lower Jurassic period and survived the mass extinction that killed off the dinosaurs and many reptiles. Yet, the biggest threat to their existence was human activities. In the 1970s and 80s, overfishing and construction severely decreased the species’ population size. By 1993, this disruption caused the fish to become functionally extinct, which meant that the species lacked the numbers to meaningfully reproduce. The species has not been spotted since 2003, and it was officially declared extinct in 2020.

Sumatran rhino. David Ellis. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

3) Sumatran Rhino

Sumatran rhinos—also known as Asian Two-Horned Rhinos—are the smallest and most endangered rhino species in the world. They generally live for between 35 and 40 years, and their habitat is the dense tropical forests mainly on the Indonesian island of Sumatra. Due to poaching, the species’ numbers have decreased more than 70% over the last 20 years. The Sumatran rhino was officially declared extinct in mainland Malaysia in 2015 and in Malaysian Borneo in 2019. The last Sumatran rhino died in 2019.

4) Pinta giant tortoise

In 2012, “Lonesome George,” the world-famous tortoise, passed away at the estimated age of 100 years. George was the last remaining land tortoise from Pinta Island, a northern island in the Galapagos, and lived at the Charles Darwin Research Station since he was found in 1971. Most of his species went extinct because they were used as an onboard food source for 19th-century whalers, as well as due to habitat destruction. The Galapagos National Park searched for a mate for George for over three decades to try to save the Pinta subspecies, but they could not find one. When George passed away in 2012, the Pinta subspecies passed with him.

Black rhino. Corrie Barklimore. CC BY 2.0.

5) Western black rhino

The western black rhino, which was the most uncommon of the black rhino subspecies, went extinct in 2011. In the past, the species had a large range across central and western Africa, but it was not able to survive in the 20th century. Hunting for sport quickly decreased rhino populations, and industrial agriculture cleared rhino habitats to make fields and settlements. In addition, between 1960 and 1995, 98% of black rhinos were killed by poachers. By 1980, the western black rhino’s range had shrunk to only two countries: Cameroon and Chad. The species’ population had fallen to about 10 rhinos by 1997. Due to this, the International Union for Conservation of Nature added the species to the critically endangered species list in 2008, and declared them extinct in 2011.

Baiji, Lipotes vexillifer. CC BY-SA 4.0

6) Baiji

Commonly referred to as the Yangtze River dolphin, Baiji is the first dolphin species to become extinct because of human activity. The Yangtze River was the Baiji’s home for 20 million years, and it only took humans 50 years to completely wipe them out. The Baiji’s ability to communicate, navigate, avoid danger and find food became very challenging as the river became noisier and noisier due to humans. In 2006, researchers embarked on a six-week journey on the river for over 2,000 miles to search for the Baiji, but they were not able to detect any existing dolphins. They were declared extinct in 2007.

Treehunter. Nick Athanas. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

7) Cryptic treehunter

There have been no records of the cryptic treehunter since 2007, mainly due to extensive habitat loss in its region, Brazil. Cryptic treehunters were usually found in grasslands, woodlands and humid forests. Logging and conversion of forest to sugarcane plantations and pastureland was a major reason for the species’ decline. Some scientists believe that the species has not completely vanished due to their incredible hiding abilities, but since one has not been seen since 2007, it is unlikely.

Bouquetin—the French name for Pyrenean ibex. Jean-Raphaël Guillaumin. CC BY-SA 2.0.

8) Pyrenean ibex

Once a large population which roamed across France and Spain, the Pyrenean ibex is one of two subspecies of the Spanish ibex that was declared extinct in 2000. The last Pyrenean ibex died in January of 2000 when a falling tree killed her. After she died, scientists took skin cells from her ear and preserved them in liquid nitrogen. In 2003, her DNA was cloned into a new ibex, becoming the first species to be “unextinct.” However, the clone died minutes after it was created due to lung issues. Scientists suspect that the species went extinct due to poaching, disease and competition for food.

Isabelle Durso

Isabelle is an undergraduate student at Boston University currently on campus in Boston. She is double majoring in Journalism and Film & Television, and she is interested in being a travel writer and writing human-interest stories around the world. Isabelle loves to explore and experience new cultures, and she hopes to share other people's stories through her writing. In the future, she intends to keep writing journalistic articles as well as creative screenplays.

Study Predicts African Great Apes Will Lose 94% of Their Territory

A new study about the effects of climate change, land use and human population growth on African great apes found that they may lose up to 94% of their habitat by 2050.

