A new law in Oregon decriminalized possession of small quantities of hard drugs. With Washington state possibly following its lead, the war on drugs might begin to be phased out.

Is the end in sight for the war on drugs? Thomas Martinsen. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

Currently, an Oregon police officer cannot arrest someone for possession of small amounts of heroin, meth, LSD or any other hard drug. Ballot Measure 110, voted into law last November, decriminalized the possession of small quantities of such substances. Instead of a felony conviction and jail time, a drug user caught red-handed will face either a $100 fine or a medical evaluation that could direct them to an Addiction Recovery Center (ARC). The new law fundamentally changes the state’s approach to epidemic rates of drug use and could revolutionize the role of Oregon’s police force.

At its core, Ballot Measure 110 diverts drug users away from the criminal justice system and toward the health care system. The bill requires that a network of 15 ARCs be built to treat drug users and pair them with case workers who can help them reach sobriety. Funding for the ARCs will come, ironically, from tax revenue from legal marijuana sales. Oregon can expect a lot of money from such sales. In 2020, tax revenue from marijuana reached $133 million, a 30% increase from the previous year. Additionally, the state anticipates that more funds will appear as police stop pursuing arrests for drug possession.

The simple demotion of drug possession from a felony to a misdemeanor will have lasting repercussions. Before, an Oregon police officer who saw a pipe in a car could justify searching the car for illegal substances, since the pipe was proof of a possible felony. Now that it would indicate only a misdemeanor, the officer cannot search the vehicle. Arrests will decrease sharply as a result. The Oregon Criminal Justice Commission estimates that there will be 3,679 fewer arrests for possession per year, a 90.7% decrease. Distributors will still face criminal sentences since they possess drugs in large quantities, but users will receive health care, not jail time.

A disease, not a crime. Drugs Treatment Clinic Parus. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Building 15 ARCs by Oct. 1 will be a substantial challenge. Oregon will need to transition from addiction recovery programs focused on prisons to separate health care facilities that require supplies, staff and resources. Already, officers have made fewer arrests for possession to mitigate the risk of COVID-19 outbreaks in prisons. Thousands of drug users who would have landed in jails will now be placed into ARCs. Many who argued against the ballot measure now question whether so many facilities can be built by October.

They have other qualms, too. As crude as the criminal justice system can be, drug addicts who served time in prison often entered court-mandated treatment programs; this won’t happen now that drug possession is a misdemeanor. County sheriffs expressed concern at a potential surge in illegal drug use now that prison is not a deterrent. Since the ballot measure passed with 58.5% of the vote, it’s clear these arguments weren’t entirely persuasive.

The least worst option? Michael Kappel. CC BY-NC 2.0.

For one, prison might be the worst place to overcome a drug dependency. An addict is thrust into an unfamiliar environment to undergo withdrawal, and they may cope with trauma by self-medicating when the opportunity arises. The risk for opioid overdose alone is 129 times higher than average in the first two weeks after being released from jail. As for a potential surge in drug use, multiple examples of decriminalization in other countries indicate that this will most likely not occur. After decriminalizing hard drugs in Portugal, rates of drug use remained steady, but drug deaths fell as the percentage of users treated for addiction rose 21% between 2001 and 2008.

Criticisms of Ballot Measure 110 go beyond the issue of how to treat epidemic rates of drug addiction. They speak to a concern about the ability of Oregon’s health care infrastructure to manage the flow of drug users from prisons to ARCs. This transition plays into a more ambitious, long-term agenda that many advocates of Ballot Measure 110 advocate for: defunding the police. By turning criminals into patients, ARCs would take the issue of drug addiction and mental health crises away from police; Oregon is even considering an alternative to 911 that people can call for drug-related issues or mental health crises.

