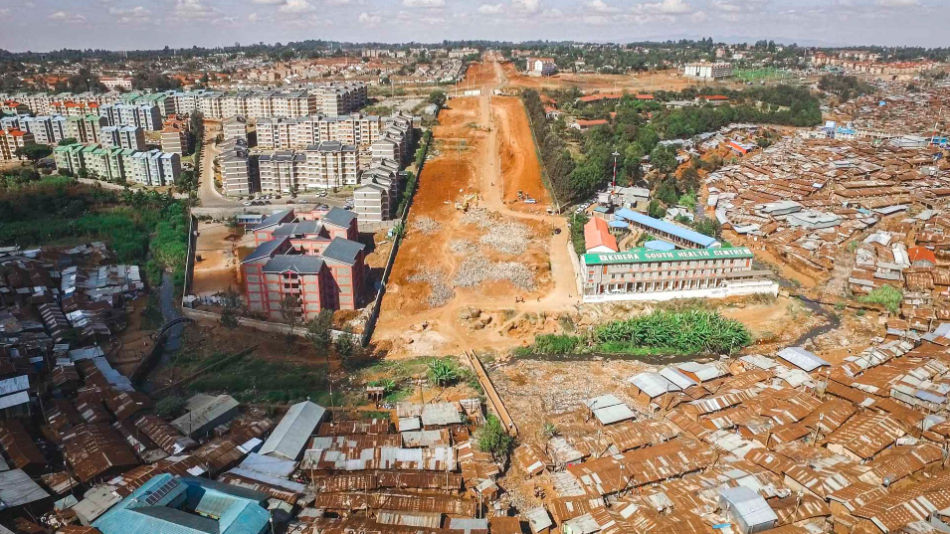

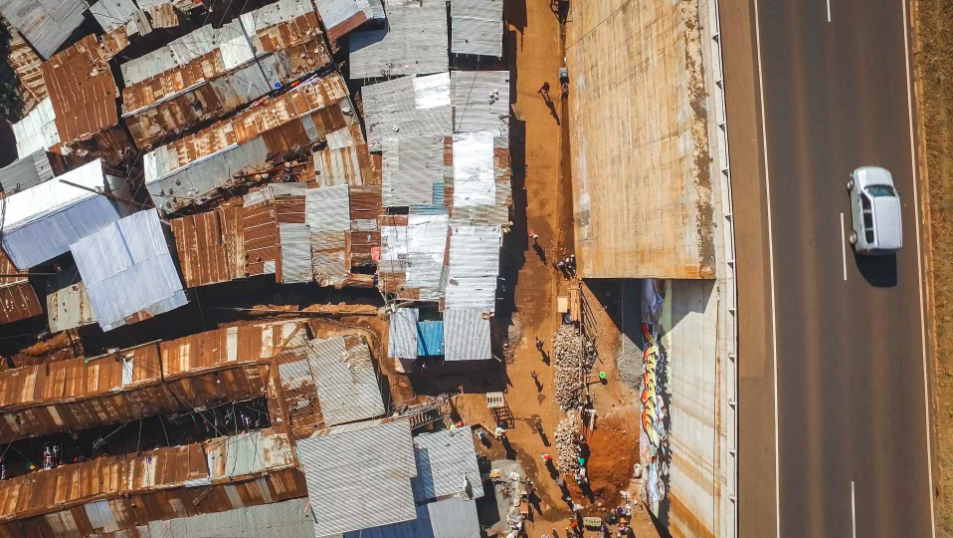

South African apartheid is frequently written off as a memory, something that ended decades ago. But from the start of my visit to South Africa, it became clear that the violence of that period has continued to bleed into the present, manifesting itself in clear racial and economic divides.

I visited Cape Town in the summer of 2016. Cape Town is a city of contrasts—tall, imposing mountains cast shadows over clear blue seas, and seaside villas luxuriate only a few miles away from derelict townships.

These townships are the subject of this piece. Townships in South Africa are villages that remain from apartheid-era forced exoduses of non-white people, cast out of their homes and crammed into segregated areas.

These townships still stand today. They are mostly collections of mottled tin-roof shacks and cramped streets, and they are home to 38% of South Africa’s population of 18.7 million.

From the beginning of my arrival in South Africa, I was told by locals that the townships were unsafe, especially for outsiders. But one day, I returned to my flat in the town of Observatory and one of my roommates asked me if I wanted to visit one.

The visit would be hosted, she told me, by Dine With Khayelitsha, a program founded by four young township residents designed to foster communication between their communities and those outside. Dine With Khayelitsha started in March 2015, as part of a partnership with Denmark and Switerland intended on working as a fundraiser. It then grew and has now hosted over 100 dinners. Each dinner is attended by at least one of the founders, who assures the safe transportation of every participant.