A mountain gorilla in Uganda. Rod Waddington. CC BY-SA 2.0

Great apes are humanity’s closest relatives. They are also a highly endangered group of animals, and experts believe that this status will likely worsen in the coming years. A new study published in the journal Diversity and Distributions predicts that the combined pressures of climate change, human land use and human population growth will lead to immense territory losses for African great apes in the next 30 years.

There are four types of great apes: gorillas, bonobos, orangutans, and chimpanzees. Africa is home to a number of species of great apes, including Cross River and Eastern and Western gorillas, as well as bonobos and chimpanzees. The situation for these species is already critical. All are listed as either endangered or critically endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Red List of Threatened Species, a comprehensive list detailing the conservation status of animals around the world. And, as wild areas are destroyed for timber, minerals and food; the human population expands; and climate change alters the land where great apes can comfortably live, experts warn that African great apes could lose a devastating portion of their range by 2050.

The study was conducted by nearly 60 scientists from different research institutions, universities and conservation organizations. The scientists used data about African great ape populations from the IUCN database and then modelled the future effects of climate change, land use and human population growth. Using this data, the scientists analysed a best case scenario, where action is taken to protect the environment , and a worst case scenario where nothing is done. There is little difference in the two outcomes. Both result in massive range loss for African great apes, with 85% range loss by 2050 in the “best case” scenario and 94% by 2050 in the “worst case”.

Half of this lost range will be territory inside national parks and other protected areas, the study predicts. Although these areas are safe from human land use, they will still be affected by climate change, which will make the habitat unsuitable for great apes. Most great ape species prefer to live in lowland habitats, but climate change will make them hotter and drier. In areas where there is no higher lands, apes will be left with nowhere to live. In areas where there are uplands, however, experts suggest that great apes will attempt to migrate upward, following the climate and vegetation they prefer.

Yet, even apes that have the ability to migrate as their range decreases may not have enough time to do so. Apes reproduce slowly, have a low population density and require a very specific diet. All of these factors mean that apes are generally not efficient migrators compared to other species; to fully acclimate to a new habitat would take great ape species longer than the 30 years the study predicts they have left.

The authors of the study urge that their findings be used to guide conservation efforts for African great apes in order to prevent irreversible population losses. Their findings suggest that the range loss can be mitigated through specific conservation efforts that focus on new and existing protected areas, as well as connecting habitats that are predicted to still be suitable for great apes in the future.

Rachel Lynch

Rachel is a student at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY currently taking a semester off. She plans to study Writing and Child Development. Rachel loves to travel and is inspired by the places she’s been and everywhere she wants to go. She hopes to educate people on social justice issues and the history and culture of travel destinations through her writing.

Hidden Afghanistan

From the apricot and walnut groves of the beautiful Panjshir valley, to the strips of cultivated green set against the dry pink and tan of the mountains in Bamyan, to the glittering sapphire blue lakes of Band-e Amir, I went in search of the real Afghanistan.

The country’s rich cultural history, rugged landscape, and the legendary generosity of Afghan people, have long been a draw for adventurers and travellers alike, but for now, still struggling with deep-rooted insurgency, Afghanistan remains firmly off the radar for most. Plagued by terrorism and war, the most recent cycle of bloodshed and instability has left the country with a reputation for violence and little good ever makes our TV screens in the West. For too many, our narrative around countries like Afghanistan has been reduced to a single story.

As part of my work on a book called Life in the Himalayas — looking at people’s everyday working lives throughout this diverse and magnificent mountain range, from the high plateau of Tibet to the foothills of Myanmar — I spent three weeks documenting the lives of agropastoralists in Afghanistan, and exploring this battered but beautiful country. I set out to focus on rural areas, everyday life and culture, going in search of the real Afghanistan, away from the vestiges of war and terror.

Kabul

I started off in the bustling markets in the country’s capital, Kabul, a chaotic little jungle of trinket shops, carpet sellers and giant chunks of Lapis filling windows. Occasionally I felt uneasy under the stares of watchful eyes as I poked my way through the dusty streets. Mostly it felt like any other vibrant bazaar in Asia, people going about their busy day.

I ate in smoke filled restaurants sitting cross-legged on cushions. Whole sheep carcasses are hung directly above the stove and the cook simply butchers off the bits he needs and throws them into a big black pot, along with fistfuls of fresh herbs and spices. Huge roundels of hot naan breads are piled high on the tables and you pay for what you eat. There is a genuine old-world feeling in Kabul that is rare to find these days.

Panjshir Valley

From Kabul I travelled to Istalif, a district famous for its distinctive blue pottery, and then by road to the stunning Panjshir Valley, one of the most celebrated places in Afghanistan, located in the heart of the Hindu Kush mountains. Its name means ‘Valley of the Five Lions,’ which according to local legend refers to five spiritual protectors or ‘wali’ who built a dam here during the early 11th century AD for Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni.