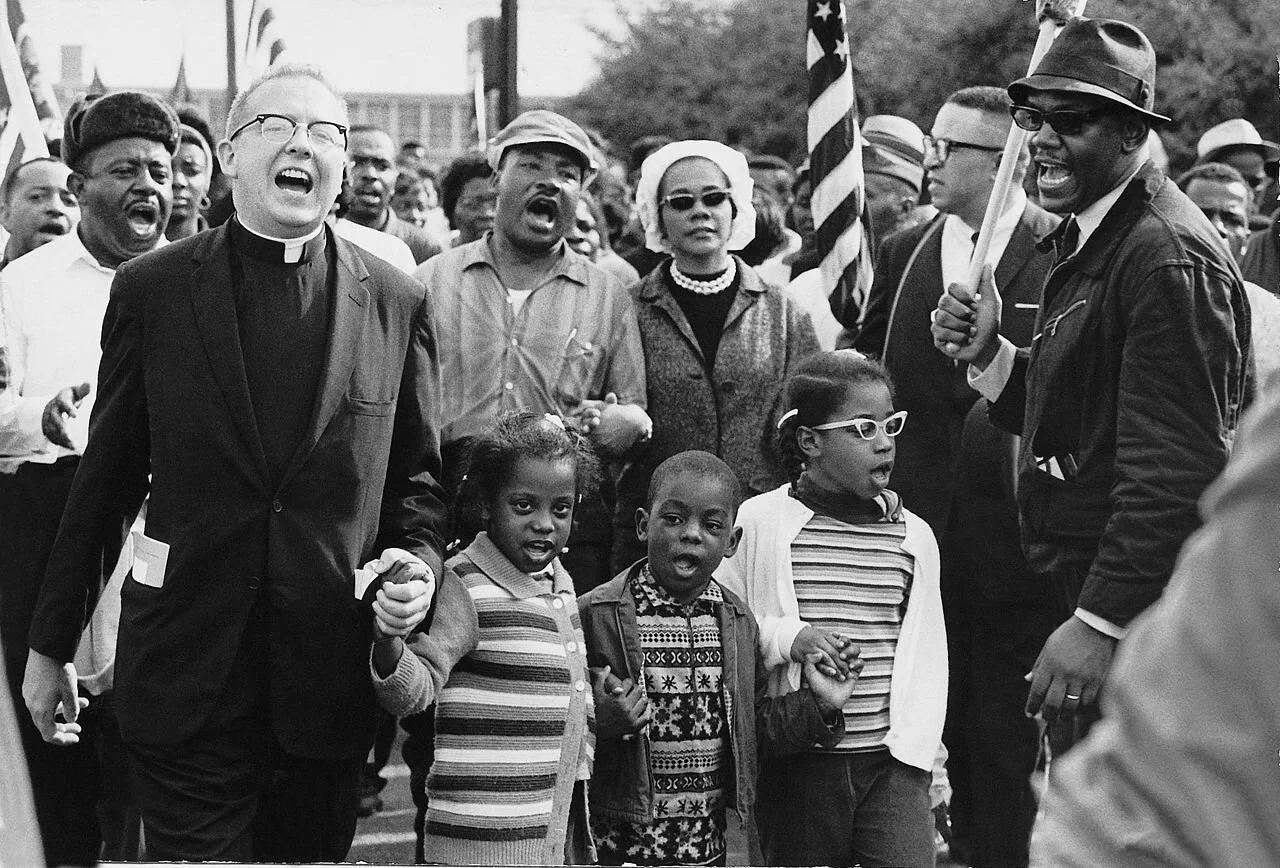

A Black Lives Matter protest in Portland, Oregon. Matthew Roth. CC BY-NC 2.0.

Washington state is considering a similar transition with House Bill 1499, which if passed would decriminalize drugs much the same way as Oregon’s Ballot Measure 110. Revenue for Washington state’s ARCs would come not from marijuA Black Lives Matter protest in Portland, Oregon. Matthew Roth. CC BY-NC 2.0.ana sales but from taxes on pharmaceutical companies, which played a large role in starting the opioid epidemic. Washington state currently has a program designed to lead drug addicts away from the criminal justice system and into treatment centers, the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) program. It differs from other diversion programs in that it provides care before, not after, an arrest and takes referrals from community members, not just law enforcement. Nationwide, the program has been held up as a model diversion program.

Both states will struggle to make a seamless transition from prisoners to patients. It requires reforming two systems that often become embroiled in partisan conflicts. When the Seattle City Council cut its police department’s budget by 11%, in part to fund diversion programs, 186 police officers quit in response. Oregon will labor to build 15 ARCs by October, even with abundant funding from marijuana sales. Despite the state’s efforts, success depends largely on ever-shifting political winds.

Michael McCarthy

Michael is an undergraduate student at Haverford College, dodging the pandemic by taking a gap year. He writes in a variety of genres, and his time in high school debate renders political writing an inevitable fascination. Writing at Catalyst and the Bi-Co News, a student-run newspaper, provides an outlet for this passion. In the future, he intends to keep writing in mediums both informative and creative.