Thanks to this organization, I found myself on a bus driving into one of the townships, and then I was suddenly in a house with a bunch of strangers, eating authentic South African beans and meat.

We arrived at the township’s president’s home, though she was not there—she was outside campaigning, and instead several locals were cooking the meal for the night.

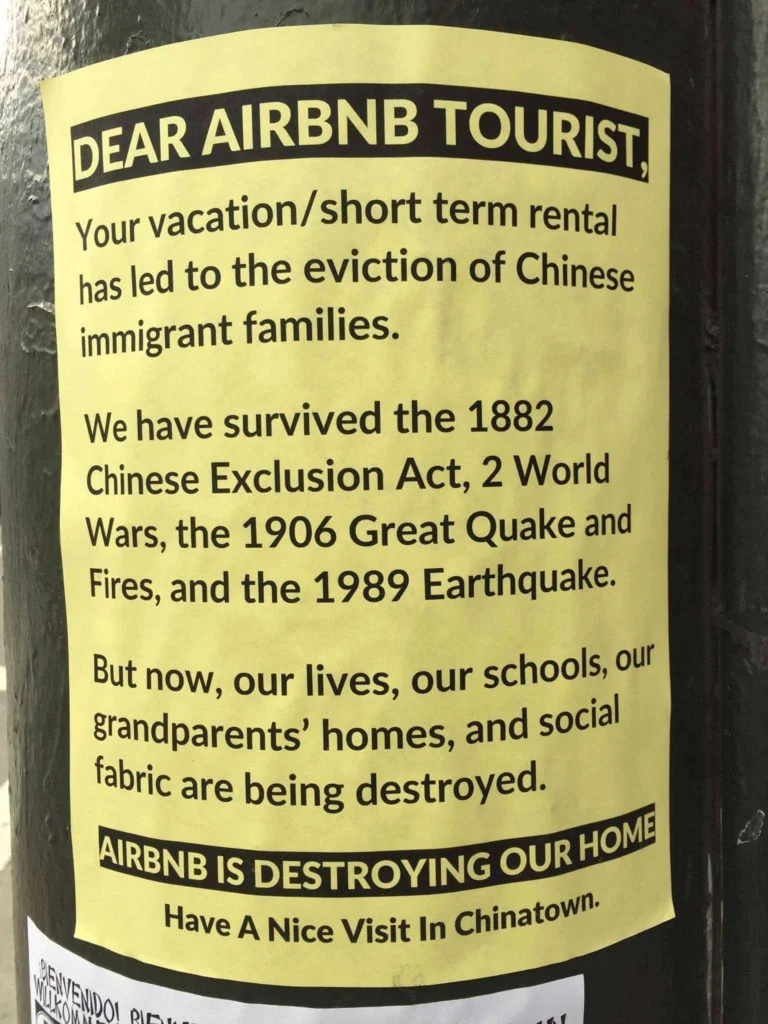

I had come with my new friend, and among the other attendees were two Dutch women, an artist from Germany, a couple from France and Morocco, and a South African black woman. Noticeably absent were white native South Africans, a fact that we asked the hosts about. Apparently, South Africans themselves still persistently ostracize the townships, creating divisions between themselves and the poorer underside of their country.

Our hosts were a few young men from the townships. They had all attended college and one worked in IT and another in software engineering, and most of them also ran after school programs such as leadership and self-esteem workshops for township kids. They had started this organization in an effort to generate more dialogue among South Africans and to raise awareness and reduce stigma concerning the townships.

First, they asked us to discuss one act of kindness we’d performed recently. As night fell, the talk began to flow more easily. We discussed the fact that so many kids from townships are forced to go through school and university, if they can make it that far, in order to get menial jobs that can support their families. For these kids, following their dreams is not an option, but it is rather an inconceivable luxury. One of the hosts said that he would love to run education programs for kids, but instead he had to become an engineer to support his family.

After dinner, as we were waiting for a bus to come pick us up, I asked one of the men if most people born into townships grow up wanting to escape, to find better lives. He told me that some did, but in his opinion, it is far more important to stay in the townships and to try to create a better life there. That’s what he had done; he’d gotten an education and a job and still lives in the townships, trying to create programs and to help uplift the state of the community.

I talked to another local who was a writer, and his eyes shone as he talked about how he can capture strange and vivid moments with words—and another who spoke passionately about his desire to hear stories from people all around the world. There was an undercurrent of kindness that seemed to link these people together that I have rarely seen; a desire to include others, to tell stories and to share parts of their lives, to not build walls but to rather create open streams of connection. To create rather than to destroy.

Conversations like this one cannot heal or make up for old wounds inflicted upon non-white people in South Africa—only physical reparations and policy changes can truly begin that process. But they are a step in the right direction—a step towards understanding that we are all part of the same global community, and the walls between us are really made of dust.

EDEN ARIELLE GORDON is a writer, musician, and avid traveler. She attends Barnard College in New York.