The Panjshir river starts from a narrow gorge where snowmelt turn the river into a torrent, rich with fish. It gradually widens into the valley to reveal carefully irrigated fields of wheat and maize dotted with walnut, apricot and mulberry groves. 90 percent of farmers in Panjshir Province practice subsistence agriculture, and the war has destroyed irrigation canals and orchards, making many aspects of farmers’ lives a challenge.

In recent years, however, international initiatives have assisted local and regional government leaders to introduce improved varieties of wheat and educate farmers on methods for improving yields and irrigation.

Bamiyan

In the heart of the Hazarajat, Bamiyan is surely one of the most beautiful parts of the whole country. It was a popular tourist destination during the 1970s, but a decade later became a symbol of resistance to the Soviets. Today, although the valley is still dominated by the gaping cavities in the cliff face, and the rubble is a constant reminder of the Taliban’s rage and destruction of the two ancient Buddha, there is far more to Bamiyan.

Guarding the entrance to Bamiyan valley, the ruins of Shahr-e Zohak form a dramatic citadel — perched high on the cliffs at the confluence of the Bamiyan and Kalu rivers. The towers here are some of the most imposing in all of Afghanistan, and are made of mud-brick on stone foundations, with intricate geometric patterns built into their walls. With no doors, they were accessed by ladders that the defenders pulled up behind them.

Looking down from the citadel, the views are incredible, with the thin strips of cultivated green in neighbouring valleys like Fulladi providing a striking contrast to the dry pink and tan of the Koh-i Baba mountains.

At first glance, the barren hills of the Bamiyan valley appear to promise little, but the snowmelt that issues from them each spring allows the farmers here to irrigate the valley floor and grow crops like potatoes.

Donkeys are still the main source of transport in this rural province, and shepherds and their flocks are often compelled to walk long distances.

Band-e Amir

Meanwhile, the glittering sapphire blue lakes of Band-e Amir are one of Afghanistan’s most astounding natural sights. In April 2009, Band-e Amir was named the country’s first national park, 36 years after a previous attempt to do so was interrupted by decades of political strife and war.

Formed by the mineral-rich water that seeps out of faults and cracks in the rocky landscape, the six linked lakes of Band-e Amir sparkle like jewels against the dusty mountains that surround them.

Over time layers of hardened mineral deposits called travertine have built up on the shores, to create the dramatic sheer sides that now hold the lakes in place. Local lore tells a different story, asserting that these natural dams were thrown into place by Hazrat Ali, the prophet Muhammad’s son-in-law, during the reign of the infidel king Barbar.

Before gaining its status as a national park this region experienced significant habitat destruction for firewood and farmland, overgrazing and overhunting — the snow leopard has now vanished here — and also damaging fishing practices that involved using hand grenades. Today Band-e-Amir is protected by a small group of park rangers, and is still home to ibex (wild goats), urials (wild sheep), and wolves. Although numbers of visitors to the park remain small, it is hoped that in time, this region will become an important area for tourism in Afghanistan.

Herat

Finally in Herat, the country’s old cultural heart, I felt more welcome than anywhere else in the country. Chatting to passing nomads on the outskirts of the city, inside its little bazaars, visiting the Friday Mosque — one of Islam’s great buildings — I spoke openly with burqa sellers about the state of the country. Here I discovered an Afghanistan most people simply don’t know exists. Afghans are proud of their culture, they are welcoming, generous and have a sharp sense of humour.

On my last day, insurgents attacked one of the big hotels in Kabul. I could hear helicopters and sirens all day and was advised that it was best not to leave the house. The next morning a gunfight broke out beside the road on the way to the airport. Sand bags and gun turrets occupy every corner and the frequent security checks are a sobering reminder of how unstable and precarious daily life is for the people of Afghanistan, whose resilience remains under great strain in these troubled times.

Let us hope that one day, a lasting peace will come to this battered, but proud and ancient country, allowing travellers to experience its beauty and welcome, and to step onto the fabled silk route once more.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON MAPTIA.

Driven by his passion for travel, the environment and remote cultures, Alex Treadway has travelled to dozens of countries around the world on assignment.

Lake Moogerah in Queensland, Australia. Lenny K Photography. CC BY 2.0.

Australia’s National Parks are Natural Wonders of the World

Australia has long been an escape for those who are seeking to get in touch with nature. While the country is most famous for its semiarid and desert regions, Australia is one of the few countries in the world which can boast a majority of the Earth’s 14 ecoregions—the continent is home to eight.

