I’ve been trying to find a way to write this since I’ve gotten back to the United States with a single backpack and next to no money. For the four months that I was away, the United States of America seemed to unravel in a way that I hadn’t seen before and my bones felt so excited, so prepared to come back.

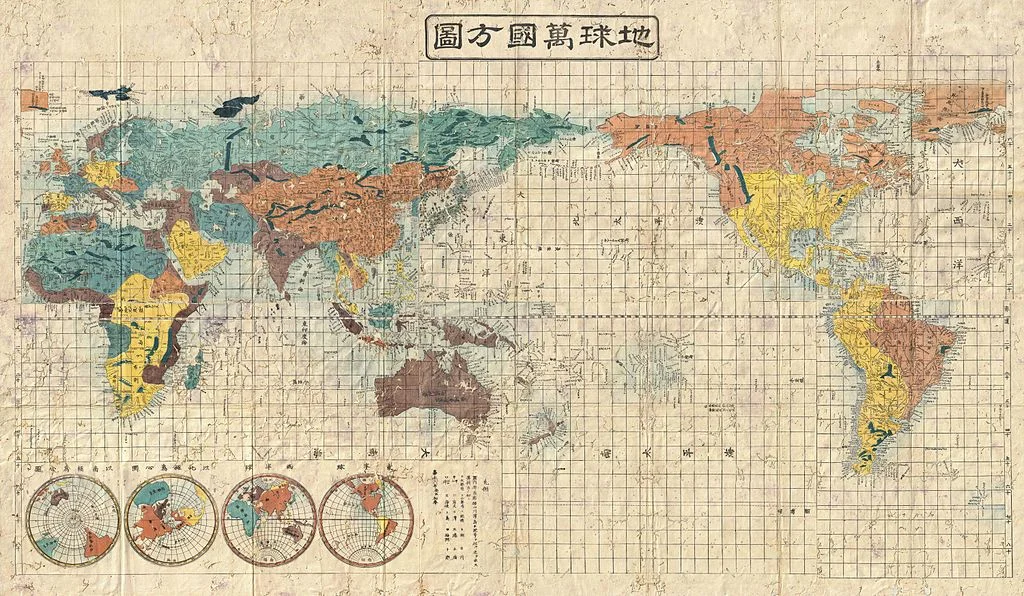

Starting in December 2016, I traveled throughout the Philippines for three months and spent another month in South Korea. This trip was integral, influential in so many ways to me. I dove headfirst into a new region of the world that I’d previously not given much thought to and I can still recall sitting in this bedroom only a week or two before that trip began and thinking, “What am I getting myself into?” as I researched the ins and outs of some of the things that I might experience.

Sometimes I feel that there is a switch in black people specifically. We tread through the world as flawlessly or strongly as possible. We climb ladders, break glass ceilings, win athletic events, and do so in the name of a lineage that has been stripped away from us. The black experience in the United States is so unique and tortured and real in ways that is still hard to express to people who haven’t been born into it or have spent their entire lives trying to contextualize it.

I believe this switch in each black person is a way to protect us, push us forward, and allow us to navigate spaces that we are not always readily welcomed into. As I traveled through the Philippines more specifically, this switch was turned on all the time. From the very first days of stepping off the plane and meeting people of different backgrounds and classes and political ideas, I was faced with a wave of self protection that was layered into how I interacted with anyone that I met.