While Australia is the sixth-largest country in the world, it is one of the most sparsely populated. According to the 2016 census, 23.4 million people call Australia home, with 80% living less than 60 miles from the coast, yielding a population density of 9 people per square mile. This has left the vast majority of Australia’s ecoregions untouched by human development.

Australia’s eight ecoregions range from the very wet tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests—found exclusively on the northeast coast of Queensland—to the deserts and xeric shrublands which comprise a majority of the country’s landmass.

This vast diversity in natural habitats makes Australia one of the most biodiverse places in the world. According to the 2009 Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World report, 147,579 described species had been confirmed, with the estimate for the total number of species which call the continent home at 566,398. A majority of these species are endemic to Australia, ranging from platypi to emus to kangaroos to koalas.

The National Reserve System, Australia’s counterpart to the United States’ National Park Service, is a largely new system of protected areas with the goal of preserving Australia’s vast biodiversity and ecoregions. While the first national park in the country, the Royal National Park in New South Wales, was established in 1879, the National Reserve System did not come into existence until 1992 with the ratification of the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Since then, the National Reserve System has gone on to become a vast network of over 13,000 commonwealth, state and territory protected areas, with a combined landmass of 370 million acres—about 19.75% of the country’s total landmass. Ranging from the expansive Kosciuszko National Park in New South Wales, which includes high summits which regularly see snowfall, to the famous Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park in the Simpson Desert, Australia’s National Reserve System truly offers something for everyone.

The Devil’s Marbles, a natural rock formation in the Northern Territory. Mark Wassell. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

For travelers who are looking to explore the desert and see some unique rock formations, Western Australia’s Nambung National Park cannot be beaten. Located in the Pinnacles Desert, Nambung offers picturesque desert views, beautiful beaches at Kangaroo Point and Hangover Bay, and the aforementioned rock formations called stromatolites. The park can be enjoyed year-round, but the most popular time to visit is in September and October, when its wildflowers are in full bloom.

Located on the southwestern coast of Victoria, Port Campbell National Park is home to breathtaking cliffs which overlook the Southern Ocean and a variety of natural islets, gorges and arches. One of the most famous, the London Bridge, provides the perfect spot to view a population of little penguins come ashore, as well as whale watching in the winter months. Port Campbell can be enjoyed year-round, with different flora and fauna prevalent throughout the various seasons of the year.

For those who can’t get enough of the rainforest, Daintree National Park in Queensland is a popular park for camping and hiking. A part of the Wet Tropics of Queensland, which were designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1988, the park is home to a variety of unique species, including 430 birds, 23 reptiles and 13 amphibians. While the park is open year-round, the best time to visit is during the drier, cooler months from May to September.

Jacob Sutherland

Jacob is a recent graduate from the University of California San Diego where he majored in Political Science and minored in Spanish Language Studies. He previously served as the News Editor for The UCSD Guardian, and hopes to shed light on social justice issues in his work.

COVID-19 Slows Africa’s Progress Against Poaching

Poaching is a last resort for villagers who lost their jobs due to COVID-19 lockdowns. Conservationists now struggle to preserve endangered species.

A valuable commodity. valentinastorti. CC BY-NC 2.0.

They march through the field with chainsaws, the rhinos sedated. What follows is no gruesome act of poaching. It’s the exact opposite. Workers at the Spioenkop Nature Reserve in South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal province rev their chainsaws and go to work sawing off the rhino horns. “It has a face mask put on it to cover its vision, it has earplugs put into its ears [...] so that reduces trauma to the animal,” says Mark Gerrard of Wildlife ACT, a nonprofit that protects African wildlife. “We’ve got to remind ourselves that this [a rhino’s horn] is just keratin—this is really just fingernails.”

These rhinos’ horns will grow back in 18 to 24 months, but in the meantime, poachers won’t hunt them for the priceless commodity. Armed with only chainsaws and sedatives, the conservationists at the reserve are combating Africa’s interminable poaching problem. If a rhino has no horns, poachers have no reason to kill it. This fact doesn’t make the job any easier. “It is a traumatic experience for us,” Gerrard says, “not for the rhino.”

Spioenkop Nature Reserve has fared unusually well in its fight against poaching. Out of 15,600 rhinos in South Africa, 1,175 were killed by poachers in 2014. In 2015, the country began dehorning rhinos to considerable success. By 2019, the number of dead rhinos had fallen to 594. By 2020, it was 394. Nevertheless, Gerrard defines a truly successful dehorning effort as “zero animals poached.”

Two big cats, two big trophies. DappleRose. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

It will be a hard goal to reach. After COVID-19 effectively shut down international travel, tourism revenue in Africa plummeted, leaving conservationists cash-strapped in their anti-poaching campaigns. Spioenkop Nature Reserve has struggled to patrol its vast territory, but the issue goes beyond just South Africa. Wildlife tourism generates $29 billion each year and employs 3.6 million workers across Africa. The lack of sufficient funds for anti-poaching efforts is a continent-wide problem.

In Zambia’s Kafue National Park, poaching takes place at the edges of the park, where patrols have been cut back. In 2020, the park reported a 170% increase in snares, which snag wild cats. That same year, two lions were killed while none had been slain the year before. More disconcerting, patrollers increasingly find poached animals gored for “buck meat.” Poor local villagers, desperate from COVID-19 lockdowns, have joined poachers in the hunt to earn a living and put food on the table.

By and large, however, poaching is the work of international crime syndicates working in the black market. Some conservationists advocate legalizing the sale of poached items such as rhino horns and ivory to lower the market value, reducing profits for poachers. In Kenya, courts have buffed up their prosecution efforts, leading to a precipitous drop in poaching. Dedicated legal teams actively pursue convictions for poaching, and those caught red-handed face long prison sentences and fines of up to $200,000. Still, the black market provides lucrative opportunities for locals willing to break the law in hopes of amassing a fortune. A 35-pound black rhino horn can be worth up to $2 million. For poor Africans, the opportunity is often irresistible.

Confiscated rhino horns. USFWS Headquarters. CC BY 2.0.

At Mpala, a research center in central Kenya, patrols have adopted a digital approach to combat rampant poaching. They use the SMART app (spatial monitoring and reporting tool) to track every animal a patrol encounters—alive or dead. It also allows them to track people seen infiltrating the parks. Conservationists are attempting to make up in brainpower what they lack in manpower; less tourism revenue led to slashed budgets, which meant fewer patrols. However, park managers agree that addressing the root cause of poaching, poverty, is the best solution to the problem. In this regard, nobody seems to have an answer.

So the traumatic work of sawing off rhino horns in Spioenkop continues. “We cannot let our guard down,” says Elise Serfontein of the organization Stop Rhino Poaching. “The kingpins and illicit markets are still out there, and even losing one rhino a day means that they are chipping away at what’s left of our national herd.” With one rhino’s horn sheared to a nub, the team moves on to the next. The rhino sleeps in the field as they approach. One member revs the chainsaw and begins cutting. White flakes flutter through the air like dust.

Michael McCarthy

Michael is an undergraduate student at Haverford College, dodging the pandemic by taking a gap year. He writes in a variety of genres, and his time in high school debate renders political writing an inevitable fascination. Writing at Catalyst and the Bi-Co News, a student-run newspaper, provides an outlet for this passion. In the future, he intends to keep writing in mediums both informative and creative.

A Closer Look at East Africa’s Human-Elephant Conflict

For farming communities in East Africa, elephants pose a danger to survival. Consuming up to 1,000 lbs of food a day, they destroy farmers crops in hours, cause injury and even death. While poaching is publicized, it is actually the human-animal conflict that poses the greatest threat to the species survival.

Read MoreRecycling for the Future: Scientists Create Enzyme Formula to Break Down Plastics

Our human habit of excessive plastic consumption has degraded the environment, and we have yet to find a solution to undo the damage. However, scientists have paved the way for a much speedier resolution with a new enzyme formula.

Scientists have crafted a formula of two plastic-munching enzymes, PETase and MHETase, to rapidly break down plastic waste. The PETase enzyme has been previously used to break down plastics, and now when combined with MHETase, this duo can dissolve plastics six times faster.

PETase, as its name implies, is the enzyme that dissolves polyethylene terephthalate (PET), a thermoplastic polymer commonly used in plastic bottles and clothing. The polymer PET takes hundreds of years to break down, but with PETase, the process is reduced to mere days.

However, the rate at which PET is produced has proven to be far too mighty for the rate at which PETase can break plastics down.

So far, researchers have only found a way to break down plastic bottles, which account for just over 4% of all of the PET production that exists. Ecologists find this minuscule number frightening, as many of Earth’s limited resources are being pushed to the brink while a shift to regular recycling has been quite limited. Scientists are also highly concerned with PET’s active role in accelerating climate change. The copious amounts of greenhouse gases that are spit into the atmosphere during PET production grows more concerning as PET usage rapidly increases. PET is a sturdy material that is not broken down well by microbial organisms, so other potential solutions have failed to effectively break down the impenetrable product. The downside to current popular methods of breaking down plastics is the high amount of energy required; in turn, this becomes an incredibly costly process.