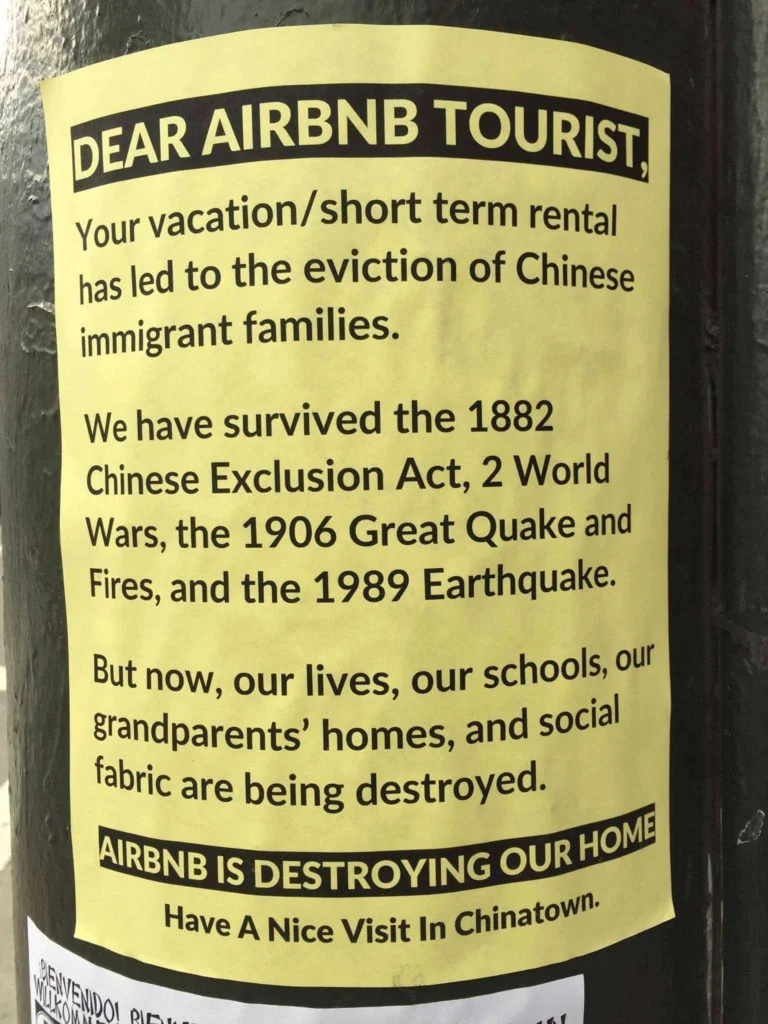

Kids would follow me in the streets and point. Some people would ask to take photos. Others would ask questions about my dreadlocks. One time in Chinatown, my friend exclaimed behind me, “Wow, a black person!” because as he walked behind me in the crowded city streets of Manila, it became so obvious that people just didn’t stare as I walked by. They gawked. Kids sometimes called me the N-word because it was probably what they’d seen black people call each other in rap videos or movies.

“Wassup my brother?” was also a common thing for kids to say to me.

I had moments where I had to explain the basics of anti-blackness in the United States to some Filipinos. One time a woman told me that my hair looked crazy. One night I was lost while trying to meet friends and at a club. Filipino cops stopped me and asked if I needed help. During their gracious car ride, they asked me if it was true that black men had bigger penises.

Layer all of this with the fact that I am queer and understand that much of the world has a complicated relationship/ideal of acceptance towards the LGBT community; you can begin to guess why this guardedness was a part of how I interacted with people.

As a black person, I have learned to demand presence in so many spaces that I step into. As an activist, I try to be intersectional and aware of the political context of spaces that I enter. I could never go wholeheartedly into another country as an American and expect everyone to be educated on the nuances of life as queer, black male in the United States. Culture is deep and can be changed in an instant or over the course of decades, centuries.

But with this deep need to understand things as they come, feelings often get muddled. In South Korea and the Philippines, I would let people touch my hair, something that’s sort of an unspoken violation of respecting black folks and their bodies. At the time, I chalked it up to exhaustion, a lack of willingness to fight for respect for my racial experience at all times. Now that I am faced with the prospect of wondering if I should go back to the region of SE Asia for another trip, I am finally able to realize the whopping truth of what I often felt.

Humiliation

I felt humiliated and tried to stuff it inside of myself, wake up every day and face the adventure of being a backpacking entrepreneur on the other side of the world, something that is a privilege of it’s own. But the truth was that I’d drained my bank account to be there. I constantly thought,

“Why the fuck did I travel across the world to deal with this racist bullshit?”

Most of the time I was too afraid to express these feelings to Filipino people, almost in the same web of anxiety that I used to have when censoring myself when around white folks here in the States. In fall of 2016, I helped organize a memorial for Ty’re King, a 13 year old boy shot and killed by Columbus Police. At the memorial, a white guy came over and expressed his condolences. Then he compared the 13 year old boy to Osama Bin Laden and tried to spew his white privilege and fragility all over a space meant to show respect for black pain and this boy’s life.

I remember being angry, telling the guy to get the fuck away from me and how hot and immediate my body felt. So much of the past three years to me has been trying to dig into the power that allows myself to believe, “It’s okay to be angry. It’s okay to admit that you were humiliated. It’s okay to pop off.”

As black folks, we are so often used to being told that we hold the weight of our entire community on our backs. This is a reinforced ideal, that for black folks, is so different than the language around other racial groups. If you are black, how many times have you heard the following?

Don’t be hanging with those white folks and thinking you can do all the things that they do.

You gotta work twice as hard to get half of what they do.

Those white folks will be watching you.

I took care of you so you could hopefully take care of me and your father one day.

All of these are signifiers of the complicated bridge that weaves the black experience. We want to be seen and heard, but when we are denied representation, we claw our way into spaces and tell ourselves that we are “unapologetically black”.

Issa Rae, the creator of the show Insecure, recently said, “So much of the media presents blackness as fierce and flawless. I’m not.” This statement immediately made sense to me because the Strong Black Woman stereotype has been around for a reason. Self care is discussed, but how do we exercise it? Why are black people often left with the burden of contextualizing how racism and stereotypes continue to exist and hurt us? Why do we believe that we have to be so damn strong, so damn resilient all the time? What would break if we let the dam loose, let the world know how we really feel?

Is it because if we are afraid that the world would aim to destroy us once more if we were honest?