Now, an innovative team consisting of American and British scientists has found a way to create a “super-enzyme.” The MHETase enzyme was studied using the Diamond Light Source, a powerful X-ray beam that is 10 billion times brighter than the sun, to study the atoms of MHETase. They have engineered a way to connect PETase with its sibling enzyme MHETase, which has now tripled the speed of the breakdown process. Their preliminary experiments tested the ability of the enzymes to work together, but as two separate enzymes. Then, they physically connected the two enzymes, and found that the two work better attached. This new enzyme deconstructs plastics in two steps. First, PETase eats away at the surface of the plastic. Then, MHETase slices up the rest.

Researchers are hoping that providing a commercially sustainable method for plastic deconstruction will shift people away from depleting Earth’s oil and gas resources. The discovery of the super-enzyme formula certainly holds hope for preserving the world’s ecology, if only humans learn to change destructive consuming habits for the better.

Ella Nguyen

is an undergraduate student at Vassar College pursuing a degree in Hispanic Studies. She wants to assist in the field of immigration law and hopes to utilize Spanish in her future projects. In her free time she enjoys cooking, writing poetry, and learning about cosmetics.

Zimbabwe’s Mining Ban: A Potential Empty Promise?

The government of Zimbabwe now bans mining in its national parks, but environmentalists argue that the prohibition is hardly adequate.

An elephant at a watering hole in Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park. BARMCD. CC BY-NC 2.0.

After mounting pressure from conservationists, Zimbabwe’s government has declared a mining ban in the country’s national parks. Reports have circulated that Chinese companies are scouting out coal mining sites in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe’s largest national reserve. The park stretches over nearly 6,000 square miles and is home to about 50,000 of Zimbabwe’s estimated 86,000 elephants. Extensive conservation projects are conducted in the region to preserve its plethora of wildlife species, but the call to protect the elephant population has drawn the most intense focus.

The government’s new ban is the result of a case brought to the country’s High Court by the Zimbabwe Environmental Lawyers Association. The group argues that mining would destabilize the park’s biodiversity while injuring the fragile ecotourism sector. This case was first brought to the High Court after officials of Afrochine Energy and Zimbabwe Zhongxin Coal Mining Group were arrested for conducting illegal mining projects only to be released with special permission by Zimbabwe’s President. Outrage immediately ensued, and conservationists rode the wave of anger to action.

The immense pressure on the government to implement change follows months of anger by environmentalists claiming that Chinese mining companies have already caused catastrophic damage in other regions of Zimbabwe. Environmentalists explain that the companies dump toxic waste, clogging precious dams and resulting in substantial drops in local wildlife populations. Locals also resent the presence of Chinese mining companies due to diminishing livestock populations and disrupted irrigation routes.

Environmental groups also argue that mining will perpetuate the drought and overcrowding problems that have already killed hundreds of elephants. Local residents deal with regular poaching disputes and rely heavily on income from ecotourism; so, many fear that failure to hold off Chinese mining companies could cause economic damage and increased levels of conflict. Furthermore, many Zimbabweans believe that mining in Hwange is only one piece of the bigger picture. Gold and diamond mining sites pepper other parts of the nation, causing equal degrees of environmental destruction to the over 1,000 species of animals that roam the country.

Tusks removed from a poached elephant. Sokwanele. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

For now, it seems that the government of Zimbabwe has yielded to the demands of conservation groups, but environmentalists appear far from satisfied. The government says that it is canceling current mining titles, but conservationists are doubtful that this is enough. Shamiso Mtisi, deputy director of the Zimbabwe Environmental Lawyers Association, states that the group is demanding an interdict, which is a legally binding prohibition. Pressure on the government to act quickly increased significantly in the past week as 11 young elephants died due to an unknown bacterial infection. Investigations are now proceeding to determine the cause of the elephants’ deaths, and whether poisoning may be linked to nearby mining activity.

Although the High Court’s verdict is already known, but whether or not Zimbabwe’s government will take the necessary steps to save the country’s natural and economic resources remains a mystery.

Ella Nguyen

is an undergraduate student at Vassar College pursuing a degree in Hispanic Studies. She wants to assist in the field of immigration law and hopes to utilize Spanish in her future projects. In her free time she enjoys cooking, writing poetry, and learning about cosmetics.

Mauritius Faces Ripple Effects From the Largest Oil Spill in its History

The recent oil spill in Mauritius threatens the island’s ecosystems and its people. More than 1,000 tons of oil spilled into the Indian Ocean, and the ocean’s biodiversity is at risk, fishing is no longer possible in contaminated areas and the local population has been hurt by pollution. Not to mention shattered tourism industry.

Read MoreRhino in South Africa’s Kruger National Park. Glen Carrie. Unsplash.

South Africa’s Success Continues in Slowing Rhino Poaching

Poaching, the illegal hunting and sometimes killing of animals, has always been a serious threat to conservation efforts. Animals like rhinos, elephants, tigers and lions are often the target of poachers looking to make money through exotic pet sales and traditional medicine practices. While habitat destruction does contribute most to the strain on many animal species, the illegal trading and selling of wildlife has gained popularity as e-commerce continues to grow.

Kruger National Park, South Africa. Vincent van Zalinge. Unsplash.

In South Africa, this illegal practice has finally decreased to the point where native rhino species can finally thrive. Rhinos are often hunted in South Africa because their horns are used for traditional medicine in Asia. In just the first six months of 2020, South African rhino poaching decreased by 53% - a goal that the South African Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries has been working toward for the past five years. Only 166 rhinos have been poached for their horns in the first six months of 2020. This is a significant drop when compared to the 316 rhinos that were poached in the first six months of 2019.

Street art against rhino poaching. Kosmoseleevike. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Barbara Creecy, South Africa’s minister of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries, said, “After a decade of implementing various strategies, and campaigning against ever-increasing rhino poaching by local poachers recruited and managed by crime syndicates, efforts are paying off. We have been able to arrest the escalation of rhino losses.” The ministry credits this success in part to COVID-19 lockdown measures as they kept poachers from actively hunting.

Additionally, the lockdown measures have made poachers much easier to spot. From January to June, 38 suspected rhino poachers have been arrested in Kruger National Park and 23 firearms have been confiscated. These arrests also led to historic convictions as the ministry reports that from January to June, the National Prosecuting Authority managed to obtain convictions in 15 cases marking a conviction rate of 100%. To guarantee that these poachers will not return to poaching, they were given lengthy sentences. Coordinated efforts with the South African Police Service, the Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation (also known as the “Hawks”) and the Department of Justice have curtailed the selling and purchasing of poached rhino horns.

South Africa’s success came just in time to celebrate World Ranger Day on July 31, a day dedicated to rangers who have lost their lives in the line of duty. The minister paid tribute to these brave men and women who have risked their health and safety, both by stopping poachers and risking possible exposure to COVID-19. “Our rangers have remained at the forefront of the battle against poaching, despite the national lockdown, contributing to the decrease in poaching. In this time, rangers have had to face not only the threats posed by poachers, but they, and their families, have also had to deal with the danger of contracting COVID-19,” said the minister. It is apparent that their bravery has paid off as the rhino population of South Africa is now at a decreased risk of population decline.

Renee Richardson

Renee is currently an English student at The University of Georgia. She lives in Ellijay, Georgia, a small mountain town in the middle of Appalachia. A passionate writer, she is inspired often by her hikes along the Appalachian trail and her efforts to fight for equality across all spectrums. She hopes to further her passion as a writer into a flourishing career that positively impacts others.

Harajuku, Japan. SkandyQC. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Why Fertility Rates Could Halve by 2100

The global population growth rate is predicted to take a drastic downward turn, with experts believing that major countries such as Japan and Italy will see their populations halve by 2100. This is an unprecedented problem that could negatively impact society as a whole if the trend continues. The necessity for the world to plan and prepare for this outcome has become increasingly clear as global trends solidify.

Why the Sudden ‘Baby Bust’?

In the 1950s, women were having an average of about 4.7 children in their life span. In today’s world, women are instead averaging 2.4. The causes for this turnaround include increased educational opportunities, greater numbers of women in the workforce and increased access to contraceptives. There seems to have been an attitude change toward parenthood in recent years. In more developed countries, the roles of women have turned in favor of being outside the home, leaving less time for children. This contrasts starkly with historical norms, where women stayed home to take care of the family and house while men left to go to work.

What Are the Global Consequences?

While an initial evaluation might suggest that a smaller population would be better for the environment, professor Christopher Murray of the University of Washington suggests that this would lead to an “inverted social structure” where there are more older people than young. This raises questions about who will pay taxes and take care of the elderly. These are issues that the younger generations will have to worry about as they reach adulthood. “We’ll have to reorganize societies,” Murray says, in order to make current population trends sustainable.

The world’s changing population numbers could lead to a shift in the world’s dominant powers. For example, India is set to replace China as the world’s most populous country as China faces a population decline as soon as 2024. By 2100, India’s population would be followed by Nigeria’s, China’s and the United States’.

Why Nigeria?