The answer could be in afro-pessimism and what Frank B. Wilderson III describes in an interview:

Normally people are not radical, normally people are not moving against the system: normally people are just trying to live, to have a bit of romance and to feed their kids. And what people want is to be recognized, to be incorporated. And when we understand that recognition and incorporation are generically anti-Black, then we don’t typically pick up the gun and move against the system, even though that’s impossible. And I think that our language is symptomatic of that when we say that ‘I don’t like police brutality’. Because, here we are saying to the world, to our so-called ‘people of color allies’ and to the white progressives, ‘we’re not going to bring all the Black problems down on you today. If you could just help us with this little thing, I won’t tell you about the whole deal that is going on with us.’

*

What freaks them out about an analysis of anti-Blackness is that this applies to the category of the Human, which means that they have to be destroyed regardless of their performance, or of their morality, and that they occupy a place of power that is completely unethical, regardless of what they do. And they’re not going to do that. Because what are they trying to do? They’re trying to build a better world. What are we trying to do? We’re trying to destroy the world. Two irreconcilable projects.

Maybe self care starts with recognizing the disappointment I felt every time in the Philippines when I’d be informed that I was “the first black person” to frequent a particular business or area of the country. Not only was my mind mangled by trying to contextualize all of the racist/stereotyping attempts by people I’d met trying to get to know me, but I was also faced with the fact that, once again, I was one of few to explore in certain ways.

So I’ll say it again. I felt humiliated and as I sit here, I find it hard to come up with many reasons to go back for the foreseeable future. When I admit this, a deeper anxiety slips in that I refuse to really indulge. This anxiety says, “Well, if you’re a traveler and you’re black, does this mean you’ll never really find a home in the world? A place that gets what it’s like to be you?”

As for the answer to this question, I don’t know, but the hopeful part of me says that I need to keep searching on my own terms before I allow my already short life of 23 years to be marred by a belief that the world is wholly inaccessible to me, a black person that wants a world where different identities are respected, but never vital to someone’s value.

If I wanted to put these horrible realizations to deeper use, I would ask myself the question, “Well, what would I feel if I just went back? And got over it?”

Maybe I’d be attempting to actualize a stronger version of myself that can deal with being stared at all the time, asked if I play basketball and told I should put my sexuality (which is fetishized by white supremacy) to good use. That version of myself, I don’t think I would like very much. That version of myself would lessen the vulnerability that I feel is so integral to creating compelling art and embodying the kind of blackness that acknowledges the strength of who we are/what we are capable of while not stripping myself of the ability to feel pain, anxiety, anguish, and humiliation.

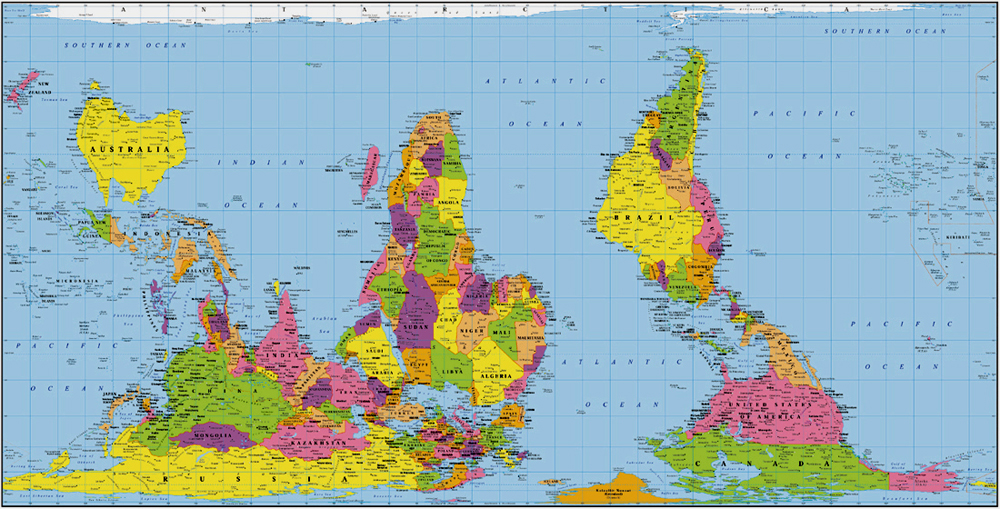

This vulnerable version of myself is what I believe is the ideal reality to struggle towards. One where walls and borders and barriers that are physical become as obsolete as the one in our minds, but maybe that reality is only possible with people like me (and hopefully you), who face the turmoil as it comes and uses it as a way to inform how we go into the world next time around.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON FUTURE TRAVEL.

PRINCE SHAKUR

Pro-black, feminist, lover of locs and queer with restless feet.

![[Name withheld] - 20](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/638a651ad5f9324e20972bf2/1670014524351-36X8BO8GD9MSYFTOO5G8/11+syria11youngmen-11aleppo-syria-matador-seo-940x624.jpg)