As COVID-19 and other health challenges ravage developing countries, access to contraceptives and other family planning becomes limited. This leads to more pregnancies in places such as sub-Saharan Africa, which is set to “treble in size.” Africa’s forecast for rapid growth calls attention to the current social situation regarding racism, with Murray stating that “global recognition of the challenges around racism are going to be all the more critical if there are large numbers of people of African descent in many countries.”

This shift in global power is expected to create issues surrounding development, social status and racism. Especially in the current social environment, racism could become one of the largest issues if these predictions prove to be true.

What is Being Done to Prevent Population Decline?

Countries such as the United Kingdom have incentivized and increased migration. However, this is only a temporary fix as most countries begin to drop in population. Other countries have increased paid maternity and paternity leave, but have still seen few shifts toward larger families. Sweden has managed to “drag its rate from 1.7 to 1.9” while Singapore still has a rate of 1.3. Women simply cannot be expected to increase the number of children they have due to policy changes, and current trends show that this attempt will not be enough.

If the global reproductive rate drops to the predicted 1.7 by 2100, population extinction could become more of a legitimate concern. The 2.1 threshold, which is necessary to sustain the world’s current population, is instead being used as a target for future growth. Ultimately, though, young adults need to start planning for a future where society’s age makeup is inverted.

Elizabeth Misnick

is a Professional Writing and Rhetoric major at Baylor University. She grew up in a military family and lived in Europe for almost half her life, traveling and living in different countries. She hopes to continue writing professionally throughout her career and publish her writing in the future.

Plastic Rain: The New Acid Rain

The world produces approximately 359 million metric tons of plastic every year, half of which is single-use and immediately thrown out. A 2017 study discovered that of the 8.3 billion metric tons of plastics produced, 12% is incinerated and only 9% is recycled. The remaining 79% accumulates in landfills and the natural environment, including the oceans. More than 8 million tons of plastic makes its way to our oceans every year, polluting an already fragile environment due to habitat elimination, destructive fishing practices and other pollutants such as oil spills and reactive nitrogen and phosphorus that rivers like the Mississippi carry into the ocean.

Some of those pollutants enter the water cycle in the form of acid rain. Acid rain poisons everything it comes into contact with—the sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides harm humans, wildlife and the Earth. Acid rain was first discovered in the U.S. “in the 1950s when Midwest coal plants spewed sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides into the air, turning clouds—and rainfall—acidic,” according to the National Science Foundation. It wasn’t until widespread damaging effects began on forests and bodies of water in the Northeast that Congress took action by passing the Clean Air Act in 1970, which imposed emission regulations to target air pollutants. This was not enough, however, as acid rain became one of the most well-known pollutants during the 1970s and 1980s as it damaged German, Czech and Polish forests in the “black triangle” region and increased the acidity of bodies of water in the U.S., particularly along the Atlantic coast, which in turn harmed the aquatic organisms and ecosystem.

Acid rain may be slightly less of a problem now with effective environmental regulations, but our environment is not any less at risk. There is a new threat to our environment that is falling along with rainwater: microplastics.

A study conducted in 2019 by researchers at U.S. Geological Survey shows that microplastics have made their way into the water cycle and are permeating virtually every surface on Earth with no way to control where the plastic rains down. Researchers discovered that over 90% of the water samples taken along Colorado’s Front Range contained microplastics.

Microplastics are plastic debris that are less than 5 millimeters in length that come from a variety of sources, including microbeads—exfoliants used in skin products and toothpastes— textile fabrics, and larger plastic items that have degraded into smaller pieces after being broken down by wind, the sun and waves. In addition to taking a long time to decompose, microbeads are damaging due to their ability to absorb toxins and are notoriously difficult to remove from the environment due to their minute size. They became such a problem that Congress passed the Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015, which prohibits the manufacturing of rinse-off cosmetic products containing microbeads. Although there is not enough research at this point to determine how detrimental microplastics are, it is evident that they are polluting the Earth—appearing in remote areas such as the French Pyrenees and even hitching rides on sea breezes.

New research published last month indicates that plastic rain is a huge problem—leaving no place safe from plastic pollution. Researchers collected rainwater and air samples from 11 protected areas in the western U.S. for 14 months and discovered over 1,000 metric tons of microplastic pieces in the rainwater collected, which is “the equivalent of over 120 million plastic water bottles,” according to Wired. The researchers predicted that in just five years 11 billion metric tons of plastic are projected to accumulate in our environment, which is equivalent to the weight of approximately 55 million blue whales.

Asiya Haouchine

is an Algerian-American writer who graduated from the University of Connecticut in May 2016, earning a BA in journalism and English. She was an editorial intern and contributing writer for Warscapes magazine and the online/blog editor for Long River Review. She is currently studying for her Master’s in Library and Information Science. @AsiyaHaou